|

|

Sleeve Notes

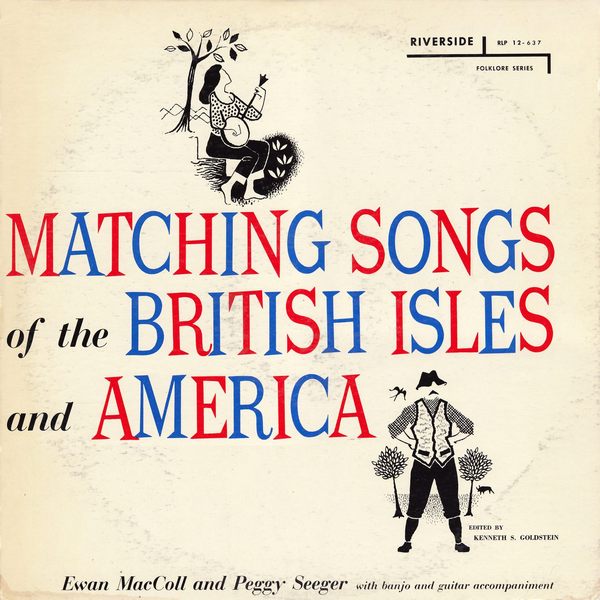

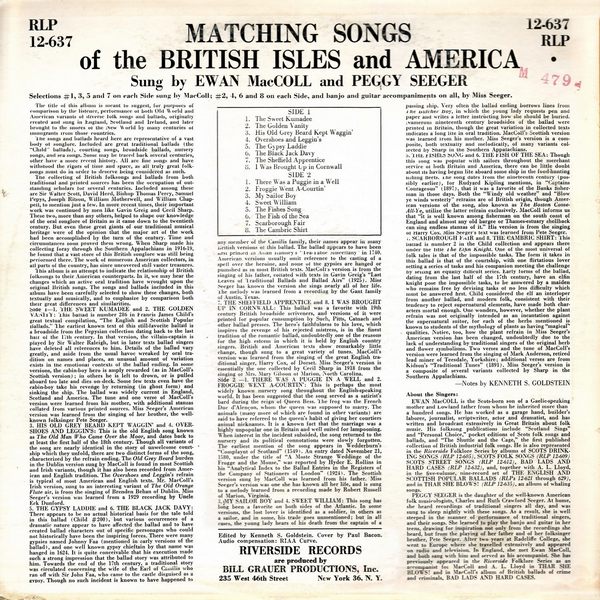

The title of this album is meant to suggest, for purposes of comparison by the listener, performative of both Old World and American variants of diverse folk songs and ballads, originally created and sung in England, Scotland and Ireland, and later brought to the snores of the New World by many centuries of immigrants from those countries.

The songs and ballads heard here are representative of a vast body of songlore. Included are great traditional ballads (the "Child" ballads), courting songs, broadside ballads, nursery songs, and sea songs. Some may be traced back several centuries, other have a more recent history. All are fine songs and have withstood the rigors of time and space, as all truly great folksongs must do in order to deserve being considered as such.

The collecting of British folksongs and ballads from both traditional and printed sources has been the occupation of outstanding scholars tor several centuries. Included among these are Sir Walter Scott, David Herd, Bishop Thomas Percy, Samuel Pepys, Joseph Ritson, William Motherwell, and William Chappell, to mention just a few. In more recent times, their important work was continued by men like Gavin Greig and Cecil Sharp. These two, more than any others, helped to shape our knowledge of the oral songlore of Britain as it came down to the twentieth century. But even these great giants of our traditional musical heritage were of the opinion that the major art of the work had been accomplished by the turn of the century. Time and circumstances soon proved them wrong. When Sharp made his collecting foray through the Southern Appalachians in 1916-19, he found that a vast store of this British songlore was still being performed there. The work of numerous American collectors, in all parts of the country, has since uncovered still vaster treasures.

This album is an attempt to indicate the relationship of British folksongs to their American counterparts. In it, we may hear the changes which an active oral tradition have wrought upon the original British songs. The songs and ballads included in this album have been carefully selected to show these changes, both textually and musically, and to emphasize by comparison both their great differences and similarities.

THE SWEET KUMADEE and THE GOLDEN VANITY:

This ballad is number 286 in Francis James Child's great textual compilation, "The English and Scottish Popular Ballads." The earliest known text of this still-favorite ballad is a broadside from the Pepysian collection dating back to the last hall of the 17th century. In that version, the villain-captain is played by Sir Walter Raleigh, but in later texts ballad singers have deleted all references to him. Details of the ballad vary greatly, and aside from the usual havoc wreaked by oral tradition on names and places, an unusual amount of variation exists in the emotional contexts of the ballad ending. In some versions, the cabin-boy hero is amply rewarded (as in MacColl's Scottish version) ; in others he is left to drown, or is pulled aboard too late and dies on deck. Some few texts even have the cabin-boy take his revenge by returning (in ghost form) and sinking the ship. The ballad was widely current in England, Scotland and America. The tune and one verse of MacColl's version were learned from his mother, with additional stanzas collated from various printed sources. Miss Seeger's American version was learned from the singing of her brother, the well-known folksinger Pete Seeger.

HIS OLD GREY BEARD KEPT WAGGIN' and OVERSHOES AND LEGGIN'S:

This is the old English song known as The Old Man Who Came. Over the Moor, and dates back to at least the first half of the 18th century. Though all variants of the song are nearly identical in the story of unwelcome courtship which they unfold, there are two distinct forms of the song, characterized by the refrain ending. The Old Grey Beard burden in the Dublin version sung by MacColl is found in most Scottish and Irish variants, though it has also been recorded from American and English tradition. The Overshoes and Leggin's refrain is typical of most American and English texts. Mr. MacColl's Irish version, sung to an interesting variant of The Old Orange Flute air, is from the singing of Brenden Behan of Dublin. Miss Seeger's version was learned from a 1929 recording by Uncle Eck Dunford.

THE GYPSY LADDIE and THE BLACK JACK DAVY:

There appears to be no actual historical basis for the tale told in this ballad (Child #200), but various occurrences of a dramatic nature appear to have affected the ballad and to have created ballad characters out of specific personages who could not historically have been the inspiring forces. There were many gypsies named Johnny Faa (mentioned in early versions of the ballad), and one well known gypsy chieftain by that name was hanged in 1624. It is quite conceivable that his execution made such a strong impression that the ballad story was attributed to him. Towards the end of the 17th century, a traditional story was circulated concerning the wife of the Earl of Cassilis who ran off with Sir John Faa, who came to the castle disguised as a gypsy. Though no such incident is known to have happened to any member of the Cassilis family, their names appear in many British versions of this ballad. The ballad appears to have been first printed in Anan Ramsey's "Tea-Table miscellany" in 1740. American versions usually omit reference to the casting of a spell over the heroine, and none of the gypsies are hanged or punished as in most British texts. MacColl's version is from the singing of his father, collated with texts in Gavin Greig's "Last Leaves of Traditional Ballads and Ballad Airs" (1925). Miss Seeger has known the version she sings nearly all of her life. The melody was learned from a recording by the Gant family of Austin, 'Texas.

THE SHEFFIELD APPRENTICE and I WAS BROUGHT UP IN CORNWALL:

This ballad was a favorite with 19th century British broadside scriveners, and versions of it were printed for popular consumption by Such, Pitts, Catnach and other ballad presses. The hero's faithfulness to his love, which inspires the revenge of his rejected mistress, is in the finest tradition of the romantic ballad, undoubtedly one of the reasons for the high esteem in which it is held by English country singers. British and American texts show remarkably little change, though sung to a great variety of tunes. MacColl's version was learned from the singing of the great English traditional singer, Harry Cox, of Dorset. Miss Seeger's version is essentially the one collected by Cecil Sharp in 1918 from the singing of Mrs. Mary Gibson of Marion, North Carolina.

THERE WAS A PUGGIE IN A WELL and FROGGIE WENT A-COURTIN':

This is perhaps the most widely known nursery song throughout the English-speaking world. It has been suggested that the song served as a satirist's bard during the reign of Queen Bess.The frog was the French Duc d'Alencon, whom the queen was supposed to marry. The animals (many more of which are found in other variants) are said to have referred to the queen's habit of giving her courtiers animal nicknames. It is a known fact that the marriage was a highly unpopular one in Britain and well suited for lampooning. When interest in the incident subsided, the song returned to the nursery and its political connotations were slowly forgotten. The earliest mention of the song appears in Wedderburn's "Complaynt of Scotland" (1549). An entry dated November 21, 1580, under the title of "A Moste Strange Weddinge of the Frogge and the Mouse," was reported by Hyder E. Rollins in his "Analytical Index to the Ballad Entries in the Registers of the Company of Stationers of London" (1924). The Scottish version sung by MacColl was learned from his father. Miss Seeger's version was one she has known all her life, and is sung to a melody learned from a recording made by Robert Russell of Marion, Virginia.

MY SAILOR BOY and SWEET WILLIAM:

This song has long been a favorite on both sides of the Atlantic. In some versions, the lost lover is identified as a soldier, in others as a sailor, and in some, his trade goes unmentioned; but in all cases, the young lady hears of his death from the captain of a passing ship. Very often the ballad ending borrows lines from The Butcher Boy, in which the young lady requests pen and paper and writes a letter instructing how she should be buried. numerous nineteenth century broadsides of the ballad were printed in Britain, though the great variation in collected texts indicates a long lite in oral tradition. MacColl's Scottish version was learned from his mother. Miss Seeger's version is a composite, both textualiy and melodically, of many variants collected by Sliarp in the Southern Appalachians.

THE FISHES SONG and THE FISH OF THE SEA:

Though this song was popular with sailors throughout the merchant service of both Britain and America, there can be little doubt about its having begun life aboard some ship in the food-hunting fishing fleets. The song dates from the nineteenth century (possibly earlier), tor Rudyard Kipling mentions, in "Captains Courageous" (1897), that it was a favorite of the Banks fisherman in those days. Both the "Windy old weather" and "Blow ye winds westerly" refrains are of British origin, though American versions of the song, also known as The Boston Come-All-Ye, utilize the latter refrain exclusively. MacColl informs us that "it is well known among fisherman on the south coast of England and almost any old bargee or Thames-estuary shellback can sing endless stanzas of it." His version is from the singing of Harry Cox. Miss Seeger's text was learned from Pete Seeger.

SCARBOROUGH FAIR and THE CAMBRIC SHIRT:

This ballad is number 2 in the Child collection and appears there under the title 1 he Elfin Knight. One of the most universal of folk tales is that of the impossible tasks. The form it takes in this ballad is that of the courtship, with one flirtatious lover setting a series of tasks and his companion meeting the challenge by setting an equally difficult series. Early forrns of the ballad, dating from the last half of the 17th century, have an elfin knight pose the impossible tasks, to be answered by a maiden who remains free by devising tasks of no less difficulty which must be answered first. Child considered the elf an interloper from another ballad, and modern folk, consistent with their tendency to reject supernatural elements, have made both characters mortal enough. One wonders, however, whether the plant refrain was not originally intended as an incantation against the supernatural suitor, tor each of the herbs mentioned is known to students of the mythology of plants as having "magical" qualities. Notice, too, how the plant refrain in Miss Seeger's American version has been changed, undoubtedly due to the lack of understanding by traditional singers of the original herb and flower symbolisms. Two verses and the tune of MacColl's version were learned from the singing of Mark Anderson, retired lead miner of Teesdale, Yorkshire; additional verses are from Kidson's "Traditional Tunes" (1891). Miss Seeger's version is a composite of several variants collected by Sharp in the Southern Appalachians.

— Notes by KENNETH S. GOLDSTEIN

About the Singers:

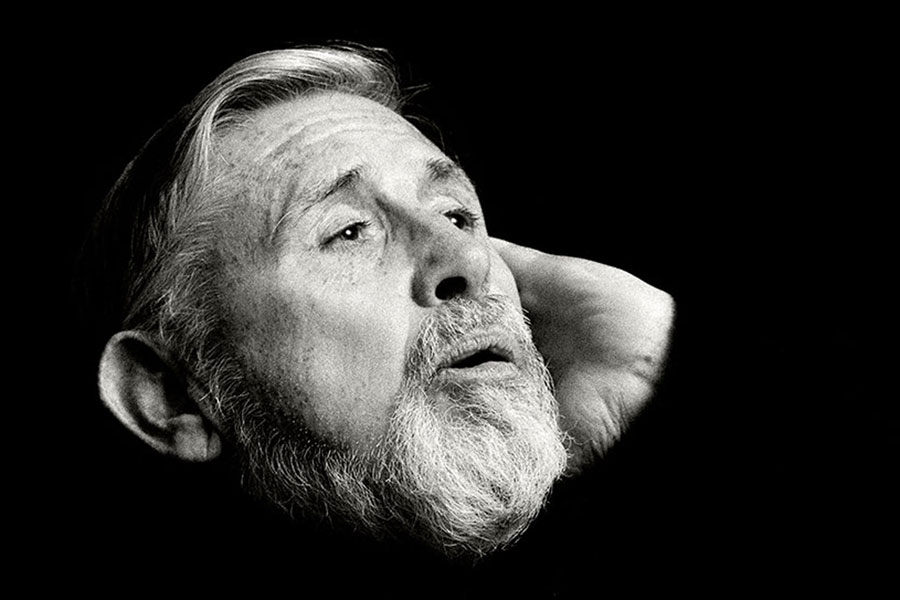

EWAN MacCOLL is the Scots-born son of a Gaelic-speaking mother and Lowland father from whom he inherited more than a hundred songs. He has worked as a garage hand, builder's laborer, journalist, scriptwriter, actor and dramatist, and has written and broadcast extensively in Great Britain about folk music. His folksong publications include "Scotland Sings" and "Personal Choice," pocket editions of Scots folk songs and ballads, and "The Shuttle and the Cage," the first published collection of British industrial folk songs. He is also represented in the Riverside Folklore Series by albums of SCOTS DRINKING SONGS (RLP 12-605), SCOTS FOLK SONGS (RLP 12-609) SCOTS STREET SONGS (RLP 12-612), BAD LADS AND HARD CASES (RLP 12-632), and, together with A. L. Lloyd, in the five-volume, nine-record set of THE ENGLISH AND SCOTTISH POPULAR BALLADS (RLPs 12-621 through 629), and in THAR SHE BLOWS! (RLP 12-635), an album of whaling songs.

PEGGY SEEGER is the daughter of the well-known American folk musicologists, Charles and Ruth Crawford Seeger. At home, she heard recordings of traditional singers all day, and was sung to sleep nightly with these songs. As a result, she is well steeped in the manner of performance of traditional singers, and their songs. She learned to play the banjo and guitar in her teens, drawing for inspiration not only from the recordings she heard, but from the playing of her father and of her folksinger brother, Pete Seeger. After two years at Radcliffe College, she went to Europe where she travelled extensively and appeared on radio and television. In England, she met Ewan MacColl, and both sang with him and served as his accompanist. She has previously appeared in the Riverside Folklore Series as an accompanist for MacColl and A. L. Lloyd in THAR SHE BLOWS! and in MacColl's album of British ballads of crime and criminals, BAD LADS AND HARD CASES.