|

|

|

|

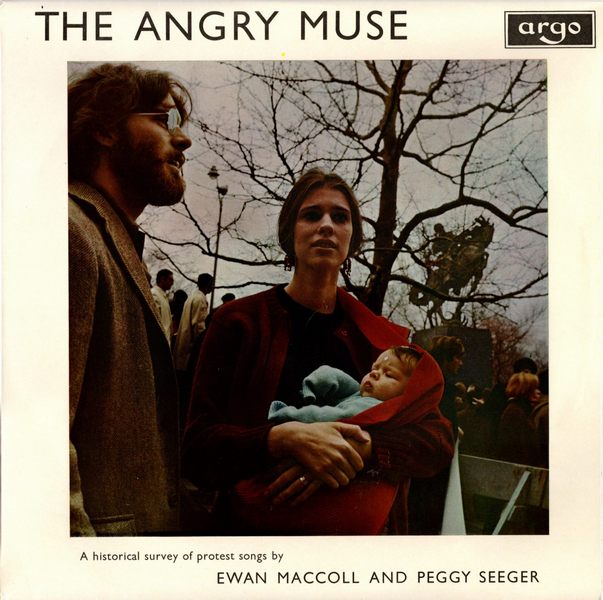

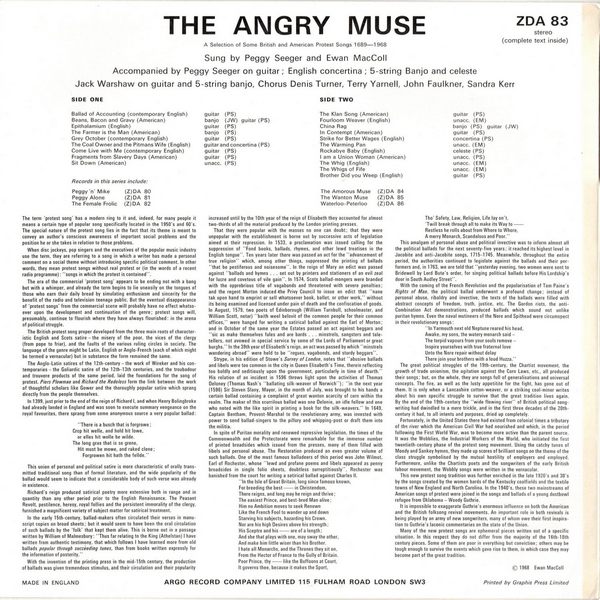

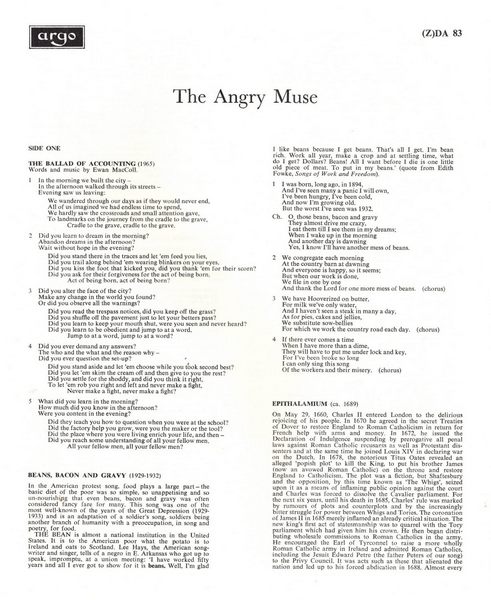

Sleeve Notes

The term 'protest song' has a modern ring to it and, indeed, for many people it means a certain type of popular song specifically located in the 1950's and 60's. The special nature of the protest song lies in the fact that its theme is meant to convey an author's conscious awareness of important social problems and the position he or she takes in relation to those problems.

When disc jockeys, pop singers and the executives of the popular music industry use the term, they are referring to a song in which a writer has made a personal comment on a social theme without introducing specific political comment. In other words, they mean protest songs without real protest or (in the words of a recent radio programme): "songs in which the protest is contained".

The era of the commercial 'protest song' appears to be ending not with a bang but with a whimper, and already the term begins to lie uneasily on the tongues of those who earn their daily bread by simulating enthusiasm and sincerity for the benefit of the radio and television teenage public. But the eventual disappearance of 'protest songs' from the commercial scene will probably have no effect whatsoever upon the development and continuation of the genre; protest songs will, presumably, continue to flourish where they have always flourished: in the arena of political struggle.

The British protest song proper developed from the three main roots of characteristic English and Scots satire — the misery of the poor, the vices of the clergy (from pope to friar), and the faults of the various ruling circles in society. The language of the genre might be Latin, English or Anglo-French (each of which might be termed a vernacular) but in substance the form remained the same.

The Anglo-Latin satires of the 12th-century — the work of Wireker and his contemporaries — the Goliardic satire of the 12th-l3th centuries, and the troubadour and trouvere products of the same period, laid the foundations for the song of protest. Piers Plowman and Richard the Redeless form the link between the work of thoughtful scholars like Gower and the thoroughly popular satire which sprang directly from the people themselves.

In 1399, just prior to the end of the reign of Richard I, and when Henry BolinUKoke had already landed in England and was soon to execute summary vengeance on the royal favourites, there sprang from some anonymous source a very popular ballad:

"There is a busch that is forgrowe;

Crop hit welle, and hold hit lowe,

or elles hit wolle be wilde.

The long gras that is so grene,

Hit must be mowe. and raked clene;

Forgrowen hit hath the fellde."

This union of personal and political satire is more characteristic of orally transmitted traditional song than of formal literature, and the wide popularity of the ballad would seem to indicate that a considerable body of such verse was already in existence.

Richard's reign produced satirical poetry more extensive both in range and in quantity than any other period prior to the English Renaissance. The Peasant Revolt, pestilence, heresy, royal follies and the persistent immorality of the clergy, furnished a magnificent variety of subject matter for satirical treatment.

In the early 15th-century, ballad-makers often circulated their verses in manuscript copies on broad sheets; but it would seem to have been the oral circulation of such ballads by the 'folk' that kept them alive. This is borne out in a passage written by William of Malmesbury: "Thus far relating to the King (Athelstan) I have written from authentic testimony, that which follows I have learned more from old ballads popular through succeeding tunes, than from books written expressly for the information of posterity."

With the invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century, the production of ballads was given tremendous stimulus, and their circulation and their popularity increased until by the 10th year of the reign of Elisabeth they accounted for almost two-thirds of all the material produced by the London printing presses.

That they were popular with the masses no one can doubt; that they were unpopular with the establishment is borne out by successive acts of legislation aimed at their repression. In 1533, a proclamation was issued calling for the suppression of "Fond books, ballads, rhymes, and other lewd treatises in the English tongue". Ten years later there was passed an act for the "advancement of true religion" which, among other things, suppressed the printing of ballads "that be pestiferous and noisesome". In the reign of Mary an edict was passed against "ballads and hymns ... set out by printers and stationers of an evil zeal for lucre and covetous of vile gain". In 1574, Scots ballad-mongers were branded with the opprobrious title of vagabonds and threatened with severe penalties; and the regent Morton induced the Privy Council to issue an edict that "nane tak upon hand to emprint or sell whatsoever book, ballet, or other werk," without its being examined and licensed under pain of death and the confiscation of goods. In August, 1579, two poets of Edinborough (William Turnbull, schoolmaster, and William Scott, notar) "baith weel belovit of the common people for their common offices," were hanged for writing a satirical ballad against the Earl of Morton; and in October of the same year the Estates passed an act against beggars and "sic as make themselves fules and are bards … minstrels, sangsters and taletellers, not avowed in special service by some of the Lords of Parliament or great burghs." In the 39th year of Elisabeth's reign, an act was passed by which "minstrels wandering abroad" were held to be "rogues, vagabonds, and sturdy beggars".

Strype, in his edition of Stowe's Survey of London, notes that "abusive ballads and libels were too common in the city in Queen Elisabeth's Time, therein reflecting too boldly and seditiously upon the government, particularly in time of dearth." His relation of an incident in 1596 throws light upon the activities of Thomas Deloney (Thomas Nash's "ballating silk-weaver of Norwich"); "in the next year (1596) Sir Steven Slany, Mayor, in the month of July, was brought to his hands a certain ballad containing a complaint of great wanton scarcity of corn within the realm. The maker of this scurrilous ballad was one Delonie. an idle fellow and one who noted with the like spirit in printing a book for the silk-weavers." In 1649, Captain Bentham, Provost-Marshal to the revolutionary army, was invested with power to send ballad-singers to the pillory and whipping-post or draft them into the militia.

In spite of Puritan morality and renewed repressive legislation, the times of the Commonwealth and the Protectorate were remarkable for the immense number of printed broadsides which issued from the presses, many of them filled with libels and personal abuse. The Restoration produced an even greater volume of such ballads. One of the most famous balladeers of this period was John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester, whose "lewd and profane poems and libels appeared as penny broadsides in single folio sheets, doubtless surreptitiously". Rochester was banished from the court for writing a satirical ballad against Charles II.

"In the Isle of Great Britain, long since famous known,

For breeding the best — in Christendom,

There reigns, and long may he reign and thrive;

The easiest Prince, and best-bred Man alive;

Him no Ambition moves to seek Renown

Like the French Fool to wander up and down

Starving his subjects, hazarding his Crown.

Nor are his high Desires above his strength;

His Sceptre and his — are of a length;

And she that plays with one, may sway the other.

And make him little wiser than his Brother.

I hate all Monarchs, and the Thrones they sit on.

From the Hector of France to the Gully of Britain.

Poor Prince, thy — like the Buffoons at Court,

It governs thee, because it makes the Sport,

Tho' Safety, Law, Religion, Life lay on't,

'Twill break through all to make its Way to —

Restless he rolls about from Whore to Whore,

A merry Monarch. Scandalous and Poor."

This amalgam of personal abuse and political invective was to inform almost all the political ballads for the next seventy-five years; it reached its highest level in Jacobite and anti-Jacobite songs, 1715-1745. Meanwhile, throughout the entire period, the authorities continued to legislate against the ballads and their performers and, in 1763, we are told that "yesterday evening, two women were sent to Bridewell by Lord Bute's order, for singing political ballads before His Lordship's door in South Audley Street".

With the coming of the French Revolution and the popularisation of Tom Paine's Rights of Man, the political ballad underwent a profound change; instead of personal abuse, ribaldry and invective, the texts of the ballads were filled with abstract concepts of freedom, truth, justice, etc. The Gordon riots, the anti-Combination Act demonstrations, produced ballads which sound not unlike puritan hymns. Even the naval mutineers of the Nore and Spithead were circumspect in their revolutionary songs:

"In Yarmouth next old Neptune reared his head.

Awake, my sons, the watery monarch said —

The torpid vapours from your souls remove —

Inspire yourselves with true fraternal love

Unto the Nore repair without delay

There join your brothers with a loud Huzza."

The great political struggles of the 19th-century, the Chartist movement, the growth of trade unionism, the agitation against the Corn Laws, etc., all produced their songs; but, on the whole, they are songs full of generalisations and universal concepts. The fire, as well as the lusty appetitite for the fight, has gone out of them. It is only when a Lancashire cotton-weaver, or a striking coal-miner writes about his own specific struggle to survive that the great tradition lives again. By the end of the 19th-century the "wide flowing river" of British political songwriting had dwindled to a mere trickle, and in the first three decades of the 20th-century it had. to all intents and purposes, dried up completely.

Fortunately, in the United States there had existed from colonial times a tributary of the river which the American Civil War had nourished and which, in the period following the First World War, was to become more active than the parent source. It was the Wobblies, the Industrial Workers of the World, who initiated the first twentieth-century phase of the protest song movement. Using the catchy tunes of Moody and Sankey hymns, they made up scores of brilliant songs on the theme of the class struggle symbolised by the mutual hostility of employers and employed. Furthermore, unlike the Chartists poets and the songwriters of the early British labour movement, the Wobbly songs were written in the vernacular.

This new protest song tradition was further enriched in the late 1920's and 30's by the songs created by the women bards of the Kentucky coalfields and the textile towns of New England and North Carolina. In the 1940's, these two mainstreams of American songs of protest were joined in the songs and ballads of a young dustbowl refugee from Oklahoma — Woody Guthrie.

It is impossible to exaggerate Guthrie's enormous influence on both the American and the British folksong revival movements. An important role in both revivals is being played by an army of new songwriters, many of whom owe their first inspiration to Guthrie's laconic commentaries on the state of the Union.

Many of the new protest songs are ephemeral pieces written out of a specific situation. In this respect they do not differ from the majority of the 16th-18th century pieces. Some of them are poor in everything hut conviction; others may be tough enough to survive the events which gave rise to them, in which case they may become part of the great tradition.

© 1968 Ewan MacColl