|

|

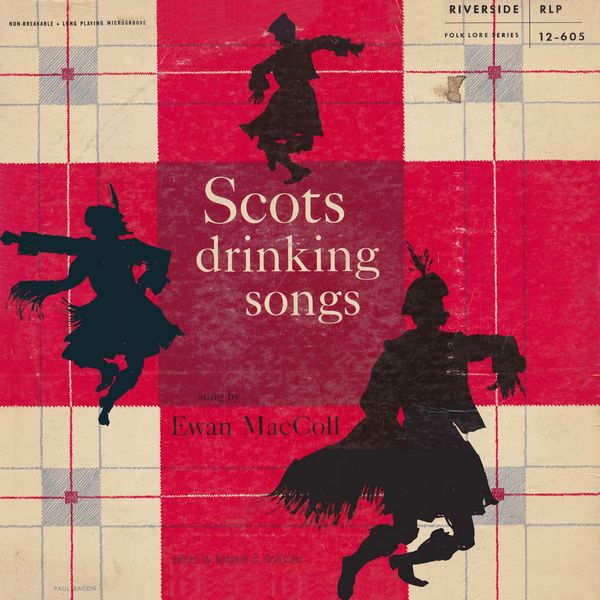

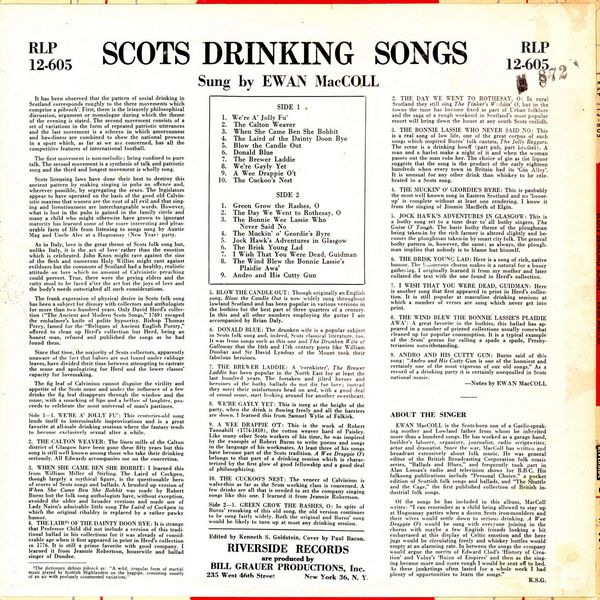

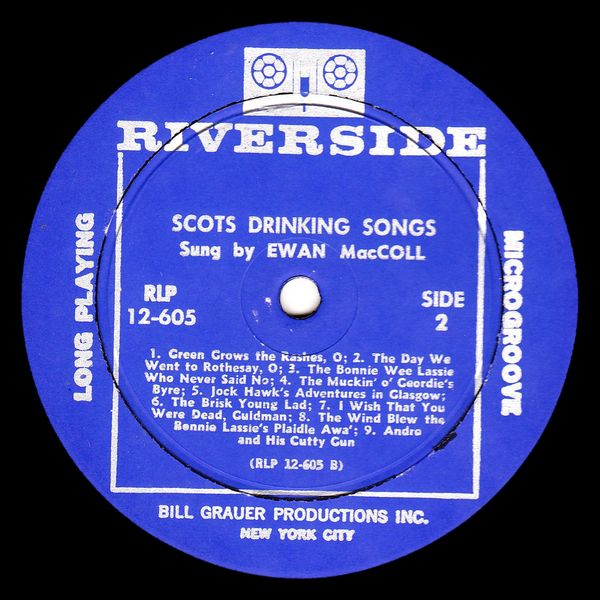

Sleeve Notes

It has been observed that the pattern of social drinking in Scotland corresponds roughly to the three movements which comprise a pibroch [1]. First, there is the leisurely philosophical discussion, argument or monologue during which the theme of the evening is stated. The second movement consists of a set of variations in the form of repeated patriotic utterances and the last movement is a scherzo in which amorousness and bawdiness are combined to show the national prowess in a sport which, as far as we are concerned, has all the competitive features of international football.

The first movement is non-melodic; being confined to pure talk. The second movement is a synthesis of talk and patriotic song and the third and longest movement is wholly song.

Scots licensing laws have done their best to destroy this ancient pattern by making singing in pubs an offence and, wherever possible, by segregating the sexes. The legislators appear to have operated on the basis of the good old Calvinistic maxims that women are the root of all evil and that singing and licentiousness are interchangeable words. However, what is lost in the pubs is gained in the family circle and many a child who might otherwise have grown to ignorant maturity has learned some of the more interesting and pleasurable facts of life from listening to songs sung by Auntie Mag and Uncle Alec at a Hogmanay (New Year) party.

As in Italy, love is the great theme of Scots folk song but, unlike Italy, it is the act of love rather than the emotion which is celebrated. John Knox might rave against the sins of the flesh and numerous Holy Willies might rant against evildoers but the commons of Scotland had a healthy, realistic attitude on love which no amount of Calvinistic preaching could pervert. True, there were the prying elders and the cutty stool to be faced after the act but the joys of love and the body's needs outweighed all such considerations.

The frank expression of physical desire in Scots folk song has been a subject for dismay with collectors and anthologists for more than two hundred years. Only David Herd's collection ("The Ancient and Modern Scots Songs," 1769) escaped the embalmer's knife of polite hypocrisy. Bishop Thomas Percy, famed for the "Reliques of Ancient English Poetry," offered to clean up Herd's collection but Herd, being an honest man, refused and published the songs as he had found them.

Since that time, the majority of Scots collectors, apparently unaware of the fact that babies are not found under cabbage leaves, have divided their time between attempting to castrate the muse and apologizing for Herd and the lower classes' capacity for lovemaking.

The fig leaf of Calvinism cannot disguise the virility and appetite of the Scots muse and under the influence of a few drinks the fig leaf disappears through the window and the muse, with a smacking of lips and a bellow of laughter, proceeds to celebrate the most universal of man's pastimes.

1 The dictionary defines pibroch as: "A wild, irregular form of martial music played by Scottish Highlanders on the bagpipe, consisting usually of an air with profusely ornamented variations."

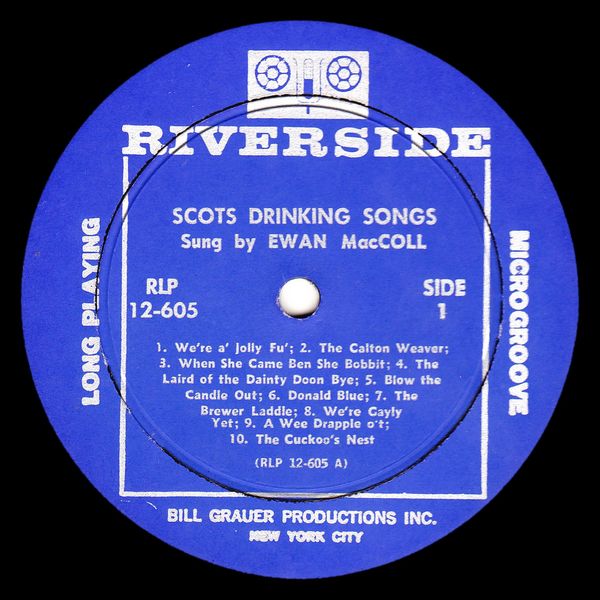

WE'RE A' JOLLY FU': This centuries-old song lends itself to interminable improvizations and is a great favorite at all-male drinking sessions where the fantasy tends to become exclusively sexual after a while.

THE CALTON WEAVER: The linen mills of the Calton district of Glasgow have been gone these fifty years but this song is still well known among those who take their drinking seriously. Alf Edwards accompanies me on the concertina.

WHEN SHE GAME BEN SHE BOBBIT: I learned this from William Miller of Stirling. The Laird of Cockpen, though largely a mythical figure, is the questionable hero of scores of Scots songs and ballads. A brushed up version of this song was made by Robert Burns but the folk song anthologists have, without exception, avoided the older and broader versions and made use of Lady Nairn's admirable little song The Laird of Cockpen in which the original ribaldry is replaced by a rather pawky humor.

THE LAIRD OF THE DAINTY DOON BYE: It is strange that Professor Child did not include a version of this traditional ballad in his collections for it was already of considerable age when it first appeared in print in Herd's collection in 1776. It is still a prime favorite with good company. I learned it from Jeannie Robertson of Dundee.

BLOW THE CANDLE OUT: Originally an English song, but now widely sung throughout lowland Scotland. It has been popular in various versions in the bothies for the best part of three quarters of a century. In this and all other numbers employing the guitar I am accompanied by Brian Daly.

DONALD BLUE: The drunken wife is a popular subject in Scots folk song and, indeed, Scots classical literature, too. It was from songs such as this one and The Drunken Wife of Galloway that the 16th and 17th century poets like William Dunbar and Sir David Lyndsay of the Mount took their fabulous heroines.

THE BREWER LADDIE: A 'cornkister', this song has been popular in the North East for at least the last hundred years. The forsaken and jilted heroes and heroines of the bothy ballads do not die for love; instead they meet their misfortunes head on and, with a good deal of sound sense, start looking around for another sweetheart.

WE'RE GAYLY YET: This is sung at the height of the party, when the drink is flowing freely and all the barriers are down. I learned this from Samuel Wylie of Falkirk.

A WEE DRAPPIE O'T: This is the work of Robert Tannahill (1774-1810), the cotton weaver bard of Paisley. Like many other Scots workers of his time, he was inspired by the example of Robert Burns to write poems and songs in the language of his workmates. At least three of his songs have become part of the. Scots tradition. This one belongs to that part of a drinking session which is characterized by the first glow of good fellowship and a good deal of philosophizing.

THE CUCKOO'S NEST: The veneer of Calvinism is wafer-thin as far as the Scots working class is concerned. A few drinks are all that is needed to set the company singing songs like this one. I learned it from Jeannie Robertson.

(GREEN GROW THE RASHES, O: In spite of Burns' remaking of this old song, the old version continues to be sung fairly widely. Both the original and Burns' song would be likely to turn up at most any drinking session.

THE DAY WE WENT TO ROTHESAY, O: In rural Scotland they still sing The Tinker's Weddin' O, but in the towns the tune has become fixed as part of Urban folklore and the saga of a rough weekend in Scotland's most popular resort will bring down the house at any south Scots ceilidh.

THE BONNIE LASSIE WHO NEVER SAID NO: This is a real song of low life, one of the great corpus of such songs which inspired Burns' folk cantata, The Jolly Beggars. The scene is a drinking howff (part pub, part brothel). A man and a harlot make a night of it and when the woman passes out the man robs her. The choice of gin as the liquor suggests that the song is the product of the early eighteen hundreds when every town in Britain had its 'Gin Alley'. It is unusual for any other drink than whiskey to be celebrated in a Scots song.

THE MUCKIN' O' GEORDIE'S BYRE: This is probably the most well known song in Eastern Scotland and no "boose-up" is complete without at least one rendering. I know it from the singing of Jimmie MacBeth of Elgin.

JOCK HAWK'S ADVENTURES IN GLASGOW: This is a bothy song set to a tune dear to all bothy singers, The Guise O' Tough. The basic bothy theme of the ploughman being taken-in by the rich farmer is altered slightly and becomes the ploughman taken-in by smart city folk. The general bothy pattern is, however, the same; as always, the ploughman implies that nobody is to blame but himself.

THE BRISK YOUNG LAD: Here is a song of rich, native humor. The boisterous chorus makes it a natural for a boozy gathering. I originally learned it from my mother and later collated the text with the one found in Herd's collection.

I WISH THAT YOU WERE DEAD, GUIDMAN: Here is another song that first appeared in print in Herd's collection. It is still popular at masculine drinking sessions at which a number of verses are sung which never get into print.

THE WIND BLEW THE BONNIE LASSIE'S PLAIDIE AWA': A great favorite in the bothies, this ballad has appeared in a number of printed collections usually somewhat cleaned up for popular consumption. It is a typical example of the Scots' genius for calling a spade a spade, Presbyterianism notwithstanding.

ANDRO AND HIS CUTTY GUN: Burns described this as "one of the bonniest and certainly one of the most vigorous of our old songs." As a record of a drinking party it is certainly unequaled in Scots national music.

— EWAN MacCOLL

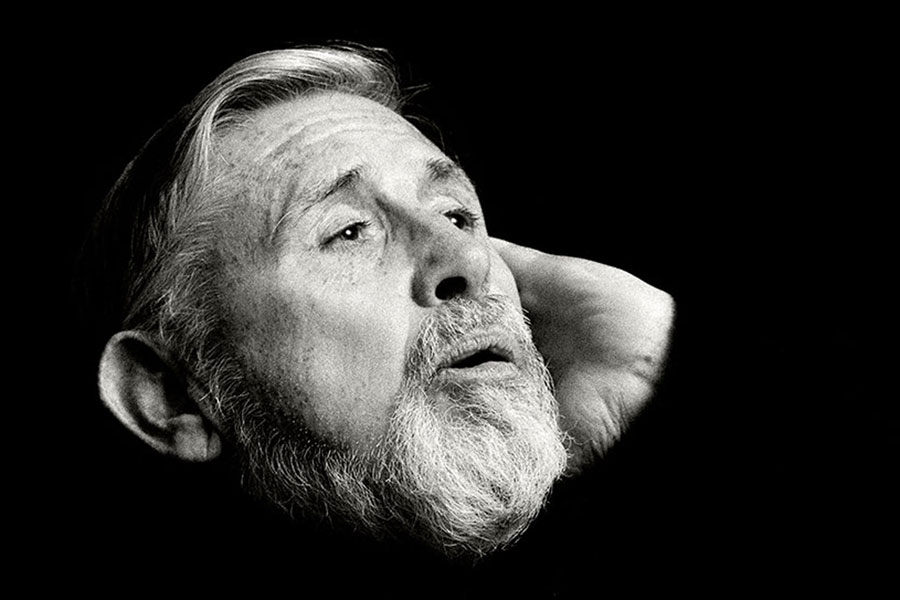

About the singer:

EWAN MacCOLL is the Scots-born son of a Gaelic-speaking mother and Lowland father from whom he inherited more than a hundred songs. He has worked as a garage hand, builder's laborer, organizer, journalist, radio scriptwriter, actor and dramatist. MacColl has written and broadcast extensively about folk music, was general editor of the British Broadcasting Corporation folk music series. "Ballads and Blues," and frequently took part in Alan Lomax's radio and television shows for B.B.C.

Of the songs he has included in this album, MacColl writes: "I can remember as a child being allowed to stay up at Hogmanay parties when a dozen Scots iron-moulders and their wives would settle down to serious drinking. A Wee Drappie O't would be sung with everyone joining in the chorus with maybe a few English friends looking a bit embarrassed at this display of Celtic emotion and the beer jugs would be circulating freely and whiskey bottles would empty at an alarming rate. In between the songs the company would argue the merits of Edward Clod's 'History of Creation' and Volny's 'Ruins of Empires' and then as the singing became more and more rough I would be sent off to bed. As these junketings often lasted for a whole week I had plenty of opportunities to learn the songs."