Sleeve Notes

Introduction

In Northeast Scotland it was the practice, until fairly recent times, for male farmworkers to be accommodated in buildings separate from the farm house proper. Such buildings were known as bothies.

Ploughmen and other farm servants sold their services to a farmer on a seasonal basis, the transaction generally being arranged at a seasonal "feeing market", or hiring fair.

In the days before radio, television and cheap transport brought urban civilisation into every farm kitchen farm servants had, of necessity to provide their own forms pf amusement and expression. Since £he area where such conditions prevailed was one which was extremely rich in traditional songs and ballads, it was natural that the bothies should continue the tradition of song and music-making.

The gradual mechanisation of agricultural processes which began in the mid-19th century did, of course, tend to limit the thematic area of the bothy songs. The introduction, for example, of the reaping machine and the mechanical shearer made sharing and harvest songs things of the past, while the Education Act of 1872 practically abolished herding, which until this time had been largely a children's occupation. The end of the herding practice meant that no new herding songs were created and that those already in existence tended to be forgotten.

The mechanisation of ploughing, however, was a much more gradual development than, say, the mechanisation of harvesting tools for, by the end of the 19th-century almost all the large farms of Northeast Scotland were equipped with reaping machines and mechanical binders. It is true that after i860 the plough horse was, in some places, replaced by the steam tractor and after 1900 the motor tractor made its appearance — but the change was gradual. Horses were not only an important factor in farming economy but, in addition, the possession of a good team of plough horses conferred a great deal of social prestige on their owner. The men who drove, fed and looked after the horses, that is, the ploughmen, were considered to be the aristocrats of the Scots agricultural scene and there was a good deal of competitive striving amongst them when it came to exhibiting prowess and skill with a plough and a team.

Something of the nature of a primitive secret society of ploughmen had been in existence from at least the third quarter of the 18th-century and with initiation ceremonies, passwords and special handclasps the society played an important part in controlling entry into the craft and in maintaining a high level of skill.

The period which followed the first World War saw the mechanisation of agriculture tremendously accelerated and by the 30's there were only a handful of farms where the bothy system still operated. The second World War completed the process and today the ploughmen's "grip and word" are things of the past. The horses have been superseded by the tractor and the ploughmen by the mechanic.

The only real record we have of this ancient craft is the bothy songs for in them the ploughman reigns as undisputed hero. In the introduction to Bothy Songs and Ballads of Aberdeen, Banff and Moray Angus and the Mearns, John Qrd writes: "Bothy song is just another name for folksong." This is altogether too wide a definition. That they are folksongs is true, but they are folksongs which have originated in the bothies and which deal exclusively with the lives and experiences of those farm servants, particularly the ploughmen, who were part of the bothy system. They are a special group of folksongs in the way the sea shanties and forebitters are a special group.

A great many other types of songs were sung in the bothies and farm kitchens; traditional ballads, whaling songs, broadsides and old country songs, but these are, so to speak, bothy songs by adoption. In the mouths of bothy singers they were often transformed and invested with the stylistic characteristics of the true bothy song.

If the hero of the bothy ballads is the ploughman then the villian is the farmer who employs him, or the foreman who carries out the farmers instructions. It is the farmer who pays poor wages and provides the ploughman with a monotonous diet, it is the farmer (or the foreman) who drives him to work outdoors in all kinds of weather, it is the farmer who is responsible for all the discomforts which the ploughman suffers in the course of his work. It is the farmer, or the farmer's wife who prevents free intercourse between men and women farm servants and, because he considers the ploughman to be his inferior, prohibits social contact between ploughmen and members of his own family. Finally, and this is the worst crime of all, it is the farmer who starves the plough horses and thus strikes directly at the ploughman's professional status.

In spite of all this, however, the bothy ballads cannot be described as "protest songs". They reflect a social attitude but it is an apolitical one. The ploughman may complain about poor food and sick horses but he accepts these things as hit lot. When he is cheated out of his wages or his economic rights are attacked, he does not strike or resort to political action, he merely waits for his feeing term to expire and finds a new employer. Again, when thwarted in the pursuit of sexual fulfilment he does not insist on his human rights, but resorts to stratagems.

He does, however, manage to revenge himself upon his employer by caricaturing him and exposing his faults, by cuckolding him and by stealing his daughter's affections. These victories are, for the most part, possible only in the fantasy world of the songs.

The preoccupation with traditional balladry has created its own form of snobbery. Collectors of folk-songs and folk song anthologists have tended to be rather patronizing about the bothy songs. In fact, our native collectors have, on the whole, treated them with the same disdain with which American folklorists and musicologists have treated hillbilly music.

And yet, the fact remains that, along with the sea shanties, the bothy ballads constitute the most important body of folksongs to be created in the 19th-century.

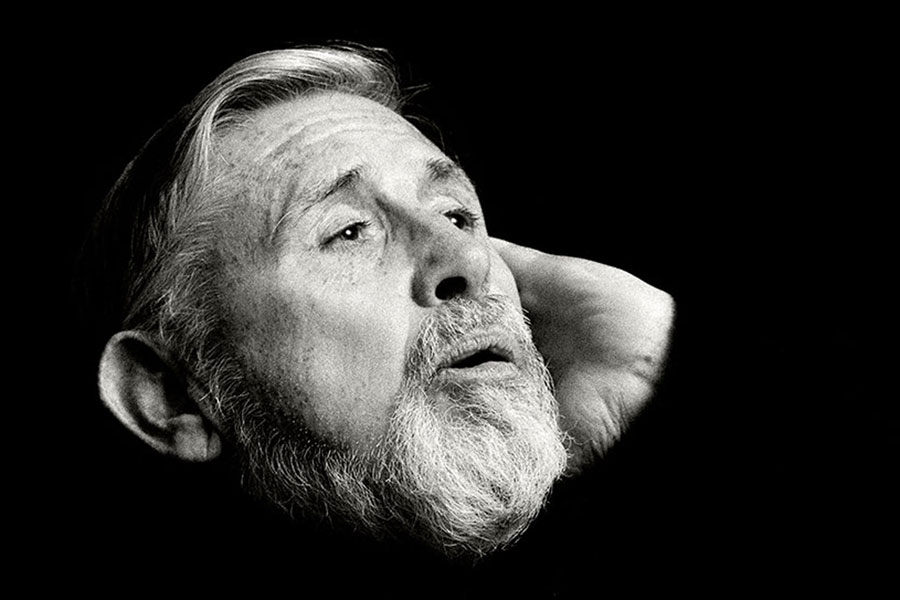

— Ewan MacColl

The Keach In the Creel — (Child 281) The first printed version of this ballad did not appear until early in the nineteenth century although the theme has been part of European literature since the middle ages. Professor Child concludes his notes on the ballad with a peculiarly prim comment: "No one looks for decorum in pieces of this description but a passage in this ballad, which need not be particularized, is brutal and shameless almost beyond description."

These are harsh words for a scholar whose stock-in-trade was stories dealing with mayhem in all its forms and it is difficult to imagine what prompted them. It is, of course, possible that Child was shocked by the use of the word 'keach' on which considerable play is made in the song. Used as a noun the word denotes bustle or fluster, when used as a verb, however, it can mean 'lift' or 'hoist' or alternatively it can mean to void excrement. The ballad is widespread throughout N.E. Scotland and was a favourite in the bothies where it was generally known as The Wee Toon Clerk.

Learned from the singing of Jimmy MacBeth of Elgin.

I'm A Rover — This night-visit song is almost certainly related to The Grey Cock (The Lover's Ghost), a ballad in which a girl is visited by the ghost of her dead lover. As A. L. Lloyd has observed: "Generally the song is found either with the bedroom-window theme or the cockcrow theme but not the two together. In this version the bedroom-window theme is clearly established and what Remains of the cock-crow theme has lost its supernatural significance.

From the singing of James Grant of Aberdour, Banffshire.

The Scranky Black Farmer — Until recently it was common for East-Anglian countrymen to spend part of the year working on the land and part working on the sea as herring-fishermen. In N. E. Scotland, however, this was never the practice, the two communities always being sharply divided. Consequently, it is unusual to find in the bothy singer's repertoire a song in which the seaman's attitude to farm-work is expressed.

From the singing of James Grant of Aberdour, Banffshire.

The Band of Shearers — This song was the work of Robert Hogg (a nephew of James Hogg, the Ettrick Shepherd) who was born at Stobo in Peebles, in 1799. In Ord's introduction to Bothy Songs and Ballads there is an interesting note concerning shearers: "The shearing was mostly done by women. The value of a day's work was calculated by the number of thraives cut. A thraive consisted of two stooks of twelve sheaves each. To cut seven or eight sheaves was considered a good day's work for a shearer. After the introduction of the scythe (1810), the best men cut the corn, the women gathered it into sheaves, and made the bands, while younger men, as a rule, bound and stooked the sheaves. The bandster could claim a kiss from the gatherer for each band whose knot slipped in the binding."

From the singing of James Grant of Aberdour, Banffshire.

Jock Hawk's Adventure in Glasgow — The basic bothy theme of the farm-servant exploited by the rich farmer is, in this ballad, altered slightly to become the farm-servant exploited by city-slickers. The general bothy pattern, however, remains unchanged and, as usual, no element of self-pity is allowed to interfere with the humour.

The Brewer Laddie — The forsaken and jilted heroes (and heroines) of the bothy ballads rarely die for love; instead, they meet misfortune head on and, with a good deal of sound sense, start looking around for another sweetheart. It has been suggested that The Brewer Laddie is a bothy adaptation of an older song and this may well be the case.

Learned from my father and collated with versions in Ord's Bothy Songs and Ballads and Kidson's Traditional Tunes.

The Wine Blew the Bonnie Lassie's PlaidIe Awa' — In a note given to a text of this song in Robert Ford's 'Vagabond Ballads it is stated: "My friend, Mr. D. Kippen of Crieff has it that the song was composed by an Irishman who lived in Crieff near to the Cross in the early years of the present century who was known by the name of Blind Bob." In most printed versions only a single refrain is given but country singers prefer to vary the chorus.

From the singing of Hughie Graham of Galloway.

The Monymusk Lads — Rural courtship was a popular theme with the bothy singers and in this song the story is embellished with some rather sharp comment on the class structure. Learned from print: Ord's Bothy Songs and Ballads.

The Muckin' O' Geordie's Byre — This epic of domestic upheaval owes its title to a much older song (Scots Musical Museum No. 96) and its tune has been adapted from a Gaelic melody. It is one of the few bothy ballads which have gained currency outside the bothy areas.

From the singing of Jimmy MacBeth of Elgin.

Bogie's Bonny Belle — It is not often that the heroes of the bothy songs are allowed to expose their passion, their anger or their resentment, the direct expression of such feelings being either avoided entirely or burlesqued. Irony, satire and slapstick humor are the usual weapons of the bothy singer and when, as in Bogie' s Bonny Belle, he abandons them in favour of the frontal assault, the effect is startling.

From the singing of Jimmy Gray of MacDuff, Banffshire.

Lamachree And Megrum — The bothy ballads generally fall into a fairly simple structural pattern, consisting of four-line stanzas (A-B-A-B rhyming system) often followed by a chorus. The song given here is unique in that it makes use of a form more common to the traditional ballad — that is, a four-line stanza in which the 2nd and 4th lines are refrains.

The similarity to the traditional ballad form is further strengthened by a homonymic use of place names, almost amounting to incremental repetition and through the use of a strongly hypnotic melody.

Learned from print (Miscellanea of the Rymour Club of Edinburgh)

The Road and The Miles to Dundee — This singularly innocent song is deservedly popular throughout the whole of northeast Scotland. It is one of those pieces which belongs to that part of a social gathering when drink and good fellowship demand the somewhat pleasant feelings of nostalgia which such a song can create.

From the singing of Rob Donald of Gardenstown, Banffshire.

The Lothian Hairst — There is interesting reference to this song in Ord's introduction to Bothy Songs and Ballads: "Upwards of half a century ago for harvest contractors to. visit the Lothians during the summer and undertake to cut, gather and stook grain crops at an arranged price per acre. The contractor, or maister as he was called.by the workers, engaged a foreman, who was held responsible by the contractor for carrying out the various contracts. The foreman was, in every case, to act like 'Logan' in the song and to see that the male reapers visiting their female co-workers at their bothies terminated their visits at a given hour."

Learned from print: Miscellanea of the Rymour Club of Edinburgh.

It Happened on A Day — In the Brewer Laddie the jilted lover shrugs his shoulders ate fate and finds himself a new sweetheart. In this song it is the girl who is jilted but she too shows that she is capable of coping with the situation.

From James Grant of Aberdour, Banffshire.

I'm A Working Chap — It is only rarely that the bothy ballad essays a direct sociological comment and when the attempt is made the result is not usually a happy one. The Working Chap is reminiscent of the style found in the writings of 'the fustian philosophers' who helped to pioneer the British socialist movement. "The puir needle woman … on the wa'," mentioned in the second verse, is a reference to the once ubiquitous daguerretype inspired by Thomas Hood's Song of a Shirt.

Learned from print: Ord's Bothy Songs and Ballads.

Johnny Sauoster — According to Gavin Greig who collected the first printed version of this fine song, Johnny Sangster was the work of William Scott who was born in Fetterangus in the parish of Old Deer, Aberdeenshire in 1785. Scott who began life as a herd laddie subsequently moved to Aberdeen where he was apprenticed to a tailor. Later, he worked, for a time, in London and after visiting America returned to Old Deer where he spent the remainder of his life.

Learned from print: Miscellanea of the Rymour Club, Edinburgh.

Drumdelgle — In spite of being a local song, that is, a song describing a particular set of conditions in a particular place, Drumdelgie has achieved vide popularity throughout the world of Eastern Scotland and if farm-servants can be said to have a national anthem then this is it.

Learned from Jimmie MacBeth of Elgin.

She Was A Rum One — "That's a gey rauch (rough) sang" commented Rob Donald the Gamrie shepherd after hearing it for the first time, "but" he went on, "it gets richt tae the hairt o' the maitter." And he was right.

From Jeannie Robertson of Aberdeen.