|

|

Sleeve Notes

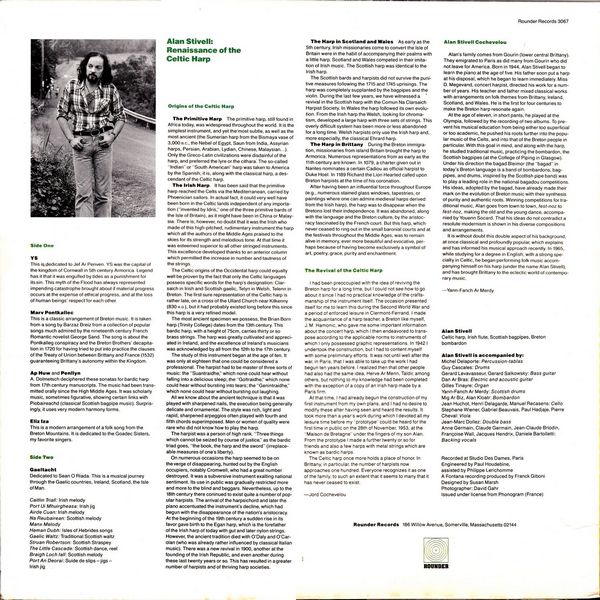

YS — This is dedicated to Jef Ar Penven. YS was the capital of the kingdom of Cornwall in 5th century Armorica. Legend has it that it was engulfed by tides as a punishment for its sin. This myth of the Flood has always represented impending catastrophe brought about if material progress occurs at the expense of ethical progress, and at the loss of human beings' respect for each other.

Marv Pontkallec — This is a classic arrangement of Breton music. It is taken from a song by Barzaz Breiz from a collection of popular songs much admired by the nineteenth century French Romantic novelist George Sand. The song is about the Pontkalleg conspiracy and the Breton Brothers' decapitation in 1720 for having tried to put into practice the clauses of the Treaty of Union between Brittany and France (1532) guaranteeing Brittany's autonomy within the Kingdom.

Ap Huw and Penllyn — A. Dolmetsch deciphered these sonatas for bardic harp from 17th century manuscripts. The music had been transmitted orally since the High Middle Ages. It was scholarly music, sometimes figurative, showing certain links with Piobaireachd (classical Scottish bagpipe music). Surprisingly, it uses very modern harmony forms.

Eliz Iza — This is a modern arrangement of a folk song from the Breton Mountains. It is dedicated to the Goadec Sisters, my favorite singers.

Two Gaeltacht — Dedicated to Seán O Riada. This is a musical journey through the Gaelic countries, Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man.

Origins of the Celtic Harp

The Primitive Harp — The primitive harp, still found in Africa today, was widespread throughout the world. It is the simplest instrument, and yet the most subtle, as well as the most ancient (the Sumerian harp from the Bismaya vase of 3,000 b.c., the Nebel of Egypt, Saun from India, Assyrian harps, Persian, Arabian, Lydian, Chinese, Malaysian …). Only the Greco-Latin civilizations were disdainful of the harp, and preferred the lyre or the cithara'. The so-called "Indian" or "South American" harp was taken to America by the Spanish; it is, along with the classical harp, a descendant of the Celtic harp.

The Irish Harp — It has been said that the primitive harp reached the Celts via the Mediterranean, carried by Phoenician sailors. In actual fact, it could very well have been born in the Celtic lands independent of any importation ("invented by Idris," one of the three primitive bards of the Isle of Britain), as it might have been in China or Malaysia. There is, however, no doubt that it was the Irish who made of this high-pitched, rudimentary instrument the harp which all the authors of the Middle Ages praised to the skies for Its strength and melodious tone. At that time it was esteemed superior to all other stringed instruments. This excellence developed thanks to an anterior column which permitted the increase in number and tautness of the strings.

The Celtic origins of the Occidental harp could equally well be proven by the fact that only the Celtic languages possess specific words for the harp's designation: Clarsaich in Irish and Scottish gaelic, Telyn in Welsh, Telenn in Breton. The first sure representation of the Celtic harp is rather late, on a cross of the Ullard Church near Kilkenny (830 a.d.), but it had probably existed long before this since this harp is a very refined model.

The most ancient specimen we possess, the Brian Born harp (Trinity College) dates from the 13th century. This bardic harp, with a height of 75cm, carries thirty or so brass strings. The harp was greatly cultivated and appreciated in Ireland, and the excellence of Ireland's musicians was acknowledged by all from the 12th to the 17th century.

The study of this instrument began at the age of ten. It was only at eighteen that one could be considered a professional. The harpist had to be master of three sorts of music: the "Suantraidhe," which none could hear without falling into a delicious sleep; the "Goltraidhe," which none could hear without bursting into tears; the "Genintraidhe," which none could hear without bursting out laughing.

All we know about the ancient technique is that it was played with sharpened nails, the execution being generally delicate and ornamental. The style was rich, light and rapid, sharpened arpeggios often played with fourth and fifth chords superimposed. Men or women of quality were rare who did not know how to play the harp.

The harpist was a person of high rank. "Three things which cannot be seized by course of justice," as the bardic triad goes, "the book, the harp and the sword" (irreplaceable measures of one's liberty).

On numerous occasions the harp seemed to be on the verge of disappearing, hunted out by the English occupiers, notably Cromwell, who had a great number destroyed. It was a subversive instrument exalting national sentiment. Its use in public was gradually restricted more and more to the blind and beggars. Nevertheless, up to the 18th century there continued to exist quite a number of popular harpists. The arrival of the harpsichord and later the piano accentuated the instrument's decline, which had begun with the disappearance of the nation's aristocracy. At the beginning of the 19th century a sudden rise in its favor gave birth to the Egan harp, which is the forefather of the Irish harp of today with gut and later nylon strings. However, the ancient tradition died with O'Daly and O'Carolan (who was already rather influenced by classical Italian music). There was a new revival in 1900, another at the founding of the Irish Republic, and even another during these last twenty years or so. This has resulted in a greater number of harpists and of thriving harp societies.

The Harp in Scotland and Wales — As early as the 5th century, Irish missionaries come to convert the Isle of Britain were in the habit of accompanying their psalms with a little harp. Scotland and Wales competed in their imitation of Irish music. The Scottish harp was identical to the Irish harp.

The Scottish bards and harpists did not survive the punitive measures following the 1715 and 1745 uprisings. The harp was completely supplanted by the bagpipes and the violin. During the last few years, we have witnessed a revival in the Scottish harp with the Comun Na Clarsaich Harpist Society. In Wales the harp followed its own evolution. From the Irish harp the Welsh, looking for chromatism, developed a large harp with three sets of strings. This overly difficult system has been more or less abandoned for a long time. Welsh harpists only use the Irish harp and, more especially, the classical Ehrard harp.

The Harp in Brittany — During the Breton immigration, missionaries from island Britain brought the harp to Armorica. Numerous representations from as early as the 11th century are known. In 1079, a charter given out in Nantes nominates a certain Cadiou as official harpist to Duke Hoel. In 1189 Richard the Lion Hearted called upon Breton harpists at the time of his coronation.

After having been an influential force throughout Europe (e.g., numerous stained glass windows, tapestries, or paintings where one can admire medieval harps derived from the Irish harp), the harp was to disappear when the Bretons lost their independence. It was abandoned, along with the language and the Breton culture, by the aristocracy fascinated by the French court. But this harp, which never ceased to ring out in the small baronial courts and at the festivals throughout the Middle Ages, was to remain alive in memory, ever more beautiful and evocative, perhaps because of having become exclusively a symbol of art, poetry, grace, purity and enchantment.

The Revival of the Celtic Harp

I had been preoccupied with the idea of reviving the Breton harp for a long time, but I could not see how to go about it since I had no practical knowledge of the craftsmanship of the instrument itself. The occasion presented itself for me to learn this during the Second World War and a period of enforced leisure in Clermont-Ferrand. I made the acquaintance of a harp teacher, a Breton like myself, J. M. Hamonic. who gave me some important information about the concert harp, which I then endeavored to transpose according to the applicable norms to instruments of which I only possessed graphic representations. In 1942 I undertook the construction, but I had to content myself with some preliminary efforts. It was not until well after the war, in Paris, that I was able to take up the work I had begun ten years before. I realized then that other people had also had the same idea, Herve Ar Menn, Taldir, among others, but nothing to my knowledge had been completed with the exception of a copy of an Irish harp made by a Paris firm.

At that time, I had already begun the construction of my first instrument from my own plans, and I had no desire to modify these after having seen and heard the results. It took more than a year's work during which I devoted all my leisure time before my "prototype" could be heard for the first time in public on the 28th of November, 1953, at the "Maison de Bretagne" under the fingers of my son Alan. From the prototype I made a further twenty or so for friends and also a few harps with metal strings which are known as bardic harps.

The Celtic harp once more holds a place of honor. In Brittany, in particular, the number of harpists now approaches one hundred. Everyone recognizes it as one of the family, to such an extent that it seems to many that it has never ceased to exist.

— Jord Cochevelou

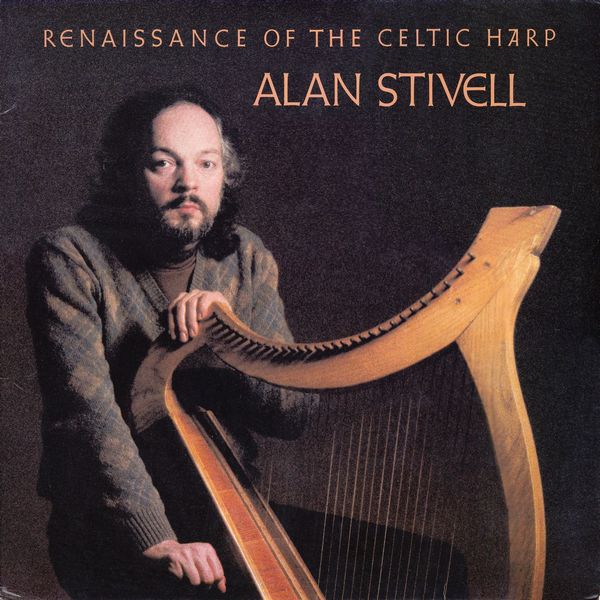

Alan Stivell Cochevelou

Alan's family comes from Gourin (lower central Brittany). They emigrated to Paris as did many from Gourin who did not leave for America. Born in 1944, Alan Stivell began to learn the piano at the age of five. His father soon put a harp at his disposal, which he began to learn immediately. Miss D. Megevand, concert harpist, directed his work for a number of years. His teacher and father mixed classical works with arrangements on folk themes from Brittany, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. He is the first for four centuries to make the Breton harp resonate again.

At the age of eleven, in short pants, he played at the Olympia, followed by the recording of two albums. To prevent his musical education from being either too superficial or too academic, he pushed his roots further into the popular music of the Celts, and into that of the Breton people in particular. With this goal in mind, and along with the harp, he studied traditional music, practicing the bombardon, the Scottish bagpipes (at the College of Piping in Glasgow). Under his direction the bagad Bleimor (the "bagad" in today's Breton language is a band of bombardons, bagpipes, and drums, inspired by the Scottish pipe band) was to play a leading role in the national bagadou competitions. His ideas, adopted by the bagad, have already made their mark on the evolution of Breton music with their synthesis of purity and authentic roots. Winning competitions for traditional music, Alan goes from town to town, fest-noz to fest-noz, making the old and the young dance, accompanied by Youenn Socard. That his ideas do not contradict a resolute modernism is shown in his diverse compositions and arrangements.

It is without doubt this double aspect of his background, at once classical and profoundly popular, which explains and has informed his musical approach recently. In 1965, while studying for a degree in English, with a strong specialty in Celtic, he began performing folk music accompanying himself on his harp (under the name Alan Stivell), and has brought Brittany to the eclectic world of contemporary music.

— Yann-Fanch Ar Merdy