|

|

|

| more images |

Sleeve Notes

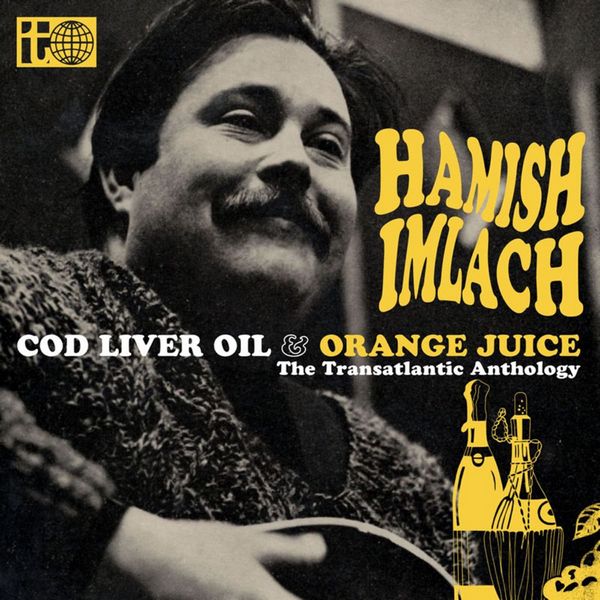

In many instances, it seems, the public is only able to assimilate one particular facet of a performer's talents. Away from the cognoscenti and the converted. Hamish Imlach's reputation in the wider world doesn't seem to extend beyond the stereotype of an obese but relentlessly cheerful Scottish club folkie.

Given that he chose to subtitle his autobiography Reminiscences of a Fat Folk Singer, clearly he wasn't that uncomfortable with such a caricature. And yet it does him a disservice: Imlach was far from being a one-dimensional talent. His resolute good humour and twenty-stone frame camouflaged a man and musician of impressively diverse talents, a folk enabler who was to fuel the careers of an entire phalanx of Celtic performers, including such notable names as Bert Jansch, John Martyn. Christy Moore and Billy Connolly A folk/blues guitarist of considerable finesse, he was capable of handling pretty much anything — tender love song, political statement, traditional ballad, comic monologue, drinking song, American blues standard — and customising it to the extent that, irrespective of the writer, it felt like an Imlach song. This collection of highlights from Hamish's lengthy sojourn with leading folk label Transatlantic attempts to shine the spotlight on all aspects of his work — including various rarities (such as a sitar-based version of 'Twa Corbies', unavailable since its inclusion on an exceptionally obscure 1967 live EP) and, of course, such trademark material as his de facto signature tune, Cod Liver Oil And Orange Juice'.

Despite being rightly regarded as one of the key players on the Scottish folk scene, Hamish Imlach was actually born (on 10 January 1940) in Calcutta. He was initially raised in Darjeeling until 1948, when his family moved to Brisbane, Australia. When he was thirteen years old, his parents returned to their native Scotland. In Glasgow, young Hamish attended the same school as Ray and Archie Fisher, who introduced him to the joys of folk music. His interest accelerated in 1958, when visiting American folklorist Ralph Rinzler showed him the finger picking guitar technique, and, by the following year, he was playing the opening night of the Glasgow Folk Club, held at the Corner House Cafe. With likeminded souls such as Archie Fisher and Ewan McVicar, he went on to run the club.

Around this time he also formed a loose partnership with Josh Macrae and Bobby Campbell (another schoolboy pal) as the Emmettones who were offered a deal by the Decca/Beltona label on the proviso that they sang Irish rebel songs. Three singles duly emerged, including the massive Irish hit 'Bold Robert Emmett', after Imlach and his cohorts were made the proverbial offer they couldn't refuse. Described in publicity handouts as 'three young lads from Donegal", the Emmettones were purely an ad hoc ensemble, though some years later they did tread the boards after Imlach was offered £50 for a single performance in the Gorbals. Intriguingly, their sole public appearance saw Imlach and Macrae perform as a four-piece with Archie Fisher and, on fiddle, the Incredible String Band's Robin Williamson.

The ISB were to have their murky genesis at Clive's Incredible Folk Club. Scotland's first all-nighter folk den. Imlach was a resident performer at Clive's, while also playing on a regular basis at the Glasgow Folk Centre and pub venues like the Clutha and the Scotia. By this juncture, he was firmly installed alongside the likes of Alex Campbell as one of the leading figures on the Scottish wing of the British folk revival. His guitar technique impacted on many young Turks, including Bert Jansch. who, while barely in his teens, chanced upon Imlach playing at the Howff club, opposite St. Giles in Ainslie Park. "Hamish Imlach was the first person I ever saw play a guitar for real". Jansch would recall. "That was it. Nothing else mattered."

He was also a major influence on budding singer/songwriter John Martyn. who carried Hamish's guitar to gigs in exchange for lessons. Still only sixteen years old, Martyn performed in public for the first time as support to Imlach. who encouraged him to combine traditional and contemporary influences and draw from a melting pot of folk, blues, country and ragtime styles "Hamish was a mine of information on these things, and simultaneously introduced me to socialism, because that was the driving force at the time", Martyn later reminisced "Folk music was 'folk' music, it was for the people, and quite deliberately so. He had a great attitude, and I liked his guitar playing. I learnt to play from him."

It was at establishments like Clive's and the Howff that Hamish honed his pioneering role of folk comedian. That initially unique persona of club singer, musician, bon vivant and raconteur paved the way for many other individuals, particularly a local banjo player by the name of Billy Connolly. Indeed, early Imlach performances like 'Whiskey. You're The Devil' and Street Songs were such a palpable influence on the embryonic Big Yin that Connolly would later be facetiously referred to in some quarters as "the world's No. 1 Hamish Imlach tribute act".

Across 1963/64 Hamish had appeared on both volumes of Decca's Edinburgh Folk Festival albums, the sleeve notes of Volume Two describing him as "rather like Burl Ives in appearance, but more rugged in voice". Both albums were produced by a freelancing Nathan Joseph, who also ran his own label, Transatlantic Impressed by the depth of talent in the Scottish folk club scene. Joseph signed Hamish and many other leading figures — Bert Jansch (though he'd already relocated to London by that point). Alex Campbell. Matt McGinn. Josh Macrae. Archie Fisher, Watt Nicoll and, a year or two later, the Billy Connolly-fronted Humblebums — to Transatlantic.

It was to be the start of a highly productive relationship. Between 1966 and 1973, Imlach would release no fewer than eight albums through Transatlantic and their ethnic imprint, Xtra (and that excludes myriad compilation LPs and appearances on various label samplers), as well as making one or two stand-alone singles and EPs. Despite the singer/songwriter conceit that was prevalent during the period. Hamish didn't really subscribe to the concept of 'artistic development, and his first album, a self-titled set that appeared in 1966. was probably his definitive release, containing much of his most-loved material and alerting the wider world to what would prove to be his abiding interests and passions.

One of the album's outstanding tracks was If It Wasn't For The Unions', penned by Hamish's great friend. Matt McGinn. "The press seems to blame all of our economic woes on the trade unions". Imlach was later to observe "Matt wrote this song about 1964. . . it's an Irish tune, often sung to words which end. Come and join the British Army'. This song reminds us of the debt we owe the unions … "

The likes of If It Wasn't For The Unions' and his adaptation of Scottish poet and songwriter Hamish Henderson's Men Of Knoydart' (a wonderful diatribe against English landowners) indicated that, notwithstanding his scabrous good humour and hail-fellow-well-met disposition. Imlach clearly had strong political beliefs. Even though he would claim that "I have friends who regard me as a wishy-washy liberal", he was included on the Economic League's blacklist of alleged Communist agitators — a situation that would plague Imlach for the rest of his days. During a 1989 House of Commons Hansard debate concerning the blacklisting of potential employees for their political sympathies, Hamish's case was raised as "a well-known folk singer in the west of Scotland" who was an "alleged Communist party supporter. When asked by World In Action why he thought he had been blacklisted and listed as a Communist party supporter, he replied. 'During my performances. I do have a go at Mrs. Thatcher and the Conservative Government.'" As the speaker. Maria Fyfe — the Scottish Labour MP for Glasgow Maryhill — wryly observed, at that rate millions of us can expect to be on the blacklist, and if not, ask ourselves why not!

But Imlach also had a fondness for traditional balladry, as revealed by the Child Ballad Johnny O'Breadislee' and the lovely Black Is The Colour'. The latter song had been popularised back in the 1940s by the American singer John Jacob Niles, but Imlach was unable to recall the precise words and tune, and instead recorded his own derivation A year or two later, he taught his version of the song to his latest protege, Christy Moore. Fresh over from Ireland. Moore was introduced to the folk network by Imlach. who showed him 'Black Is The Colour' after Moore played Glasgow for the first time in 1968.

Notwithstanding its embarrassment of riches, that first album was chiefly significant for containing what would become Imlach's theme tune. Originally called Hairy Mary', Cod Liver Oil And Orange Juice' had been penned by Glaswegian folk club duo Ron Clark and Carl McDougall after they had heard what McDougall described as "one too many versions" of an Imlach staple, the Christian spiritual Virgin Mary Had A Little Baby'. The pair played the song to Archie Fisher, who began to feature it in his own shows.

"I first heard Carl MacDougall doing bits of it", Hamish explained in his early 1990s autobiography. "Then, one night at the Elbow Room in Kirkcaldy, Archie Fisher and I were sharing the night. My production number for the second hall was the original of Cod Liver Oil … ', an American spiritual called Virgin Mary Had A Little Baby'. In the first half of the show, Archie did the couple of verses that he remembered of 'Cod Liver Oil …' as a joke, and it went down a storm. I thought, 'Wait a minute, I'm doing the wrong song!' So I switched, put some laughing bits in, rearranged the verses a bit, and did some rewriting. I can't remember now what exactly I did alter, but it included … taking out references people outside Glasgow didn't understand. The song kept growing, and lines were changed. A woman called Mary Airey living in the Lake District is still plagued by the song, because her name is often written or printed as Airey, Mary!"

During the late 1960s 'Cod Liver Oil And Orange Juice' ("What a woman who was expecting a baby got free — this was in the days before Margaret Thatcher became Minister of Health" Imlach explained) was the most requested song no British Forces Radio, though it was banned from such programmes as Two Way Family Favourites after the BBC decided that, in Imlach's words, " … it was certain to be erotic and full of double meanings". The song's popularity also cost Hamish his newly-acquired job as a full-time professional performer in the Beachcomber Bar of the Butlin's Holiday Camp in Ayr. "I was sacked on the third night because of Cod Liver Oil … '", he later confessed "Several Butlin's directors were there, touring round various camps Many people had asked me for the song, and when I started doing it, together with the jokes and patter, a couple of hundred people left their seats. Instead of being scattered over this vast area among the rubber crocodiles, they came and stood in front of me, shouting encouragement. The language was unintelligible to the visiting directors from the South. They became convinced it was obscene, not the thing for a family camp. So I got my books."

Imlach's second album was a live set — given his reputation as a peerless live performer, an entirely logical step. Recorded in 1967 at the Rockfield Hotel in Paisley, the release was slightly handicapped by the fact that no material was utilised from Hamish's debut album — which, of course, had included many songs that were live favourites.

Nevertheless, Hamish Imlach Live comfortably managed to convey the widely-held notion that Hamish was born to perform, and tracks like Ewan MacColl's spine-tingling The Ballad Of Timothy Evans' and a fine rendition of Blind Blake's blues classic 'Early Morning Blues' were particularly noteworthy.

Subsequent albums explored various elements of Imlach's multifaceted character. You can probably guess the theme of the 1971 set Ballads Of Booze ("not so much a long player, more a 12 inch beer mar, reckoned the sleeve notes), which included one of Hamish's most popular performances in 'Goodbye Booze', while the following year's Fine Old English Tory Times was largely based around songs of financial hardship ('Forty Pence Butter', 'Twelve Pence Ain't A Shilling') and social injustice ('Dialogue', the excellent title track). Throughout such projects, Imlach was supported by many leading members of the Scottish folk community, including Billy Connolly's original Humblebums partner Tam Harvey, Archie Fisher and Clive Palmer, who also donated the literally-titled Clive's Song' to the 1971 album Old Rarity — an obscure but excellent release that also featured Hamish s beautiful treatment of the traditional bluesy ballad Pretty Little Horses'.

After the 1973 release Murdered Ballads — an oddball collection that incorporated country and music hall elements and was based around a clutch of songs by American writer and humorist Shel Silverstein ( A Boy Named Sue', 'Sylvia's Mother' etc), though it also featured some Ogden Nash verse — Imlach parted company with Transatlantic, although the label would continue to utilise his recordings for various compilation albums and best of packages. By this stage, Hamish's unhealthy lifestyle was finally catching up with him. Though only in his mid-thirties, he was declared to be medically dead after all bodily functions apparently gave out. But the judgment turned out to be premature, and Imlach subsequently joked that he made more money from the raft of benefit concerts that followed than he had at any other stage of his career!

Despite his poor health, he continued to work, also recording for a variety of labels — Lismor, Autogram, Kettle — and with various musical foils, including Mary Black, members of Moving Hearts and his long-term partner Muriel Graves. He appeared on Sinead O'Connor's 1990 album Lion in A Cage but of far greater consequence was a longstanding, highly productive working relationship with old friend lain Mackintosh, who had played on all his early 1970s Transatlantic albums.

In later years, and in common with so many of his contemporaries on the folk club circuit, Hamish found more receptive audiences in mainland Europe, although he also relocated to Dublin for a while. Eventually, however, his body finally gave out on him. Four years after publishing his autobiography, Cod Liver Oil and The Orange Juice: Reminiscences Of A Fat Folk Singer, he died at his Motherwell home on the first day of 1996 at the age of fifty-five. He had suffered from bronchial and asthmatic complaints for years, and a virulent dose of influenza, combined with his determination to carry on working, proved too much for his ailing body to withstand.

In some ways, it was a fitting end to a life of legendary excess. Td always joked about my drinking and smoking that I would hate to die with a heart attack and have a good liver, kidneys and brains", Imlach had remarked in his autobiography. "When I die, I want everything to be knackered!"

David Wells

April 2006

With acknowledgements to Cod Liver Oil and The Orange Juice: Confessions Of A Fat Folk Singer, Hamish Imlach with Ewan McVicar, published in 1992 by Mainstream Publishing (ISBN 185 1585125).