|

|

Sleeve Notes

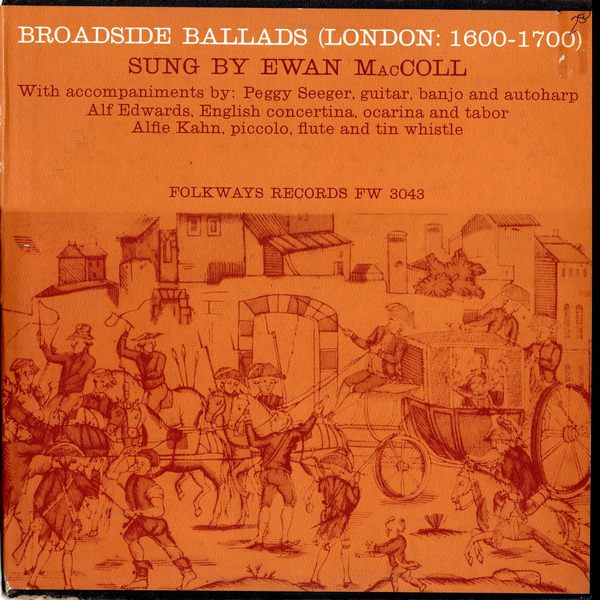

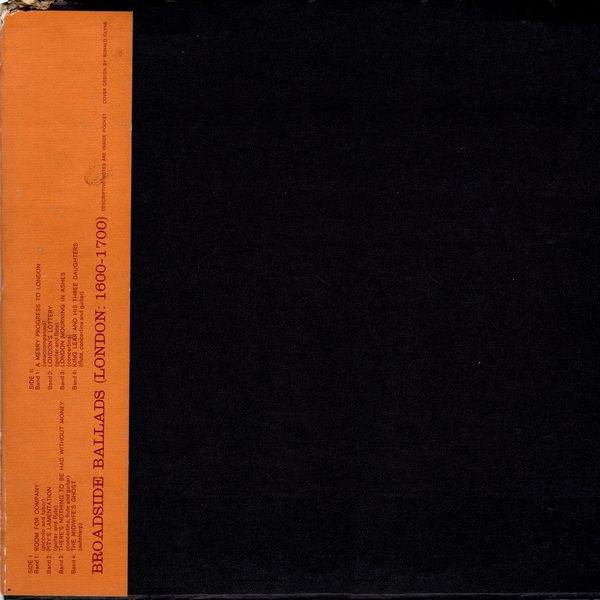

BROADSIDE BALLADS

The term 'Broadside Ballad' is here used to designate any song — narrative or otherwise — which made its first appearance on the penny or halfpenny sheets.

The songs which make up these two albums do not, for the most part, have much in common with the Traditional Ballads.

Professor Child has characterized the broadsides as "veritable dunghills", and for three hundred years contemptuous literary men have castigated the authors of these 'vile ballads'; and yet even the most awkward of their verses has its occasional flash of humour, its sudden, brief flicker of light, making the dead past live again for a moment. If our view of the past, occasioned by these momentary illuminations, is sometimes an oblique one, then it is none the less interesting on that account.

The broadsides flourished from 1500-1700, that is until the first cheap books began to make their appearance. By the beginning of the 18th century, the black-letter ballads had virtually disappeared.

The White-letter productions, however, persisted until the mid-nineteenth century, and indeed, even today it is not unusual for one to be accosted in the London streets by a 'soft touch man' who in return for a shilling will slip you an envelope containing a miniature photostat copy of a ballad dealing with the 'Loss of the Royal Sovereign' in World War II, or with the 'Sinking of the Scharnhorst'.

In the days before TV, radio and newspapers, the broadsides helped both to mould and reflect public opinion; their authors acted as political commentators, journalists, comic-strip writers, P. R. men for both parties, and for all those ambitious placeseekers who could afford to hire a pen.

That they were popular with the masses, no one can doubt; that they were unpopular with the establishment is born out by successive acts of legislation against 'pipers, fiddlers and minstrels' and by the many repressive laws directed against them both in England and Scotland.

In 1574 (in Scotland) they were again branded with the oprobrious title of vagabonds and threatened with severe penalties; and the regent Morton induced the Privy Council to issue an edict that "nane tak upon hand to emprint or sell whatsoever book, ballet, or other werk" without its being examined and licenced under pain of death and confiscation of goods.

In August 1579, two poets of Edinburgh, (William Turnbull, Schoolmaster and William Scot, notar, "baith weel belovit of the common people for their common offices") were hanged for writing a satirical ballad against the Earl of Morton, and in October of the same year, the Estates passed an act against beggars and "sic as make themselves fules and are bards ... minstrels, sangsters, and tale-tellers, not avowed in special service by some of the lords of parliament or great burghs."

Seventy-five years later, Captain Bentham was appointed provost-marshall to the revolutionary army in England, with power to seize upon all balladsingers, and five years after that date there were no more entries of ballads at Stationers' Hall. The heat was still on a century later and in July 1763, we are told that "yesterday evening two women were sent to Bridewell by Lord Bute's order, for singing political ballads before his lordship's door in South Audley Street".

Even in the mid-nineteenth century the attacks on the ballad-mongers continued, though by this time the fraternity was somewhat reduced in size; yet it was still sufficiently large for the owners of factories and workshops like the Vulcan foundry of Newton-Le-Willows, Cheshire to deem it necessary to issue the following warning on a cast-iron notice board: TAKE NOTICE. PRIVATE PROPERTY.

We do hereby caution all HAWKERS, RAG AND BONE DEALERS, BALLAD SINGERS & From trespassing on these premises. Any person or persons of the above description found hereon after this notice will be prosecuted with the utmost rigor of the LAW. VULCAN FOUNDRY MAY 1st. 1835.

They have departed now; it is no longer necessary for the authorities to brand "bardis and balletsingers" on the cheek and scourge them through the streets. The descendents of Elderton, Deloney, Johnson, Munday and Martin Parker now work for the establishment, as the hired men of television, radio, the press and Tin Pan Alley; they have learned how to write without offending anybody or anything, except, occasionally, one's sense of the ridiculous.

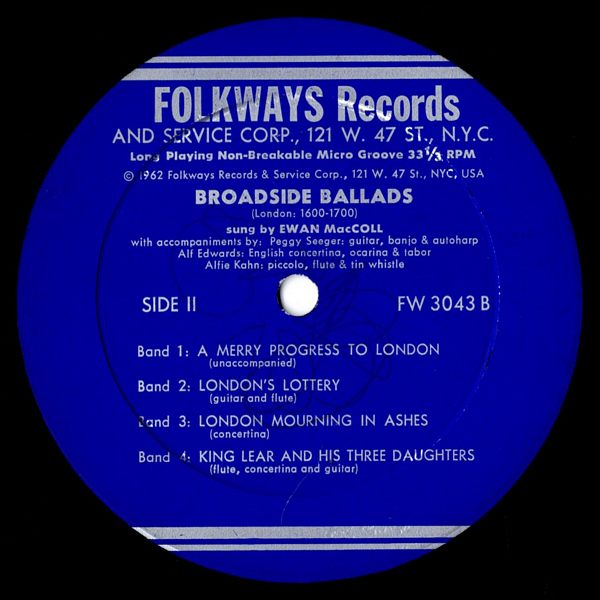

The Accompaniments

The broadsides were, for the most part, sung on the streets and in the taverns of Britain's cities. If they had accompaniments at all, these would probably have been of a most rudimentary nature. To have presented them in these albums with the sophisticated virginals and lute would have been as incongruous as arranging the St. Louis Blues for the serpent and three Alpine horns. It is much more likely that instruments such as the pipe and tabor and fiddle were used. For this present recording we have made no attempt to provide "authentic" accompaniment. We have used instead the concertina, the guitar, the ocarina, flute, piccolo, tin whistle, autoharp, tabor and, for two songs, the banjo; all of them instruments which have been widely used by street singers of our own time.

Notes by EWAN MacCOLL

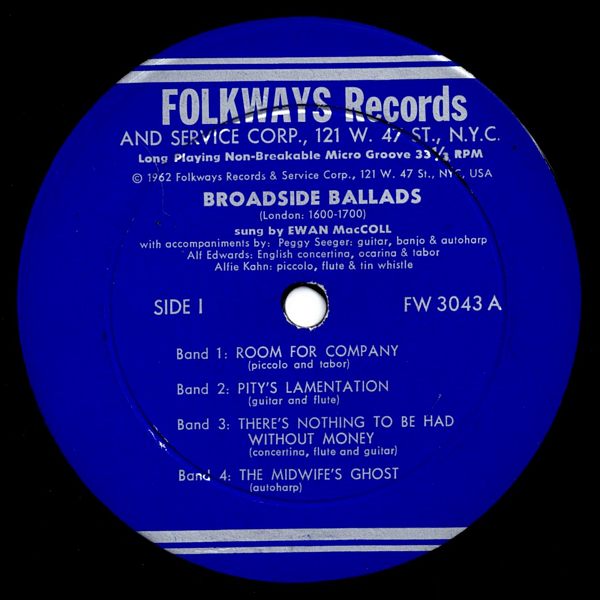

Room for Company — The ballad was registered by John Trundle under the title of "Rome for Company in Bartholomew Faire" on October 22, 1614, the year in which Ben Jonson's hilarious play, "Bartholomew Fair", was first presented to London theatre-goers. The earliest printed version of the melody is in Playford's "Musick's Recreation on the LYRA VIOL" (1652).

Imprinted at London for E. W.

Seven of the twenty-one verses are given here.

Source: The Pepys Ballads

Pity 'S Lamentation — Rollins places the date of composition of this ballad as 1615-16 and surmises that the fourth stanza refers to the murder of Sir Thomas Overbury (1613). The rising cost of living brought about by economic changes in the reign of James the First inspired a number of ballads lamenting the passing of "the good old days". The most notable of these pieces was Martin Parker's well-known ballad 'Time's Alteration. ' The tune is "Packington's Pound" and is to be found in Queen Elizabeth's VIRGINAL BOOK. Seven of the fifteen verses are given here.

Printed at London for I.W.

Source: The Pepys Ballads

There's Nothing to Be Had Without Money — The tune, known as "Stingo" and as "Oil of Barley" has been used for a large variety of ballads, most of which have for their theme the value of money. Nine of the fifteen stanzas are given here.

Printed at London for H(enry) G(osson).

Source: Evans Old Ballads

The Midwife's Ghost — Probable date of composition, 1680. The events described in the ballad are more fully reported in Nathaniel Thompson's newspaper 'The True Domestick Intelligence, or News Both from City and Country', No. 74 March 16-19, 1780. The tune is "Queen Dido", or "Troy Town". A ballad entitled 'The Wanderynge Prince (of Troy) 'was entered on the Registers of the Stationers' Company in 1564-5. Eight of the fifteen stanzas are given here.

London, Printed for T. Vere at the sign of the Angel in Guiltspur Street.

Source: The Pepys Ballads

Who appeared to several People in the House where she formerly lived in Rotten-Row in Holbourn, London, who were all afraid to speak unto her; but she growing very Impetuous, on the 16th of this Instant March, 1680, declared her mind to the Maid of the said House, who with an Unanimous Spirit adhered to her, and afterwards told it to her Mistris, how that if they took up two Tiles by the Fire-side, they should find the Bones of Bastard-Children that the said Midwife had 15 years ago Murthered, and that she desired that her Kins-woman Mary should see them decently Buried; which accordingly they did and found it as the Maid had said. The Bones are to be seen at the Cheshire-Cheese in the said place at this very time, for the satisfaction of those that believes not this Relation.

A Merry Progress to London — Rollins places the date of composition about 1620.

The theme of the country squireen being gulled in the big brutal city was a favourite one both with 17th century ballad writers and with their more respectable brothers, the dramatists. In the comedies of Ben Jonson, the theme recurs constantly, generally accompanied by the tobacco symbol. Tobacco was introduced into England by Ralph Lane, the first governor of Virginia, and made fashionable by Sir Walter Raleigh. The tune, 'Riding to Romford', is given in Chappell's POPULAR MUSIC OF THE OLDEN TIME under the title of "Cupid's Courtesy."

Ten of the eighteen stanzas are given here.

Imprinted at London for I. White.

Source: The Pepys Ballads

London's Lottery — The novel method of raising money mentioned in this ballad had for its objective the establishment of a colony in Virginia. The winner of the first prize in the lottery was one Thomas Sharplisse, a London tailor. "Foure thousande crownes in fayre plate, was sent to his house in very stately manner".

"Henry Roberts registered 'London's Lottery1 on July 30, 1612 — a date, curiously enough, ten days after the lottery had ended. " (Rollins).

Imprinted at London by W. W. for Henry Robards, and are to be sold at his shop neere to S. Botulphes Church without Aldergate, 1612.

The Pepys broadside directs that the ballad be sung to the tune of "The Lusty Gallant". Six of the twenty-one verses are given here.

London Mourning in Ashes — Two-thirds of the City of London was destroyed by 'the great fire' of 1666. The Dutch, the French and the Catholics were all, in their turn, accused of being the incendiaries, while the more sober citizens inclined to the view that the fire was assigned from the Almighty, that worse was yet to come unless the populace abandoned its sinful ways. The melody is contained in a manuscript volume of virginal music, transcribed by Sir John Hawkins, where it has the title of "In Sad and Ashy Weeds". Seven of the sixteen stanzas are given here.

London, Printed for E. Crowch, for F. Coles, T. Vere and J. Wright.

Lamentable Narrative lively expressing the Ruine of that Royal City by fire which began in Pudding-lane on September the second, 1666, at one of the clock in the morning being Sunday, and continuing until Thursday night following, being the sixth day, with the great care the King, and the Duke of York took in their own Persons, day and night to quench it.

King Lear And His Three Daughters — The first 4th edition of Shakespeare's play is dated 1608. That the theme was a popular one is borne out by the fact that a play dealing with King Lear was entered in the Stationers' Register as early as 1594. The tune 'Flying Fame' has had a large number of texts written to it. Fifteen of the twenty-three stanzas are given here.

From an ancient copy in "The Golden Garland", bl, let, intitled 'A Lamentable Song of the Death of King Leir and his Three Daughters'.

Source: Percy's Reliques

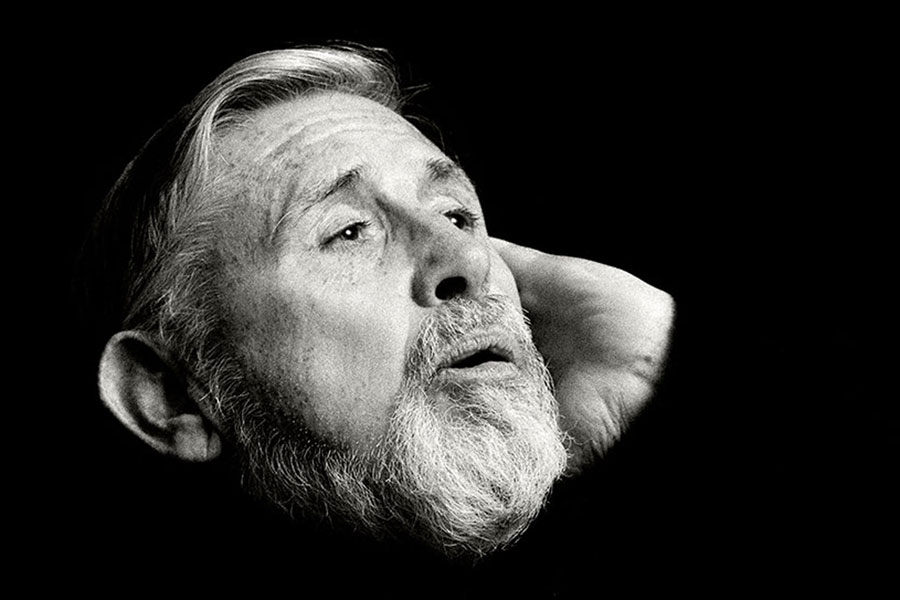

EWAN MacCOLL

Ewan MacColl is that rare combination of traditional and revival singer at one and the same time. Born in Auchterarder, Perthshire, Scotland on January 25, 1915 (on Bobby Burns' birthday), MacColl learned most of his songs from his father and other members of his family, as well as from Scottish and English neighbors of childhood days. "My old man was the best singer I ever heard," he says. Unlike so many traditional singers whose music was kept alive in relatively isolated rural areas, the MacColl family was a product of the industrial age. His father was an iron-moulder who worked at his trade irregularly as a result of being blacklisted for trade union organizing activities. His mother, from whom he also learned many songs worked on and off as a charwoman in all the industrial cities of England and Scotland as the MacColls moved from town to town trying to escape the penalties of the father's trade union activities. One writer has called him the "Folksinger of the Industrial Age" During the 1930's, MacColl found himself in the burgeoning British workers' theater movement. His natural political inclinations, together with an instinctive flair for drama and song led him to the "agitprop" performing groups of the depression era whose stage was more often a street before a factory gate or a union meeting hall than a formal theater. In the years since then, he has become the leading presenter of folk songs on British radio and television, either writing or appearing in more than 50 different BBC programs. Song-writer, recording and concert artist (he has toured throughout Europe and Canada), Ewan MacColl is a towering figure in the world of folk music.