|

|

|

| more images |

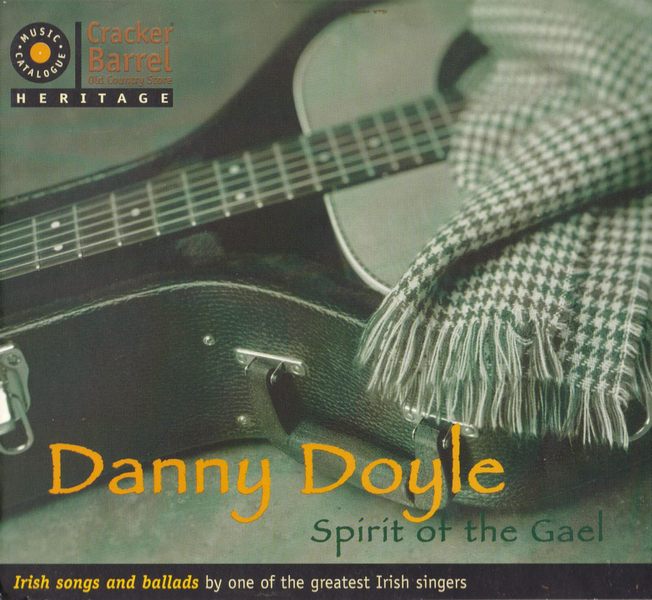

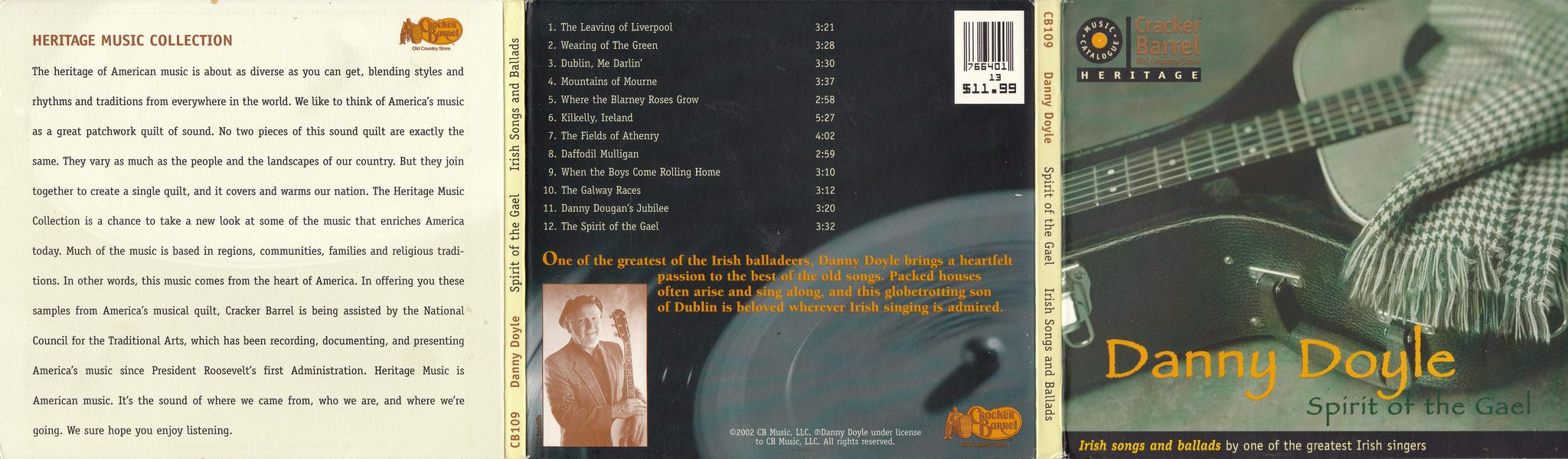

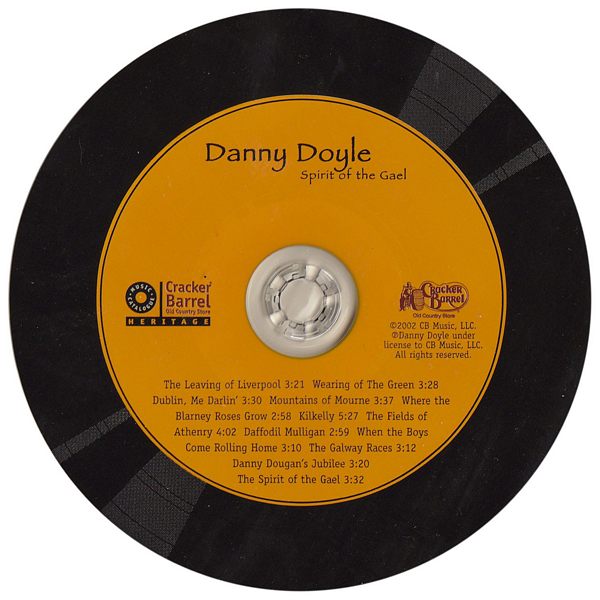

Sleeve Notes

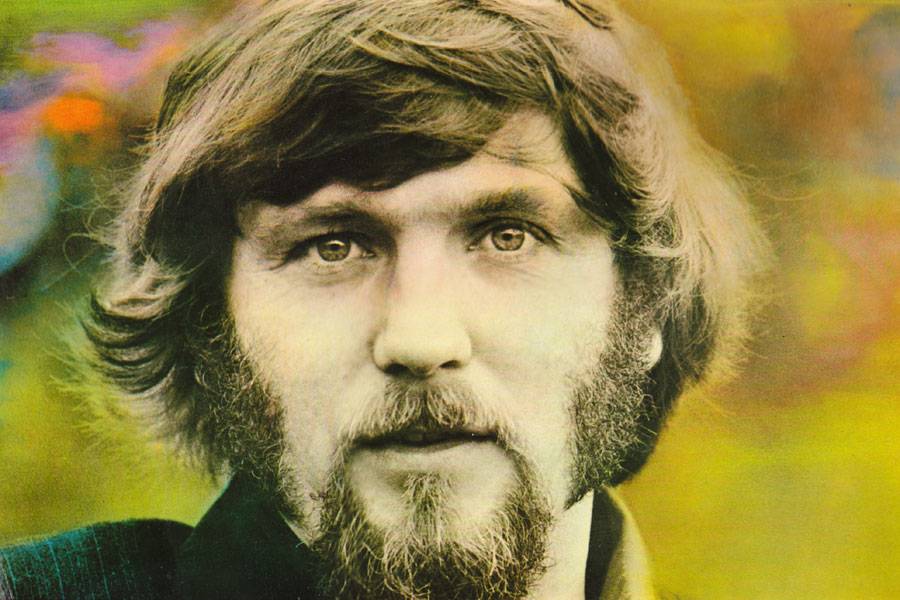

Dublin-born Danny Doyle is a walking encyclopedia of Irish song. We are pleased that he shared his thoughts about the music through these liner notes.

I was born and raised in Ireland, a place of memories and plentiful ghosts, in Dublin town hard by the banks of the Liffey's Guinness-coloured waters.

The city was a great teacher, giving me history and legend, stories of the commonplace and heroic, legends more real than dull facts; the bawdy, rowdy grist of the ballad maker's mill.

The poet Brendan Kennealy wrote that "All songs are living ghosts and long for a living voice." I sometimes visualize the living voice of my great-grandmother sitting in the chimney corner of her single room in the fetid slums of Dublin, conjuring into spectral life, through song and poem, heroes, rebels, rogues and lovers, the song-time history of Ireland.

Our ballads are an expressive reflection of the people who gave them voice—a folk symphony of melody and lyric, full of sly humour, wild and soft sadness, gentle defiance, roaring resistance and a raucous longing for life. They bind us to our past. I've spent a lifetime being shadowed by this Spirit Of The Gael. What a rich musical haunting it has been.

Across the Irish Sea from Dublin lies Liverpool, the "Second Capital of Ireland," so called because of the hundreds of thousands of Irish who settled there over the centuries—countless Liverpudlians proudly acknowledge their Irish ancestry. The Leaving of Liverpool dates from the mid 1800s. The ship and captain mentioned in the song (he, a reputed tyrant) worked the passage between England and America. This was recorded live at O'Flaherty's Irish Pub in New Orleans.

The Wearing of the Green voices, with a restrained and simple dignity, the powerful aspirations of a downtrodden people, the immutable defiance and tragedy of a centuries-old struggle. It was one of the songs sung by the hordes of young Irishmen who marched to death in the failed rebellion of 1798. I learned this and many another from my great-grandmother, who admonished us to "Always forgive, but never forget." We sing to remember.

Dublin, Me Darlin' treats the subject of emigration in affectionate, even happy tones, the antithesis of some of our more sentimental songs of parting. Our long Diaspora is so imprinted on the Irish consciousness that in any given pub, you'll likely encounter groups of young Irish men and women lamenting Ireland, missing Ireland, crying into their drinks about Ireland, comforting each other about Ireland. And this just in Dublin!! I found the song in an old book and set the lyric to a lilting west of Ireland melody, "Fineen The Rover."

Percy French, a 19th century songsmith and poet, was also a painter in watercolours. Some of his musical work, that of a comic nature, depicted the Irish as quaint, likable but amusing buffoons. These songs have been eschewed by Irish folk singers, but in their time they appealed mostly to a middle to upper class English and Irish audience, whose relation to the lower class Irish was generally one of master and servant. In fairness to French, he wrote some heartfelt pieces. Mountains of Mourne is one.

The proprietor of the music pub in the Dublin Mountains was Kerryman Mick McCarthy, well-known for the words, "Twas a bad night, no one turned up, there is no money to pay you." On one such night, Mick had the amazing audacity to pay a famous tenor by fobbing off on him a burned-out greyhound that had never won a race. On another, as he approached me with that look on his face, I knew that at a moment like this, extracting money from Mick was like squeezing blood from a turnip. I settled for a few pints and a plate of fried chicken. But I met Paddy Browne that night, who sang for me Where the Blarney Roses Grow. I was well paid.

In his parents' attic in Washington DC, Peter Jones found a bundle of old letters. They dated from 1860 up to the 1890s and came from Kilkelly, County Mayo, in the west of Ireland. In the horror of the Great Famine, 1845 - 1847, Mayo suffered the greatest calamity. Millions died or fled to America, away from a country they considered cursed. Taking lines from his ancestor's letters Peter made this powerful and stunning song, Kilkelly, Ireland.

In the midst of the Great Famine, more than enough food to keep the starving populace alive was exported from Ireland. The London authorities justified their initial unresponsiveness to the suffering on grounds that they did not wish to interfere with commerce or capitalism. The Fields of Athenry was written by my dear friend Pete St. John, who keeps giving me wonderful songs. Based on a true story about a young man who sets out to thieve the Queen's grain stores, the song has sung its way into the hearts of people the world round.

In the humdrum world of Ireland in the forties and fifties, the exuberance of the Dublin theatre stretched like a rainbow across the dreariness of our damp and impoverished lives. The comedian and vaudevillian, Jimmy O'Dea, was the darling of the playhouses. My father took me to the theatre often and there I first heard O'Dea sing of Daffodil Mulligan, a Dublin street vendor, a profession not unknown in our family. The theatre in those days was a great bargain, matinee admittance costing less than a shilling. The Dublin actor Noel Purcell said, "Sure, for God's sake, twas cheaper than lightin' a fire."

When I left Ireland for America my family had a going away party for me. I know, because they wrote and told me about it later. Seriously though, when I said goodbye, I uttered the words that emigrants have spoken through the centuries; "I'll be back." Well, I'm one of the lucky ones, for I've come rolling home to Ireland many times. Years later, a Dublin woman who had been in America illegally for six months asked me if I got homesick. I told her I did. She said, "What's it like?" There is no answer to that, so I sang her When the Boys Come Rolling Home. On this recording I sing it with my sister Geraldine, or "the holy terror" as my Mother used to call her.

My friend Fergal O'Connell's mother and her pal Madge decided to go to the Galway Races. They soon got bored with the horse racing so off they rambled out past the show-ring, the horse paddocks and barns, along a grassy laneway leaving the race crowds far behind. Mrs. O'Connell began complaining that she needed to visit the Ladies room badly. Madge said, "Look, we're out in the middle of the country. If you must go, I'll keep a look-out." As Mrs. O'Connell squatted in mid-relief behind a hedge she heard the approaching thunder of hooves, and seconds later a dozen racehorses and their cursing riders came hurtling over her head. She said later the language out of the jockeys as they urged their mounts on was disgraceful and that "the likes of it wouldn't be heard in Russia!" It's hard now to sing The Galway Races without the image of Mrs. O'Connell flitting across my mind's eye. This version was recorded live in O'Flaherty's Irish Pub, New Orleans.

Danny Dougan believed life was for living and the spending of your children's inheritance. "Let them get their own" was his philosophy, and it's mine also. And what better way to spend it than by buying a dozen of these CDs as presents for your friends? Indeed this recording would make a lovely present for someone you're not that crazy about (and the royalties would help to pay for my mother's operation). I'm joined by my sister Geraldine on this comic song, Danny Dougan's Jubilee. Geraldine is one of Australia's top stand-up comedians. It's another tune we learned from Jimmy O'Dea.

In Ireland our ancient fatalism has been spurned by a new generation of dynamic young men and women. The racial memory has well and truly awakened from its usual state of slumbering inferiority to find a country now infused with pride and self-reliance, evidenced in the bustling joy of life and riot of colour that is modern Irish life. Pete St. John's anthemic Spirit of the Gael speaks eloquently to these exciting new times.

Ireland, Oh, Ireland.

Our Nation will prevail

Forever free through all eternity

Lives the Spirit of the Gael.

Danny Doyle