|

|

|

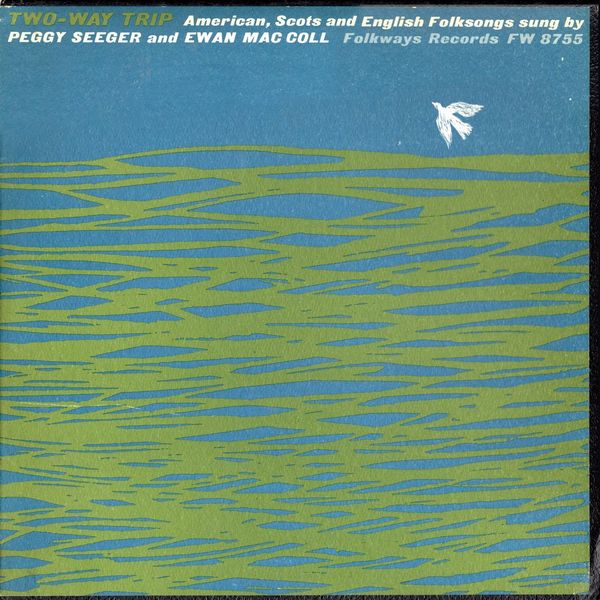

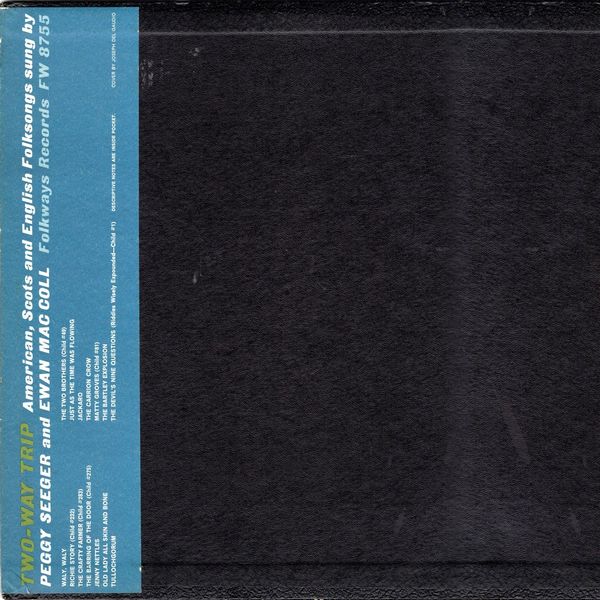

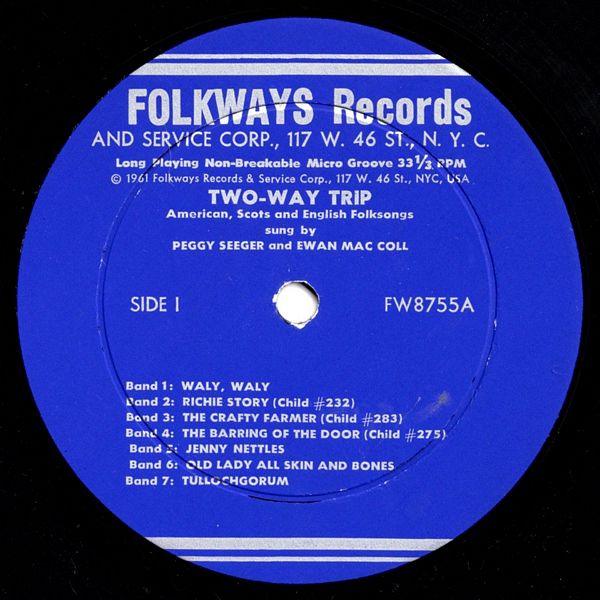

Sleeve Notes

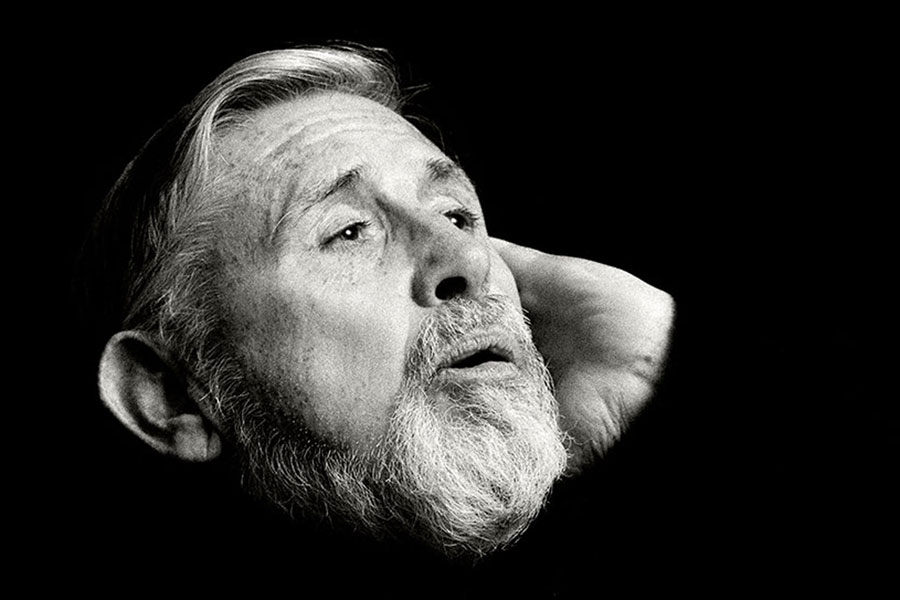

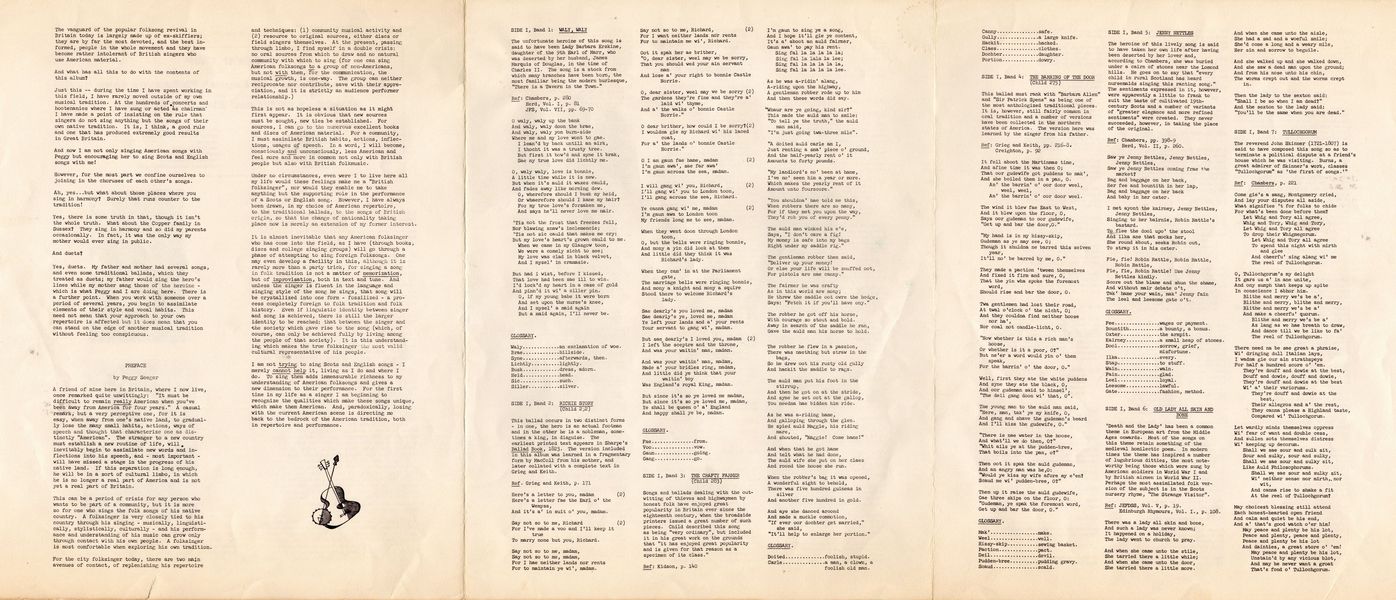

PREFACE by Ewan MacColl

I mostly sing Scots and English songs. The Scots material was part of the background of ray childhood, the English I began to acquire during my adolescence and have gone on adding to my store ever since. The Scots songs are closest to me, with the Liverpool shanties and forebitters running them a close second.

As for American folkmusic, my first contact with it was during the late thirties when I heard some of the Library of Congress recordings broadcast in the first B.B.C. folksong series. I can still remember the tremendous impact they made on me, and still recapture something of the initial excitement that was roused in me by hearing Woodie Guthrie, Blind Willie Johnson and that most superb of all folksong stylists, Mrs. Texas Gladden.

During the years that followed I learned scores of American songs and ballads and made them work for my pleasure until they could work no more. The pseudo-American accent which I acquired by watching gangsters and western gunmen flicker across the threadbare screens of a hundred flea-pits, twisted the songs into mere parodies of themselves until, in the end, I began to develop a hearty dislike for my own voice. I returned to the songs I knew, the songs I had grown up with.

Some fifteen or sixteen years later, in 1954, I was to see young folks all over Britain behaving similarly … only more so. With me it was Texas Gladden, with them it was Leadbelly.' This was during the short-lived age of skiffle, when the kids of Glasgow, Hull and Manchester discovered the guitar and the tea-chest bass, when the lads of Liverpool, Leeds and London rolled their own, tried to unlearn reading and writing and looked at you with the hyperopic gaze of men whose eyes have grown dim with staring over the eternal deserts of Arizona, Utah and the Bronx; it was the time when the chicks and scrubbers began to talk out of the sides of their mouths and to stare at you with contemptuous eyes because you hadn't been in a chaingang; it was the time when the addicts built twelve-string guitars in the body-building shops of the Ford factories and when the roaring-boys of Tin-Pan-Alley couldn't make up their minds as to whether they should get in on the act or register for a long course of Electrical Convulsive Shock treatment.

Well, finally they made up their minds and took skiffle over, gave it a haircut and a shampoo and sent the results rolling down the conveyor-belt of the pop industry. It didn't last long, just long enough to produce the inevitable reaction. So the kids hocked their cheap guitars and moved out of the cellars and the upstairs rooms of number- less pubs and looked around for something else that they could identify themselves with. Many of them, moved by the herd instinct found refuge in 'the rock' joints, others found their way into the jazz clubs and the rest began to form folksong clubs.

The vanguard of the popular folksong revival in Britain today is largely made up of ex-skifflers; they are by far the most devoted, and the best informed, people in the whole movement and they have become rather intolerant of British singers who use American material.

And what has all this to do with the contents of this album?

Just this — during the time I have spent working in this field, I have rarely moved outside of my own musical tradition. At the hundreds of concerts and hootenanies where I have sung or acted as chairman I have made a point of insisting on the rule that singers do not sing anything but the songs of their own native tradition. It is, I think, a good rule and one that has produced extremely good results in Great Britain.

And now I am not only singing American songs with Peggy but encouraging her to sing Scots and English songs with me!

However, for the most part we confine ourselves to joining in the choruses of each other's songs.

Ah, yes … but what about those places where you sing in harmony? Surely that runs counter to the tradition!

Yes, there is some truth in that, though it isn't the whole truth. What about the Copper family in Sussex? They sing in harmony and so did my parents occasionally. In fact, it was the only way my mother would ever sing in public.

And duets?

Yes, duets. My father and mother had several songs, and even some traditional ballads, which they treated as duets; my father would sing the hero's lines while my mother sang those of the heroine — which is what Peggy and I are doing here. There is a further point. When you work with someone over a period of several years, you begin to assimilate elements of their style and vocal habits. This need not mean that your approach to your own repertoire is affected but it does mean that you can stand on the edge of another musical tradition without feeling too conspicuous.

PREFACE by Peggy Seeger

A friend of mine here in Britain, where I now live, once remarked quite unwittingly: "It must be difficult to remain really American when you've been away from America for four years." A casual remark, but a very perceptive one, for it is easy, when away from one's native land, to gradually lose the many small habits, actions, ways of speech and thought that characterize one as distinctly "American". The stranger to a new country must establish a new routine of life, will inevitably begin to assimilate new words and inflections into his speech, and — most important — will have missed a stage in the progress of his native land. If this separation is long enough, he will be in a sort of cultural limbo, in which he is no longer a real part of America and is not yet a real part of Britain.

This can be a period of crisis for any person who wants to be part of a community, but it is more so for one who sings the folk songs of his native country. A folksinger is very closely tied to his country through his singing — musically, linguistically, stylistically, culturally — and his performance and understanding of his music can grow only through contact with his own people. A folksinger is most comfortable when exploring his own tradition.

For the city folksinger today, there are two main avenues of contact, of replenishing his repertoire and techniques: (l) community musical activity and (2) resource to original sources, either discs or field singers themselves. At the present, passing through limbo, I find myself in a double crisis: no oral sources from which to draw and no natural community with which to sing (for one can sing American folksongs to a group of non-Americans, but not with them, for the communication, the musical growth, is one-way. The group can neither reciprocate nor contribute, save with their appreciation, and it is strictly an audience performer relationship.)

This is not as hopeless a situation as it might first appear. It is obvious that new sources must be sought, new ties be established. For sources, I can go to the numerous excellent books and discs of American material. For a community, I must assimilate British habits, actions, inflections, usages of speech. In a word, I will become, consciously and unconsciously, less American and feel more and more in common not only with British people but also with British folkmusic.

Under no circumstances, even were I to live here all my life would these feelings make me a "British folksinger", nor would they enable me to take anything but the supporting role in the performance of a Scots or English song. However, I have always been drawn, in my choice of American repertoire, to the traditional ballads, to the songs of British origin, so that the change of nationality taking place now is merely an extension of my former interest.

It is almost inevitable that any American folksinger who has come into the field, as I have (through books, discs and college singing groups) will go through a phase of attempting to sing foreign folksongs. One may even develop a facility in this, although it is rarely more than a party trick, for singing a song in folk tradition is not a matter of memorization, but of improvisation, both in text and tune. And unless the singer is fluent in the language and singing style of the song he sings, that song will be crystallized into one form — fossilized — a process completely foreign to folk tradition and folk history. Even if linguistic identity between singer and song is achieved, there is still the larger identity to be reached: that between the singer and the society which gave rise to the song (which, of course, can only be achieved fully by living among the people of that society). It is this understanding which makes the true folksinger the most valid cultural representative of his people.

I am not trying to sing Scots and English songs — I merely cannot help it, living as I do and where I do. To sing them adds immeasurable richness to my understanding of American folksongs and gives a new dimension to their performance. For the first time in my life as a singer I am beginning to recognize the qualities which make these songs unique, which make them American. And, paradoxically, losing with the current American scene is directing me back to the bedrock of the American tradition, both in repertoire and performance.

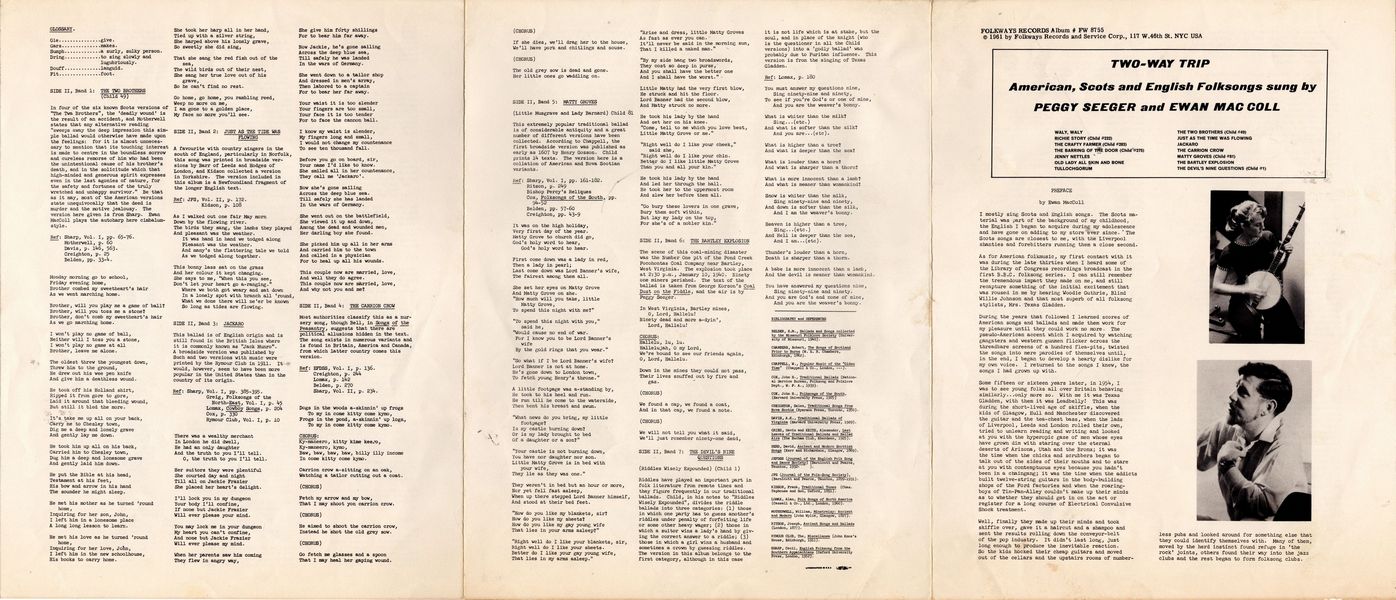

Waly, Waly — The unfortunate heroine of this song is said to have been Lady Barbara Erskine, daughter of the 9th Earl of Marr, who was deserted by her husband, Janes Marquis of Douglas, in the time of Charles II. The song is a stock from which many branches have been bora, the most familiar being the modern burlesque, "There is a Tavern in the Town."

Richie Story — (Child 232) This ballad occurs in two distinct forms — in one, the hero is an actual footman and in the other he is a nobleman, sometimes a king, in disguise. The earliest printed text appears in Sharpe's Ballad Book, 1823. The version included

The Crafty Farmer — (Child 283) Songs and ballads dealing with the out-witting of thieves and highwaymen by honest folk have enjoyed great popularity in Britain ever since the eighteenth century, when the broadside printers issued a great number of such pieces. Child described this song as being "very ordinary" but included it in his great work on the grounds that "it has enjoyed great popularity and is given for that reason as a specimen of its class."

The Barring of The Door — {Child 275) This ballad must rank with "Barbara Allen" and "Sir Patrick Spens" as being one of the most anthologized traditional pieces. It is, however, still fairly common in oral tradition and a number of versions have been collected in the northern states of America. The version here was learned by the singer from his father.

Jenny Nettles — The heroine of this lively song is said to have taken her own life after having been deserted by her lover and, according to Chambers, she was buried under a cairn of stones near the Lomond hills. He goes on to say that "every child in rural Scotland has heard nursemaids singing this ranting song." The sentiments expressed in it, however, were apparently a little to frank to suit the taste of cultivated 19th-century Scots and a number of variants of "greater elegance and more refined sentiments" were created. They never succeeded, however, in taking the place of the original.

Old Lady All Skin and Bone — 'Death and the Lady' has been a common theme in European art from the Middle Ages onwards. Most of the songs on this theme retain something of the medieval homilectic poem. In modern times the theme has inspired a number of lugubrious ditties, the most noteworthy being those which were sung by American soldiers in World War I and by British airmen in World War II.Perhaps the most assimilated folk version of the subject is in the Scots nursery rhyme, "The Strange Visitor".

Tullochgorum — The reverend John Skinner (1721-1807) is said to have composed this song so as to terminate a political dispute at a friend's house which he was visiting. Burns, a great admirer of Skinner's work, classes "Tullochgorum" as 'the first of songs.'"

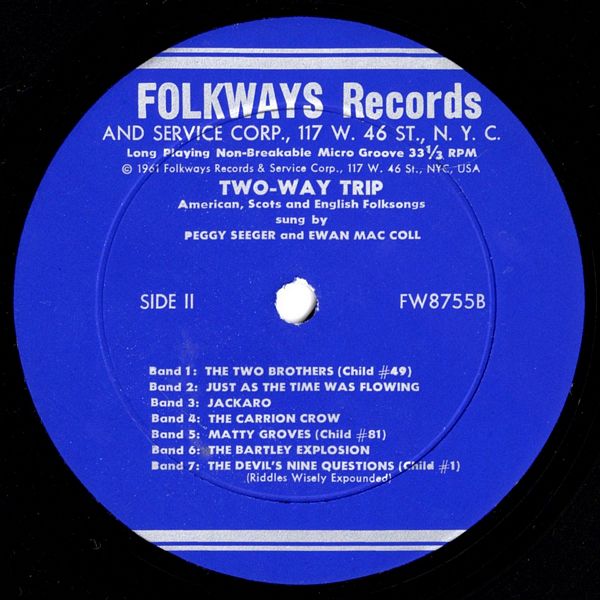

The Two Brothers — (Child 49) In four of the six known Scots versions of "The Twa Brothers", the 'deadly wound' is the result of an accident, and Motherwell states that any alternative reading "sweeps away the deep impression this simple ballad would otherwise have made upon the feelings: for it is almost unnecessary to mention that its touching interest is made to centre in the boundless sorrow and cureless remorse of him who had been the unintentional cause of his brother's death, and in the solicitude which that high-minded and generous spirit expresses even in the last agonies of nature, for the safety and fortunes of the truly wretched and unhappy survivor." Be that as it may, most of the American versions state unequivocally that the deed is murder and the motive jealousy. The version here given is from Sharp. Ewan MacColl plays the autoharp here cimbalum-style.

Just as The Tide Was Flowing — A favourite with country singers in the south of England, particularly in Norfolk, this song was printed in broadside versions by Barr of Leeds and Hodges of London, and Kidson collected a version in Yorkshire. The version included in this album is a Newfoundland fragment of the longer English text.

Jackaro — This ballad is of English origin and is still found in the British Isles where it is commonly known as "Jack Munro".A broadside version was published by Such and two versions with music were printed by the Rymour Club in 1911* It would, however, seem to have been more popular in the United States than in the country of its origin.

The Carrion Crow — Most authorities classify this as a nursery song, though Bell, in Songs of the Peasantry, suggests that there are political allusions hidden in the text. The song exists in numerous variants and is found in Britain, America and Canada, from which latter country comes this version.

Matty Groves — (Little Musgrave and Lady Barnard) Child 8l This extremely popular traditional ballad is of considerable antiquity and a great number of different versions have been collected. According to Chappell, the first broadside version was published as early as 1607 by Henry Gosson. Child prints 14 texts. The version here is a collation of American and Nova Scotian variants.

The Bartley Explosion — The scene of this coal-mining disaster was the Number One pit of the Pond Creek Pocohontas Coal Company near Bartley, West Virginia. The explosion took place at 2:30 p.m., January 10, 1940. Ninety-one miners perished. The text of the ballad is taken from George Korson's Coal Dust on the Fiddle, and the air is by Peggy Seeger.

The Devil's Nine Questions — (Riddles Wisely Expounded) (Child l) Riddles have played an important part in folk literature from remote times and they figure frequently in our traditional ballads. Child, in his notes to "Riddles Wisely Expounded", divides the riddle ballads into three categories: (1) those in which one party has to guess another's riddles under penalty of forfeiting life or some other heavy wager; (2) those in which a suitor wins a lady's hand by giving the correct answer to a riddle; (3) those in which a girl wins a husband and sometimes a crown by guessing riddles.The version in this album belongs to the first category, although in this case it is not life which is at stake, but the soul, and in place of the knight (who is the questioner in all the Child versions) into a 'godly ballad' was probably due to Puritan influence. This version is from the singing of Texas Gladden.