|

|

Sleeve Notes

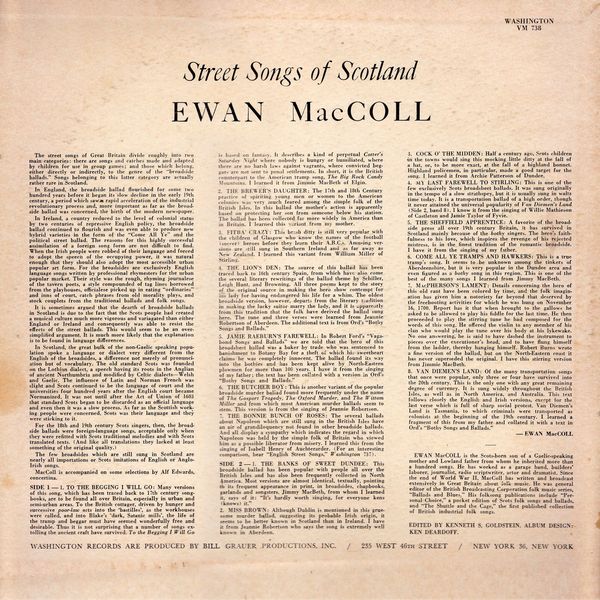

The street songs of Great Britain divide roughly into two main categories: there are songs and catches made and adapted by children for use in group games; and those which belong, either directly or indirectly, to the genre of the "broadside ballads." Songs belonging to this latter category are actually rather rare in Scotland.

In England., the broadside ballad flourished for some two hundred years before it began its slow decline in the early 19th century, a period which saw a rapid acceleration of the industrial revolutionary process and, more important as far as the broadside ballad was concerned, the birth of the modern newspaper.

In Ireland, a country reduced to the level of colonial status by two centuries of repressive English policy, the broadside ballad continued to flourish and was even able to produce new hybrid varieties in the form of the "Come All Ye" and the political street ballad. The reasons for this highly successful assimilation of a foreign song form are not difficult to find. When the Irish people were robbed of their language and forced to adopt the speech of the occupying power, it was natural enough that they should also adopt the most accessible urban popular art form. For the broadsides are exclusively English language songs written by professional rhymesters for the urban popular market. Their style was the rough, rhyming journalese of the tavern poets, a style compounded of tag lines borrowed from the playhouses, officialese picked up in eating "ordinaries" and inns of court, catch phrases from old morality plays, and stock couplets from the traditional ballads and folk songs.

It is sometimes argued that the dearth of broadside ballads in Scotland is due to the fact that the Scots people had created a musical culture much more vigorous and variagated than either England or Ireland and, consequently, was able to resist the effects of the street ballads. This would seem to be an oversimplified argument. It is much more likely that the explanation is to be found in language differences.

In Scotland, the great bulk of the non-Gaelic speaking population spoke a language or dialect very different from the English of the broadsides, a difference not merely of pronunciation but of vocabulary. The old standard Scots was founded on the Lothian dialect, a speech having its roots in the Anglian of ancient Northumbria and modified by Celtic dialects—Welsh and Gaelic. The influence of Latin and Norman French was slight and Scots continued to be the language of court and the universities four hundred years after the English court became Normanized. It was not until after the Act of Union of 1603 that standard Scots began to be discarded as an official language and even then it was a slow process. As far as the Scottish working people were concerned, Scots was their language and they were sticking to it.

For the 18th and 19th century Scots singers, then, the broadside ballads were foreign-language songs, acceptable only when they were refitted with Scots traditional melodies and with Scots translated texts. (And like all translations they lacked at least something of the original quality.) The few broadsides which are still sung in Scotland are nearly all importations or Scots imitations of English or Anglo-Irishsongs.

TO THE BEGGING I WILL GO: Many versions of this song, which has been traced back to 17th century song-books, are to be found all over Britain, especially in urban and semi-urban areas. To the British cottager, driven by hunger and successive poor-law acts into the 'bastilles', as the workhouses were called, and into Blake's 'dark, Satanic mills', the life of the tramp and beggar must have seemed wonderfully free and desirable. Thus it is not surprising that a number of songs extolling the ancient craft have survived. To the Begging I Will Go is based on fantasy. It describes a kind of perpetual Cotter's Saturday Night where nobody is hungry or humiliated, where there are no harsh laws against vagrants, where convicted beggars are not sent to penal settlements. In short, it is the British counterpart to the American tramp song, The Big Rock Candy Mountains. I learned it from Jimmie MacBeth of Elgin.

THE BREWER'S DAUGHTER: The 17th and 18th century practice of spiriting young men or women to the American colonies was very much feared among the simple folk of the British Isles. In this ballad the mother's action is apparently based on protecting her son from someone below his station. The ballad has been collected far more widely in America than in Britain. I learned this variant from my mother.

FITBA' CRAZY: This brash ditty is still very popular with the children of Glasgow who know the names of the football 'soccer' heroes before they learn their A.B.C.s. Amuising versions are still sung in Southern Ireland and as far away as New Zealand. I learned this variant from William Miller of Stirling.

THE LION'S DEN: The source of this ballad has been traced bark to 16th century Spain, from which have also come the several literary rewritings of the ballad theme by Schiller, Leigh Hunt, and Browning. All three poems kept to the story of the original source in making the hero show contempt for his lady for having endangered his life for a whim. The oldest broadside version, however, departs from the literary tradition m making the lucky suitor marry the lady, and it is apparently from this tradition that the folk have derived the ballad sung here. The tune and three verses were learned from Jeannie Robertson of Aberdeen. The additional text is from Ord's "Bothy Songs and Ballads."

JAMIE RAEBURN'S FAREWELL: In Robert Ford's "Vagabond Songs and Ballads" we are told that the hero of this broadsheet ballad was a baker by trade who was sentenced to banishment to Botany Bay for a theft of which his sweetheart claims he was completely innocent. The ballad found its way into the bothies and has been kept alive by North-Eastern plowmen for more than 100 years. I have it from the singing of my father; the text has been collated with a version in Ord's "Bothy Songs and Ballads."

THE BUTCHER BOY: This is another variant of the popular broadside murder ballad found more frequently under the name of The Gosport Tragedy, The Oxford Murder, and The W ittan Miller and from which most American murder ballads seem to stem. This version is from the singing of Jeannie Robertson.

THE BONNIE BUNCH OF ROSES: The several ballads about Napoleon which are still sung in the British Isles have an air of grandiloquency not found in other broadside ballads. And all display a sympathy which indicates the regard in which Napoleon was held by the simple folk of Britain who viewed a possible liberator from misery. I learned this from the of Isabell Henry of Auchterarder. (For an interesting caparison. hear "English Street Songs." Riverside RLP 12-614).

THE BANKS OF SWEET DUNDEE: This broadside ballad has been popular with people all over the British Isles and has also been frequently collected in North America. Most versions are almost identical, textually, pointing to its frequent appearance in print, in broadsides, chapbooks, garlands and songsters. Jimmy MacBeth, from whom I learned it, says of it: "It's hardly worth singing, for everyone kens (knows) it."

MISS BROWN: Although Dublin is mentioned in this gruesome murder ballad, suggesting its probable Irish origin, it seems to be better known in Scotland than in Ireland. I have it from Jeannie Robertson who says the song is extremely well known in Aberdeen. (For a fuller version, hear The Dublin Murder Ballad sung by Patrick Galvin in "Irish Street Songs," Riverside RLP 12-613).

COCK O' THE MIDDEN: Half a century ago, Scots children in the towns would sing this mocking little ditty at the fall of a hat, or, to be more exact, at the fall of a highland bonnet. Highland policemen, in particular, made a good target for the song. I learned it from Archie Patterson of Dundee.

MY LAST FAREWELL TO STIRLING: This is one of the few exclusively Scots broadsheet ballads. It was sung originally in the tempo of a slow strathspey, but it is usually sung in waltz time today. It is a transportation ballad of a high order, though it never attained the universal popularity of Van Diemen's Land (Side 2, band 8). I know it from the singing of Willie Mathieson of Castleton and Jamie Taylor of Fyvie.

THE SHEFFIELD APPRENTICE: A favorite of the broadside press all over 19th century Britain, it has survived in Scotland mainly because of the bothy singers. The hero's faithfulness to his love, which inspires the revenge of his rejected mistress, is in the finest tradition of the romantic broadside. I have it from the singing of my father.

COME ALL YE TRAMPS AND HAWKERS: This is a true tramp's song. It seems to be unknown among the tinkers of Aberdeenshire, hut is very popular in the Dundee area and even figured as a bothy song in this region. This is one of the best of the many songs I learned from Jimmy MacBeth.

MacPHERSON'S LAMENT: Details concerning the hero of this old rant have been colored by time, and the folk imagination has given him a notoriety far beyond that deserved by the freebooting activities for which he was hung on November 16, 1700. Report has it that when brought to the gallows he asked to he allowed to play his fiddle for the last time. He then proceeded to play the stirring tune he had composed for the words of this song. He offered the violin to any member of his clan who would play the tune over his body at his lykewake. No one answering, he is said to have dashed the instrument to pieces over the executioner's head, and to have flung himself from the ladder, thereby hanging himself. Robert Burns wrote a fine version of the ballad, but on the North-Eastern coast it has never superseded the original. I have this stirring version from Jimmie MacBeth.

VAN DIEMEN'S LAND: Of the many transportation songs that once were popular, only three or four have survived into the 20th century. This is the only one with any great remaining degree of currency. It is sung widely throughout the British Isles, as well as in North America, and Australia This text follows closely the English and Irish versions, except for the last verse which is full of sharp social protest. Van Diemen's Land is Tasmania, to which criminals were transported as colonists at the beginning of the 19th century. I learned a fragment of this from my father and collated it with a text in Ord's "Bothy Songs and Ballads."

Notes by Ewan MacColl

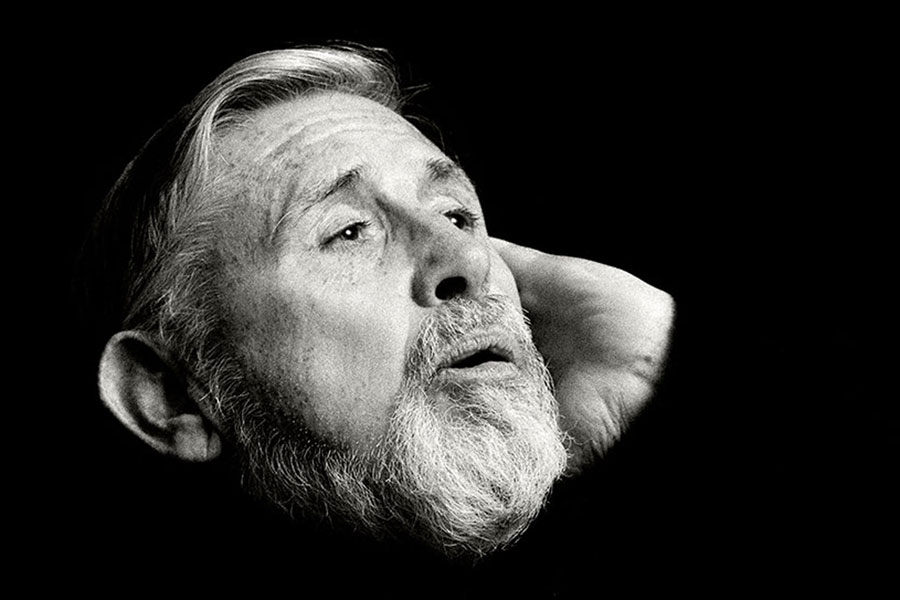

A NOTE ABOUT THE SINGER

EWAN MacCOLL is the Scots-born son of a Gaelic-speaking mother and Lowland father from whom he inherited more than a hundred songs. He has worked as a garage hand, builders' laborer, journalist, radio scriptwriter, actor and dramatist. Since the end of World War II, MacColl has written and broadcast extensively in Great Britain about folk music. He was general editor of the British Broadcasting Corporation folk music series, "Ballads and Bines," and frequently took part in Alan Lomax's radio and television shows for B.B.C. His folksong publications include "Personal Choice," a pocket edition of Scots folk songs and ballads, and "The Shuttle and the Cage," the first published collection of British industrial folk songs. He is also represented in the Riverside Folklore Series by albums of SCOTS DRINKING SONGS (RLP 12-605) and SCOT FOLK SONGS (RLP 12-609).

K.S.G.