|

|

| more images |

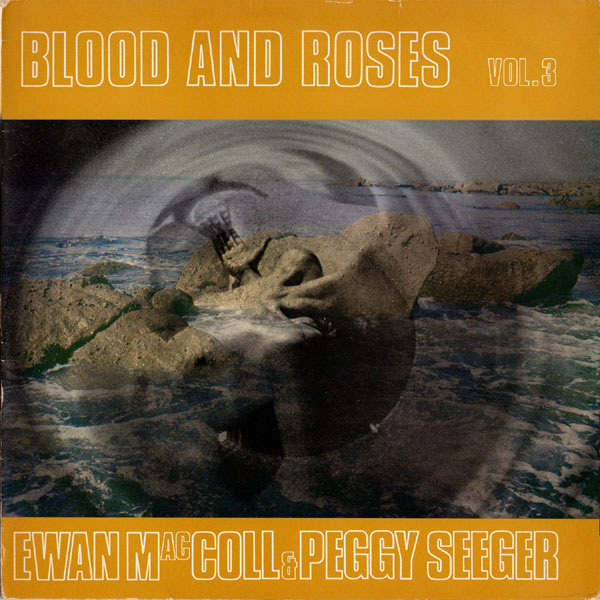

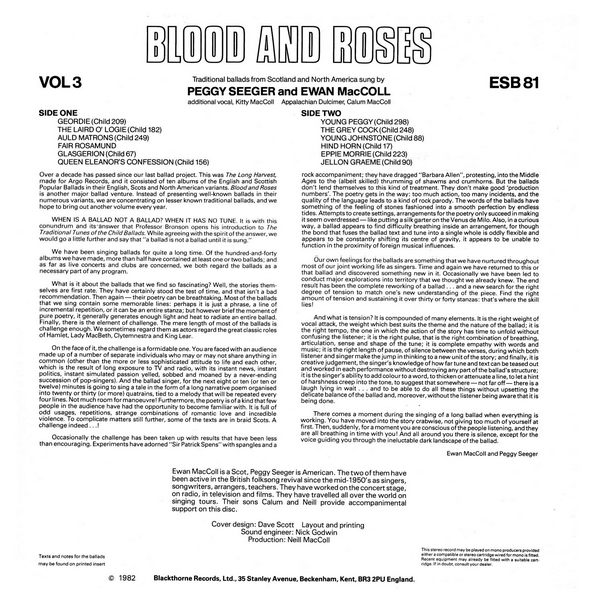

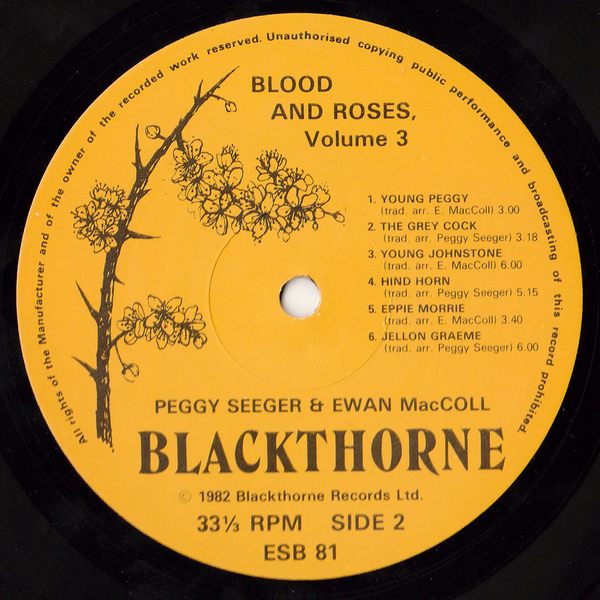

Sleeve Notes

Traditional ballads from Scotland and North America sung by PEGGY SEEGER and EWAN MacCOLL

Over a decade has passed since our last ballad project. This was The Long Harvest, made for Argo Records, and it consisted of ten albums of the English and Scottish Popular Ballads in their English, Scots and North American variants. Blood and Roses is another major ballad venture. Instead of presenting well-known ballads in their numerous variants, we are concentrating on lesser known traditional ballads, and we hope to bring out another volume every year.

WHEN IS A BALLAD NOT A BALLAD? WHEN IT HAS NO TUNE. It is with this conundrum and its answer that Professor Bronson opens his introduction to The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads. While agreeing with the spirit of the answer, we would go a little further and say that "a ballad is not a ballad until it is sung."

We have been singing ballads for quite a long time. Of the hundred-and-forty albums we have made, more than half have contained at least one or two ballads; and as far as live concerts and clubs are concerned, we both regard the ballads as a necessary part of any program.

What is it about the ballads that we find so fascinating? Well, the stories them-selves are first rate. They have certainly stood the test of time, and that isn't a bad recommendation. Then again — their poetry can be breathtaking. Most of the ballads that we sing contain some memorable lines: perhaps it is just a phrase, a line of incremental repetition, or it can be an entire stanza; but however brief the moment of pure poetry, it generally generates enough light and heat to radiate an entire ballad. Finally, there is the element of challenge. The mere length of most of the ballads is challenge enough. We sometimes regard them as actors regard the great classic roles of Hamlet, Lady MacBeth, Clytemnestra and King Lear.

On the face of it, the challenge is a formidable one. You are faced with an audience made up of a number of separate individuals who may or may not share anything in common (other than the more or less sophisticated attitude to life and each other, which is the result of long exposure to TV and radio, with its instant news, instant politics, instant simulated passion yelled, sobbed and moaned by a never-ending succession of pop-singers). And the ballad singer, for the next eight or ten (or ten or twelve) minutes is going to sing a tale in the form of a long narrative poem organised into twenty or thirty (or more) quatrains, tied to a melody that will be repeated every four lines. Not much room for manoeuvre! Furthermore, the poetry is of a kind that few people in the audience have had the opportunity to become familiar with. It is full of odd usages, repetitions, strange combinations of romantic love and incredible violence. To complicate matters still further, some of the texts are in braid Scots. A challenge indeed …!

Occasionally the challenge has been taken up with results that have been less than encouraging. Experiments have adorned "Sir Patrick Spens" with spangles and a rock accompaniment; they have dragged "Barbara Allen", protesting, into the Middle Ages to the (albeit skilled) thrumming of shawms and crumhorns. But the ballads don't lend themselves to this kind of treatment. They don't make good 'production numbers'. The poetry gets in the way: too much action, too many incidents, and the quality of the language leads to a kind of rock parody. The words of the ballads have something of the feeling of stones fashioned into a smooth perfection by endless tides. Attempts to create settings, arrangements for the poetry only succeed in making it seem overdressed — like putting a silk garter on the Venus de Milo. Also, in a curious way, a ballad appears to find difficulty breathing inside an arrangement, for though the bond that fuses the ballad text and tune into a single whole is oddly flexible and appears to be constantly shifting its centre of gravity, it appears to be unable to function in the proximity of foreign musical influences.

Our own feelings for the ballads are something that we have nurtured throughout most of our joint working life as singers. Time and again we have returned to this or that ballad and discovered something new in it. Occasionally we have been led to conduct major explorations into territory that we thought we already knew. The end result has been the complete reworking of a ballad … and a new search for the right degree of tension to match one's new understanding of the piece. Find the right amount of tension and sustaining it over thirty or forty stanzas: that's where the skill lies!

And what is tension? It is compounded of many elements. It is the right weight of vocal attack, the weight which best suits the theme and the nature of the ballad; it is the right tempo, the one in which the action of the story has time to unfold without confusing the listener; it is the right pulse, that is the right combination of breathing, articulation, sense and shape of the tune; it is complete empathy with words and music; it is the right length of pause, of silence between the verses, during which both listener and singer make the jump in thinking to a new unit of the story; and finally, it is creative judgment, the singer's knowledge of how far tune and text can be teased out and worked in each performance without destroying any part of the ballad's structure; it is the singer's ability to add colour to a word, to thicken or attenuate a line, to let a hint of harshness creep into the tone, to suggest that somewhere — not far off— there is a laugh lying in wait … and to be able to do all these things without upsetting the delicate balance of the ballad and, moreover, without the listener being aware that it is being done.

There comes a moment during the singing of a long ballad when everything is working. You have moved into the story crabwise, not giving too much of yourself at first. Then, suddenly, for a moment you are conscious of the people listening, and they are all breathing in time with you! And all around you there is silence, except for the voice guiding you through the ineluctable dark landscape of the ballad.

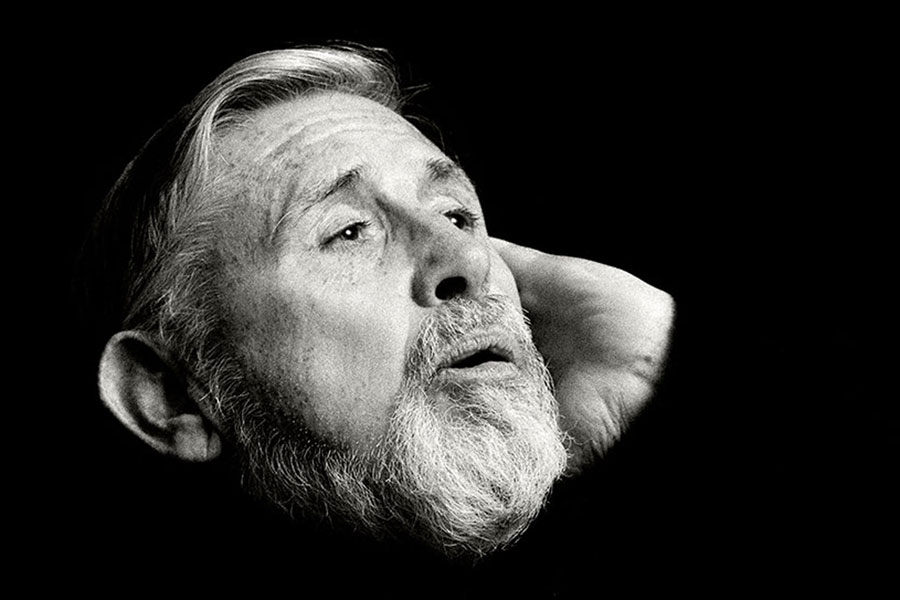

Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger

Ewan MacColl is a Scot, Peggy Seeger is American. The two of them have been active in the British folksong revial since the mid-1950's as singers, songwriters, arrangers, teachers. They have worked on the concert stage, on radio, in television and films. They have travelled all over the world on singing tours. Their sons Calum and Neill provide accompanimental support on this disc.