|

|

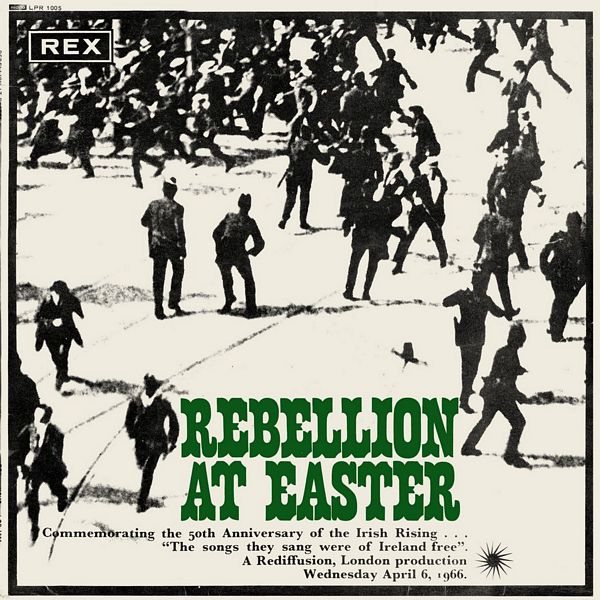

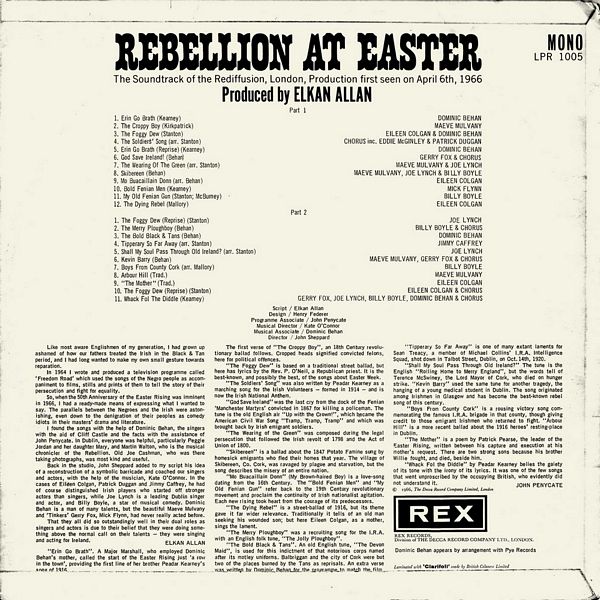

Sleeve Notes

Like most aware Englishmen of my generation, I had grown up ashamed of how our fathers treated the Irish in the Black & Tan period, and I had long wanted to make my own small gesture towards reparation. In 1964

I wrote and produced a television programme called 'Freedom Road' which used the songs of the Negro people as accompaniment to films, stills and prints of them to tell the story of their persecution and fight for equality.

So, when the 50th Anniversary of the Easter Rising was imminent in 1966, I had a ready-made means of expressing what I wanted to say. The parallels between the Negroes and the Irish were astonishing, even down to the denigration of their peoples as comedy idiots in their masters' drama and literature.

I found the songs with the help of Dominic Behan, the singers with the aid of Cliff Castle and the facts with the assistance of John Penycate. In Dublin, everyone was helpful, particularly Peggie Jordan and her daughter Mary, and Martin Walton, who is the musical chronicler of the Rebellion. Old Joe Cashman, who was there taking photographs, was most kind and useful.

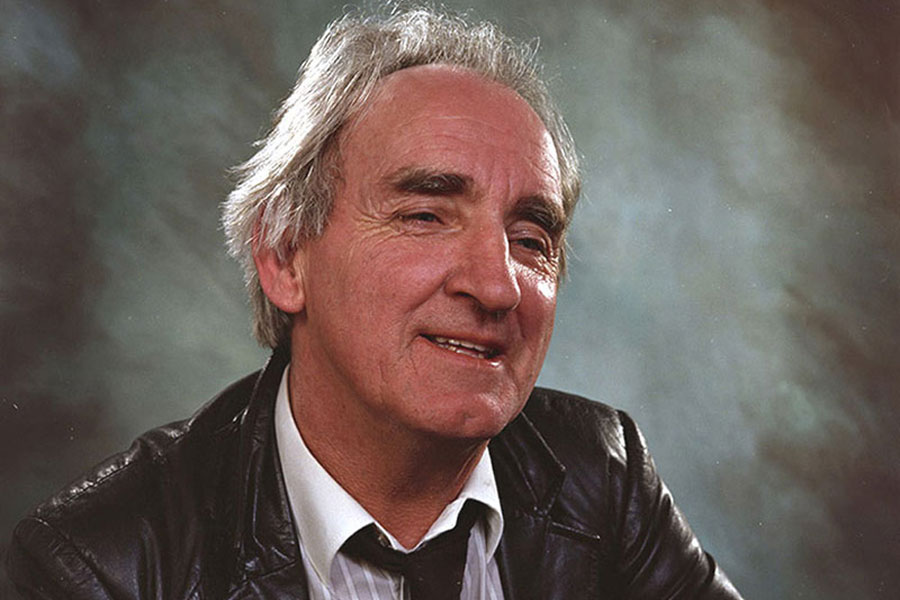

Back in the studio, John Sheppard added to my script his idea of a reconstruction of a symbolic barricade and coached our singers and actors, with the help of the musician, Kate O'Connor. In the cases of Eileen Colgan, Patrick Duggan and Jimmy Caffrey, he had of course distinguished Irish players who started off stronger actors than singers, while Joe Lynch is a leading Dublin singer and actor, and Billy Boyle, a star of musical comedy. Dominic Behan is a man of many talents, but the beautiful Maeve Mulvany and 'Tinkers' Gerry Fox, Mick Flynn, had never really acted before.

That they all did so outstandingly well in their dual roles as singers and actors is due to their belief that they were doing something above the normal call on their talents — they were singing and acting for Ireland.

ELKAN ALLAN

"Erin Go Brath". A Major Marshall, who employed Dominic Behan's mother, called the start of the Easter Rising just 'a row in the town', providing the first line of her brother Peadar Kearney's song of 1916.

The first verse of "The Croppy Boy", an 18th Century revolutionary ballad follows. Cropped heads signified convicted felons, here for political offences.

"The Foggy Dew" is based on a traditional street ballad, but here has lyrics by the Rev. P. O'Neil, a Republican priest. It is the best-known, and possibly the best, of the songs about Easter Week.

"The Soldiers' Song" was also written by Peadar Kearney as a marching song for the Irish Volunteers — formed in 1914 — and is now the Irish National Anthem.

"God Save Ireland" was the last cry from the dock of the Fenian 'Manchester Martyrs' convicted in 1867 for killing a policeman. The tune is the old English air "Up with the Crown!", which became the American Civil War Song "Tramp, Tramp, Tramp" and which was brought back by Irish emigrant soldiers.

"The Wearing of the Green" was composed during the legal persecution that followed the Irish revolt of 1798 and the Act of Union of 1800.

"Skibereen" is a ballad about the 1847 Potato Famine sung by homesick emigrants who fled their homes that year. The village of Skibereen, Co. Cork, was ravaged by plague and starvation, but the song describes the misery of an entire nation.

"Mo Buacaillain Donn" (My Brown-haired Boy) is a love-song dating from the 16th Century. The "Bold Fenian Men" and "My Old Fenian Gun" refer back to the 19th Century revolutionary movement and proclaim the continuity of Irish nationalist agitation. Each new rising took heart from the courage of its predecessors.

"The Dying Rebel" is a street-ballad of 1916, but its theme gave it far wider relevance. Traditionally it tells of an old man seeking his wounded son; but here Eileen Colgan, as a mother, sings the lament.

"The Merry Ploughboy" was a recruiting song for the I.R.A. with an English folk tune, "The Jolly Ploughboy".

"The Bold Black & Tans". An old English tune, "The Devon Maid", is used for this indictment of that notorious corps named after its motley uniforms. Balbriggan and the city of Cork were but two of the places burned by the Tans as reprisals. An extra verse was written by Dominic Behan for the programme to match the film

"Tipperary So Far Away" is one of many extant laments for Seán Treacy, a member of Michael Collins' I.R.A. Intelligence Squad, shot down in Talbot Street, Dublin, on Oct. 14th, 1920.

"Shall My Soul Pass Through Old Ireland?" The tune is the English "Rolling Home to Merry England", but the words tell of Terence McSwiney, the Lord Mayor of Cork, who died on hunger strike. "Kevin Barry" used the same tune for another tragedy, the hanging of a young medical student in Dublin. The song originated among Irishmen in Glasgow and has become the best-known rebel song of this century.

"Boys From County Cork" is a rousing victory song commemorating the famous I.R.A. brigade in that county, though giving credit to those emigrant Irishmen who returned to fight. "Arbour Hill" is a more recent ballad about the 1916 heroes' resting-place in Dublin.

"The Mother" is a poem by Patrick Pearse, the leader of the Easter Rising, written between his capture and execution at his mother's request. There are two strong sons because his brother Willie fought, and died, beside him.

"Whack Fol the Diddle" by Peadar Kearney belies the gaiety of its tone with the irony of its lyrics. It was one of the few songs that went unproscribed by the occupying British, who evidently did not understand it.

JOHN PENYCATE

©1966, The Decca Record Company Limited, London

Notes

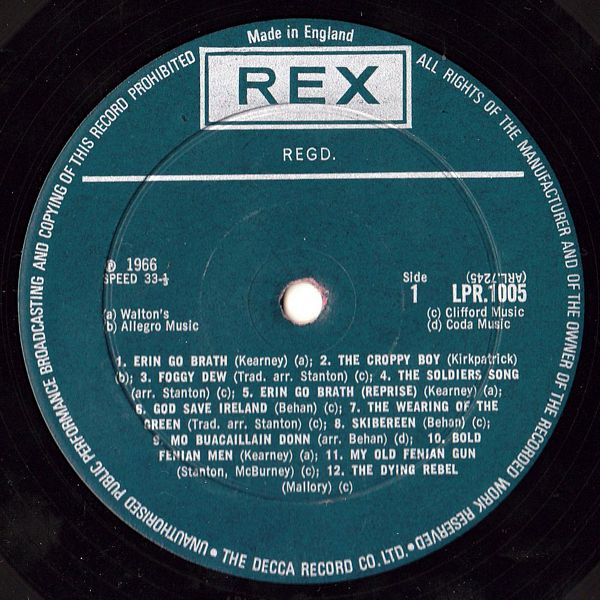

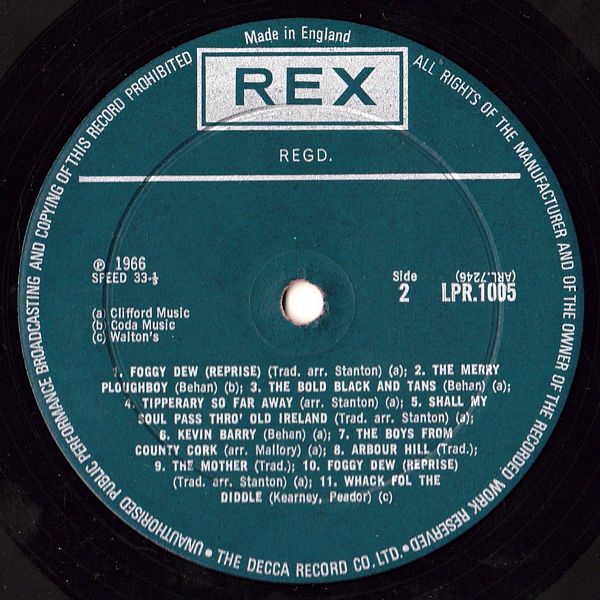

This the soundtrack from 1966 TV documentary Rebellion At Easter: The Songs They Sang Were Of Ireland Free — Commemoration of the 50th Anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin, using songs of the time as commentary. Singers include

Dominic Behan, Billy Boyle, James Caffrey, Eileen Colgan, Jerry Fox, Joe Lynch, Maeve Mulvanny, Michael Flynn, Eddie McGinley, and Patrick Duggan.

On Easter Monday, 1916, a tiny but determined army sized five key buildings in Dublin. Their stories and the events that followed are told through the songs they sang and the films and photographs of the time.

Source: Irish Film & TV Research Online - Trinity College Dublin