|

|

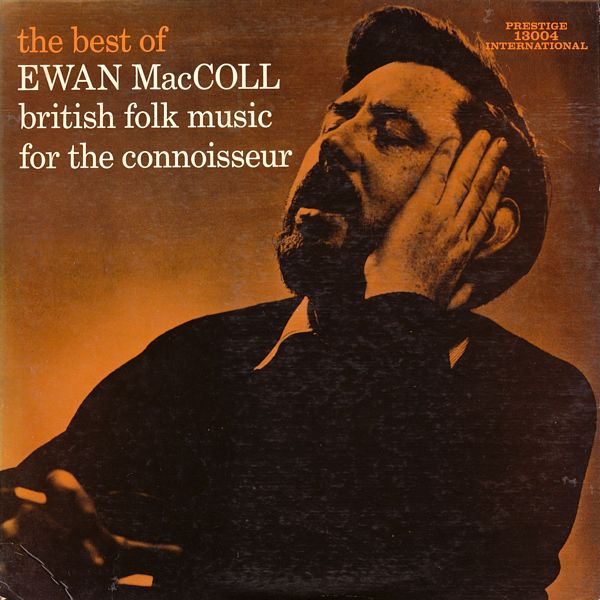

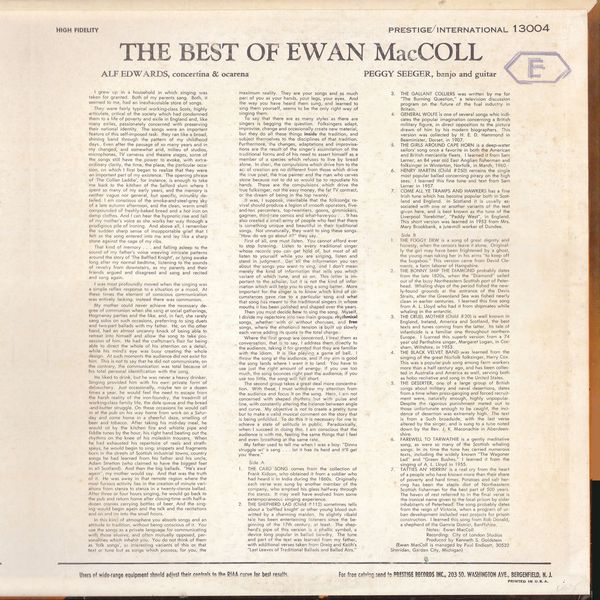

Sleeve Notes

I grew up in a household in which singing, was taken for granted. Both of my parents sang. Both, it seemed to me, had an inexhaustable store of songs.

They were fairly typical working-class Scots, highly articulate, critical of the society which had condemned them to a life of poverty and exile in England and, like many exiles, passionately concerned with preserving their national identity. The songs were an important feature of this self-imposed task: they ran like a broad, shining band through the pattern of my childhood days. Even after the passage of so many years and in my changed, and somewhat arid, milieu of studios, microphones, TV cameras and theatre stages, some of the songs still have the power to evoke, with extraordinary clarity, the time, the place, the particular occasion, on which I first began to realize that they were an important part of my existence. The opening phrase of 'The Collier Laddie', for instance, is enough to take me back to the kitchen of the Salford slum where I spent so many of my early years, and the memory is neither vague nor general, but specific, minutely detailed. I am conscious of the smoke-and-steel-grey sky of a late autumn afternoon, and the clean, warm smell compounded of freshly-baked bread and a hot iron on damp clothes. And I can hear the hypnotic rise and fall of my mother's voice as she works her way through a prodigious pile of ironing. And above all, I remember the sudden sharp sense of insupportable grief that I felt as the song entered into me and lay like a sharp stone against the cage of my ribs.

That kind of memory … and falling asleep to the sound of my father's voice weaving intricate patterns around the story of 'The Baffled Knight', or lying awake long after my normal bedtime, listening to the sounds of revelry from downstairs, as my parents and their friends argued and disagreed and sang and recited and sang again.

I was most profoundly moved when the singing was a simple reflex response to a situation or a mood. At these times the element of conscious communication was entirely lacking: instead there was communion.

My mother could never achieve the necessary degree of communion when she sang at social gatherings, Hogmanay parties and the like, and, in fact, she rarely sang solos on such occasions, preferring to sing duets and two-part ballads with my father. He, on the other hand, had an almost uncanny knack of being able to retreat into himself and allow the song to take possession of him. He had the craftsman's flair for being able to direct the whole of his attention on a detail, while his mind's eye was busy creating the whole design. At such moments the audience did not exist for him. This is not to say that he did not communicate; on the contrary, the communication was total because of his total personal identification with the song.

He liked to drink, but he was never a heavy drinker. Singing provided him with his own private form of debauchery. Just occasionally, maybe ten or a dozen times a year, he would feel the need to escape from the harsh reality of the iron-foundry, the treadmill of working-class family life, the dole queue and the bread -and-butter struggle. On these occasions he would call in at the pub on his way home from work on a Saturday and come home in a cheerful daze, smelling of beer and tobacco. After taking his mid-day meal, he would sit by the kitchen fire and whistle pipe and fiddle tunes by the hour, his right hand beating out the rhythms on the knee of his moleskin trousers. When he had exhausted his repertoire of reels and strathspeys, he would begin to sing: snippets and fragments born in the streets of Scottish industrial towns, country songs he had learned from his father and his uncle, Adam Stretton (who claimed to have the biggest feet in all Scotland). And then the big ballads. "He's awa' again", my mother would say. And that was the truth of if. He was away in that remote region where the most furious activity lies in the creation of minute variations from stanza to stanza in a twenty-stanza ballad. After three or four hours singing, he would go back to the pub and return home after closing-time with half-a-dozen cronies carrying bottles of beer. And the singing would begin again and the talk and the recitations and on and on into the small hours.

In this kind of atmosphere you absorb songs and an attitude to tradition, without being conscious of it. You use the songs as a private language for communicating with those elusive, and often mutually opposed, personalities which inhabit you. You do not think of them as 'folk songs', as interesting variants of this or that text or tune but as songs which possess, for you, the maximum reality. They are your songs and as much part of you as your hands, your legs, your eyes. And the way you have heard them sung, and learned to sing them yourself, seems to be the only right way of singing them.

To say that there are as many styles as there are singers is begging the question. Folksingers adapt, improvise, change and occasionally create new material, but they do all these things inside the tradition, and subject themselves to the disciplines of that tradition. Furthermore, the changes, adaptations and improvisations are the result of the singer's assimilation of the traditional forms and of his need to assert himself as a member of a species which refuses to live by bread alone. In short, the compulsions which drive him to the act of creation are no different from those which drive the true poet, the true painter and the man who carves stone because not to do so would be to repudiate his hands. These are the compulsions which drive the true folksinger, not the easy money, the fat TV contract, or the dream of being in the top twenty.

It was, I suppose, inevitable that the folksongs revival should produce a legion of smooth operators, five-and-ten percenters, top-twentiers, goons, gimmickers, gagmen, third-rate comics and what-have-you … It has also created a small army of people who feel that there is something unique and beautiful in their traditional songs. Not unnaturally, they want to sing these songs. "How do we go about it?" they say.

First of all, one must listen. You cannot afford ever to stop listening. Listen to every traditional singer whose records you can get hold of, but most of all listen to yourself while you are singing, listen and stand in judgment. Get all the information you can about the songs you want to sing, and I don't mean merely the kind of information that tells you which variant of which tune, and so on. This latter is important to the scholar, but it is not the kind of information which will help you to sing a song better. More important for the singer is to know which kind of circumstances gave rise to a particular song and what that song has meant to the traditional singers in whose mouths it has been polished and shaped over the years.

Then you must decide how to sing the song. Myself, I divide my repertoire into two main groups: rhythmical songs, whether with or without choruses, and free songs, where the emotional tension is built up slowly each verse adding its quota to the total charge.

Where the first group are concerned, I treat them as conversation, that is to say, I address them directly to the audience, taking it for granted that they are familiar with the idiom. It is like playing a game of ball. I throw the song at the audience, and if my aim is good the song lands where I want it to land. You have to use just the right amount of energy: if you use too much, the song bounces right past the audience; if you use too little, the song will fall short.

The second group takes a great deal more concentration. With these, I must withdraw my attention from the audience and focus it on the song. Hers, I am not concerned with shaped rhythms but with pulse and line, with constantly altering the balance between angle and curve. My objective is not to create a pretty tune but to make a valid musical comment on the story that is being unfolded. To do this it is necessary for me to achieve a state of solitude in public. Paradoxically, when I succeed in doing this. I am conscious that the audience is with me, feeling the same things that I feel and even breathing at the same rate.

My father used to tell me when I was a boy: "Dinna struggle wi' a sang … let it hae its heid and it'll get you there."

THE CARD SONG comes from the collection of Frank Kidson, who obtained it from a soldier who had heard if in India during the 1860s. Originally each verse was sung by another member of the company, who emptied his glass halfway through the stanza. It may well have evolved from some extemporaneous singing experience.

THE SHEPHERD LAD (Child #112) sometimes tells about a 'baffled knight' or other young blood outwitted by a charming maiden. Its slightly ribald tale has been entertaining listeners since the beginning of the 17th century, at least. The shepherd's pipe of this version is a phallic symbol, a device long popular in ballad bawdry. The tune and part of the text was learned from my father, with additional verses taken from Greig and Keith's "Last Leaves of Traditional Ballads and Ballad Airs."

THE GALLANT COLLIERS was written by me for "The Burning Question," a television discussion program on the future of the fuel industry in Britain.

GENERAL WOLFE is one of several songs which indicates the popular imagination concerning a British military figure, in direct opposition to the picture drawn of him by his modern biographers. This version was collected by H. E. D. Hammond in Beaminister, Dorset, in 1907.

THE GIRLS AROUND CAPE HORN is a deep-water sailors' song once a favorite in both the American and British mercantile fleets. I learned it from Sam Larner, an 84 year old East Anglian fisherman and folksinger in Winterton, Norfolk, in March, 1960.

HENRY MARTIN (Child #250) remains the single most popular ballad concerning piracy on the high seas. I learned this fine tune and text from Sam Larner in 1957.

COME ALL YE TRAMPS AND HAWKERS has a fine Irish tune which has become popular both in Scotland and England, in Scotland it is usually associated with one or another variants of the text given here, and is best known as the tune of the Liverpool 'forebirter', "Paddy West", in England. This short version was learned in 1953 from Mrs. Mary Brookbank, a jute-mill worker of Dundee.

THE FOGGY DEW is a song of great dignity and honesty, when the censors leave it alone. Originally the girl may have been frightened by a ghost, the young man taking her in his arms "to keep off the bugaboo." This version came from David Clements, a farm laborer of Hampshire.

THE BONNY SHIP THE DIAMOND probably dates from the late 1820s, when the "Diamond" sailed out of the busy Northeastern Scottish port of Peter-head. Whaling ships of the period fished the newly-found grounds at the entrance of the Davis Straits, after the Greenland Sea was fished nearly clean in earlier centuries. I learned this fine song from A. L. Lloyd who had it from shipmates while whaling in the antarctic.

THE CRUEL MOTHER (Child #20) is well known in England, Ireland, America and Scotland, the best texts and tunes coming from the latter. Its tale of infanticide is a familiar one throughout northern Europe. I learned this superb version from a 74 year old Perthshire singer, Margaret Logan, in Cor-sham, Wiltshire, in 1953.

THE BLACK VELVET BAND was learned from the singing of the great Norfolk folksinger, Harry Cox. This was a popular pub song among farm workers more than a half century ago, and has been collected in Australia and America as well, serving both as hobo recitative and song in the United States.

THE DESERTER, one of a large group of British songs about military and naval desertions, dates from a time when press-ganging and forced recruitment were, naturally enough, highly unpopular. Despite the rigorous punishment meted out to those unfortunate enough to be caught, the incidence of desertion was extremely high. The text is from a Such broadside, with the last verse altered by the singer, and is sung to a tune noted down by the Rev. J. K. Maconachie in Aberdeen-shire.

FAREWELL TO TARWATHIE is a gently meditative song, as were so many of the Scottish whaling songs. In its time the tune has carried numerous texts, including the widely known "The Wagoner Lad" and "Green Bushes." I learned it from the singing of A. L. Lloyd in 1955.

TATTIES AN' HERRIN' is a real cry from the heart of a people who have known more than their share of poverty and hard times. Potatoes and salt herring has been the staple diet of Northeastern Scottish fisherman for the best part of 500 years. The haven of rest referred to in the final verse is the ironical name given to the local prison by older inhabitants of Peterhead. The song probably dates from the reign of Victoria, when a program of urban development included vast projects for prison construction. I learned this song from Rob Donald, a shepherd of the Gamrie District, Banffshire.