|

|

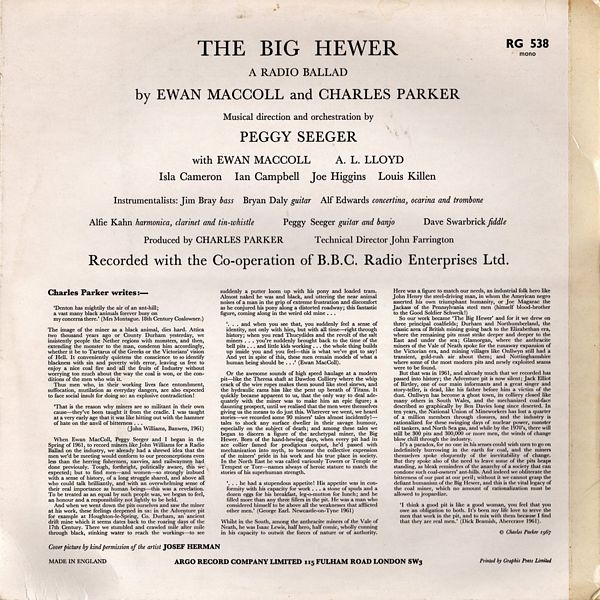

Sleeve Notes

Charles Parker writes: —

'Denton has mightily the air of an ant-hill;

a vast many black animals forever busy on

my concerns there.' (Mrs Montague. 18th Century Coalowner.)

The image of the miner as a black animal, dies hard. Attica two thousand years ago or County Durham yesterday, we insistently people the Nether regions with monsters, and then, extending the monster to the man, condemn him accordingly, whether it be to Tartarus of the Greeks or the Victorians' vision of Hell. It conveniently quietens the conscience to so identify blackness with sin and poverty with error, leaving us free to enjoy a nice coal fire and all the fruits of Industry without worrying too much about the way the coal is won, or the conditions of the men who win it.

Thus men who, in their working lives face entombment, suffocation, mutilation as everyday dangers, are also expected to face social insult for doing so: an explosive contradiction!

'That is the reason why miners are so militant in their own cause — they've been taught it from the cradle. I was taught at a very early age that it was like hitting out with the hammer of hate on the anvil of bitterness …

(John Williams, Banwen, 1961)

When Ewan MacColl, Peggy Seeger and I began in the Spring of 1961, to record miners like John Williams for a Radio Ballad on the industry, we already had a shrewd idea that the men we'd be meeting would conform to our preconceptions even less than the herring fishermen, navvies, and railwaymen had done previously. Tough, forthright, politically aware, this we expected; but to find men — and women — so strongly imbued with a sense of history, of a long struggle shared, and above all who could talk brilliantly, and with an overwhelming sense of their real importance as human beings — this was a revelation. To be treated as an equal by such people was, we began to feel, an honour and a responsibility not lightly to be held.

And when we went down the pits ourselves and saw the miner at his work, these feelings deepened in us: in the Adventure pit for example at Houghton-le-Spring, Co. Durham, an ancient drift mine which it seems dates back to the roaring days of the 17th Century. There we stumbled and crawled mile after mile through black, stinking water to reach the workings — to see suddenly a putter loom up with his pony and loaded tram. Almost naked he was and black, and uttering the near animal noises of a man in the grip of extreme frustration and discomfort as he conjured his pony along a distorted roadway; this fantastic figure, coming along in the weird old mine …

' … and when you see that, you suddenly feel a sense of identity, not only with him, but with all time — right through history; when you read Thucydides and the revolt of the salt miners … you're suddenly brought back to the time of the bell pits … and little kids working … the whole thing builds up inside you and you feel — this is what we've got to say! And yet in spite of this, these men remain models of what a human being should be … ' (Ewan MacColl).

Or the awesome sounds of high speed haulage at a modern pit — like the Theresa shaft at Dawdon Colliery where the whip crack of the wire ropes makes them sound like steel sinews, and the hydraulic rams hiss like the pent up breath of Titans. It quickly became apparent to us, that the only way to deal adequately with the miner was to make him an epic figure; a daunting prospect, until we realised that the men were themselves giving us the means to do just this. Wherever we went, we heard stories — we recorded some 90 miners* tales almost incidently! — tales to shock any surface dweller in their savage humour, especially on the subject of death; and among these talcs we began to discern a figure of the archetypal miner, the Big Hewer. Born of the hand-hewing days, when every pit had its ace collier famed for prodigious output, he'd passed with mechanization into myth, to become the collective expression of the miners' pride in his work and his true place in society. In the North East he was called variously Towers or Temple or Tempest or Torr — names always of heroic stature to match the stories of his superhuman strength.

' … he had a stupendous appetite! His appetite was in conformity with his capacity for work … a stone of spuds and a dozen eggs for his breakfast, leg-o-mutton for lunch; and he filled more than any three fillers in the pit. He was a man who considered himself to be above all the weaknesses that afflicted other men.' (George Earl. Newcastle-on-Tyne 1961)

Whilst in the South, among the anthracite miners of the Vale of Neath, he was Isaac Lewis, half hero, half comic, wholly cunning in his capacity to outwit the forces of nature or of authority. Here was a figure to match our needs, an industrial folk hero like John Henry the steel-driving man, in whom the American negro asserted his own triumphant humanity, or Joe Magarac the Jackass of the Pennsylvania steel men (himself blood-brother to the Good Soldier Schweik!)

So our work became 'The Big Hewer' and for it we drew on three principal coalfields; Durham and Northumberland, the classic area of British mining going back to the Elizabethan era, where the remaining pits must strike deeper and deeper to the East and under the sea; Glamorgan, where the anthracite miners of the Vale of Neath spoke for the runaway expansion of the Victorian era, and mining villages like Onllwyn still had a transient, gold-rush air about them; and Nottinghamshire where some of the most modern pits and newly exploited scams were to be found.

But that was in 1961, and already much that we recorded has passed into history; the Adventure pit is now silent; Jack Elliot of Birtley, one of our main informants and a great singer and story-teller, is dead, like his father before him a victim of the dust. Onllwyn has become a ghost town, its colliery closed like many others in South Wales, and the mechanized coal-face described so graphically by Ben Davies long since deserted. In ten years, the National Union of Mineworkers has lost a quarter of a million members through closures, and the industry is rationalized for these swinging days of nuclear power, monster oil tankers, and North Sea gas, and while by the 1970's, there will still be 300 pits and 300,000 or more men, the winds of change blow chill through the industry.

It's a paradox, for no one in his senses could wish men to go on indefinitely burrowing in the earth for coal, and the miners themselves spoke eloquently of the inevitability of change. But they spoke also of the need to leave some of the pits heaps standing, as bleak reminders of the anarchy of a society that can condone such coal-owners' ant-hills. And indeed we obliterate the bitterness of our past at our peril; without it we cannot grasp the defiant humanism of the Big Hewer, and this is the vital legacy of the coal miner, which no amount of rationalization must be allowed to jeopardize.

'I think a good pit is like a good woman, you feel that you owe an obligation to both. It's been my life love to serve the men that work in the pit, and to mix with them because I find that they are real men.' (Dick Beamish, Abercrave 1961).

© Charles Parker 1967