|

|

|

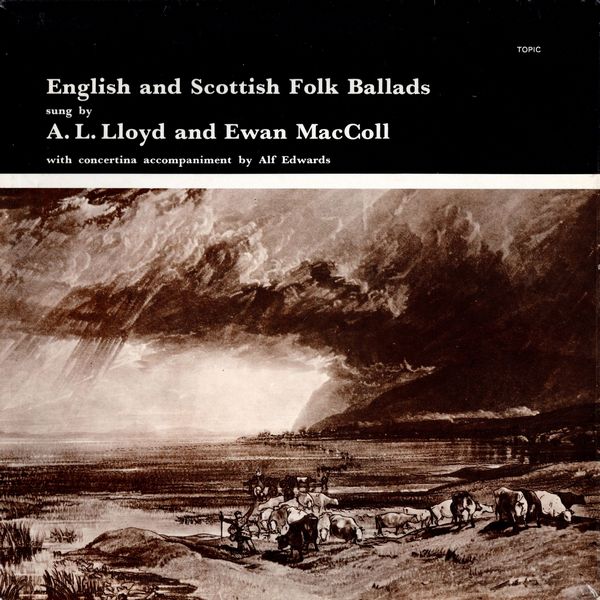

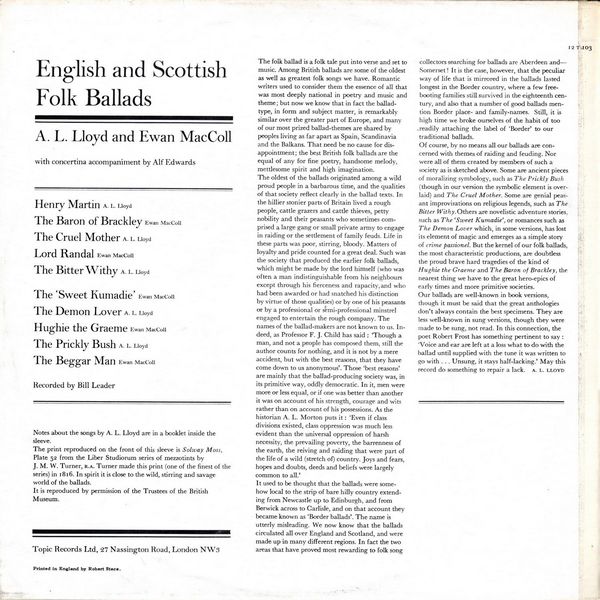

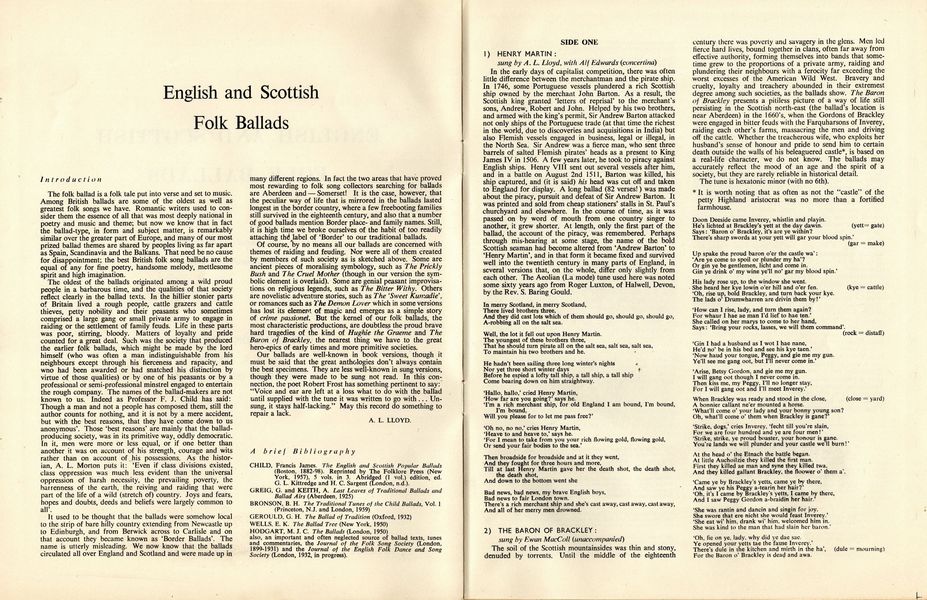

Sleeve Notes

Introduction

The folk ballad is a folk tale put into verse and set to music. Among British ballads are some of the oldest as well as greatest folk songs we have. Romantic writers used to consider them the essence of all that was most deeply national in poetry and music and theme; but now we know that in fact the ballad type, in form and subject matter, is remarkably similar over the greater part of Europe, and many of our most prized ballad themes are shared by peoples living as far apart as Spain, Scandinavia and the Balkans. That need be no cause for disappointment; the best British folk ballads are the equal of any for fine poetry, handsome melody, mettlesome spirit and high imagination.

The oldest of the ballads originated among a wild proud people in a barbarous time, and the qualities of that society reflect clearly in the ballad texts. In the hillier stonier parts of Britain lived a rough people, cattle grazers and cattle thieves, petty nobility and their peasants who sometimes comprised a large gang or small private army to engage in raiding or the settlement of family feuds. Life in these parts was poor, stirring, bloody. Matters of loyalty and pride counted for a great deal. Such was the society that produced the earlier folk ballads, which might be made by the lord himself (who was often a man indistinguishable from his neighbours except through his fierceness and rapacity, and who had been awarded or had snatched his distinction by virtue of those qualities) or by one of his peasants or by a professional or semi-professional minstrel engaged to entertain the rough company. The names of the ballad-makers are not known to us. Indeed, as Professor F. J. Child has said: 'Though a man and not a people has composed them, still the author counts for nothing, and it is not by a mere accident, but with the best reasons, that they have come down to us anonymous'. Those 'best reasons' are mainly that the ballad producing society was, in its primitive way, oddly democratic. In it, men were more or less equal, or if one was better than another it was on account of his strength, courage and wits rather than on account of his possessions. As the historian A. L. Morton puts it: 'Even if class divisions existed, class oppression was much less evident than the universal oppression of harsh necessity, the prevailing poverty, the barrenness of the earth, the reiving and raiding that were part of the life of a wild (stretch of) country. Joys and fears, hopes and doubts, deeds and beliefs were largely common to all'.

It used to be thought that the ballads were somehow local to the strip of bare hilly country extending from Newcastle up to Edinburgh, and from Berwick across to Carlisle, and on that account they became known as 'Border Ballads'. The name is utterly misleading.

We now know that the ballads circulated all over England and Scotland, and were made up in many different regions. In fact the two areas that have proved most rewarding to folk song collectors searching for ballads are Aberdeen and — Somerset!

It is the case, however, that the peculiar way of life that is mirrored in the ballads lasted longest in the Border country, where a few free-booting families still survived in the eighteenth century, and also that a number of good ballads mention Border place and family names. Still, it is high time we broke ourselves of the habit of too readily attaching the label of 'Border' to our traditional ballads.

Of course, by no means all our ballads are concerned with themes of raiding and feuding. Nor were all of them created by members of such a society as is sketched above. Some are ancient pieces of moralizing symbology, such as The Prickly Bush (though in our version the symbolic element is overlaid) and The Cruel Mother. Some are genial peasant improvisations on religious legends, such as The Bitter Withy. Others are novelistic adventure stories, such as The 'Sweet Kumadie', or romances such as The Demon Lover which, in some versions, has lost its element of magic and emerges as a simple story of crime passionel. But the kernel of our folk ballads, the most characteristic productions, are doubtless the proud brave hard tragedies of the kind of Hughie the Graeme and The Baron of Brackley, the nearest thing we have to the great hero-epics of early times and more primitive societies.

Our ballads are well known in book versions, though it must be said that the great anthologies don't always contain the best specimens. They are less well known in sung versions, though they were made to be sung, not read. In this connection, the poet Robert Frost has something pertinent to say: "Voice and ear are left at a loss what to do with the ballad until supplied with the tune it was written to go with … Unsung, it stays half-lacking." May this record do something to repair a lack.

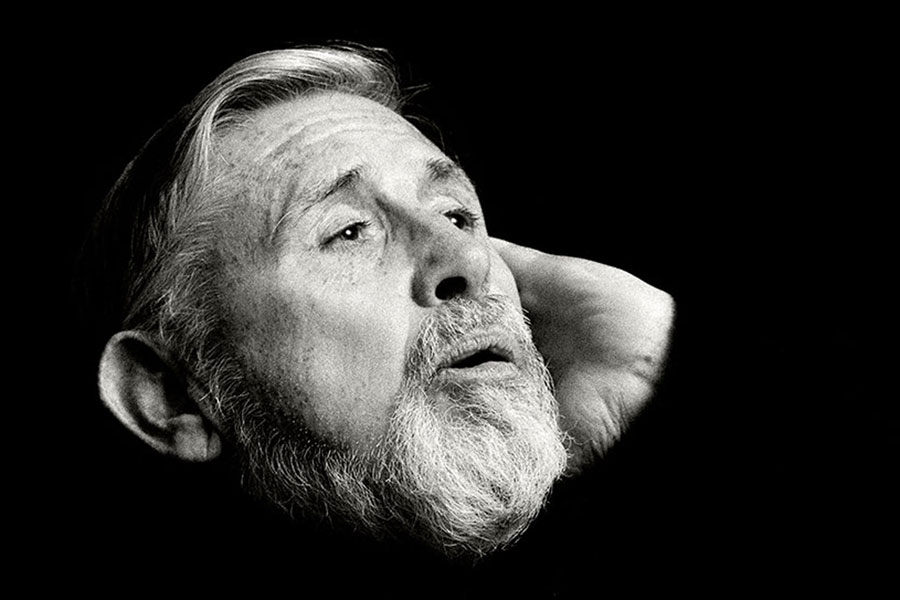

A. L. LLOYD

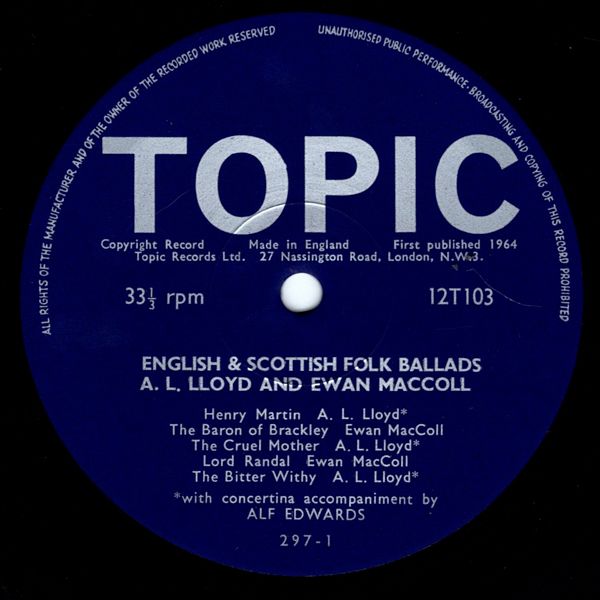

Henry Martin: Sung by A. L. Lloyd, with Alf Edwards (concertina) — In the early days of capitalist competition, there was often little difference between the merchantman and the pirate ship. In 1746, some Portuguese vessels plundered a rich Scottish ship owned by the merchant John Barton. As a result, the Scottish king granted 'letters of reprisal' to the merchant's sons, Andrew, Robert and John. Helped by his two brothers, and armed with the king's permit, Sir Andrew Barton attacked not only ships of the Portuguese trade (at that time the richest in the world, due to discoveries and acquisitions in India) but also Blemish vessels engaged in business, legal or illegal, in the North Sea. Sir Andrew was a fierce man, who sent three barrels of salted Blemish pirates' heads as a present to King James IV in 1506. A few years later, he took to piracy against English ships. Henry VIII sent out several vessels after him, and in a battle on August 2nd, 1511, Barton was killed, his ship captured, and (it is said) his head was cut off and taken to England for display. A long ballad (82 verses!) was made about the piracy, pursuit and defeat of Sir Andrew Barton.

It was printed and sold from cheap stationers' stalls in St. Paul's churchyard and elsewhere. In the course of time, as it was passed on by word of mouth from one country singer to another, it grew shorter. At length, only the first part of the ballad, the account of the piracy, was remembered. Perhaps through mis-hearing at some stage, the name of the bold Scottish seaman had become altered from Andrew Barton' to 'Henry Martin', and in that form it became fixed and survived well into the twentieth century in many parts of England, in several versions that, on the whole, differ only slightly from each other. The Aeolian (La mode) tune used here was noted some sixty years ago from Roger Luxton, of Halwell, Devon, by the Rev. S. Baring Gould.

The Baron of Brackley: Sung by Ewan MacColl (unaccompanied) — The soil of the Scottish mountainsides was thin and stony, denuded by torrents. Until the middle of the eighteenth century there was poverty and savagery in the glens. Men led fierce hard lives, bound together in clans, often far away from effective authority, forming themselves into bands that sometime grew to the proportions of a private army, raiding and plundering their neighbours with a ferocity far exceeding the worst excesses of the American Wild West. Bravery and cruelty, loyalty and treachery abounded in their extremest degree among such societies, as the ballads show. The Baron of Brackley presents a pitiless picture of a way of life still persisting in the Scottish north-east (the ballad's location is near Aberdeen) in the 1660s when the Gordons of Brackley were engaged in bitter feuds with the Farquharsons of Inverey, raiding each other's farms, massacring the men and driving off the cattle. Whether the treacherous wife, who exploits her husband's sense of honour and pride to send him to certain death outside the walls of his beleaguered castle* is based on a real life character, we do not know. The ballads may accurately reflect the mood of an age and the spirit of a society, but they are rarely reliable in historical detail.

The tune is hexatonic minor (with no 6th).

* It is worth noting that as often as not the 'castle' of the petty Highland aristocrat was no more than a fortified farmhouse.

The Cruel Mother: Sung by A. L. Lloyd, with Alf Edwards (concertina) — The ballad seems to be old, for it is full of primitive folklore notions such as the knife from which blood can never be washed (the instance of Lady Macbeth comes to mind). Also primitive is the idea that the dead who have not undergone the ceremony that initiates them fully into the world of the living (in this case, christening) can never be properly received and incorporated into the world of the dead, but must return to plague the living. Some scholars think The Cruel Mother may have been brought to England by invading Norsemen, since practically the same story occurs in Danish balladry (Little Kirsten gives birth to twins in the woods; she hides them under a stone; eight years later they return from the gates of the land of the dead to confront her; she fails to recognise them until they re-tell the story of her crime; she tries to please them with gifts but they curse her and she is doomed to hell-fire). Verse by verse, the Danish sets of the ballad so closely resemble the English that it seems unlikely that the importation took place so long ago. More probably, it is a case of an ancient folk tale being turned into a lyrical ballad, perhaps within the last four hundred years, and spreading in various parts of Europe, possibly with the help of printed versions all deriving from a single original (whether that original was English or Danish or in some other language, our present researches do not tell us). The terrible story has had a particular fascination for children and the ballad became a game song. A folklorist saw the game being played in a Lancashire orphanage in 1915. The children called it The Lady Drest in Green. (There was a lady drest in green, / Fair a lair a lido, / There was a lady drest in green, / Down by the greenwood side, o). The song describes how the lady kills her baby with a penknife, tries to wash off the blood, goes home to lie down, is aroused by three 'bobbies' at the door, who extract a confession from her and rush her off to prison, and 'That was the end of Mrs. Green'. It is a ring game. Two children in the middle impersonate Mrs. Green and the baby, following the action of the song. The children in the ring dance around, singing the refrains, until the 'bobbies' rush in and seize the mother, when the ring breaks up. In his London Street Games (1931 ed.), Norman Douglas prints a corrupt version current in East and South-east London during the First World War. The ballad has remained a great favourite and is still to be heard from country singers all over the British Isles and America (where sometimes the event is given a railway setting, 'down by old Greenwood Siding'). The Dorian (Re-mode) tune we use was obtained by H. E .D. Hammond from Mrs. Bowring, of Cerne Abbas, Dorset. It is printed in The Penguin Book of English Folk Songs, ed. R. Vaughan Williams and A. L. Lloyd (1959).

Lord Randal: Sung by Ewan MacColl (unaccompanied) — This is one of the most widespread of all European ballads, known in Italy, Germany, Holland, the Scandinavian countries (including Iceland), also in Czechoslovakia and Hungary. It has been particularly common in Britain (Sharp noted seventeen versions of it in Somerset alone: though curiously enough Gavin Greig, who collected several hundred ballads in the folkloristically rich parish of New Deer, Aberdeenshire, found only four versions of Lord Ronald — as many Scottish singers prefer to call it — and two of these he describes as 'very fragmentary').

It is possible that the ballad began its life in Italy, where it was printed on a Veronese broadside dated 1629 under the title of L'Avvelenato (The Poisoned One). There is no sure trace of the ballad in Britain before the closing years of the eighteenth century, in Johnson's Scots Musical Museum (1787-1803), to which Burns contributed several Scottish folk songs. Sir Walter Scott thought that the ballad may originally have concerned the death of Thomas Randal, Earl of Murray and nephew to Robert Bruce, who died at Musselburgh in 1332. This is sheer guesswork of the kind that early ballad scholars liked to indulge in. There is not even evidence that Sir Thomas Randal was poisoned. In the mid-nineteenth century, Lord Randal was made into a Cockney burlesque song much favoured by stage comedians, and in its comic form it may still be heard among schoolchildren in the poorer parts of London.

The melody used by Ewan MacColl (learnt from his mother, of Perthshire origin) is of major-minor character with mixolydian inflections, due to its fluctuating 3rd and 7th steps. Some of the Scottish Lord Randal tunes are forms of the well known Villikens and his Dinah melody, and it is possible that Ewan MacColl's tune is a distant and colourful cousin of the same humble family.

The Bitter Withy: Sung by A. L. Lloyd with Alf Edwards (concertina) — English country folk in the past showed themselves to be attracted to many 'unofficial' scriptural legends, notably to those that depicted Biblical characters acting like European rustics, and most particularly to those that held an element of social protest or at least of egalitarianism. Thus, for instance, in the famous Cherry Tree Carol, Joseph speaks like a true peasant husband when he and his pregnant wife are making their way through the orchard, and Mary asks him to gather her some cherries, and we are told:

Up then spoke Joseph, with words rude and wild:

'Let him gather thee cherries that put thee with child.'

The Bitter Withy carol is likewise peopled with figures out of the rural landscape of medieval England — the child playing ball in the street, the snobbish young rich boys who scorn him, the rich young mothers who run with their tale of disaster, and the angry mother who chastises her child by laying him across her knee and thrashing him. The Bitter Withy (a carol without any connection with Christmas) remained one of the most favoured of English religious folk songs until very recent years, perhaps on account of its social content; the fact that in it, the snobbish young lords receive their 'comeuppance' at the hands of the Infant Jesus seems to have endeared the carol to countless generations of humble singers. The tradition of Jesus supporting himself on a sunbeam, and his companions trying to do so and fatally falling, is to be found in the Apocryphal Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, and also in a 13th Century English manuscript containing rhymed legends of the life of Jesus. A fresco in the church of San Martino in Lucca, Italy, shows the Virgin Mary chastising the young Jesus (though when the surrealist painter Max Ernst painted a similar scene in the early 1930s, the French authorities impounded his picture as being blasphemous). The incident of Christ's cursing the willow in the last verse, is no doubt a folklorish attempt to explain a natural phenomenon: it is a fact that the willow is very prone to 'perish at the heart'. The carol seems to have survived best in Hereford and Shropshire, where Vaughan Williams obtained more than half a dozen versions in 1908-9. The present tune is hexachordal (consisting of six adjacent steps) and of major character.

The Sweet Kumadie: Sung by Ewan MacColl with Alf Edwards (concertina) — This very favourite ballad seems to have reached the height of its popularity in the seventeenth century, but English country singers went on singing it for another two hundred years, and during that time it crossed the border into Scotland and spread at least as far as Aberdeen in sundry shapes and to various tunes.

Among his collection of ballad sheets, Samuel Pepys had a broadside of it, printed in the 1680s. In his version, the villainous captain is identified as Sir Walter Raleigh, and the ballad starts:

Sir Walter Raleigh has built a ship,

In the Neatherlands.

Sir Walter Raleigh has built a ship,

In the Neatherlands.

And it is called The Sweet Trinity,

And was taken by the false gallaly.

Sailing in the Lowlands.

In his time, Raleigh was no favourite with the common people, who considered him arrogant, selfish, an upstart, heartless to those beneath him. The ballad-story is sheer fiction but it corresponds to the popular view of Raleigh in his lifetime and for many decades after. Gradually, however, the character of Raleigh faded, his name dropped out of the ballad. Likewise the name of the ship, Sweet Trinity; became altered to Holy Trinity; Golden Vanity Golden Victory (in Nelson's time), Yellow Golden Tree, Sweet Willow Tree, Sweet Kumadie, and others. The enemy is sometimes unspecified, sometimes French, sometimes Turkish. The fate of the brave little cabin boy is also various, according to the emotional preference of the singer. Sometimes the boy is well rewarded; in other versions he is left to drown; in others still he is picked up, dies on deck, is sewn in cowhide and thrown overboard. In the present version, the cowhide motif is misplaced and the cabin boy wears it as a kind of bathing costume. In some English versions, the boy dives overboard in his 'stark bare skin'. This got changed by one sailor singer into 'black bear skin'. The singer explained that this was the boy's covering at night and he wished to wear it as a disguise while in the water.

The tune is hexatonic major (no 7th).

The Demon Lover: Sung by A. L. Lloyd (unaccompanied) — In the 17th century a very popular ballad was printed by several broadside publishers, entitled: A Warning for Married Women, being an example of Mrs. Jane Reynolds (a West country woman), born near Plymouth, who, having plighted her troth to a Seaman, was afterwards married to a Carpenter, and at last carried away by a Spirit, the manner how shall be presently recited.' To a West country tune called 'The Fair Maid of Bristol', 'Bateman', or 'John True'. Samuel Pepys had this one in his collection also. It was a longish ballad (32 verses) but a very poor composition made by some hack poet. Perhaps the doggerel writer made his version on the basis of a fine ballad already current among folk singers. Or perhaps the folk singers took the printed song and in the course of passing it on from mouth to mouth over the years and across the shires they reshaped it into something of pride, dignity and terror. Whatever the case, the ballad has come down to us in far more handsome form than Pepys had it. Though very rarely met with nowadays, it was formerly well known in Scotland as well as in England. For instance, Walter Scott included a good version in his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1812 edn.) Generally the Scottish texts of this ballad are better than the English ones, none of which tell the full story (we have filled out our version by borrowing some stanzas from Scottish sets of the ballad), but none of the Scottish tunes for it are as good as those found in the South and West of England. Our present tune was noted by H. E. D. Hammond from Mrs. Russell of Upway, near Dorchester, Dorset, in 1907. Cecil Sharp considered it 'one of the finest Dorian airs' he had seen. Dr. Vaughan Williams made a splendid choral setting of the opening verses of this ballad, which he called: The Lover's Ghost.

Hughie The Graeme: Sung by Ewan MacColl with Alf Edwards (concertina) — We do not know if Hugh Graeme, the border raider, is a figure of history or fiction. Several versions of the ballad set the scene of his plundering activities in the neighbourhood of Carlisle, and we are reminded that in 1548, complaints were laid to the Lord Bishop of Carlisle against more than four hundred freebooters and outlaws, of whom Hugh may have been one. The present version places the action further north, in the neighbourhood of 'Strievelin toun' (Stirling), but as with the Border versions, the sympathies are all with the bad man and all against the authorities. Hugh was perhaps unusually well-favoured in having the Earl of Home's wife to speak up for him, though her intervention was fruitless. The earliest printed form of the ballad appears — a little surprisingly perhaps — in the compilation of mainly saucy songs known as Durfey's Pills to Purge Melancholy (1720), but it was already quite an old song then. Once common, the ballad seems to have become very rare in tradition. Only one version is reported in the twentieth century, obtained by the diligent Scottish collector Gavin Greig from Mrs. Lyall of Skene, near Aberdeen. Mrs. Lyall's excellent Dorian tune is the one used here by Ewan MacColl.

The Prickly Bush: Sung by A. L. Lloyd with Alf Edwards (concertina) — In the opinion of many scholars this is among the oldest, most typical and most interesting of ballads. It has turned up in countless versions in the Scandinavian and Baltic countries, in Central Europe, Hungary, Rumania and Russia, and the ballad specialist Francis J. Child considered that the best version of all is Sicilian. It has enjoyed very wide currency in the British Isles and also in the USA, where it has been described as 'easily the favourite of all the traditional ballads among the Negroes'. In many versions, the story tells of a young woman captured by pirates or brigands; father, mother, brother, sister, refuse to pay ransom, but the lover sets her free. In earlier forms of the ballad, the girl is condemned to die for the loss of a golden ball (or golden key, either signifying the girl's honour which, when lost, can only be restored by her lover.) There is a folk tale, once well known in England in which a stranger gives a girl a golden ball. If she loses it, she is to be hanged. While playing with the ball she does lose it. At the gallows, her kindred refuse to help, but the lover recovers the ball after terrible adventures in the house of ill-omen where it had rolled. It seems that verses of The Prickly Bush (also called The Maid Freed from the Gallows) were sung in the course of telling the story. The losing of the golden ball and the subsequent scene at the gallows used to form a children's game in Lancashire in the 19th century, again accompanied by the song. In Missouri, the song is used as part of a story of a Negro girl with a magic golden ball that will make her white. From a similar cante-fable, the admired Negro singer Huddie Ledbetter (Leadbelly) evolved a version that became well known after it appeared on a commercial disc. Many layers of folklore, extending to very primitive times, may be revealed by deep study of this ancient ballad, in which, at some stage in certain versions, the condemned person has changed sex and become a man who is freed by his girlfriend.

The form of the ballad is likewise interesting. It is frequently suggested that the ballads originated as choral dances. That is, a group formed a ring and danced round. A member of the group sang a single line or set of lines, and the rest came in with a refrain. It has been further suggested that ballads were actually created in the course of this operation, with various members of the group improvising sequences (alternated with refrain) until the ballad story was carried to a conclusion. Now, not many ballads, as we know them, show signs of this kind of communal creation. But The Prickly Bush, with its extremely simple construction, may well have come into being in such a way. Few ballads show such clear signs of a primitive dramatic structure as this one, though the major tune, collected by Lucy Broadwood in Buckinghamshire, is probably fairly modern.

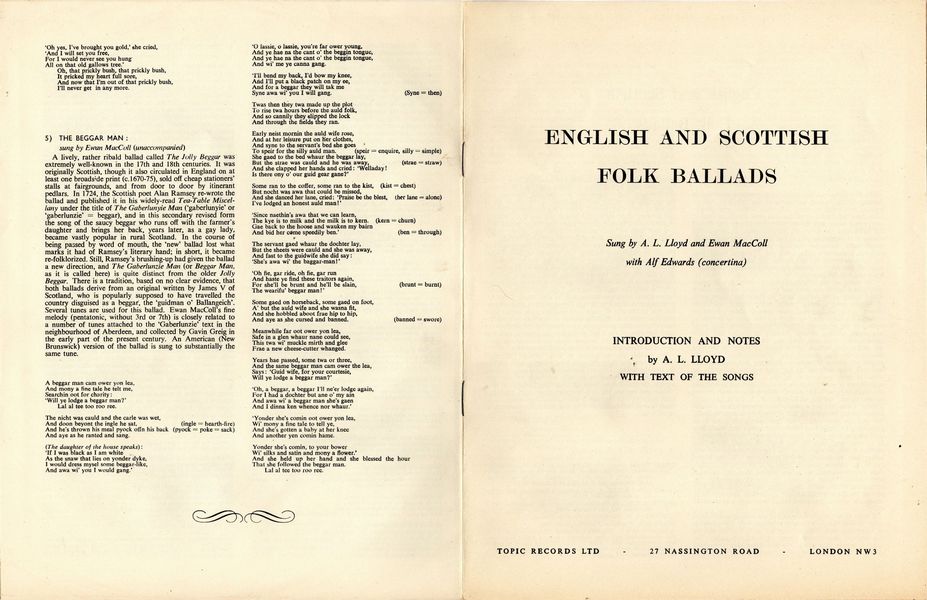

The Beggar Man: Sung by Ewan MacColl (unaccompanied) — A lively, rather ribald ballad called The Jolly Beggar was extremely well known in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was originally Scottish, though it also circulated in England on at least one broadside print (c. 1670-75), sold off cheap stationers' stalls at fairgrounds, and from door to door by itinerant pedlars. In 1724, the Scottish poet Alan Ramsey re-wrote the ballad and published it in his widely read Tea-Table Miscellany under the title of The Gaberlunyie Man ('gaberlunyie' or 'gaberlunzie' = beggar), and in this secondary revised form the song of the saucy beggar who runs off with the farmer's daughter and brings her back, years later, as a gay lady, became vastly popular in rural Scotland. In the course of being passed by word of mouth, the 'new' ballad lost what marks it had of Ramsey's literary hand; in short, it became re-folklorized. Still, Ramsey's brushing up had given the ballad a new direction and The Gaberlunzie Man (or Beggar Man, as it is called here) is quite distinct from the older Jolly Beggar There is a tradition, based on no clear evidence, that both ballads derive from an original written by James V of Scotland, who is popularly supposed to have travelled the country disguised as a beggar, the 'guidman o' Ballangeich'. Several tunes are used for this ballad. Ewan MacColl's fine melody (pentatonic, without 3rd or 7th) is closely related to a number of tunes attached to the 'Gaberlunzie' text in the neighbourhood of Aberdeen, and collected by Gavin Greig in the early part of the present century. An American (New Brunswick) version of the ballad is sung to substantially the same tune.