|

|

Sleeve Notes

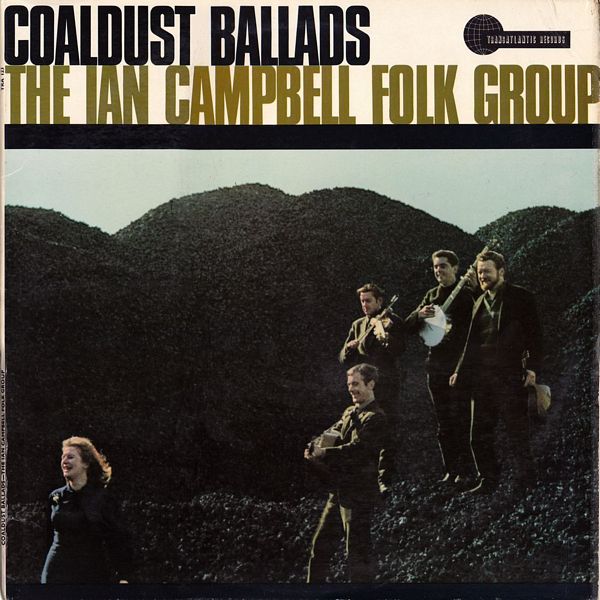

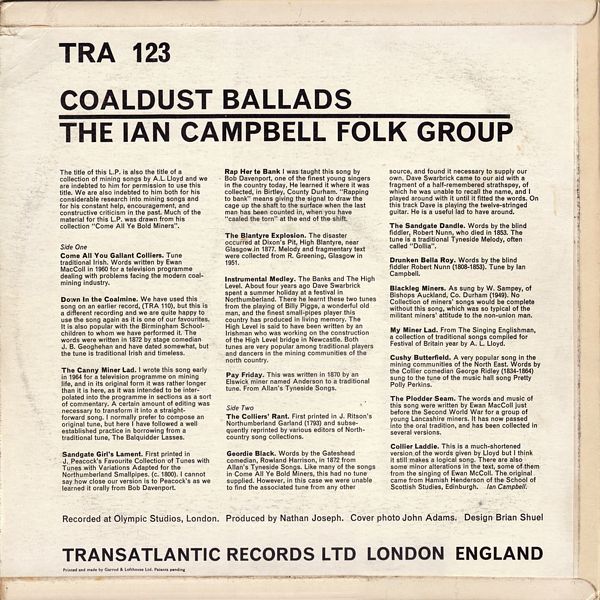

The title of this L.P. is also the title of a collection of mining songs by A. L. Lloyd and we are indebted to him for permission to use this title. We are also indebted to him both for his considerable research into mining songs and for his constant help, encouragement, and constructive criticism in the past. Much of the material for this L.P. was drawn from his collection "Come All Ye Bold Miners".

Come All You Gallant Colliers. Tune traditional Irish. Words written by Ewan MacColl in 1960 for a television programme dealing with problems facing the modern coalmining industry.

Down In the Coalmine. We have used this song on an earlier record, (TRA 110), but this a different recording and we are quite happy to use the song again as it is one of our favourites. It is also popular with the Birmingham School-children to whom we have performed it. The words were written in 1872 by stage comedian J. B. Geoghehan and have dated somewhat, but the tune is traditional Irish and timeless.

The Canny Miner Lad. I wrote this song early in 1964 for a television programme on mining life, and in its original form it was rather longer than it is here, as it was intended to be interpolated into the programme in sections as a sort of commentary. A certain amount of editing was necessary to transform it into a straightforward song. I normally prefer to compose an original tune, but here I have followed a well-established practice in borrowing from a traditional tune, The Balquidder Lasses.

Sandgate Girl's Lament. First printed in J. Peacock's Favourite Collection of Tunes with Tunes with Variations Adapted for the Northumberland Small pipes. (c. 1800). I cannot say how close our version is to Peacock's as we learned it orally from Bob Davenport.

Rap Her to Bank. I was taught this song by Bob Davenport, one of the finest young singers in the country today, He learned it where it was collected, in Birtley, County Durham. "Rapping to bank" means giving the signal to draw the cage up the shaft to the surface when the last man has been counted in, when you have "caaled the torn" at the end of the shift.

The Blantyre Explosion. The disaster occurred at Dixon's Pit, High Blantyre, near Glasgow in 1877. Melody and fragmentary text were collected from R. Greening, Glasgow in 1951.

Instrumental Medley. The Banks and the High Level. About four years ago, Dave Swarbrick spent a summer holiday at a festival in Northumberland. There he learnt these two tunes from the playing of Billy Pigge, a wonderful old man, and the finest small-pipes player this country has produced in living memory. The High Level is said to have been written by an Irishman who was working on the construction of the High Level Bridge in Newcastle. Both tunes are very popular among traditional players and dancers in the mining communities of the North Country.

Pay Friday. This was written in 1870 by an Elswick miner named Anderson to a traditional tune. From Allans Tyneside Songs.

The Colliers' Rant. First printed in J. Ritson's Northumberland Garland (1793) and subsequently reprinted by various editors of North-country song collections.

Geordie Black. Words by the Gateshead comedian, Rowland Harrison, in 1872 from Allans Tyneside Songs. Like many of the songs in Come All Ye Bold Miners, this had no tune supplied. However, in this case we were unable to find the associated tune from any other source, and found it necessary to supply our own. Dave Swarbrick came to our aid with a fragment of a half-remembered strathspey, of which he was unable to recall the name, and I played around with it until it fitted the words. On this track, Dave is playing the twelve-stringed guitar. He is a useful lad to have around.

The Sandgate Dandle. Words by the blind fiddler, Robert Nunn, who died in 1853. The tune is a traditional Tyneside Melody, often called "Dollia".

Drunken Bella Roy. Words by the blind fiddler Robert Nunn (1808-1853). Tune by Ian Campbell.

Blackleg Miners. As sung by W. Sampey, of Bishops Auckland, Co. Durham (1949). No Collection of miners' songs would be complete without this song, which was so typical of the militant miners' attitude to the non-union man.

My Miner Lad. From The Singing Englishman, a collection of traditional songs compiled for Festival of Britain year by A. L. Lloyd.

Cushy Butterfield. A very popular song in the mining communities of the North East. Words by the Collier comedian George Ridley (1834-1864) sung to the tune of the music hall song Pretty Polly Perkins.

The Plodder Seam. The words and music of this song were written by Ewan MacColl just before the Second World War for a group of young Lancashire miners. It has now passed into the oral tradition, and has been collected in several versions.

Collier Laddie. This a much-shortened version of the words given by Lloyd but I think it still makes a logical song. There are also some minor alterations in the text, some of them from the singing of Ewan McColl. The original came from Hamish Henderson of the School of Scottish Studies, Edinburgh.

Ian Campbell