|

|

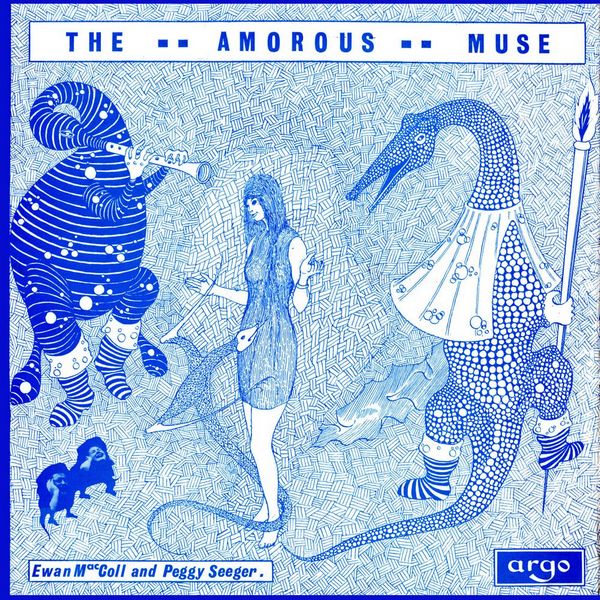

Sleeve Notes

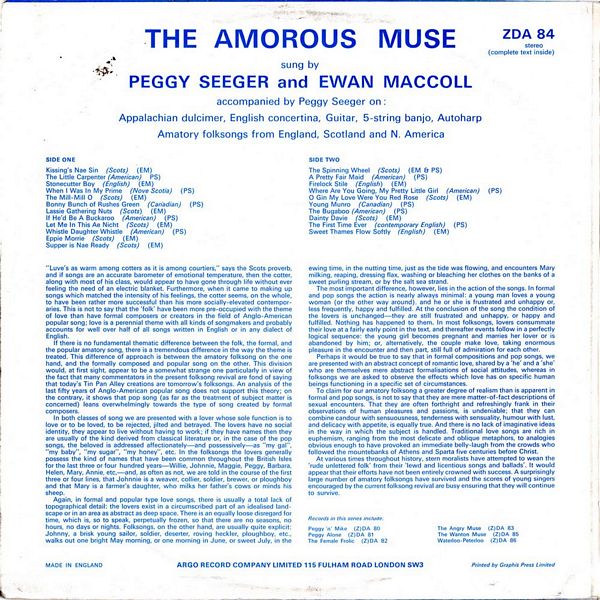

"Luve's as warm among cotters as it is among courtiers," says the Scots proverb, and if songs are an accurate barometer of emotional temperature, then the cotter, along with most of his class, would appear to have gone through life without ever feeling the need of an electric blanket.

Furthermore, when it came to making up songs which matched the intensity of his feelings, the cotter seems, on the whole, to have been rather more successful than his more socially-elevated contemporaries. This is not to say that the ‘folk' have been more pre-occupied with the theme of love than have formal composers or creators in the field of Anglo-American popular song; love is a perennial theme with all kinds of songmakers and probably accounts for well over half of all songs written in English or in any dialect of English.

Tin Pan Alley

If there is no fundamental thematic difference between the folk, the formal, and the popular amatory song, there is a tremendous difference in the way the theme is treated. This difference of approach is between the amatory folksong on the one hand, and the formally composed and popular song on the other.

This division would, at first sight, appear to be a somewhat strange one particularly in view of the fact that many commentators in the present folksong revival are fond of saying that today's Tin Pan Alley creations are tomorrow's folksongs. An analysis of the last fifty years of Anglo-American popular song does not support this theory; on the contrary, it shows that pop song (as far as the treatment of subject matter is concerned) leans overwhelmingly towards the type of song created by formal composers.

Maggie vs ‘my honey'

In both classes of song we are presented with a lover whose sole function is to love or to be loved, to be rejected, jilted and betrayed. The lovers have no social identity, they appear to live without having to work; if they have names then they are usually of the kind derived from classical literature or, in the case of the pop songs, the beloved is addressed affectionately — and possessively — as "my gal", "my baby", "my sugar", "my honey", etc.

In the folksongs the lovers generally possess the kind of names that have been common throughout the British Isles for the last three or four hundred years —Willie, Johnnie, Maggie, Peggy, Barbara, Helen, Mary, Annie, etc, —and, as often as not, we are told in the course of the first three or four lines, that Johnnie is a weaver, collier, soldier, brewer, or ploughboy and that Mary is a farmer's daughter, who milks her father's cows or minds his sheep.

Place

Again, in formal and popular type love songs, there is usually a total lack of topographical detail: the lovers exist in a circumscribed part of an idealised landscape or in an area as abstract as deep space. There is an equally loose disregard for time, which is, so to speak, perpetually frozen, so that there are no seasons, no hours, no days or nights.

Folksongs, on the other hand, are usually quite explicit; Johnny, a brisk young sailor, soldier, deserter, roving heckler, ploughboy, etc., walks out one bright May morning, or one morning in June, or sweet July, in the ewing time, in the nutting time, just as the tide was flowing, and encounters Mary milking, reaping, dressing flax, washing or bleaching her clothes on the banks of a sweet purling stream, or by the salt sea strand.

Action

The most important difference, however, lies in the action of the songs, In formal and pop songs the action is nearly always minimal; a young man loves a young woman (or the other way around), and he or she is frustrated and unhappy or, less frequently, happy and fulfilled.

At the conclusion of the song the condition of the lovers is unchanged —they are still frustrated and unhappy, or happy and fulfilled. Nothing has happened to them. In most folksongs, lovers consummate their love at a fairly early point in the text, and thereafter events follow in a perfectly logical sequence; the young girl becomes pregnant and marries her lover or is abandoned by him; or, alternatively, the couple make love, taking enormous pleasure in the encounter and then part, still full of admiration for each other.

Abstract pop, specific folk

Perhaps it would be true to say that in formal compositions and pop songs, we are presented with an abstract concept of romantic love, shared by a ‘he' and a ‘she' who are themselves mere abstract formalisations of social attitudes, whereas in folksongs we are asked to observe the effects which love has on specific human beings functioning in a specific set of circumstances.

To claim for our amatory folksong a greater degree of realism than is apparent in formal and pop songs, is not to say that they are mere matter-of-fact descriptions of sexual encounters, That they are often forthright and refreshingly frank in their observations of human pleasures and passions, is undeniable; that they can combine candour with sensuousness, tenderness with sensuality, humour with lust, and delicacy with appetite, is equally true.

And there is no lack of imaginative ideas in the way in which the subject is handled. Traditional love songs are rich in euphemism, ranging from the most delicate and oblique metaphors, to analogies obvious enough to have provoked an immediate belly-laugh from the crowds who followed the mountebanks of Athens and Sparta five centuries before Christ.

At various times throughout history, stern moralists have attempted to wean the ‘rude unlettered folk' from their ‘lewd and licentious songs and ballads'. It would appear that their efforts have not been entirely crowned with success. A surprisingly large number of amatory folksongs have survived and the scores of young singers encouraged by the current folksong revival are busy ensuring that they will continue to survive.