|

|

|

| more images |

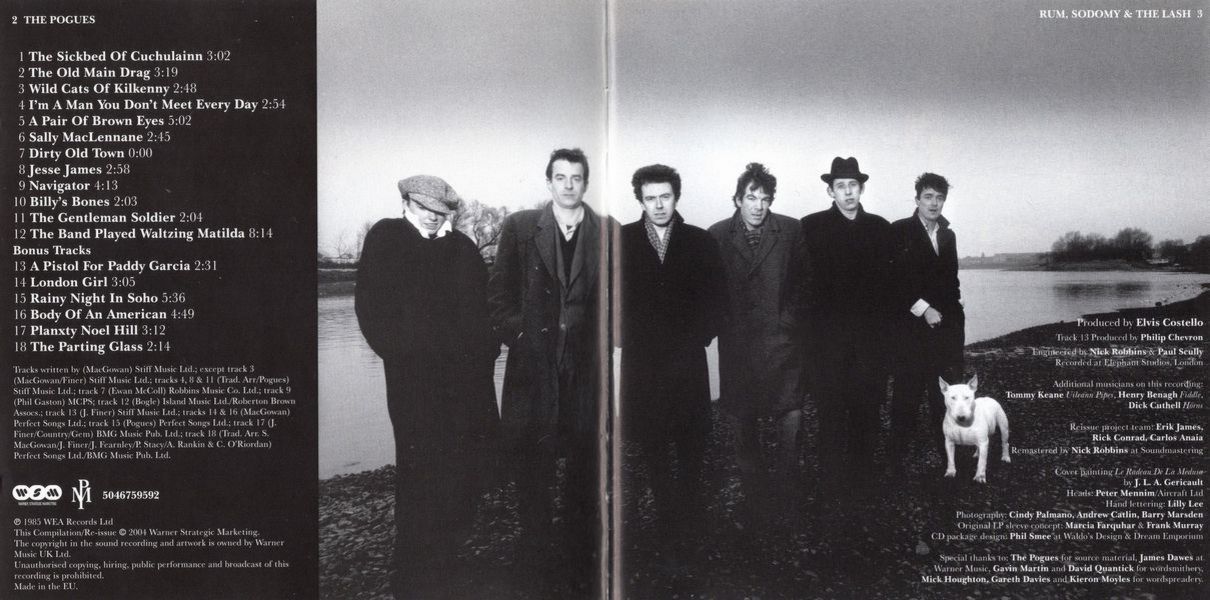

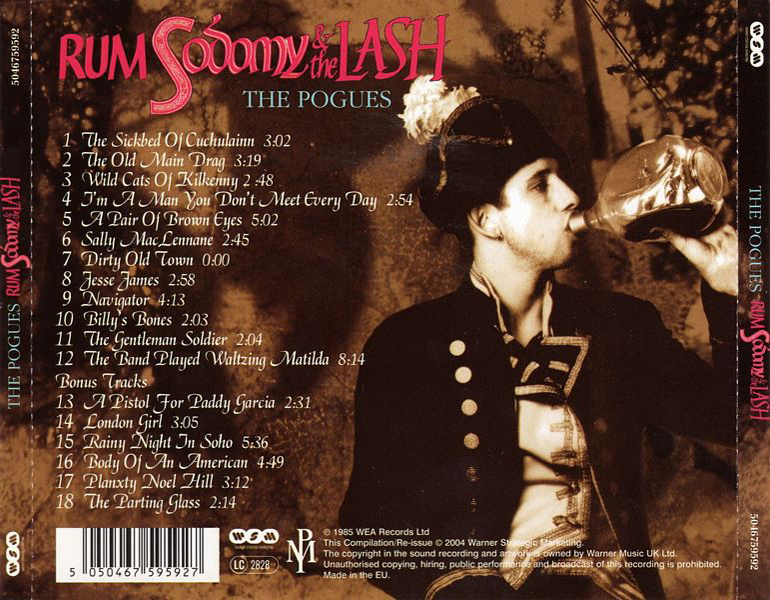

Sleeve Notes

In 1985, one of the most striking album launches of all time took place in London. It was a warm August night, and the venue, perhaps unwisely for an event involving enormous quantities of alcohol, was HMS Belfast.

The record being thus launched was the Pogues' second album, Rum Sodomy And The Lash, whose vaguely nautical theme inspired the band's PR Philip Hall to hire a battle cruiser.

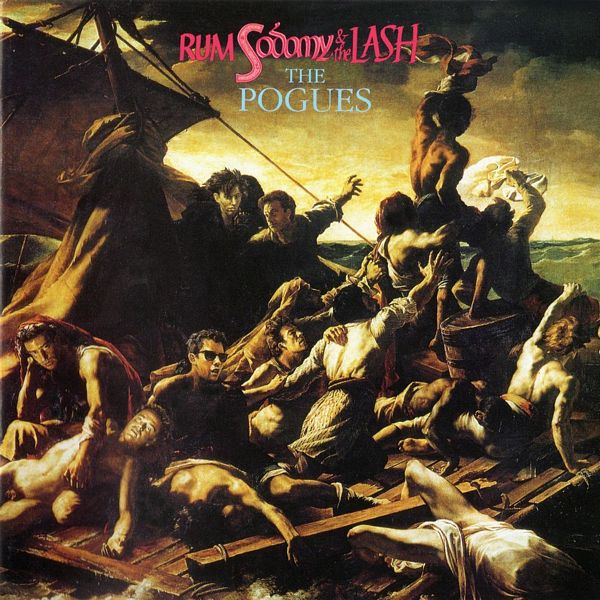

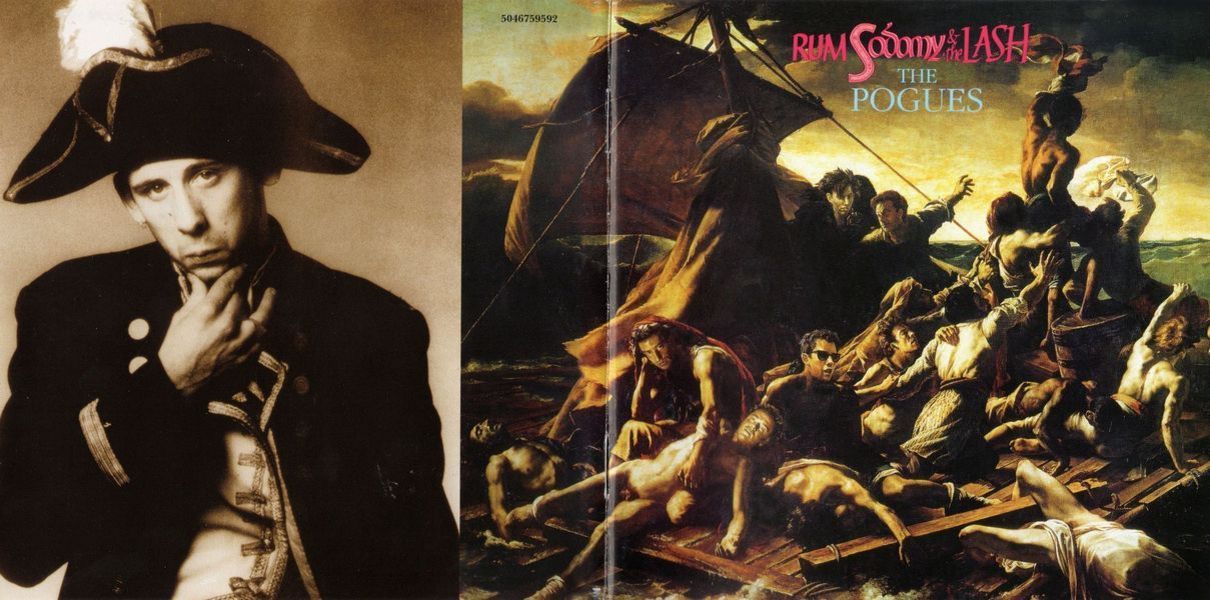

It made a kind of sense; while none of the band had ever been in the Navy, Rum Sodomy (as the record is generally called for short)'s title was taken from a quote by former Prime Minister and heavy drinker Winston Churchill — "Don't talk to me about naval tradition," said Mister Cigars, "It's nothing but rum, sodomy and the lash" — and featured a nautical ly-themed cover image. This was, as any Pogues fan or art historian will tell you, a reworking of the famous painting by Jean-Louis-Andre-Theodore Gericault, The Raft of the Medusa, completed in 1819, and altered in 1985 to feature the faces of the Pogues.

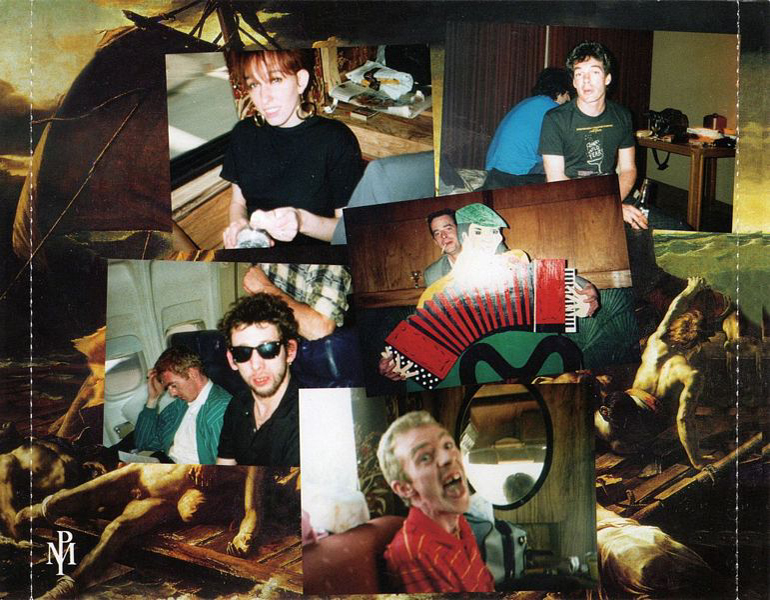

So the Navy and HMS Belfast, then. The band played in the Nelson-era naval costumes featured on the album's inner sleeve and journalists fought over the free drinks. Sometimes literally; one writer was actually thrown into the Thames. The admiral's hat worn by Shane MacGowan was never recovered. It was an extraordinary night, and one which launched the Pogues into the critical, if not the public eye.

Having established their actual existence with Red Roses For Me, the Pogues were now upping their game somewhat; their new single, 'A Pair Of Brown Eyes', was something of a major leap forward in both lyrical and song-writing terms. Dealing with the memories and current situation of a war veteran as he sat in a pub listening to country and Irish music, 'A Pair Of Brown Eyes' was not only long for a pop single, but featured both Shane MacGowan's best lyric to date — some might even say one of his all-time best — and an unusually thoughtful production. Rolling in on Andrew Rankin's drums and James Fearnley's organ, the song unfolds musically along with the lyric, and fades in a similarly bitter-sweet manner. Despite its low chart position — number 72 in the UK and nothing anywhere else — 'A Pair Of Brown Eyes' remains one of the high points of The Pogues' catalogue, and was the first of the band's records to make people think that they might not just be the soundtrack for a decent night in the pub.

There are two other interesting things about A Pair Of Brown Eyes'. One is that its video was directed, not by Stiff's usual video king Dave Robinson, who had brought TV fame to the likes of Pogues labelmates Madness and King Kurt, but by Alex Cox. Cox was at the time an extremely groovy cult movie director. He had just made Repo Man, one of the first great post-punk slacker movies. Cox was hired to direct the video after he had described the band as "quite interesting" in an interview. Or, as Shane would later explain, "We just read this interview where he said that he reckoned the Pogues were quite interesting, and we got together as soon as possible because we knew it would work because he's such a nutcase as well."

The result was not a conventional video at all, but rather a surreal and powerful collection of images, beginning with a tube train rounding a corner to the single's opening chord. It received little exposure, possibly because of Alex Cox's decision to interpret the song's title literally and feature two eyeballs in a paper bag, which get squashed at the end.

More commercially, and just as artistically, the producer of 'A Pair Of Brown Eyes' was Elvis Costello, himself a former Stiff Records signing and one of the most musically credible people around in 1985. Costello was also slated to produce the album. This was an immensely wise decision. As an artiste, Costello was on a creative high. As a producer, he was more of an unknown quantity, having produced only one other album. However, as that record was the debut album by The Specials, which had not only spawned several hit singles, but had also demonstrated an imaginative breadth of vision lacking from most of its contemporaries' work, nobody was particularly worried.

"I'm really looking forward to it, you know?" said Shane of the Costello/Pogues collaboration, "I'm not sure just how big an effect he is going to have on how it turns out, because we already know it is going to be quite different from the first one... I don't that means it will necessarily be any cleaner or more professional, because one of the numbers on it will be the fastest thing we have ever done, and a couple of the others are fairly rough as well. You'll still know it's the Pogues."

Meanwhile, Costello was becoming a major champion of the band. He took them out as tour support in Ireland. This was at some potential cost to his own career. ("On the Elvis Costello tour," James Fearnley once said, "We only had to play for half an hour, and you could go drink yourself stupid afterwards because we had no responsibilities"), and he supported them himself when the band played the Clarendon Hotel on their first major St Patrick's Day concert. Backstage, Caitlin O'Riordan revealed that the band's nickname for their new producer was "Uncle Brian". (Later, the world would come to know Cait as "Mrs Elvis Costello", but that's another story).

The concert took place in a break from the Rum Sodomy sessions. The first fruit of those sessions came out in June. 'Sally MacLennane', with its thunderous drum intro — reminiscent of the explosive rim shots all over that first Specials album — was the first Pogues single to be nearly a hit. You could also get it in — what else but — green vinyl.

When Rum, Sodomy And The Lash was released in August of that year, it was an instant critical success. Costello's production was noted, as was MacGowan's songwriting. Little was said at the time about the presence of additional musicians; one of these essential contributors to the new Pogues sound was Philip Chevron. Born Philip Ryan in Dublin, Chevron was a member of Irish punk band The Radiators From Space. He had produced the debut single by 'The Men They Couldn't Hang' — a band who were not only called after a rejected Pogues name but had as their bass player Shane's former Nips cohort Shanne Bradley, and had recently released a superb single, a version of the Brendan Behan song 'The Captains And The Kings', produced by Elvis Costello. Why, he was virtually in the Pogues by osmosis. (Chevron had also toured with the band as a temporary replacement for Jem Finer. Then, after Shane decided he wanted to be able to sing without having to play the guitar, Chevron became a proper Pogue.)

"I saw my task was to capture them in their dilapidated glory before some more professional producer fucked them up," Elvis Costello was to say later, but this modesty belies both his own contributions to the record — a new, three dimensional quality, and a particular imaginative sense that a more conventional producer might have lacked — and those of the band. This was, after all, a group who had inspired no less a man in a hat who wrote songs about drink and love than Tom Waits to ask a journalist, "Have you heard of the Pogues? They're like a drunk Clancy Brothers. They, like drink during the session as opposed to after the session. They're like Dead End Kids on a leaky boat. That Treasure Island kind of decadence. There's something really nice about them."

"Nice" is not a word that precisely describes Rum, Sodomy And The Lash (although "Dead End Kids on a leaky boat" is pretty close). It is an extraordinary record. For a start, the band's background comes to the fore from every direction. These days, "punk folk" is a horrible expression that generally just means either people with banjos playing Clash songs or people with guitars playing folk songs badly. The Pogues took on both their folk roots and their own punk pasts and made something completely new. The opening pair of tracks, 'The Sick Bed Of Cuchulain' and 'The Old Main Drag', are perfect, if contrasting examples (and they would have been a great double A-side single). The first is a hundred mile an hour rant that would have worked perfectly well in the old Pogue Mahone pub days, but its subject matter is, loosely, one of the legendary kings of old Ireland — or, to quote Shane, "He's one of the most famous Irish mythical figures. He's like Finn McCool. He was the champion." And the second is a classic tale of London youth, the abused rent boy in Piccadilly. 'The Old Main Drag' is punk in every way except one; its setting, which is the slow drone of the uillean pipe with accompanying banjo.

The album's themes are remarkable, too. In an era when popular music was either cheerful or Morrissey, MacGowan's lyrics are neither happy nor insular. They are, however, fixated around death. Nearly every song mentions, or features death. (When this was pointed out to the band, Spider Stacey remarked, truthfully, that the journalist had left out the instrumental, 'The Wild Gats Of Kilkenny', which is also about death). From 'A Pair Of Brown Eyes' fatalism to the surreal, Cait-sung 'I'm A Man You Don't Meet Everyday', this is a fatalistic vision.

It's also a hilarious one, too. Cuchulain dies, but he leaps out of his coffin at the end. 'Billy's Bones' is absurd and 'Sally MacLennane' is just manic. And it features at least one real character, the "elephant man" who "broke strong men's necks when he had too many Powers". Shane explained, "The Elephant man in that song was a real bloke, who was a huge bloke and he used to get into terrible fights... and one night he got into a fight with another huge bastard and he won the fight, but he got a broken neck in the process. And he went around with a cast around his neck, which is why they called him the elephant man." So now you know.

Special mention must be given to the album's two covers — the superb 'Navigator', written by Phil Gaston, band friend and musician, and Ewan McColl's 'Dirty Old Town'. King folkie McColl at first disliked the Pogues' version of his standard, but later sensibly changed his mind. Later, of course, his daughter Kirsty would help make one Pogues song a standard in its own right.

But the real legacy of Rum, Sodomy and the Lash is that it gave a new vitality to the music it came from. Not, of course, that everyone was happy.

"When we put out the second album," Phil Chevron once said, "we had a press conference in Dublin, where there was a certain group of people who were opposed to whatever we were trying to do because we were plastic paddies. We had people who just challenged the whole thing from the fore of the press conference. 'What you are doing is bastardising Irish music'."

But all that was about to change forever. For now, people who had never grown up with folk music suddenly discovered Irish roots. People who had associated the accordion and banjo with dull family weddings found new life in old songs. Live music became exciting once more. And nobody would ever be bored by a banjo again.

David Quantick