|

|

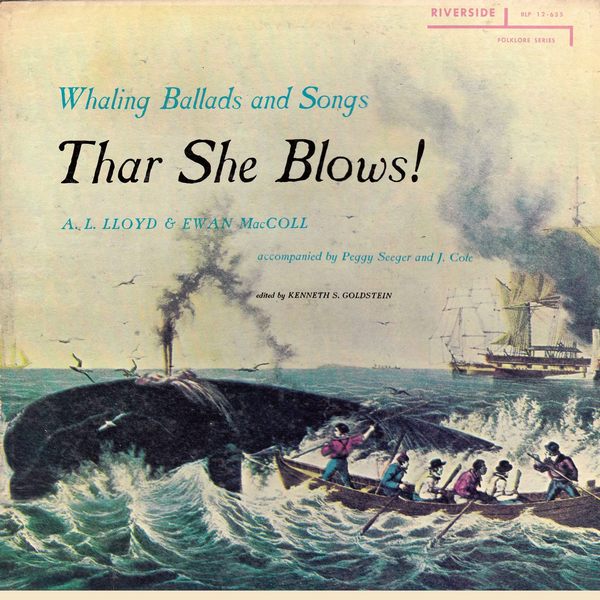

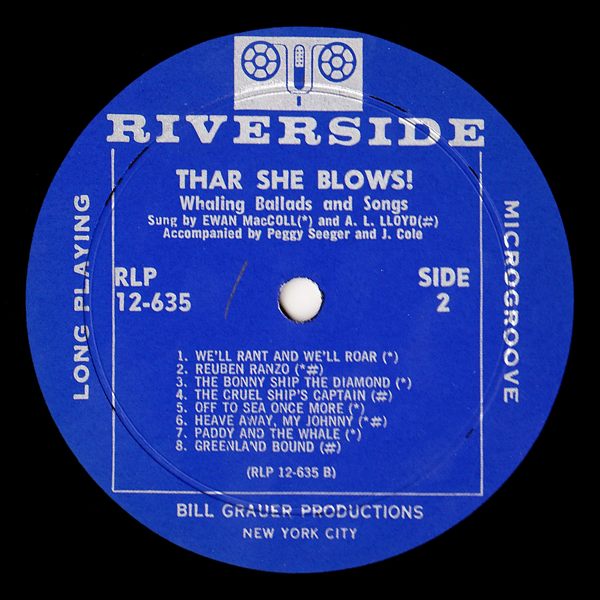

Sleeve Notes

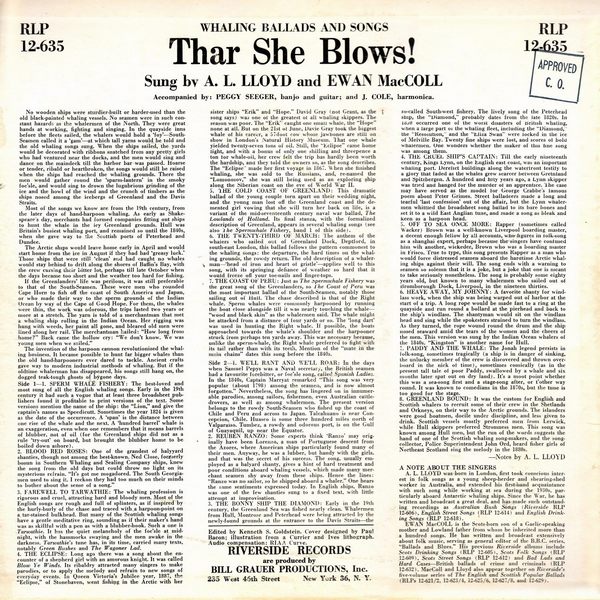

No wooden ships were sturdier-built or harder-used than the old black-painted whaling vessels. No seamen were in such constant hazards as the whalermen of the North. They were great hands at working, fighting and singing. In the quayside inns before the fleets sailed, the whalers would hold a 'foy' — South-Seamen called it a 'gam' — at which tall yarns would be told and the old whaling songs sung. When the ships sailed, the yards would be decorated with ribbons snatched from any pretty girls who had ventured near the docks, and the men would sing and dance on the maindeck till the harbor bar was passed. Hoarse or tender, ribald or heartbroken, the songs would still be raised when the ships had reached the whaling grounds. There the men would gather round the 'sparm-lantern' in the smoky foc'sle, and would sing to drown the lugubrious grinding of the ice and the howl of the wind and the crunch of timbers as the ships nosed among the icebergs of Greenland and the Davis Straits.

Most of the songs we know are from the 19th century, from the later days of hand-harpoon whaling. As early as Shakespeare's day, merchants had formed companies fitting out ships to hunt the whale in the icy Greenland grounds. Hull was Britain's busiest whaling port, and remained so until the 1840s, when she gave way to the Scottish ports of Peterhead and Dundee.

The Arctic ships would leave home early in April and would start home from the ice in August if they had had 'greasy luck.' Those ships that were still 'clean' and had caught no whales would stay behind to drift along the shores of Baffin's Bay, with the crew cursing their bitter lot, perhaps till late October when the days became too short and the weather too hard for fishing. If the Greenlanders' life was perilous, it was still preferable to that of the South-Seamen. These were men who rounded Cape Horn to fish off the coast of South America and Japan, or who made their way to the sperm grounds of the Indian Ocean by way of the Cape of Good Hope. For them, the whales were thin, the work was odorous, the trips lasted two years or more at a stretch. The yarn is told of a merchantman that met a whaling ship rolling in the Indian Ocean. Her rigging was hung with weeds, her paint all gone, and bleared old men were lined along her rail. The merchantman hailed: "How long from home?" Back came the hollow cry: "We don't know. We was young men when we sailed."

The invention of the harpoon cannon revolutionized the whaling business. It became possible to hunt far bigger whales than the old hand-harpooners ever dared to tackle. Ancient crafts gave way to modern industrial methods of whaling. But if the oldtime whalerman has disappeared, his songs still hang on, the dogged teak-tough ghosts of bygone days.

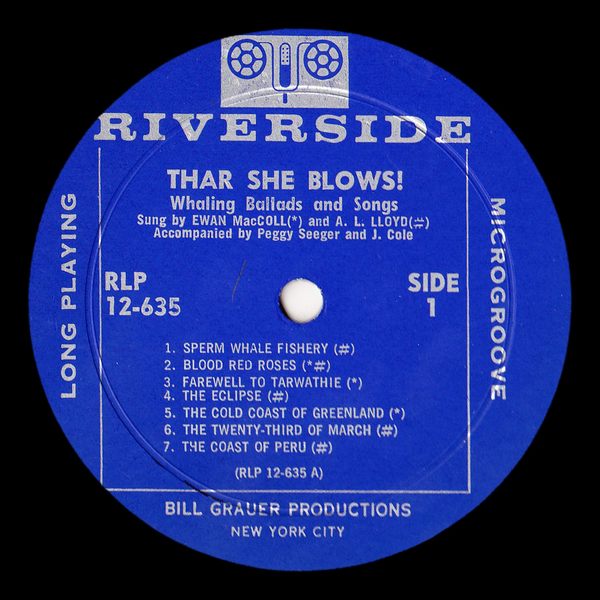

SPERM WHALE FISHERY: The best-loved and most sung of all the English whaling songs. Early in the 19th century it had such a vogue that at least three broadsheet publishers found it profitable to print versions of the text. Some versions mention the name of the ship: the "Lion," and give the captain's names as Speedicutt. Sometimes the year 1824 is given as the date of the occurrence. A 'span' is the distance between one rise of the whale and the next. A 'hundred barrel' whale is an exaggeration, even when one remembers that it means barrels of blubber, not of oil (for the Greenland ships did not as a rule 'try-out' on board, but brought the blubber home to be boiled down ashore).

BLOOD RED ROSES: One of the grandest of halyyard shanties, though not among the best-known. Ned Close, formerly bosun in Southern Whaling and Sealing Company ships, knew the song from the old days but could throw no light on its mysterious refrain. "It's got me mogadored. The South Georgia-men used to sing it. I reckon they had too much on their minds to bother about the sense of a song.".

FAREWELL TO TARWATHIE: The whaling profession is rigorous and cruel, attracting hard and bloody men. Most of the English songs are rough and full of splinters, as if inspired by the hurly-burly of the chase and traced with,a harpoon-point on a tar-stained bulkhead. But many of the Scottish whaling songs have a gentle meditative ring, sounding as if their maker's hand was as skillful with a pen as with a blubber-hook. Such a one is Tarwathie. It has the quiet melancholy of the foc'sle at midnight, with the hammocks swaying and the men awake in the darkness. Tarwathie's tune has, in its time, carried many texts, notably Green Bushes and The Wagoner Lad.

THE ECLIPSE: Long ago there was a song about the encounter of a shepherd girl with an amorous knight. It was called Blow Ye Winds. Its ribaldry attracted many singers to make parodies, or to apply the melody and refrain to new songs of everyday events. In Queen Victoria's Jubilee year, 1887, the "Eclipse," of Stonehaven, went fishing in the Arctic with her sister ships "Erik" and "Hope." David Gray (not Grant, as the song says) was one of the greatest of all whaling skippers. The season was poor. The "Erik" caught one small whale, the "Hope" none at all. But on the 21st of June, Davie Gray took the biggest whale of his career, a 57-foot cow whose jawbones are still on show in London's Natural History Museum. That one whale yielded twenty-seven tons of oil. Still, the '"Eclipse" came home light, and with a bonus of only one shilling and threepence a ton tor whale-oil, her crew felt the trip has hardly been worth the hardship, and they told the owners so, as the song describes. The "Eclipse" made her first voyage in 1867. When she finished whaling, she was sold to the Russians, and, re-named the "Lomonosov," she was still being used as an exploring ship along the Siberian coast on the eve of World War II.

THE COLD COAST OF GREENLAND: This dramatic ballad of the young couple torn apart on their wedding night, and the young man lost off the Greenland coast and the demented girl vowing that she will turn her back on life, is a variant of the mid-seventeenth century naval war ballad, The Lowlands of Holland. Its final stanza, with the formalized description of Greenland, appears in several whaling songs (see also 'The Spermwhale Fishery, baud 1 of this side).

THE TWENTY-THIRD OF MARCH: The anthem of the whalers who sailed out of Greenland Dock, Deptford, in south-east London, this ballad follows the pattern commonest to the whaling songs: the departure, the hard times on the whaling grounds, the rowdy return. The old description of a whaler-man — 'head of iron and heart of gristle' — applies well to this song, with its springing defiance of weather so hard that it would freeze off your toe-nails and finger-tops.

THE COAST OF PERU: Just as The Spermwhale Fishery was the great song of the Greenlanders, so The Coast of Peru was the most important ballad of the South-Seamen, notably those sailing out of Hull. The chase described is that of the Right whale. Sperm whales were commonly harpooned by running the boat close alongside till it was nearly touching the whale — "wood and black skin" as the whalermen said. The whale might be attacked from a distance of four yards or so. The 'long dart" was used in hunting the Right whale. If possible, the boats approached towards the whale's shoulder and the harpooner struck from perhaps ten yards away. This was necessary because, unlike the sperm-whale, the Right whale preferred to fight with its tail rather than with its teeth. Mention of the "mate in the main chains" dates this song before the 1840s.

WE'LL RANT AND WE'LL ROAR: In the days when Samuel Pepys was a Naval secretary, the British seamen had a favourite forebitter, or foc'sle song, called Spanish Ladies. In the 1840s, Captain Marryat remarked "This song was very popular (about 1798) among the seamen, and is now almost forgotten."Nevertheless, the song has lingered on in innumerable parodies, among sailors, fishermen, even Australian cattle-drovers, as well as among whalermen. The present version belongs to the rowdy South-Seamen who fished up the coast of Chile and Peru and across to Japan. Talcahuaiio is near Con-cepcion, Chile. Huasco is some three hundred miles north of Valparaiso. Tumbez, a rowdy and odorous port, is on the Gulf of Guayaquil, up near the Equator.

REUBEN RANZO: Some experts think 'Ranzo' may originally have been Lorenzo, a man of Portuguese descent from the Azores, where American ships particularly found many of their men. Anyway, he was a lubber, but handy with the girls, and that was the secret of his success. The song, usually employed as a halyard shanty, gives a hint of hard treatment and poor conditions aboard whaling vessels, which made many merchant seamen shy away from these ships. Hence the lines: "Ranzo was no sailor, so he shipped aboard a whaler." One hears the same sentiments expressed today. In English ships, Ranzo was one of the few shanties sung to a fixed text, with little attempt at improvisation.

THE BONNY SHIP THE DIAMOND: Early in the 19th century, the Greenland Sea was fished nearly clean. Whalermen from Hull, Montrose and Peterhead were being attracted by the newly-found grounds at the entrance to the Davis Straits — the so-called South-west fishery. The lively song of the Peterhead ship, the "Diamond," probably dates from the late 1820s. In 1830 occurred one of the worst disasters of british whaling, when a large part of the whaling fleet, including the "Diamond,' the "Resolution," and the "Eliza Swan" were locked in the ice of Melville Bay. Twenty fine ships were lost, and scores of bold whalermen. One wonders whether the maker of this fane song was among them.

THE CRUEL SHIP'S CAPTAIN: Till the early nineteenth century, Kings Lynn, on the English east coast, was an important whaling port. Derelict buildings along the waterfront testily to a glory that laded as the whales grew scarcer between Greenland and Spitzbergen. A hundred and fifty years ago, a Lynn skipper was tried and hanged for the murder of an apprentice. The case may have served as the model lor George Crabbe's famous poem about Peter Grimes. Street balladeers made a long and tearful 'last confession' out of the affair, but the Lynn whaler-men whittled the broadsheet song ballad to its bare bones and set it to a wild East Anglian tune, and made a song as bleak and keen as a harpoon head.

OFF TO SEA ONCE MORE: Rapper (sometimes called Wacker) Brown was a well-known Liverpool boarding master, a decent enough fellow by all accounts, who figures in folk-song as a shanghai expert, perhaps because the singers have confused him will another, wickeder, Brown who was a boarding master in Frisco. True to type, this song presents Rapper as a man who would force distressed seamen aboard the hardtime Arctic whaling ships against their will. The song ends with a warning to seamen so solemn that it is a joke, but a joke that one is meant to take seriously nonetheless. The song is probably some eighty years old, but known to many whalermen who sailed out of Bromborough Dock, Liverpool, in the nineteen thirties.

HEAVE AWAY, MY JOHNNY: A favorite shanty for windlass work, when the ship was being warped out of harbor at the start of a trip. A long rope would be made fast to a ring at the quayside and run round a bollard at the pierhead and back to the ship's windlass. The shantyman would sit on the windlass head and sing while the spokesters strained to turn the windlass. As they turned, the rope wound round the drum and the ship nosed seaward amid the tears of the women and the cheers of the men. This version was sung by the Indian Ocean whalers of the 1840s. "Kingston" is another name for Hull.

PADDY AND THE WHALE: The Jonah legend persists in folk-song, sometimes tragically (a ship is in danger of sinking, the unlucky member of the crew is discovered and thrown overboard in the nick of time), sometimes comically (as in the present tall tale of poor Paddy, swallowed by a whale and six months later spat out on dry land). It's a moot point whether this was a sea-song first and a stage-song after, or t'other way round. It was known to comedians in the 1870s, but the tune is too good for the stage.

GREENLAND BOUND: It was the custom for English and Scottish whalers to recruit some of their crew in the Shetlands and Orkneys, on their way to the Arctic grounds. The islanders were good boatmen, docile under discipline, and less given to drink. Scottish vessels mostly preferred men from Lerwick, while Hull skippers preferred Stromness men. This song was known among Hull men, but the run of the words suggests the hand of one of the Scottish whaling song-makers, and the song-collector, Police Superintendent John Ord, heard fisher girls of Northeast Scotland sing the melody in the 1880s.

— Notes by A. L. LLOYD

A NOTE ABOUT THE SINGERS

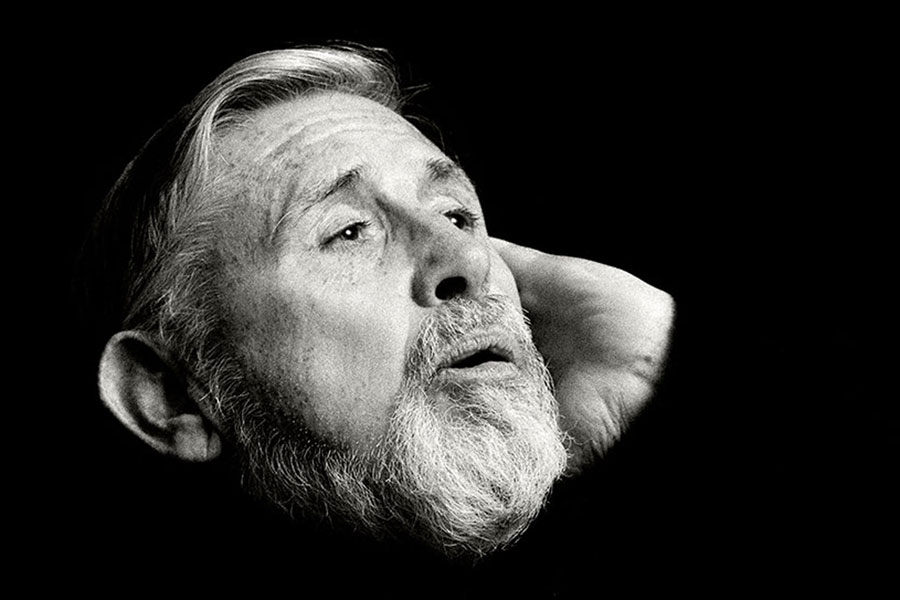

A. L. LLOYD was born in London, first took conscious interest in folk songs as a young sheep-herder and shearing-shed worker in Australia, and extended his first-hand acquaintance with such song while working at sea during the 1930s, particularly aboard Antarctic whaling ships. Since the War, he has written and broadcast a great deal, and has made such outstanding recordings as Australian Bush Songs (Riverside RLP 12-606), English Street Songs (RLP 12-614) and English Drinking Songs (RLP 12-618).

EWAN MacCOLL is the Scots-born son of a Gaelic-speaking mother and Lowland father from whom he inherited more than a hundred songs. He has written and broadcast extensively about folk music, serving as general editor of the B.B.C. series. "Ballads and Blues." His previous Riverside albums include Scots Drinking Songs (RLP 12-605), Scots Folk Songs (RLP 12-609), Scots Street Songs (RLP 12-612) and Bad Lads and Hard Cases — British ballads of crime and criminals (RLP 12-632). MacColl and Lloyd also appear together on Riverside's five-volume series of The English and Scottish Popular Ballads (RLPs 12-621 - 12-629).