|

|

|

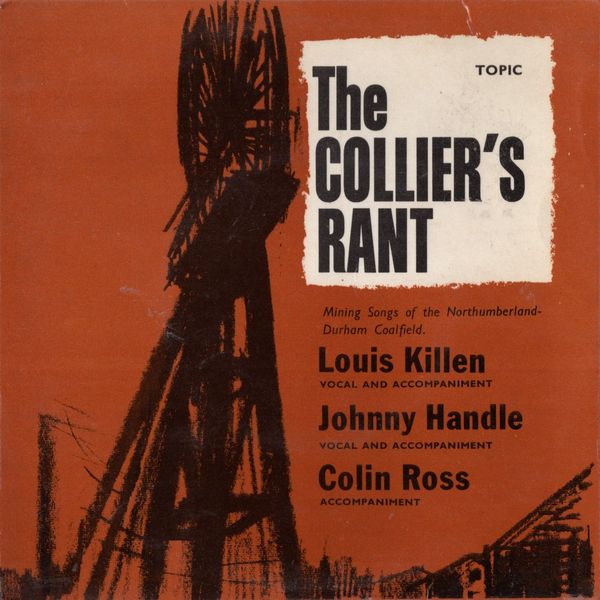

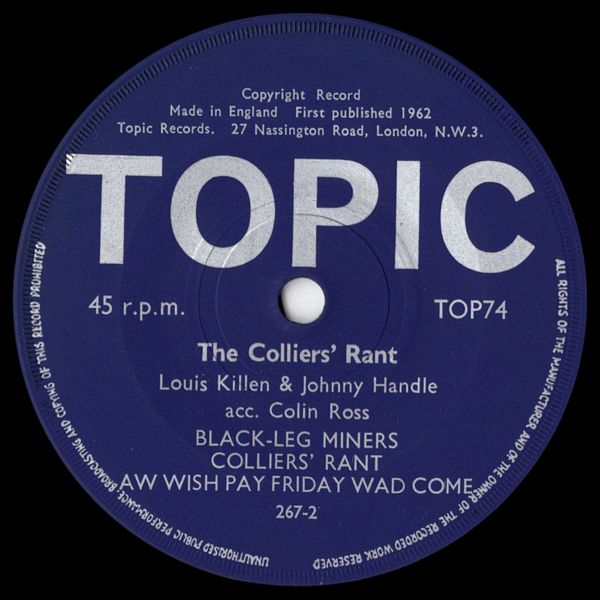

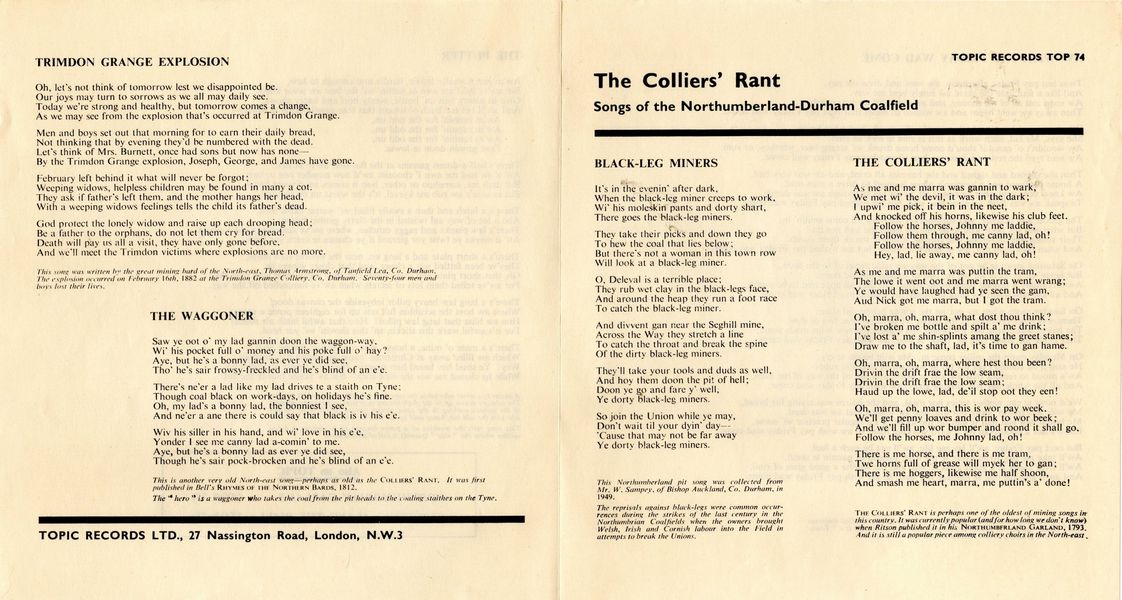

Sleeve Notes

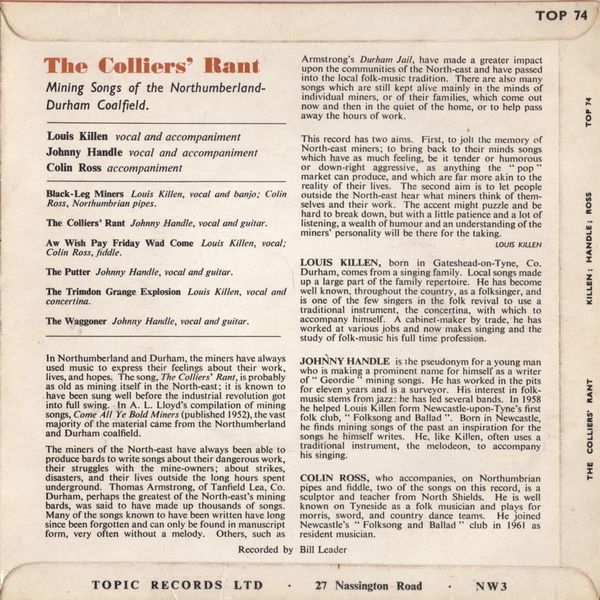

In Northumberland and Durham, the miners have always used music to express their feelings about their work, lives, and hopes. The song, The Colliers' Rant, is probably as old as mining itself in the North-east; it is known to have been sung well before the industrial revolution got into full swing. In A. L. Lloyd's compilation of mining songs, Come All Ye Bold Miners (published 1952), the vast majority of the material came from the Northumberland and Durham coalfield.

The miners of the North-east have always been able to produce bards to write songs about their dangerous work, their struggles with the mine-owners; about strikes, disasters, and their lives outside the long hours spent underground. Thomas Armstrong, of Tanfield Lea, Co. Durham, perhaps the greatest of the North-east's mining bards, was said to have made up thousands of songs. Many of the songs known to have been written have long since been forgotten and can only be found in manuscript form, very often without a melody. Others, such as Armstrong's Durham Jail, have made a greater impact upon the communities of the North-east and have passed into the local folk-music tradition. There are also many songs which are still kept alive mainly in the minds of individual miners, or of their families, which come out now and then in the quiet of the home, or to help pass away the hours of work.

This record has two aims. First, to jolt the memory of North-east miners; to bring back to their minds songs which have as much feeling, be it tender or humorous or down-right aggressive, as anything the "pop" market can produce, and which are far more akin to the reality of their lives. The second aim is to let people outside the North-east hear what miners think of themselves and their work. The accent might puzzle and be hard to break down, but with a little patience and a lot of listening, a wealth of humour and an understanding of the miners' personality will be there for the taking.

LOUIS KILLEN

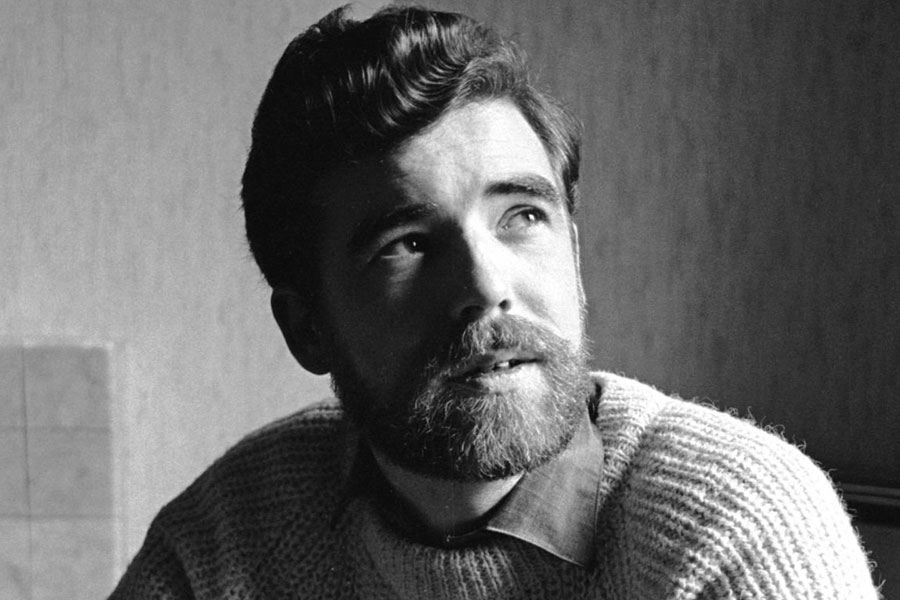

LOUIS KILLEN, born in Gateshead-on-Tyne, Co. Durham, comes from a singing family. Local songs made up a large part of the family repertoire. He has become well known, throughput the country, as a folksinger, and is one of the few singers in the folk revival to use a traditional instrument, the concertina, with which to accompany himself. A cabinet-maker by trade, he has worked at various jobs and now makes singing and the study of folk-music his full time profession.

JOHNNY HANDLE is the pseudonym for a young man who is making a prominent name for himself as a writer of "Geordie" mining songs. He has worked in the pits for eleven years and is a surveyor. His interest in folk-music stems from jazz: he has led several bands. In 1958 he helped Louis Killen form Newcastle-upon-Tyne's first folk club, "Folksong and Ballad". Born in Newcastle, he finds mining songs of the past an inspiration for the songs he himself writes. He, like Killen, often uses a traditional instrument, the melodeon, to accompany his singing.

COLIN ROSS, who accompanies, on Northumbrian pipes and fiddle, two of the songs on this record, is a sculptor and teacher from North Shields. He is well known on Tyneside as a folk musician and plays for morris, sword, and country dance teams. He joined Newcastle's "Folksong and Ballad" club in 1961 as resident musician.

BLACK-LEG MINERS

It's in the evenin' after dark,

When the black-leg miner creeps to work,

Wi' his moleskin pants and dorty shart,

There goes the black-leg miners.

They take their picks and down they go

To hew the coal that lies below;

But there's not a woman in this town row

Will look at a black-leg miner.

O, Deleval is a terrible place;

They rub wet clay in the black-legs face,

And around the heap they run a foot race

To catch the black-leg miner.

And divvent gan near the Seghill mine,

Across the Way they stretch a line

To catch the throat and break the spine

Of the dirty black-leg miners.

They'll take your tools and duds as well,

And hoy them doon the pit of hell;

Doon ye go and fare y' well,

Ye dorty black-leg miners.

So join the Union while ye may,

Don't wait til your dyin' day—

'Cause that may not be far away

Ye dorty black-les miners.

This Northumberland pit song was collected from Mr. W. Sampey, of Bishop Auckland, Co. Durham, in 1949.

The reprisals against black-legs were common occurrences during the strikes of the last century in the Northumbrian Coalfields when the owners brought Welsh, Irish and Cornish labour into the Field in attempts to break the Unions.

THE COLLIERS' RANT

As me and me marra was gannin to wark,

We met wi' the devil, it was in the dark;

I upwi' me pick, it bein in the neet,

And knocked off his horns, likewise his club feet.

Follow the horses, Johnny me laddie,

Follow them through, me canny lad, oh!

Follow the horses, Johnny me laddie,

Hey, lad, lie away, me canny lad, oh!

As me and me marra was puttin the tram,

The lowe it went oot and me marra went wrang;

Ye would have laughed had ye seen the gam,

And Nick got me marra, but I got the tram.

Oh, marra, oh, marra, what dost thou think?

I've broken me bottle and spilt a' me drink;

I've lost a' me shin-splints amang the greet stanes;

Draw me to the shaft, lad, it's time to gan hame.

Oh, marra, oh, marra, where hest thou been?

Drivin the drift frae the low seam,

Drivin the drift frae the low seam;

Haud up the lowe, lad, de'il stop oot they een!

Oh, marra, oh, marra, this wor pay week.

We'll get penny loaves and drink to wor beek;

And we'll fill up wor bumper and roond it shall go.

Follow the horses, me Johnny lad, oh!

There is me horse, and there is me tram,

Twe horns full of grease will myek her to gan;

There is me hoggers, likewise me half shoon,

And smash me heart, marra, me puttin's a' done!

THE COLLIERS' RANT is perhaps one of the oldest of mining songs in this country. It was currently popular (and for how long we don't know} when Ritson published it in his NORTHUMBFRLAND GARLAND, 1793. And it is still a popular piece among colliery choirs in the North-east.

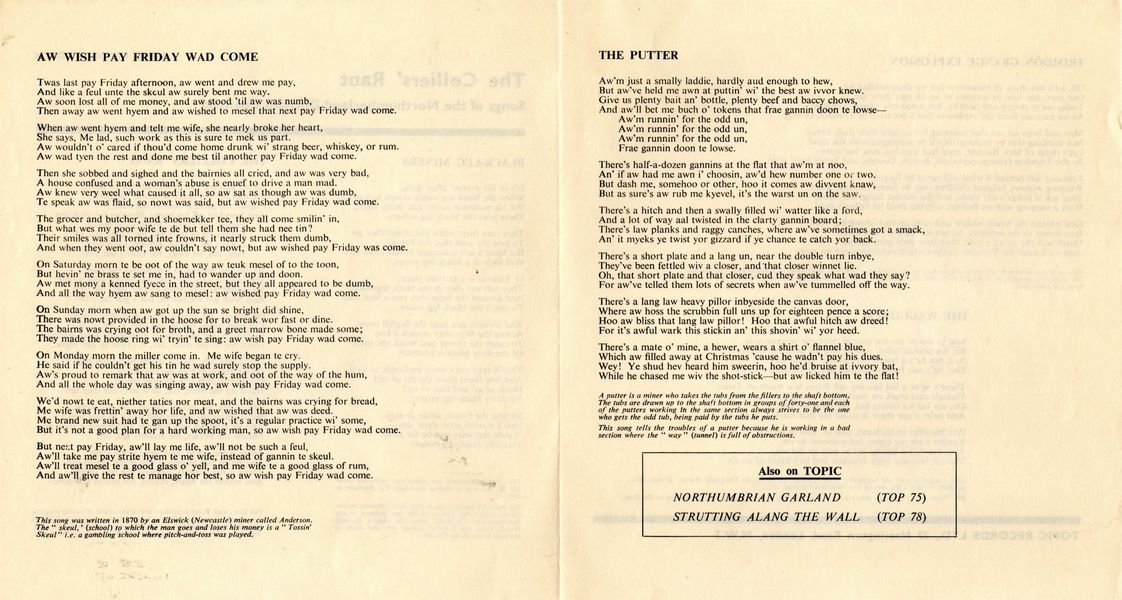

AW WISH PAY FRIDAY WAD COME

Twas last pay Friday afternoon, aw went and drew me pay,

And like a feul unte the skcul aw surely bent me way.

Aw soon lost all of me money, and aw stood 'til aw was numb,

Then away aw went hyem and aw wished to mesel that next pay Friday wad come.

When aw went hyem and telt me wife, she nearly broke her heart,

She says, Me lad, such work as this sure te mek us part.

Aw wouldn't o' cared if thou'd come home drunk wi' strang beer, whiskey, or rum.

Aw wad tyen the rest and done me best til another pay Friday wad come.

Then she sobbed and sighed and the bairnies all cried, and aw was very bad,

A house confused and a woman's abuse is enuef to drive a man mad.

Aw knew very weel what caused it all, so aw sat as though aw was dumb,

Te speak aw was flaid, so nowt was said, but aw wished pay Friday wad come.

The grocer and butcher, and shoemekker tee, they all come smilin' in,

But what wes my poor wife te de but tell them she had nee tin?

Their smiles was all torned inte frowns, it nearly struck them dumb,

And when they went oot, aw couldn't say nowt, but aw wished pay Friday was come.

On Saturday morn te be oot of the way aw teuk mesel of to the toon,

But hevin' ne brass te set me in, had to wander up and doon.

Aw met mony a kenned fyece in the street, but they all appeared to be dumb,

And all the way hyem aw sang to mesel: aw wished pay Friday wad come.

On Sunday morn when aw got up the sun se bright did shine,

There was nowt provided in the hoose for to break wor fast or dine.

The bairns was crying oot for broth, and a greet marrow bone made some;

They made the hoose ring wi' tryin' te sing: aw wish pay Friday wad come.

On Monday morn the miller come in. Me wife began te cry.

He said if he couldn't get his tin he wad surely stop the supply.

Aw's proud to remark that aw was at work, and oot of the way of the hum,

And all the whole day was singing away, aw wish pay Friday wad come.

We'd nowt te eat, niether taties nor meat, and the bairns was crying for bread,

Me wife was frettin' away hor life, and aw wished that aw was deed.

Me brand new suit had te gan up the spoot, it's a regular practice wi' some,

But it's not a good plan for a hard working man, so aw wish pay Friday wad come.

But next pay Friday, aw'll lay me life, aw'll not be such a feul,

Aw'll take me pay strite hyem te me wife, instead of gannin te skeul.

Aw'll treat mesel te a good glass o' yell, and me wife te a good glass of rum,

And aw'll give the rest te manage hor best, so aw wish pay Friday wad come.

This song was written in 1870 by an Elswick (Newcastle} miner called Anderson. The "skeull" (school) to which the man goes and loses his money is a "Tossin' Skeul" i.e. a gambling school where pitch-and-toss was played.

THE PUTTER

Aw'm just a smally laddie, hardly aud enough to hew,

But aw've held me awn at puttin' wi' the best aw ivvor knew.

Give us plenty bait an' bottle, plenty beef and baccy chows,

And aw'll bet me buch o' tokens that frae gannin doon te lowse—

Aw'm runnin' for the odd un,

Aw'm runnin' for the odd un,

Aw'm runnin' for the odd un,

Frae gannin doon te lowse.

There's half-a-dozen gannins at the flat that aw'm at noo,

An' if aw had me awn i' choosin, aw'd hew number one or two.

But dash me, somehoo or other, hoo it comes aw divvent knaw,

But as sure's aw rub me kyevel, it's the warst un on the saw.

There's a hitch and then a swally filled wi' watter like a ford,

And a lot of way aal twisted in the clarty gannin board;

There's law planks and raggy canches, where aw've sometimes got a smack,

An' it myeks ye twist yor gizzard if ye chance te catch yor back.

There's a short plate and a lang un, near the double turn inbye,

They've been fettled wiv a closer, and that closer winnet lie.

Oh, that short plate and that closer, cud they speak what wad they say?

For aw've telled them lots of secrets when aw've tummelled off the way.

There's a lang law heavy pillor inbyeside the canvas door,

Where aw hoss the scrubbin full uns up for eighteen pence a score;

Hoo aw bliss that lang law pillor! Hoo that awful hitch aw dreed!

For it's awful wark this stickin an' this shovin' wi' yor heed.

There's a mate o' mine, a hewer, wears a shirt o' flannel blue,

Which aw filled away at Christmas 'cause he wadn't pay his dues.

Wey! Ye shud hev heard him sweerin, hoo he'd bruise at ivvory bat,

While he chased me wiv the shot-stick-but aw licked him te the flat!

A putter is a miner who takes the tubs from the fillers to the shaft bottom. The tubs are drawn up to the shaft bottom in groups of forty-one and each of the putters working th the same section always strives to be the one who gets the odd tub, being paid by the tubs he puts.

This song tells the troubles of a putter because he is working in a bad section where the "way" (tunnel) is full of obstructions.

TRIMDON GRANGE EXPLOSION

Oh, let's not think of tomorrow lest we disappointed be.

Our joys may turn to sorrows as we all may daily see.

Today we're strong and healthy, but tomorrow comes a change,

As we may see from the explosion that's occurred at Trimdon Grange.

Men and boys set out that morning for to earn their daily bread,

Not thinking that by evening they'd be numbered with the dead.

Let's think of Mrs. Burnett, once had sons but now has none—

By the Trimdon Grange explosion, Joseph, George, and James have gone.

February left behind it what will never be forgot;

Weeping widows, helpless children may be found in many a cot.

They ask if father's left them, and the mother hangs her head,

With a weeping widows feelings tells the child its father's dead.

God protect the lonely widow and raise up each drooping head;

Be a father to the orphans, do not let them cry for bread.

Death will pay us all a visit, they have only gone before,

And we'll meet the Trimdon victims where explosions are no more.

This song was written by the great mining bard of the North-east, Thomas Armstrong, of Tanfield Lea, Co. Durham. he explosion occurred on February 16th, 1882 at the Trimdon Grange Colliery, Co. Durham. Seventy-four men and boys lost their lives.

THE WAGGONER

Saw ye oot o' my lad gannin doon the waggon-way,

Wi' his pocket full o' money and his poke full o' hay?

Aye, but he's a bonny lad, as ever ye did see,

Tho' he's sair frowsy-freckled and he's blind of an e'e.

There's ne'er a lad like my lad drives te a staith on Tyne:,

Though coal black on work-days, on holidays he's fine.

Oh, my lad's a bonny lad, the bonniest I see,

And ne'er a ane there is could say that black is iv his e'e.

Wiv his siller in his hand, and wi' love in his e'e,

Yonder I see me canny lad a-comin' to me.

Aye, but he's a bonny lad as ever ye did see,

Though he's sair pock-brocken and he's blind of an e'e.

This another very old North-east song—perhaps as old as the COLLIERS' RANT. It was first published in Dell's RHYMES OF THE NORTHERN BARDS, 1812.

The "hero" is a waggoner who takes the coal from the pit heads to the coaling staithes on the Tyne.