|

|

|

Sleeve Notes

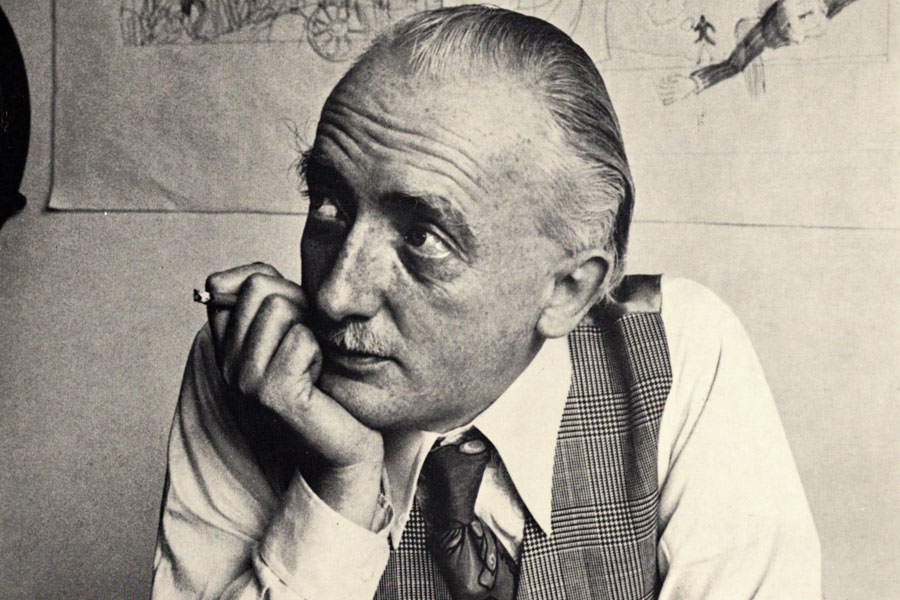

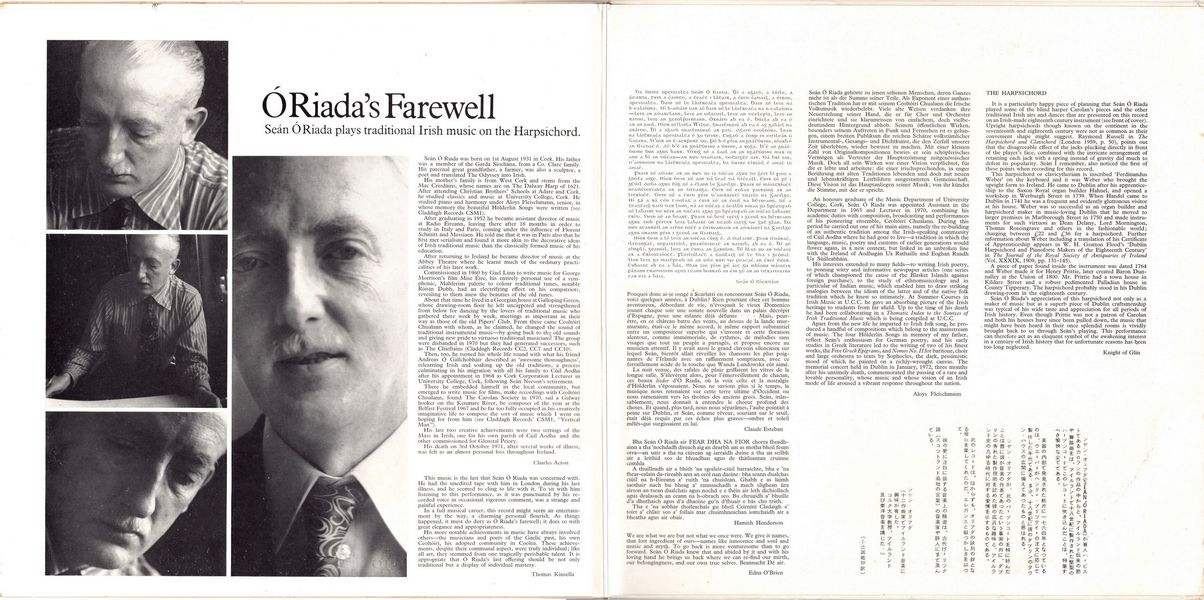

Seán Ó Riada was born on 1st August 1931 in Cork. His father was a member of the Garda Siochána, from a Co. Clare family. His paternal great-grandfather, a farmer, was also a sculptor, a poet and translated The Odyssey into Irish.

His mother's family is from West Cork and stems from the Mac Críodáins, whose names are on The Dalway Harp of 1621. After attending Christian Brothers' Schools at Adare and Cork, he studied classics and music at University College, Cork. He studied piano and harmony under Aloys Fleischman., senior, in whose memory the beautiful Hölderlin Songs were written (see Claddagh Records CSM1).

After graduating in 1952 he became assistant director of music at Radio Eireann, leaving there after 18 months in order to study in Italy and Paris, coming under the influence of Florent Schmitt and Messiaen. He told me that it was in Paris also that he first met serialism and found it more akin to the decorative ideas of Irish traditional music than the classically formed music of his education.

After returning to Ireland he became director of music at the Abbey Theatre where he learnt much of the ordinary practicalities of his later work.

Commissioned in 1960 by Gael Linn to write music for George Morrison's film Miss Éire, his entirely personal use of a symphonic, Mahlerian palette to colour traditional tunes, notably Róisín Dubh, had an electrifying effect on his compatriots, revealing to them anew the beauties of the old tunes.

About that time he lived in a Georgian house at Galloping Green, whose drawing-room floor he left uncarpeted and strengthened from below for dancing by the lovers of traditional music who gathered there week by week, meetings as important in their way as those of the old Pipers Club. From these came Ceoltóirí Chualann with whom, as he claimed, he changed the sound of traditional instrumental music — by going back to the old sounds and giving new pride to virtuoso traditional musicians. The group were disbanded in 1970 but they had generated successors, such as The Chieftains (Claddagh Records CC2, CC7, CC10 and CC14).

Then, too, he turned his whole life round with what his friend Andreas Ó Gallchoir described as `awesome thoroughness', relearning Irish and soaking up the old traditions, a process culminating in his migration with all his family to Cúil Aodha after his appointment in 1964 as Cork Corporation Lecturer in University College, Cork, following Seán Neeson's retirement. There he embedded himself in the local community, but emerged to write music for films, make recordings with Ceoltóirí Cualann, found The Carolan Society in 1970, sail a Galway hooker on the Kenmare River, be composer of the year at the Belfast Festival 1967 and be far too fully occupied in his creatively imaginative life to compose the sort of music which I went on hoping for from him (see Claddagh Records CSM1, 'Vertical Man'). His last two creative achievements were two settings of the Mass in Irish, one for his own parish of Cúil Aodha and the other commissioned for Glenstal Priory.

His death on 3rd October 1971, after several weeks of illness was felt as an almost personal loss throughout Ireland.

Charles Acton

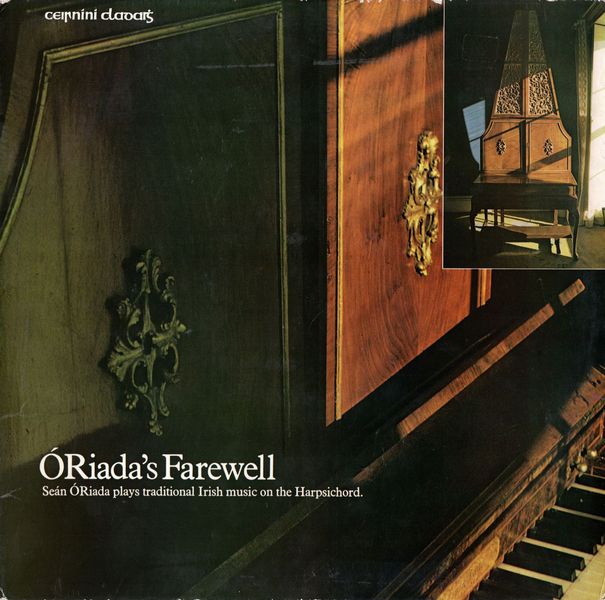

This music is the last that Seán Ó Riada was concerned with. He had the unedited tape with him in London during his last illness, and he seemed to ding to life with it. To sit with hits listening to this performance, as it was punctuated by his recorded voice in occasional vigorous comment, was a strange and painful experience.

In a full musical career, this record might seem an entertainment by the way, a charming personal flourish. As things happened, it must do duty as Ó Riada's farewell; it does so with great elegance and appropriateness.

His more notable achievements in music have always involved others — the musicians and poets of the Gaelic past, his own Ceoltóirí, his adopted community in Coolea. These achievements, despite their communal aspect, were truly individual; like all art, they stemmed from one tragically perishable talent. It is appropriate that Ó Riada's last offering should be not only traditional but a display of individual mastery.

Thomas Kinsella