|

|

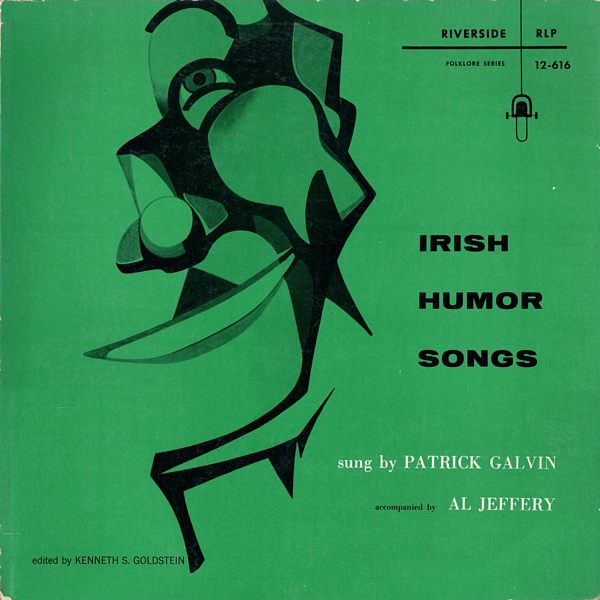

Sleeve Notes

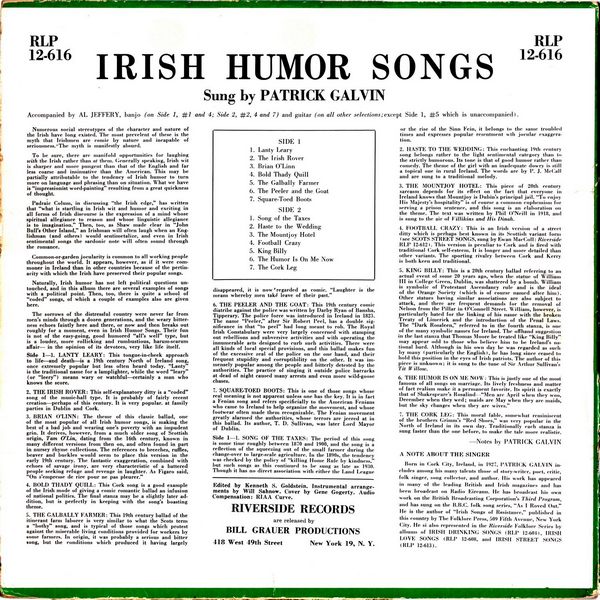

Numerous social stereotypes of the character and nature of the Irish have long existed. The most prevelent of these is the myth that Irishmen are comic by nature and incapable of seriousness. The myth is manifestly absurd.

To be sure, there are manifold opportunities for laughing with the Irish rather than at them. Generally speaking, Irish wit is sharper and more pungent than that of the English and far less coarse and insinuative than the American. This may be partially attributable to the tendency of Irish humor to turn more on language and phrasing than on situation. What we have is "impressionist word-painting" resulting from a great quickness of thought.

Padraic Colum, in discussing "the Irish edge," has written that "what is startling in Irish wit and humor and exciting in all forms of Irish discourse is the expression of a mind whose spiritual allegiance to reason and whose linguistic allegiance is to imagination." Then, too, as Shaw made clear in "John Bull's Other Island," an Irishman will often laugh when an Englishman (and others) would sentimetalize, and even in Irish sentimental songs the sardonic note will often sound through the romance.

Common-or-garden jocularity is common to all working people throughout the world. It appears, however, as if it were commoner in Ireland than in other countries because of the pertinacity with which the Irish have preserved their popular songs.

Naturally, Irish humor has not left political questions untouched, and in this album there are several examples of songs with a political point. Then, too, there is quite a school of "coded" songs, of which a couple of examples also are given here.

The sorrows of the distressful country were never far from men's minds through a dozen generations, and the weary bitterness echoes faintly here and there, or now and then breaks out roughly for a moment, even in Irish Humor Songs. Their fun is not of the easy-going, good humored "all's well" type, but is a louder, more rollicking and rumbustious, harum-scarum affair — in the opinion of its devotees, very like life itself.

LANTY LEARY: This tongue-in-cheek approach to life — and death — is a 19th century North of Ireland song, once extremely popular but less often heard today. "Lanty" is the traditional name for a lamplighter, while the word "leary" (or "leery") means wary or watchful — certainly a man who knows the score.

THE IRISH ROVER: This self-explanatory ditty is a "coded" song of the music-hall type. It is probably of fairly recent creation — perhaps of this century. It is very popular, at family parties in Dublin and Cork.

BRIAN O'LINN: The theme of this classic ballad, one of the most popular of all Irish humor songs, is making the best of a bad job and wearing one's poverty with an impudent grin. It derives, however, from a much older song of Scottish origin, Tam O'Lin, dating from the 16th century, known in many different versions from then on, and often found in part in nursey rhyme collections. The references to breeches, ruffles, beaver and buckles would seem to place this version in the early 19th century. The fantastic exaggeration, combined with echoes of savage irony, are very characteristic of a battered people seeking refuge and revenge in laughter. As Figaro said, "On s'empresse de rire pour ne pas pleurer."

BOLD THADY QUILL: This Cork song is a good example of the Irish mode of giving a comic romantic ballad an infusion of national politics. The final stanza may be a slightly later addition, but is perfectly in keeping with the song's boasting theme.

THE GALBALLY FARMER: This 19th century ballad of the itinerant farm laborer is very similar to what the Scots term a "bothy" song, and is typical of those songs which protest against the miserable living conditions provided for workers by some farmers. In origin, it was probably a serious and bitter song, but the conditions which produced it having largely disappeared, it is now regarded as comic. "Laughter is the means whereby men take leave of their past."

THE PEELER AND THE GOAT: This 19th century comic diatribe against the police was written by Darby Ryan of Bansha, Tipperary. The police force was introduced in Ireland in 1823. The name "Peeler," after Sir Robert Peel, has a double significance in that "to peel" had long meant to rob. The Royal Irish Constabulary were very largely concerned with stamping out rebellions and subversive activities and with operating the innumerable acts designed to curb such activities. There were all kinds of local special provisions, and this ballad makes fun of the excessive zeal of the police on the one hand, and their frequent stupidity and corruptibility on the other. It was immensely popular among the people and bitterly detested by the authorities. The practice of singing it outside police barracks at dead of night caused many arrests and even more wild-goose chases.

SQUARE-TOED BOOTS: This is one of those songs whose real meaning is not apparent unless one has the key. It is in fact a Fenian song and refers specifically to the American Fenians who came to Ireland to help organize the movement, and whose footwear often made them recognizable. The Fenian movement greatly alarmed the authorities, whose terrors are jeered at in this ballad. Its author, T. D. Sullivan, was later Lord Mayor of Dublin.

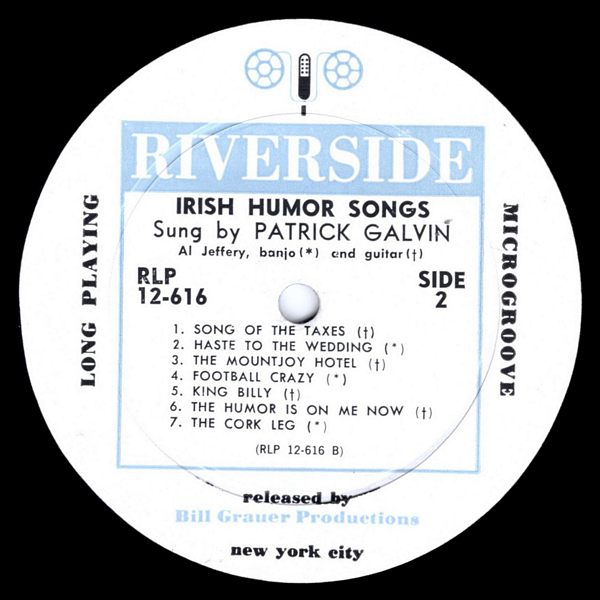

SONG OF THE TAXES: The period of this song is some time roughly between 1870 and 1900, and the song is a reflection of the squeezing out of the small farmer during the change-over to large-scale agriculture. In the 1890s. the tendency was checked by the policy of "killing Home Rule by kindness," but such songs as this continued to be sung as late as 1930. Though it has no direct association with either the Land League or the rise of the Sinn Fein, it belongs to the same troubled times and expresses popular resentment with jocular exaggeration.

HASTE TO THE WEDDING: This enchanting 19th century song belongs rather to the light sentimental category than to the strictly humorous. Its tone is that of good humor rather than comedy. The theme of the girl with an inadequate dowry is still a topical one in rural Ireland. The words are by P. J. McCall and are sung to a traditional melody.

THE MOUNTJOY HOTEL: This piece of 20th century sarcasm depends for its effect on the fact that everyone in Ireland knows that Mountjoy is Dubin's principal jail. "To enjoy His Majesty's hospitality" is of course a common euphemism for serving a prison sentence, and this song is an elaboration on the theme. The text was written by Phil O'Neill in 1918, and is sung to the air of Villikins and His Dinah.

FOOTBALL CRAZY: This is an Irish version of a street ditty which is perhaps best known in its Scottish variant form (see SCOTS STREET SONGS, sung by Ewan MacColl: Riverside RLP 12-612). This version is peculiar to Cork and is fired with traditional Cork self-esteem. It is longer and more detailed than other variants. The sporting rivalry between Cork and Kerry is both keen and traditional.

KING BILLY: This is a 20th century ballad referring to an actual event of some 20 years ago, when the statue of William III in College Green, Dublin, was shattered by a bomb. William is symbolic of Protestant Ascendancy rule and is the ideal of the Orange Society (which is of course named after him). Other statues having similar associations are also subject to attack, and there are frequent demands for the removal of Nelson from the Pillar in O'Connell Street. William, however, is particularly hated for the linking of his name with the broken Treaty of Limerick and the introduction of the Penal Laws. The "Dark Rosaleen," referred to in the fourth stanza, is one of the many symbolic names for Ireland. The offhand suggestion in the last stanza that Thomas Moore be treated like "King Billy" may appear odd to those who believe him to be Ireland's national bard. Although in his own day he was regarded as such by many (particularly the English), he has long since ceased to hold this position in the eyes of Irish patriots. The author of this piece is unknown; it is sung to the tune of Sir Arthur Sullivan's Tit Willow.

THE HUMOR IS ON ME NOW: This is justly one of the most famous of all songs on marriage. Its lively freshness and matter of fact realism make it a permanent favorite. Its spirit is exactly that of Shakespeare's Rosalind—"Men are April when they woo, December when they wed; maids are May when they are maids, but the sky changes when they are wives."

THE CORK LEG: This moral fable, somewhat reminiscent of the brothers Grimm's "Red Shoes," was very popular in the North of Ireland in its own day. Traditionally each stanza is sung faster than the one before, to make the tale more realistic.

— Notes by PATRICK GALVIN

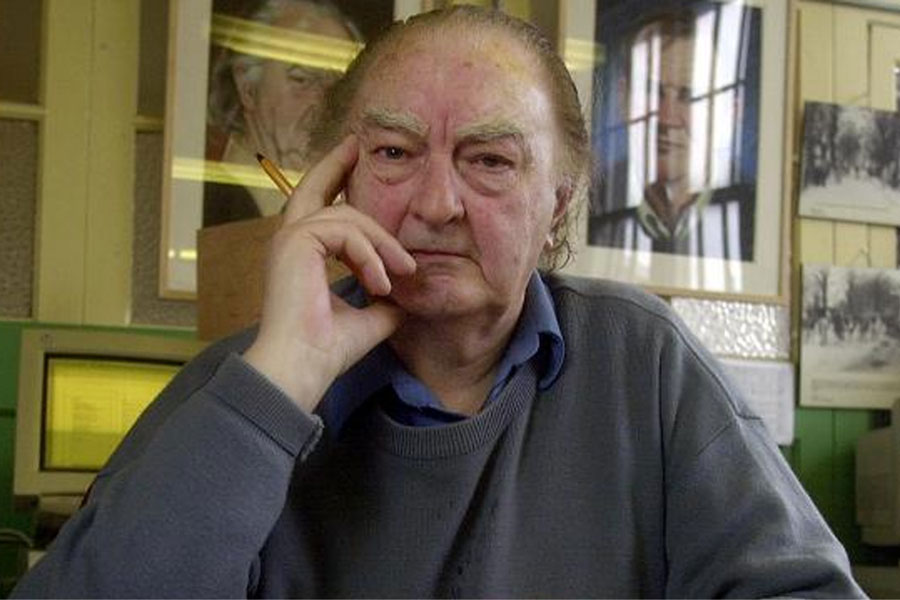

A Note About the Singer

Born in Cork City, Ireland, in 1927, PATRICK GALVIN includes among his many talents those of story-writer, poet, critic, folk singer, song collector, and author. His work has appeared in many of the leading British and Irish magazines and has been broadcast on Radio Eireann. He has broadcast his own work on the British Broadcasting Corporation's Third Program, and has sung on the B.B.C. folk song series, "As I Roved Out." He is the author of "Irish Songs of Resistance," published in this country by The Folklore Press, 509 Fifth Avenue, New York City. He is also represented in the Riverside Folklore Series by albums of IRISH DRINKING SONGS (RLP 12-604), IRISH LOVE SONGS (RLP 12-608, and IRISH STREET SONGS (RLP 12-613).