|

|

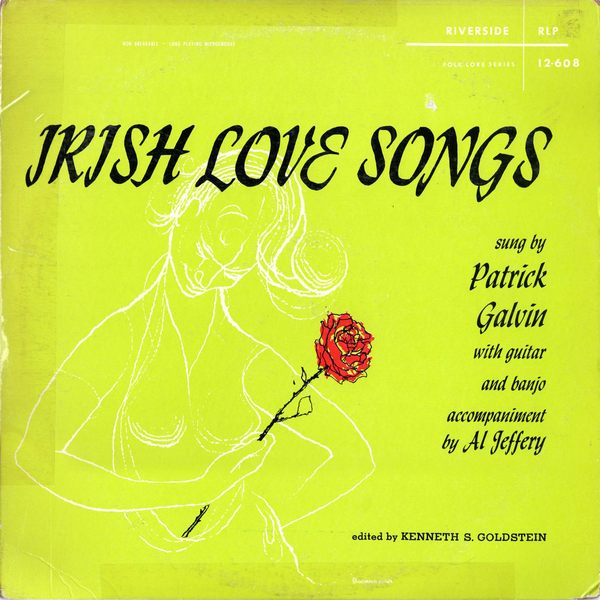

Sleeve Notes

"From the cradle to the grave the Irishman's life is set to music. It begins with the lullabies of infancy; keening ends it when the spirit leaves the body. Work has its songs as well as play; there are lovesongs and dances, and never are the songs so beautiful as when the lover is the poet." *

The above quotation is only one of numerous equally laudatory comments concerning the beauty of Irish love songs made by non-Irish (and nationalistically unconcerned) critics. And there is good reason for this, for Irish love songs have had a many centuries long tradition of both musical and textual beauty. The Gaelic bards and minstrels, the blind harpers, and the Irish peasantry have all contributed to the creation and circulation of love songs of unusual grace and charm. Though the Gaelic tongue, the original language of their composition, is in little use today, the musical strain and metrical form of Gaelic love songs can still be heard in some of the Anglo-Irish love songs and ballads found in this album.

There are those critics, both Irish and non-Irish, who would deprecate most, if not all, of Anglo-Irish song. To them, the poetry is of an inferior order, and the music is, at best, second-rate. This album is not intended as an answer to these critics; rather, it is intended to present, for purposes of entertainment only, an excellent cross-section of the many varied kinds of Irish love songs.

— K.S.G.

*Redfern Mason, "The Songlore of Ireland," The Biker & Taylor Co., N. Y., 1911. (The italics in the quotation are mine — K.S.G.)

In general, Irish love songs are very hard to localize. Most of them are known and sung all over Ireland with very little local variation in either text or music. A few of them are versions of songs current all over the British Isles. Many of them are translations from the Gaelic.

Almost all Irish love songs are women's songs. The airs, often of extraordinary and haunting beauty, are usually of a melancholy nature. The melancholy strain — "O what can women do but weep" — is natural enough in a country that saw the flower of its young manhood wiped out in battle or by exile generation after generation for centuries.

Practically all Irish love songs are narrative or have a strong narrative element. There are hardly any (except a few translations from the Gaelic) of the type whose purpose is to glorify the charms of the beloved. A great many of them might equally well be classified as national or "rebel" songs, and indeed it is often a Solomon's Judgement to decide which way to classify them. Many are gently humorous or teasing, but the vigorous bawdy strain so common in much folk song elsewhere is conspicuously lacking in Ireland.

There are a good many apparent love songs which are in fact concealed or "code" political songs, in which, for example, a woman's name stands for Ireland or a song-bird represents the exiles, although the face value of the words completely sustains the illusion of a normal love song. This tradition of cryptic ballads dates from the time of the Penal Laws (17th and 18th cenutry), when any sort of Irishism — in speech, dress, custom or belief — was punishable by heavy penalties, even death. In the Penal times people were literally hanged "for wearing of the green". From those days also dates the Irish traditional method of singing solo (choral singing is virutally unknown), unaccompanied, and very softly, since assemblies of people were forbidden and attracting attention was very dangerous.

I KNOW WHERE I'M GOING: This is one of the most famous of the Irish love songs from a Gaelic tradition. Herbert Hughes reported a similar version from County Antrim in Volume I of his "Irish Country Songs." It is equally well known in Scotland in several variant forms. One Scotch variant has almost identical music and text; a second version, less frequently heard, goes by the name The Licht Bob's Lassie. The expression "the dear knows" (in the first stanza) is the Ulster equivalent of "goodness only knows."

MY LOVE CAME TO DUBLIN: This relatively modern love song retells one of the oldest stories concerning womankind's most frequent cause for lamentation. Here is the "summer romance" and "careless love" so often the subject of folk song. The tune is a close variant of Haste to the Wedding and The Bold Thady Quill, but of a different tempo.

CANADA IHO: Although the text of this ballad has no Irish content whatever, it is quite commonly heard all over Ireland. The name of the mythical city "Canada Iho" would seem to be a mixture of Canada, Idaho, Chicago and Ohio. The song was known in the United States in the early part of the 19th century, having appeared in several songsters of the day. The American lumberjack ballad Canaday I-O is believed to be an adaptation by a Maine lumberman of Canada Iho, which was known in Maine through the wide circulation of "The Forget Me Not Songster" (For a comparison of this song with the lumberjack ballad, see Ed McCurdy's recording of Canaday I-O on THE BALLAD RECORD, Riverside RLP 12-601.)

BRIAN OG AND MOLLY BAN: A light song of a teasing kind, this ballad is very characteristic of light hearted Irish humor. It is an interesting example of the Anglo-Irish ballad in that it has a fair sprinkling of Gaelic expressions throughout the text as well as in it* title. The translation of the title reads: Young Brian and Fair Molly. "A chara" in the third stanza means "my dear", and the expression "Gradh mo croidhe, a storin" can be translated as "Love of my heart, my darling". This song is a dialogue and, strictly speaking, should be sung as a duet; however, it is commonly rendered as a solo by both male and female singers. It dates from the early 19th century, when the Anglo-Irish ballad was coming into fairly commonplace usage.

THE BONNY BOY: The Irish version of this popular traditional ballad is more elaborate and romantic than its British counterparts. First published as Lady Mary Ann in Johnson's "Scots Musical Museum" in 1792. the ballad is believed to be based on a true incident. In 1631 Sir Robert Innes obtained the guardianship of the young Lord Craigton to whom he shortly thereafter married his daughter, Elizabeth. The young husband died three years later. The ballad spread from Scotland to England (and from there to Ireland and America at a later date.) In the course of time, it lost all of its local references. The mention of "a ribbon blue" refers to the common folk custom of wearing a colored ribbon as a marriage favor.

THE BANKS OF THE ROSES: Here is a pretty example of the "take me as you find me" love song, common in most folk balladry. This Limerick song dates from the end of the 18th century. Versions have been collected in both England and Scotland. In Colm O Lochlainn's "Irish Street Ballads," a version almost identical to this one can be found.

THE WIND THAT SHAKES THE BARLEY: This 19th century composed song, with its haunting melody, is one of the most beautiful of all Irish love songs. It describes an imaginary, but typical, incident of the Great Rebellion of 1798. It was written by Robert Dwyer Joyce, a member of the Fenian Brotherhood who was forced to leave Ireland for the United States when in danger of arrest for nationalist activities. It is sung to the tune Royal Charley.

SHULE AROON: This is perhaps the finest of all Irish songs of the lament type. An 18th century version of a Gaelic ballad, it refers to the lover's enlistment among the "Wild Geese" of the Irish Brigade in the service of France. It was the hope of these brave Irish heroes that they would some-day return to drive the British out of their homeland. Inumerable versions have been collected in Ireland, as well as in Scotland and America. The Scottish Shule Agra is a later version to a much more jocular air. In America, the song has come down as Johnny Has Gone For A Soldier. The translation of the Gaelic refrain has been versified by Dr. Sigerson as follows:

Come, come, come, oh love!

Quickly come to me, softly move;

Come to the door and away we'll flee,

And safe for aye may my darling be.

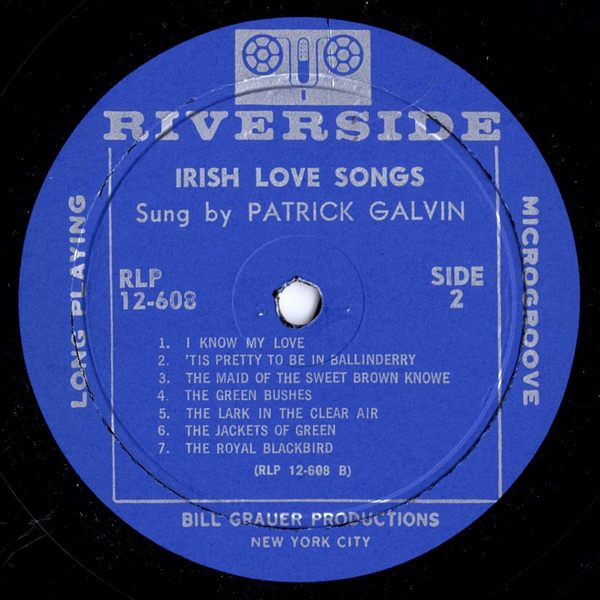

I KNOW MY LOVE: This is one of the most popular songs in Ireland and is sung to a traditional air which is of a rather more complex kind than is usual. In "Irish Country Songs," Volume I, Herbert Hughes informs us that this is an old song which, in certain parts of Ireland, was sung in alternating verses of Gaelic and English.

'TIS PRETTY TO BE IN BALLINDERRY: This north of Ireland song, notable for its delightful melody, is of the familiar lamentation type. The wail Och anee is sung as a reminiscent, melancholy lament, rather than as an exclamation of grief, though we can be sure that the sweetheart's loss has been softened only slightly by the passage of time.

THE MAID OF THE SWEET BROWN KNOWE: This 19th century song, mainly sung in the North, is usually performed unaccompanied. The story is an unusual one for Irish song in that the self-possessed young lady remains unimpressed by romantic protestations, and has the tables turned on her by the young man whose romanticism was only for show after all. A "knowe" is a little hill.

THE GREEN BUSHES: This song has been as frequently reported in England as in Ireland and a great deal of conjecture has arisen as to its origin. Verses of this song were incorporated in Buckstone's play "Green Bushes," and it has been suggested that it originated there. Another theory is that it is a version of an earlier ballad Whitsun Monday, or perhaps of Low Down in the Broom. In explaining his belief that the melody was not Irish, Baring-Gould wrote: "... a good many of the so-called Irish melodies, to English words, are English that have been carried to Ireland by the soldiers quartered there." In any case, the song is very popular today among street singers in Cork.

THE LARK IN THE CLEAR AIR: This composed song is included for its beauty and musical interest. It is extremely popular and very widely sung in Ireland, in spite of the nature of the air which is more elaborate and complex than that of other popular songs. The words to this beautiful song were written by Samuel Ferguson, the great 19th century Irish poet, translator, and antiquarian.

THE JACKETS OF GREEN: This late 19th century composed song is one of many written during the Young Ireland and Fenian movements to publicize gallant exploits in past Irish history. It describes events of the late 17th century, when Ireland was divided between Catholic supporters of the deposed Stuart, James II, and the Protestant supporters of William II. This ballad is but one of many Irish love songs based on political events and national struggles. The text was written by Michael Scanlan, who was also the author of the famous marching song, The Bold Fenian Men.

THE ROYAL BLACKBIRD: Here is a notable example of the "coded" love song. The Blackbird represents the exiled house of Stuart — James II and his son (the Old Pretender) and grandson (the Young Pretender). There are a number of variants to the words and it is sometimes sung to a slightly different air. It was a favorite song in Scotland during and after the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715, and this led to the claim of its possible Scottish origin. But in his "Lyrics of Ireland," Samuel Lover wrote, concerning this song, that its "Hibernian origin . . . cannot be questioned for a moment by anyone familiar with the phraseology and peculiar structure of Anglo-Irish songs. The air, moreover, to which it is sung is given in Bunting's last collection." Few scholars today question its Irish origin.

— Notes by PATRICK GALVIN

A NOTE ABOUT THE SINGER

Born in Cork City, Ireland, in 1927, PATRICK GALVIN includes among his many talents those of poet, critic, folk singer, song collector and author. His work has appeared in many of the leading British and Irish magazines and has been broadcast on Radio Eireann. He has broadcast his own work on the British Broadcasting Corporation's "Third Programme" and has sung on the B.B.C. folk song series, "As I Roved Out." He is the author of "Irish Songs of Resistance," published by the Folklore Press, 509 Fifth Avenue, New York City. He can also be heard on Riverside in an album of

IRISH DRINKING SONGS (RLP 12-604).