|

|

Sleeve Notes

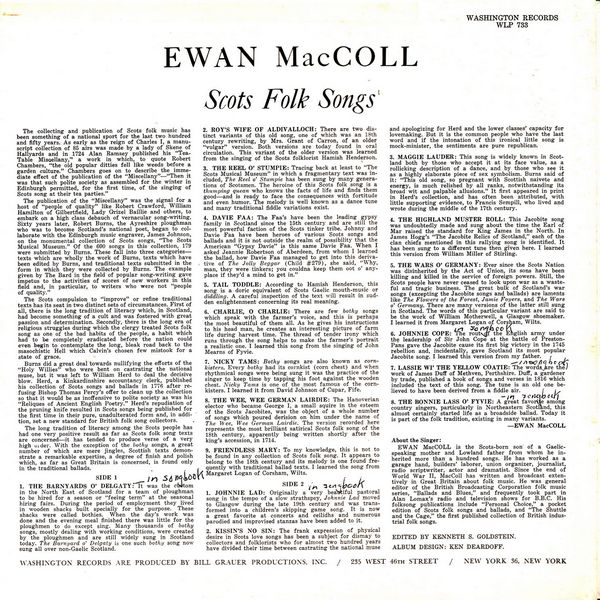

The collecting and publication of Scots folk music has been something of a national sport for the last two hundred and fifty years. As early as the reign of Charles I, a manuscript collection of 85 airs was made by a lady of Skene of Hallyards and in 1724 Alan Ramsey published his "Tea-Table Miscellany," a work in which, to quote Robert Chambers, "the old popular ditties fell like weeds before a garden culture." Chambers goes on to describe the immediate effect of the publication of the "Miscellany" — "Then it was that such polite society as assembled for the winter in Edinburgh permitted, for the first time, of the singing of Scots song at their tea parties."

The publication of the "Miscellany" was the signal for a host of "people of quality" like Robert Crawford, William Hamilton of Gilbertfield, Lady Grizel Baillie and others, to embark on a high class debauch of vernacular song-writing. Sixty years later, Robert Burns, the Ayreshire ploughman who was to become Scotland's national poet, began to collaborate with the Edinburgh music engraver, James Johnson, on the monumental collection of Scots songs, "The Scots Musical Museum." Of the 600 songs in this collection, 179 were submitted by Burns. These fall into three categories — texts which are wholly the work of Burns, texts which have been edited by Burns, and traditional texts submitted in the form in which they were collected by Burns. The example given by The Bard in the field of popular song-writing gave impetus to the activities of scores of new workers in this field and, in particular, to writers who were not "people of quality."

The Scots compulsion to "improve" or refine traditional texts has its seat in two distinct sets of circumstances. First of all, there is the long tradition of literacy which, in Scotland, had become something of a cult and was fostered with great passion and determination. Secondly, there is the long era of religious struggles during which the clergy treated Scots folk song as one of the bad habits of the people, a habit which had to be completely eradicated before the nation could even begin to contemplate the long, bleak road back to the masochistic Hell which Calvin's chosen few mistook for a state of grace.

Burns did a great deal towards nullifying the efforts of the "Holy Willies" who were bent on castrating the national muse, but it was left to William Herd to deal the decisive blow. Herd, a Kinkardinshire accountancy clerk, published his collection of Scots songs and ballads in 1776 after refusing Bishop Thomas Percy's offer to clean up the collection so that it would be as inoffensive to polite society as was his "Reliques of Ancient English Poetry." Herd's repudiation of the pruning knife resulted in Scots songs being published for the first time in their pure, unadulterated form and, in addition, set a new standard for British folk song collectors.

The long tradition of literacy among the Scots people has had one very positive result as far as Scots folk song texts are concerned-it has tended to produce verse of a very high wider. With the exception of the bothy songs, a great number of which are mere jingles, Scottish texts demonstrate a remarkable expertise, a degree of finish and polish which, as far as Great Britain is concerned, is found only in the traditional ballads.

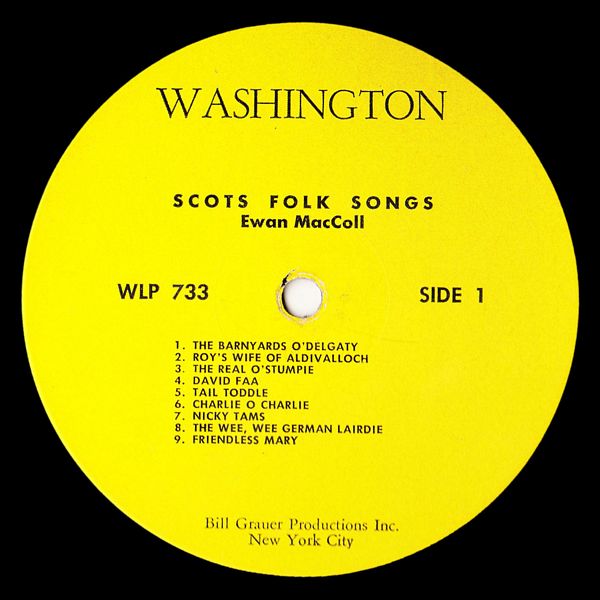

THE BARNYARDS O DELGATY

It was the custom in the North East of Scotland for a team of ploughman to be hired for a season or "feeing term" at the seasonal hiring fairs. During the period of employment they lived in wooden shacks built specially for the purpose. These shacks were called bothies. When the day's work was done and the evening meal finished there was little for the ploughmen to do except sing. Many thousands of bothy songs, mostly dealing with working conditions, were created by the ploughmen and are still widely sung in Scotland today. The Barnyard o' Delgaty is one such bothy song now sung all over non-Gaelic Scotland.

ROY'S WIFE OF ALDIVALLOCH

There are two distinct variants of this old song, one of which was an 18th century rewriting, by Mrs. Grant of Carron, of an older "vulgar" version. Both versions are today found in oral circulation. This variant of the older version was learned from the singing of the Scots folklorist Hamish Henderson.

THE REEL O' STUMPIE

Tracing back at least to "The Scots Musical Museum" in which a fragmentary text was included, The Reel o' Stumpie has been sung by many generations of Scotsmen. The heroine of this Scots folk song is a thumping quean who knows the facts of life and finds them good — and is ready to face the consequences with fortitude and even humor. The melody is well known as a dance tune and many traditional fiddle variations exist.

DAVIE FAA

The Faa's have been the leading gypsy family in Scotland since the 15th century and are still the most powerful faction of the Scots tinker tribe. Johnny and Davie Faa have been heroes of various Scots songs and ballads and it is not outside the realm of possibility that the American "Gypsy Davie" is this same Davie Faa. When I asked Jeannie Robertson of Aberdeen, from whom I learned the ballad, how Davie Faa managed to get into this derivative of The Jolly Beggar (Child #279), she said, "Why, man, they were tinkers; you couldna keep them oot o' any-place if they'd a mind to get in."

TAIL TODDLE

According to Hamish Henderson, this song is a doric equivalent of Scots Gaelic mouth-music or diddling. A careful inspection of the text will result in sudden enlightenment concerning its real meaning.

CHARLIE, O CHARLIE

There are few bothy songs which speak with the farmer's voice, and this is perhaps the most beautiful of them all. As he gives his instructions to his head man, he creates an interesting picture of farm life during harvest time. The thread of tender irony which runs through the song helps to make the farmer's portrait a realistic one. I learned this song from the singing of John Mearns of Fyvie.

NICKY TAMS

Bothy songs are also known as cornkisters. Every bothy had its cornkist (corn chest) and when rhythmical songs were being sung it was the practice of the singer to keep time by tapping his foot against the wooden chest. Nicky Tams is one of the most famous of the cornkisters. I learned it from David Johnson of Cupar, Fife.

THE WEE, WEE GERMAN LAIRDIE

The Hanoverian elector who became George I, a small squire in the esteem of the Scots Jacobites, was the object of a whole number of songs which poured derision on him under the name of The Wee, Wee German Lairdie. The version recorded here represents the most brilliant satirical Scots folk song of the 18th century, apparently being written shortly after the king's accession, in 1714.

FRIENDLESS MARY

To my knowledge, this is not to be found in any collection of Scots folk song. It appears to belong to the 18th century and its melody is one found frequently with traditional ballad texts. I learned the song from Margaret Logan of Corsham, Wilts.

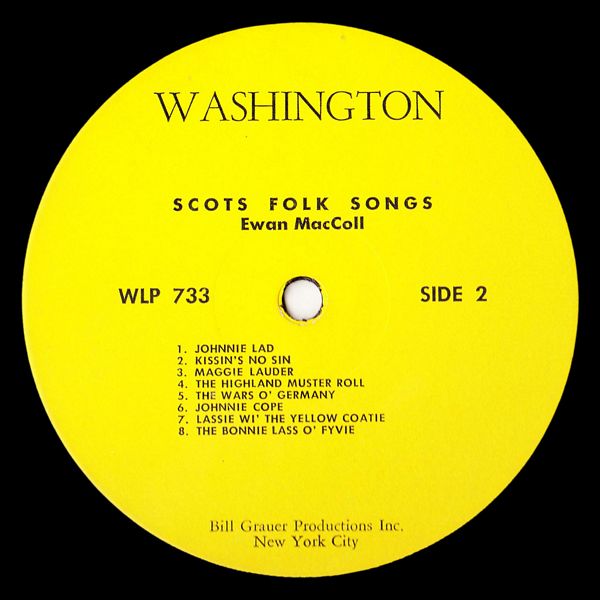

JOHNNIE LAD

Originally a very beautiful pastoral song in the tempo of a slow strathspey, Johnnie Lad moved to Glasgow during the late 19th century and was transformed into a children's skipping game song. It is now a great favorite at concerts and ceilidhs and numerous parodied and improvised stanzas have been added to it.

KISSIN'S NO SIN

The frank expression of physical desire in Scots love songs has been a subject for dismay to collectors and folklorists who for almost two hundred years have divided their time between castrating the national muse and apologizing for Herd and the lower classes' capacity for lovemaking. But it is the common people who have the last word and if the intonation of this ironical little song is mock-minister, the sentiments are pure republican.

MAGGIE LAUDER

This song is widely known in Scotland both by those who accept it at its face value, as a rollicking description of a dance, and by those who see it as a highly elaborate piece of sex symbolism. Burns said of it: "This old song, so pregnant with Scottish naiveté and energy, is much relished by all ranks, notwithstanding its broad — wit and palpable allusions." It first appeared in print in Herd's collection, and has often been attributed, with little supporting evidence, to Francis Sempill, who lived and wrote during the middle of the 17th century.

THE HIGHLAND MUSTER ROLL

This Jacobite song was undoubtedly made and sung about the time the Earl of Mar raised the standard for King James in the North. In James Hogg's "The Jacobite Relics of Scotland," each of the clan chiefs mentioned in this rallying song is identified. It has been sung to a different tune then given here. I learned this version from William Miller of Stirling.

THE WARS O' GERMANY

Ever since the Scots Nation was disinherited by the Act of Union, its sons have been killing and killed in the service of foreign powers. Still, the Scots people have never ceased to look upon war as a wasteful and tragic business. The great bulk of Scotland's war songs (excepting the Jacobite songs and ballads) are laments like The Flowers of the Forest, Jamie Foyers, and The Wars o' Germany. There are many versions of the latter still sung in Scotland. The words of this particular variant are said to be the work of William Motherwell, a Glasgow shoemaker. I learned it from Margaret Logan of Corsham, Wilts.

JOHNNIE COPE

The rout of the English army under the leadership of Sir John Cope at the battle of Preston-Pans gave the Jacobite cause its first big victory in the 1745 rebellion and, incidentally, gave Scotland its most popular Jacobite song. I learned this version from my father.

LASSIE WI' THE YELLOW COATIE

The words are the work of James Duff of Methven, Perthshire. Duff, a gardener by trade, published a book of songs and verses in 1816 which included the text of this song. The tune is an old one believed to have been derived from a fiddle air.

THE BONNIE LASS O' FYVIE

A great favorite among country singers, particularly in Northeastern Scotland, this almost certainly started life as a broadside ballad. Today it is part of the folk tradition, existing in many variants.

— EWAN MacCOLL

About the Singer: EWAN MacCOLL is the Scots-born son of a Gaelic-speaking mother and Lowland father from whom he inherited more than a hundred songs. He has worked as a garage hand, builders' laborer, union organizer, journalist, radio scriptwriter, actor and dramatist. Since the end of World War II, MacColl has written and broadcast extensively in Great Britain about folk music. He was general editor of the British Broadcasting Corporation folk music series, "Ballads and Blues," and frequently took part in Alan Lomax's radio and television shows for B.B.C. His folksong publications include "Personal Choice," a pocket edition of Scots folk songs and ballads, and "The Shuttle and the Cage," the first published collection of British industrial folk songs.