|

|

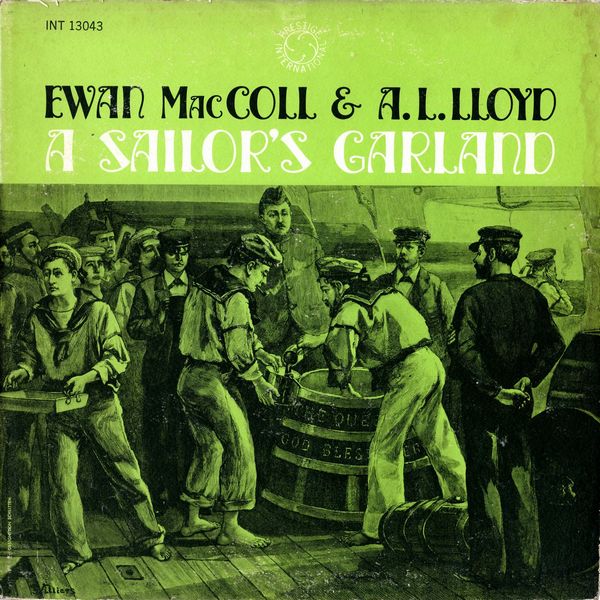

Sleeve Notes

Sailing-ship seamen sang two kinds of songs — forebitters and shanties. Forebitters were sung for fun, off watch, and were any kind of lyrical song, traditional or otherwise, concerned with life at sea or ashore. They were anybody's songs. But the shanties were different. They belonged to the seamen alone, and were never sung for fun. The shanties were sung at work only, to make a hard job go easier and a dull job more palatable. The device is ancient. Over fifteen hundred years ago, Daphnis and Chloe, on the cliffs of their little island, heard the shantyman urging the seamen on with song and "the rest, like a chorus all together, strained their throats to a loud holla and catcht his voice at intervals." It may be that the shanty that echoed across the Aegean to the listening goatherds was not vastly different in form from the songs on this record. Yet these are, by folklore standards, recent songs, evolved during the nineteenth century as a product of capitalism. It seems that, two hundred years ago, shanty-singing had dwindled almost out of earshot. Forebitters were much sung in the foc'sle, but work on deck was mostly synchronized by whistle rather than by song. However, early in the 19th century, faster ships were being built and shipping lines began to develop in fierce competition with each other. Ocean crossings became a race with time and the ships of rival companies. To keep the ships to a tight schedule, skippers were under hard pressure from city men, and they passed this pressure on to the men. It was found that ships could be moved faster if the crew were urged, and their movements synchronized, by song. "A good shantyman's worth two extra hands on the rope," was the saying. So, out of the rivalry of business men came most of the shanties we know nowadays. The songs were of various sorts — with rambling beat and more or less coherent text for the dull continuous task of walking the capstan round, with vehemently pointed rhythm and fragmentary pithy words for the fierce heave-together of raising sail. There were slow sombre songs for the heavy lifts and brisk vivid songs for the stamp-and-go of lighter tasks. The good shantyman had a varied repertory of tunes to fit the required rhythm of each different job, and he had an alert mind for improvising verses to keep the crew in heart during long pulls in hard weather. The great period of shantysinging was a short one, lasting a bare fifty years. Relatively few were heard before 1830, by 1850 the oceans were ringing with them, and by the 1880s their sound had faded again. Steam replaced sail, and shanties have no function when winches do the hauling. Yet the power of the shanties has long outlived the times that gave them rise, just as the great folk ballads have outlived the days of border raid and blood feud. The sight of a sailing ship is rare now, but the shanties still have it in them, as few songs have, to move us by their elemental music, their rough poetry, and the convincing picture they give of a brave and bitter way of life.

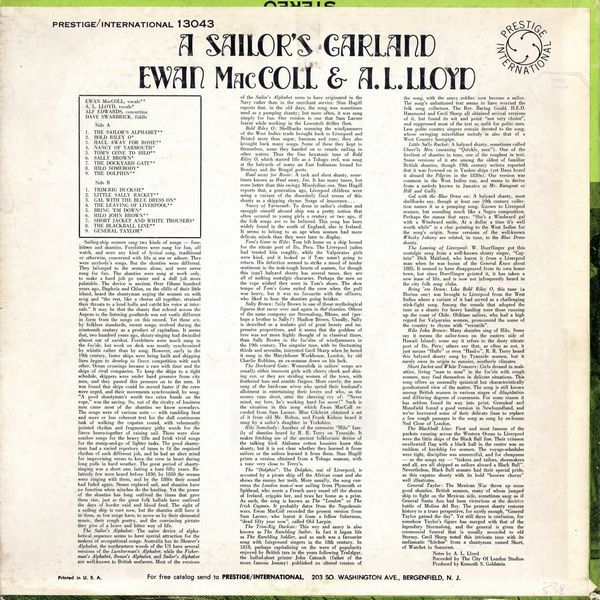

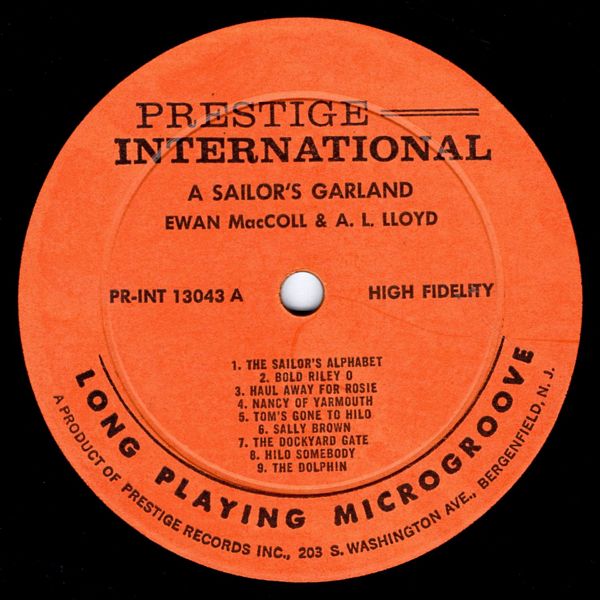

The Sailors Alphabet: The naive device of alphabetical sequence seems to have special attraction for the makers of occupational songs. Australia has its Shearer's Alphabet, the northeastern woods of the US have several versions of the Lumberman's Alphabet, while the Fisherman's Alphabet, Bosun's Alphabet, and Sailor's Alphabet are well-known to British seafarers. Most of the versions of the Sailor's Alphabet seem to have originated in the Navy rather than in the merchant service. Stan Hugill reports that, in the old days, the song was sometimes used as a pumping shanty; hut more often, it was sung simply for fun. Our version is one that Sam Larner learnt while working in the Lowestoft drifter fleet.

Bold Riley O: Shellbacks manning the windjammers of the West Indies trade brought back to Liverpool and Bristol more than sugar, bananas and rum; they also brought back many songs. Some of these they kept to themselves, some they handed on to vessels sailing in other waters. Thus the fine hexatonic tune of Bold Riley O, which started life as a Tobago reel, was sung at the halyards of many an East Indiaman bound for Bombay and the Bengal ports.

Haul away for Rosie: A tack and sheet shanty, some' times known as Haul away, Joe. It has many tunes, but none better than this swingy Mixolydian one. Stan Hugill reports that, a generation ago, Liverpool children were using a variant of the disorderly final verses of this shanty as a skipping rhyme. Songs of innocence …

Nancy of Yarmouth: To dress in sailor's clothes and smuggle oneself aboard ship was a pretty notion that often occurred to young girls a century or two ago, if the folk songs are to be believed. This song has been widely found in the south of England, also in Ireland. It seems to belong to an age when seamen had more delicate minds than they were later to display.

Tom's Gone to Hilo: Tom left home on a ship bound for the nitrate port of Ilo, Peru. The Liverpool judies had treated him roughly, while the Valparaiso girls were kind, and it looked as if Tom wasn't going to return. His defection seemed to strike a mood of tender sentiment in the teak-tough hearts of seamen, for though this tops'l halyard shanty has several tunes, they are all of melting nostalgic character. Perhaps the men on the rope wished they were in Tom's shoes. The slow tempo of Tom's Gone suited the crew when the pull was heavy, but it was no favourite with the officers, who liked to hear the shanties going brisker.

Sally Brown: Sally Brown is one of those mythological figures that recur over and again in the shanties. Others of the same company are Stormalong, Ranzo, and (perhaps a brother to Sally?) Shallow Brown. Usually, Sally is described as a mulatto girl of great beauty and impressive proportions, and it seems that the goddess of love was not more highly thought of in classical times, than Sally Brown in the foc'sles of windjammers in the 19th century. The singular tune, with its fluctuating thirds and sevenths, interested Cecil Sharp when he heard it sung in the Marylebone Workhouse, London, by old Charlie Robbins, an ex-seaman down on his luck.

The Dockyard Gate: Womenfolk in sailors' songs are usually either innocent girls with cherry cheek and shining eye, or they are striding women of the town, with feathered hats and nimble fingers. More rarely, the men sang of the hard-case wives who spend their husband's allotment in entertaining their lovers and who, as the money runs short, utter the cheering cry of: "Never mind, my love, he's working hard for more!" Such is the situation in this song which Ewan MacColl recorded from Sam Larner. Miss Gilchrist obtained a set of it from old Mr. Bolton, and Frank Kidson heard it sung by a sailor's daughter in Yorkshire.

Hilo Somebody: Another of the extensive "Hilo" family of shanties heard by R. R. Terry on Tyneside. It makes fetching use of the ancient folkloristic device of the talking bird. Alabama cotton hoosiers knew this shanty, but it is not clear whether they learned it from sailors or the sailors learned it from them. Stan Hugill prints a version obtained from a Tobago seaman, with a tune very close to Terry's.

The "Dolphin": The Dolphin, out of Liverpool, is accosted by a pirate ship off the African coast and she shows the enemy her teeth. More usually, the song concerns the London man-o'-war sailing from Plymouth or Spithead, who meets a French navy vessel off the shores of Ireland, cripples her, and tows her home as a prize. As such, the song is known as The "London" or The Irish Captain. It probably dates from the Napoleonic wars. Ewan MacColl recorded the present version from Sam Larner, who learnt it from a fellow fisherman, "dead fifty year now", called Old Larpin.

The Trim-Rig Ducksie: This wry and saucy is also known as The Rambling Sailor. In fact it began life as The Rambling Soldier, and as such was a favourite song with fairground singers in the 18th century. In 1818, perhaps capitalizing on the wave of popularity enjoyed by British tars in the years following Trafalgar, the ballad-sheet printer John Catnach (father of the more famous Jemmy) published an altered version of the song, with the saucy soldier now become a sailor. The song's unbuttoned text seems to have worried the folk song collectors. The Rev. Baring Gould, H.E.D. Hammond and Cecil Sharp all obtained several versions of it, but found its wit and point "not very choice", and suppressed most of the text as unfit for polite ears. Less polite country singers remain devoted to the song, whose swinging mixolidian melody is also that of a West Country hornpipe.

Little Sally Racket: A halyard shanty, sometimes called Cheer'ly Men (meaning "Quickly, men"). One of the liveliest of shanties in tune, one of the roughest in text. Some versions of it are among the oldest of familiar British shanties, though 19th century writers reported that it was frowned on in Yankee ships (yet Dana heard it aboard the Pilgrim in the 1830s). Our version was common in the West Indies run, and seems to derive from a melody known in Jamaica as Mr. Ramgoat or Hill and Gully.

Gal with the Blue Dress on: A halyard shanty, most shellbacks say, though at least one 19th century collection names it as a pumping song. Known to Liverpool seamen, but sounding much like a Negro composition. Perhaps the stanza that says: "She's a Windward gal with a Windward smile, At a dollar a time it's well worth while" is a clue pointing to the West Indies for the song's origin. Some versions of the well-known Whisky Johnny are related, in tune, to the Blue Dress shanty.

The Leaving of Liverpool: W. Doerflinger got this nostalgic song from a well-known shanty singer, "Cap' tain" Dick Maitland, who learnt it from a Liverpool man when he was bosun of the General Knox about 1885. It seemed to have disappeared from its own home town, but since Doerflinger printed it, it has taken a new lease of life, and is now not infrequently heard in the city folk song clubs.

Bring 'em Down: Like Bold Riley O, this tune (a Dorian one) was brought to Liverpool from the West Indies where a variant of it had served as a challenging stick-fight song. Among the vessels that adopted the tune as a shanty for heavy hauling were those running up the coast of Chile. Oldtime sailors, who had a high regard for Valparaiso women, pronounced the name of the country to rhyme with "versatile".

Hilo John Brown: Many shanties sing of Hilo. Some say it means the sailor-town on the eastern side of Hawaii Island; some say it refers to the dusty nitrate port of Ilo, Peru; others say that, as often as not, it just means "Hullo" or even "Haul-o". R. R. Terry heard this halyard shanty sung by Tyneside seamen, but it surely owes its origin to sunnier, southerly climates.

Short Jacket and White Trousers: Girls dressed in male attire, living "man to man" in the foc'sle with rough seamen, may find themselves in delicate situations. This song offers an unusually quizzical but characteristically goodnatured view of the matter. The song is still known among British seamen in various stages of dilapidation and differing degrees of coarseness. For some reason it has seldom found its way into print. Greenleaf and Mansfield found a good version in Newfoundland, and we've borrowed some of their delicate lines to replace a few rough passages in the song as sung by ex-bosun Ned Close of London.

The Blackball Line: First and most famous of the packets running across the Western Ocean to Liverpool were the little ships of the Black Ball line. Their crimson swallowtail flag with a black ball in the centre was an emblem of hardship for seamen. The voyage-schedules were tight, discipline was unmerciful, and for cheapness — so the songs say — "tinkers and tailors, shoemakers, and all, are all shipped as sailors aboard a Black Ball". Nevertheless, Black Ball seaman had their special pride, as this capstan shanty with its bold "hooraw chorus" well illustrates.

General Taylor: The Mexican War threw up some good shanties. British seamen, many of whom jumped ship to fight on the Mexican side, sometimes sang as if General Santa Ana had been victorious at the decisive battle of Molina del Rey. The present shanty restores history to a truer perspective, for surely enough, "General Taylor gained the day". Yet still there is confusion, for somehow Taylor's figure has merged with that of the legendary Stormalong, and the general is given the ceremonial funeral that is usually accorded to old Stormy. Cecil Sharp noted this intricate tune with its melismatic "hitches" from a shantyman named Short, of Watchet in Somerset.

Notes by A. L. Lloyd