|

|

Sleeve Notes

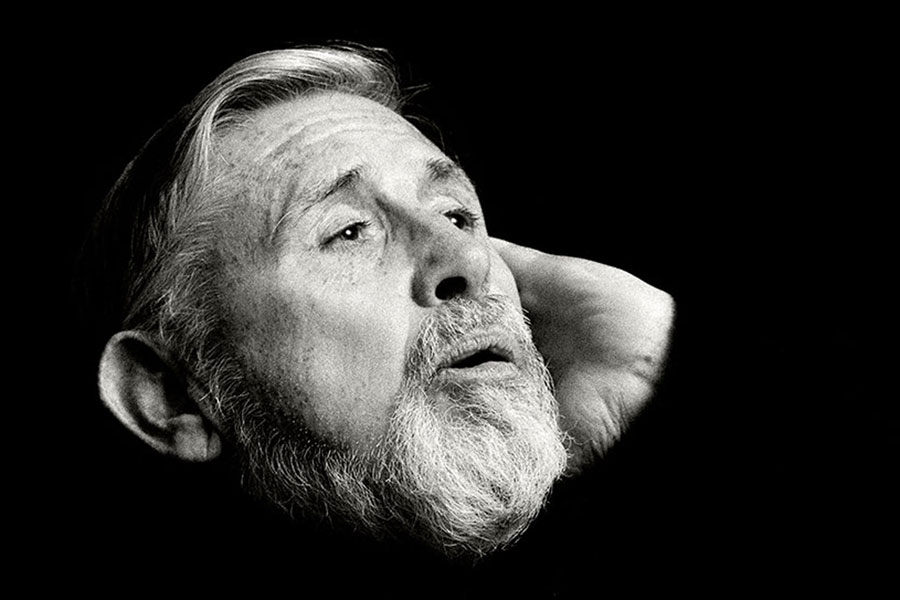

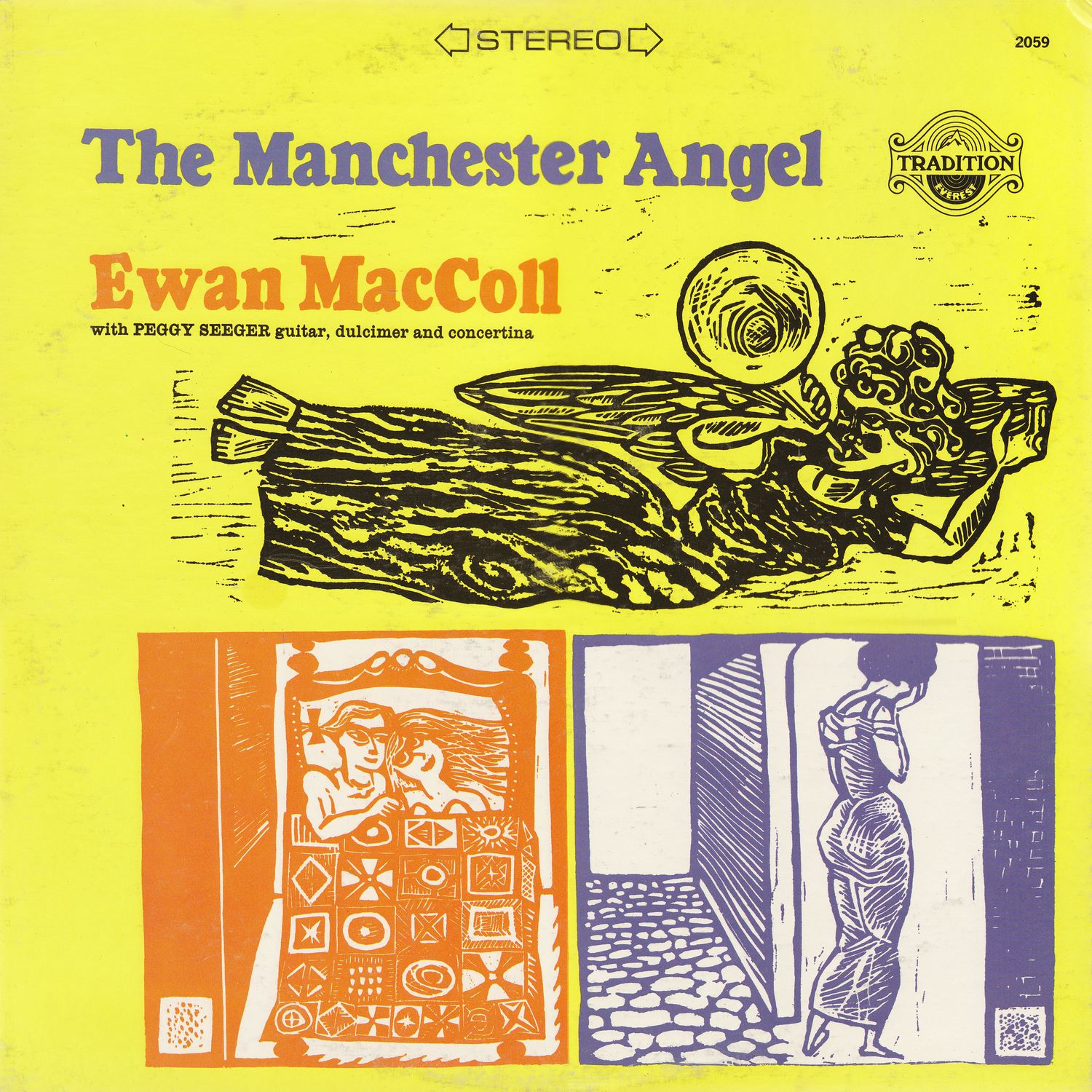

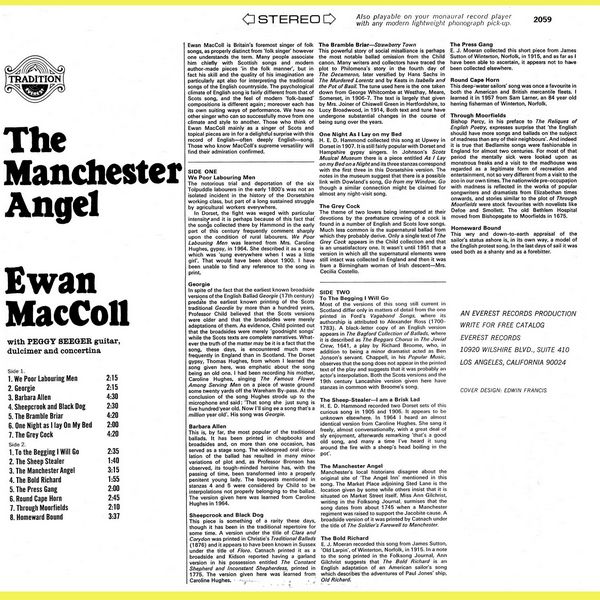

Ewan MacColl is Britain's foremost singer of folk songs, as properly distinct from 'folksinger' however one understands the term. Many people associate him chiefly with Scottish songs and modem author-made pieces 'in the folk manner', but in fact his skill and the quality of his imagination are particularly apt also for interpreting the traditional songs of the English countryside. The psychological climate of English song is fairly different from that of Scots song, and the feel of modern 'folk-based' compositions is different again; moreover each has its own suiting ways of performance. We have no other singer who can so successfully move from one climate and style to another. Those who think of Ewan MacColl mainly as a singer of Scots and topical pieces are in for a delightful surprise with this record of English — often deeply English — song. Those who know MacColl's supreme versatility will find their admiration confirmed.

We Poor Labouring Men — The notorious trial and deportation of the six Tolpuddle labourers in the early 1800's was not an isolated incident in the history of the Dorsetshire working class, but part of a long sustained struggle by agricultural workers everywhere.

In Dorset, the fight was waged with particular intensity and it is perhaps because of this fact that the songs collected there by Hammond in the early part of this century frequently comment sharply upon the condition of rural labourers. We Poor Labouring Men was learned from Mrs. Caroline Hughes, gypsy, in 1964. She described it as a song which was 'sung everywhere when I was a little girl'. That would have been about 1900. I have been unable to find any reference to the song in print.

Georgie — In spite of the fact that the earliest known broadside versions of the English Ballad Georgie (17th century) predate the earliest known printing of the Scots traditional Geordie by more than a hundred years, Professor Child believed that the Scots versions were older and that the broadsides were merely adaptations of them. As evidence, Child pointed out that the broadsides were merely 'goodnight songs' while the Scots texts are complete narratives. Whatever the truth of the matter may be it is a fact that the song, these days, is encountered much more frequently in England than in Scotland. The Dorset gypsy, Thomas Hughes, from whom I learned the song given here, was emphatic about the song being an old one. I had been recording his mother, Caroline Hughes, singing The Famous Flower Among Serving Men on a piece of waste ground some twenty yards off the Wareham By-pass. At the conclusion of the song Hughes strode up to the microphone and said: 'That song she just sung is five hundred year old. Now I'll sing ee a song that's a million year old'. His song was Georgie.

Barbara Allen — This is, by far, the most popular of the traditional ballads. It has been printed in chapbooks and broadsides and, on more than one occasion, has served as a stage song. The widespread oral circulation of the ballad has resulted in many minor variations of plot and, as Professor Bronson has observed, its tough-minded heroine has, with the passing of time, been transformed into a properly penitent young lady. The bequests mentioned in stanzas 4 and 5 were considered by Child to be interpolations not properly belonging to the ballad, The version given here was learned from Caroline Hughes in 1964.

Sheepcrook and Black Dog — This piece is something of a rarity these days, though it has been in the traditional repertoire for some time. A version under the title of Clara and Corydon was printed in Christie's Traditional Ballads (1876) and it appears to have been known in Sussex under the title of Floro. Catnach printed it as a broadside and Kidson reported having a garland version in his possession entitled The Constant Shepherd and Inconstant Shepherdess, printed in 1775. The version given here was learned from Caroline Hughes.

The Bramble Briar — Strawberry Town — This powerful story of social misalliance is perhaps the most notable ballad omission from the Child canon. Many writers and collectors have traced the plot to Philomena's story in the fourth day of The Decameron, later versified by Hans Sachs in The Murdered Lorentz and by Keats in Isabella and the Pot of Basil, The tune used here is the one taken down from George Whitcombe at Westhay, Meare, Somerset, in 1906-7. The text is largely that given by Mrs. Joiner of Chiswell Green in Hertfordshire, to Lucy Broadwood, in 1914, Both text and tune have undergone substantial changes in the course of being sung over the years.

One Night As I Lay on my Bed — H. E. D. Hammond collected this song at Upwey in Dorset in 1907. It is still fairly popular with Dorset and Hampshire gypsy singers. In Johnson's Scots Musical Museum there is a piece entitled As I Lay on my Bed on a Night and its three stanzas correspond with the first three in this Dorsetshire version. The notes in the museum suggest that there is a possible link with Dowland's song, Go from my Window, Go though a similar connection might be claimed for almost any night-visit song.

The Grey Cock — The theme of two lovers being interrupted at their devotions by the premature crowing of a cock is found in a number of English and Scots love songs. Much less common is the supernatural ballad from which they probably derive. Only a single text of The Grey Cock appears in the Child collection and that is an unsatisfactory one. It wasn't until 1951 that a version in which all the supernatural elements were still intact was collected in England and then it was from a Birmingham woman of Irish descent — Mrs. Cecilia Costello.

To The Begging I Will Go — Most of the versions of this song still current in Scotland differ only in matters of detail from the one printed in Ford's Vagabond Songs, where its authorship is attributed to Alexander Ross (1700-1783). A black-letter copy of an English version appears in The Bagford Collection of Ballads, where it is described as The Beggars Chorus in The Jovial Crew, 1641, a play by Richard Broome, who, in addition to being a minor dramatist acted as Ben Jonson's servant. Chappell, in his Popular Music, observes that the song does not appear in the printed text of the play and suggests that it was probably an actor's interpolation. Both the Scots versions and the 19th century Lancashire version given here have stanzas in common with Broome's song.

The Sheep-Stealer — I am a Brisk Lad — H. E. D. Hammond recorded two Dorset sets of this curious song in 1905 and 1906. It appears to be unknown elsewhere. In 1964 I heard an almost identical version from Caroline Hughes. She sang it freely, almost conversationally, with a great deal of sly enjoyment, afterwards remarking 'that's a good old song, and many a time I've heard it sung around the fire with a sheep's head boiling in the pot'.

The Manchester Angel — Manchester's local historians disagree about the original site of 'The Angel Inn' mentioned in this song. The Market Place adjoining Sted Lane is the location given by some while others insist that it is situated on Market Street itself. Miss Ann Gilchrist, writing in the Folksong Journal, surmises that the song dates from about 1745 when a Manchester regiment was raised to support the Jacobite cause. A broadside version of it was printed by Catnach under the title of The Soldier's Farewell to Manchester.

The Bold Richard — E. J. Moeran recorded this song from James Sutton, 'Old Larpin', of Winterton, Norfolk, in 1915. In a note to the song printed in the Folksong Journal, Ann Gilchrist suggests that The Bold Richard is an English adaptation of an American sailor's song which describes the adventures of Paul Jones' ship, Old Richard.

The Press Gang — E. J. Moeran collected this short piece from, Sutton of Winterton, Norfolk, in 1915, and as far as I have been able to ascertain, it appears not to have been collected elsewhere.

Round Cape Horn — This deep-water sailors' song was once a favourite in both the American and British mercantile fleets. I learned it in 1957 from Sam Larner, an 84 year old herring fisherman of Winterton, Norfolk.

Through Moorfields — Bishop Percy, in his preface to The Reliques of English Poetry, expresses surprise that 'the English should have more songs and ballads on the subject of madness than any of their neighbours'. And indeed it is true that Bedlamite songs were fashionable in England for almost two centuries. For most of that period the mentally sick were looked upon as monstrous freaks and a visit to the madhouse was regarded as a legitimate form of recreation and entertainment, not so very different from a visit to the zoo in our own times. The nationwide pre-occupation with madness is reflected in the works of popular songwriters and dramatists from Elizabethan times onwards, and stories similar to the plot of Through Moorfields were stock favourites with novelists like Defoe and Smollett. The old Bethlem Hospital moved from Bishopsgate to Moorfields in 1675.

Homeward Bound — This wry and down-to-earth appraisal of the sailor's status ashore is, in its own way, a model of the English protest song. In the last days of sail it was used both as a shanty and as a forebitter.