|

|

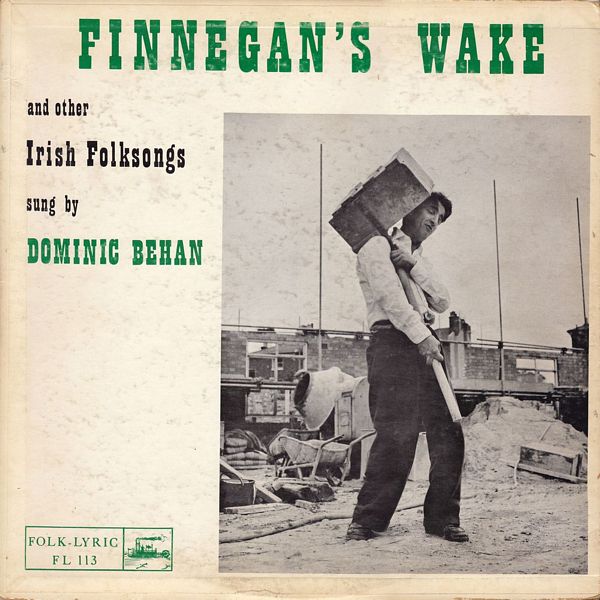

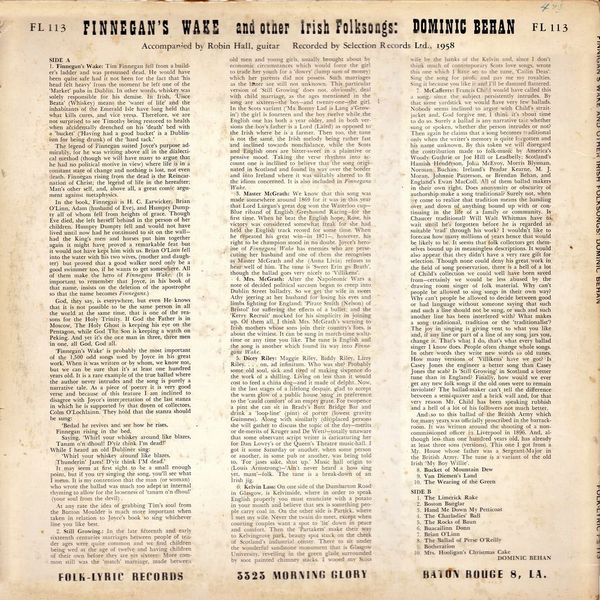

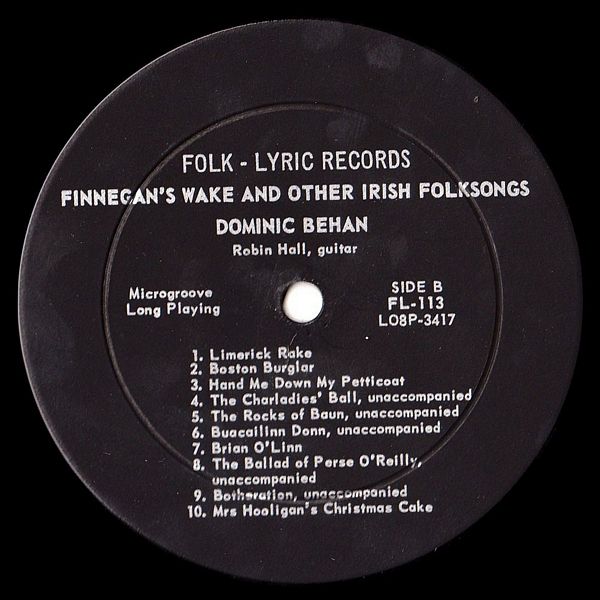

Sleeve Notes

Finnegan's Wake: Tim Finnegan fell from a builder's ladder and was presumed dead. He would have been quite safe had it not been for the fact that 'his head felt heavy' from the moment he left one of the 'Market' pubs in Dublin. In other words, whiskey was solely responsible for his demise. In Irish, 'Uisce Beata' (Whiskey) means the 'water of life' and the inhabitants of the Emerald Isle have long held that what kills cures, and vice versa. Therefore, we are not surprised to see Timothy being restored to health when accidentally drenched on his 'death' bed with a 'bucket' ('Having had a good bucket' is a Dublinism for being drunk) of the 'hard tack.'

The legend of Finnegan suited Joyce's purpose admirably, for he was writing above all in the dialectical method (though we will have many to argue that he had no political motive in view) where life is in a constant state of change and nothing is lost, not even death. Finnegan rising from the dead is the Reincarnation of Christ; the legend of life in the hereafter; Man's other self, and, above all, a great comic argument against metaphysics.

In the book, Finnegan is H. C. Earwicker, Brian O'Linn, Adam (husband of Eve), and Humpty Dumpty all of whom fell from heights of grace. Though Eve died, she left herself behind in the person of her children. Humpty Dumpty fell and would not have lived until now had he continued to sit on the wall — had the King's men and horses put him together again it might have proved a remarkable feat but it would not have kept him with us. Brian O'Linn fell into the water with his two wives, (mother and daughter) but proved that a good walker need only be a good swimmer too, if he wants to get somewhere. All of them make the hero of Finnegans Wake. (It is important to remember that Joyce, in his book of that name, insists on the deletion of the apostrophe so that the name becomes Finnegans.)

God, they say, is everywhere, but even He knows that it is not possible to be the same person in all the world at the same time, that is one of the reasons for the Holy Trinity. If God the Father is in Moscow, The Holy Ghost is keeping his eye on the, Pentagon, while God The Son is keeping a watch on Peking. And yet it's the one man in three, three men in one, all God, God all.

'Finnegan's Wake' is probably the most important of the 1,500 odd songs used by Joyce in his great work. When it was written or by whom, we know not, but we can be sure that it's at least one hundred years old. It is a rare example of the true ballad where the author never intrudes and the song is purely a narrative tale. As a piece of poetry it is very good verse and because of this feature I am inclined to disagree with Joyce's interpretation of the last stanza in which he is supported by that doyen of collectors, Colm O'Lochlainn. They hold that the stanza should be sung:

'Bedad he revives and see how he rises,

Finnegan rising in the bed,

Saying, 'Whirl your whiskey around like blazes,

Tanam o'n dhoul! D'yiz think I'm dead!'

While I heard an old Dubliner sing:

'Whirl your whiskey around like blazes,

Thunderin' Jazes! D'yiz think I'M dead.'

It may seem at first sight to be a small enough point, but if you try singing the song, you'll see what I mean. It is my contention that the man (or woman) who wrote the ballad was much too adept at internal rhyming to allow for the looseness of 'tanam o'n dhoul' (your soul from the devil).

At any rate the idea of grabbing Tim's soul from the Button Moulder is much more important when taken in relation to Joyce's book so sing whichever line you like best.

Still Growing.: In the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries marriages between people of tender ages were quite common and we find children being wed at the age of twelve and having children of their own before they are vet sixteen More common still was the 'match' marriage. made between old men and young girls, usually brought about by economic circumstances which would force the girl to trade her youth for a 'dowry' (lump sum of money) which her parents did not possess. Such marriages as the latter are still not unknown. This particular version of 'Still Growing' does not, obviously, deal with child marriage, as the ages mentioned in the song are sixteen — the boy — and twenty-one — the girl. In the Scots variant ('Ma Bonny Lad is Lang a'Grow-in') the girl is fourteen and the boy twelve while the English one has both a year older, and in both versions the boy's father is a Lord (Laird) as opposed to the Irish where he is a farmer. Then too, the tune is not the same, the Irish melody being rather fast and inclined towards nonchalance, while the Scots and English ones are bitter-sweet in a plaintive or pensive mood. Taking the verse rhythms into account one is inclined to believe that the song originated in Scotland and found its way over the border and into Ireland where it was suitably altered to fit the idiom concerned. It is also included in Finnegans Wake.

Master McGrath: We know that this song was made somewhere around 1869 for it was in this year that Lord Lurgan's great dog won the Waterloo cup — Blue riband of English Greyhound Racing — for the first time. When he beat the English hope. Rose, his victory was considered somewhat freak for she had held the English track record for some time. When he repeated his great win — in 1871 —, however, his right to be champion stood in no doubt. Joyce's heroine of Finnegans Wake has enemies who are persecuting her husband and one of them she recognises as Master McGrath and she (Anna Livia) refuses to hear well of him. The tune is 'Sweet Erin go Brath', though the ballad goes very nicely to 'Villikens'.

Mrs. McGrath: After the Napoleonic Wars a note of decided political sarcasm began to creep into Dublin Street balladry. So we get the wife in sweet Athy jeering at her husband for losing his eyes and limbs fighting for England; 'Pirate Smith (Nelson) of Bristol' for suffering the effects of a bullet: and the 'Kerry Recruit' mocked for his simplicity in joining up. Of them all, I think Mrs. McGrath's warning to Irish mothers whose sons join their country's foes, is about the wittiest. It can be sung in march-time waltz-time or any time you like. The tune is English and the song is another which found its way into Finnegans Wake.

Dicey Riley: Maggie Riley, Biddy Riley, Lizzy Riley. . . .on, ad infinitum. Who was she? Probably some old soul, sick and tired of making sixpence do the work of a shilling. Living on less than it would cost to feed a china dog — and it made of delpht. Now, in the last stages of a lifelong despair, glad to accept the warm glow of a public house 'snug' in preference to the 'cauld comfort' of an empty grate. For twopence a pint she can sit in Brady's Butt Bridge Bar and drink a 'loop-line' (pint) of porter (lowest gravity Guinness). Along with similarly (dis)placed persons she will gather to discuss the topic of the day — merits or de-merits of Kruger and De Wett? — totally unaware that some observant script writer is caricaturing her for Dan Lowry's or the Queen's Theatre music-hall. I got it some Saturday or another, when some person or another, in some pub or another, was being told to, 'For jases sake, shut up.' Music hall origin to (Louis Armstrong) — 'Ain't never heard a hoss sing yet, mam' — folk. The tune is a break-down of an Irish jig.

Kelvin Lass: On one side of the Dumbarton Road in Glasgow, is Kelvinside, where in order to speak English properly you must enunciate with a potato in your mouth and believe that sex is something people carry coal in. On the other side is Partick, where I met my wife. Never the twain do meet, except when courting couples want a spot to 'lie' down in peace and comfort. Then the 'Partakers' make their way to Kelvingrove park, beauty spot stuck on the cheek. of Scotland's industrial center. There to sit under the wonderful sandstone monument that is Glasgow University., revelling in the green glade surrounded bv soot painted ch.im.nev stacks. I wooed my Scots wife by the banks of the Kelvin and, since I don't think much of contemporary Scots love songs, wrote this one which I have set to the tune, 'Cailin Deas': Sing the song for profit and pay me my royalties. Sing it because you like it and I'll be damned flattered.

McCafferty: Francis Child would have called this a song, since the subject persistently intrudes. By that same yardstick we would have very few ballads. Nobody seems inclined to argue with Child's strait-jacket and, God forgive me, I think it's about time to do so. Surely a ballad is any narrative tale whether sung or spoken, whether the person intrudes or not? Then again he claims that a song becomes traditional only when the writer's memory is quite forgotten and his name unknown. By this token we will disregard the contribution made to folk-music by America's Woody Guthrie or Joe Hill or Leadbelly; Scotland's Hamish Henderson, John McEvoy, Morris Blysman, Norman Buchan; Ireland's Peadar Kearne, M. J. Moran, Johnnie Patterson, or Brendan Behan, and England's Ewan MacColl. All of them ballad makers in their own right. Does anonymity or obscurity of authorship make a song traditional? Surely not, when we come to realize that tradition means the handing over and down of anything bound up with or continuing in the life of a family or community.. Is Chaucer traditional? Will Walt Whitman have to wait until he's forgotten before he is regarded as suitable 'trad' through his work? I wouldn't like to forecast how many millions of years hence that would be likely to be. It seems that folk collectors get themselves bound up in meaningless descriptions. It would also appear that they didn't have a very rare gift for selection. Though none could deny his great work in. the field of song preservation, there is a hell of a lot of Child's collection we could well have been sayed from — certainly we would be less abused by the drawing room singer of folk material. Why can't people be allowed to sing songs in their own way? Why can't people be allowed to decide between good or bad language without someone saying that such and such a line should not be sung, or such and such another line has been interfered' with? What makes a song traditional, tradition or the 'traditionalist'? The joy in singing is giving vent to what you like and, if any line or part of a line of any song jars you, change it. That's what I do, that's what every ballad singer I know does. People often change whole songs. In other words they write new words to old tunes. How many versions of 'Villikens' have we got? Is Casey Jones the engineer a better song than^ Casey Jones the scab? Is 'Still Growing' in Scotland a better tune than in England? Finally, how would we ever get any new folk songs if the old ones were to remain inviolate? The ballad-maker can't tell the difference between a semi-quaver and a brick wall and, for that very reason Mr. Child has been speaking rubbish and a hell of a lot of his followers not much better.

And so to this ballad of the British Army which for many years was officially proscribed in the barrack-room. It was written around the shooting of a noncommissioned officer m Liverpool in 1896. And, although less than one hundred years old, has already at least three sons (versions). This one I got from a Mr. House whose father was a Sergeant-Major in the British Army. The tune is a variant of the old Irish 'My Boy Willie'.

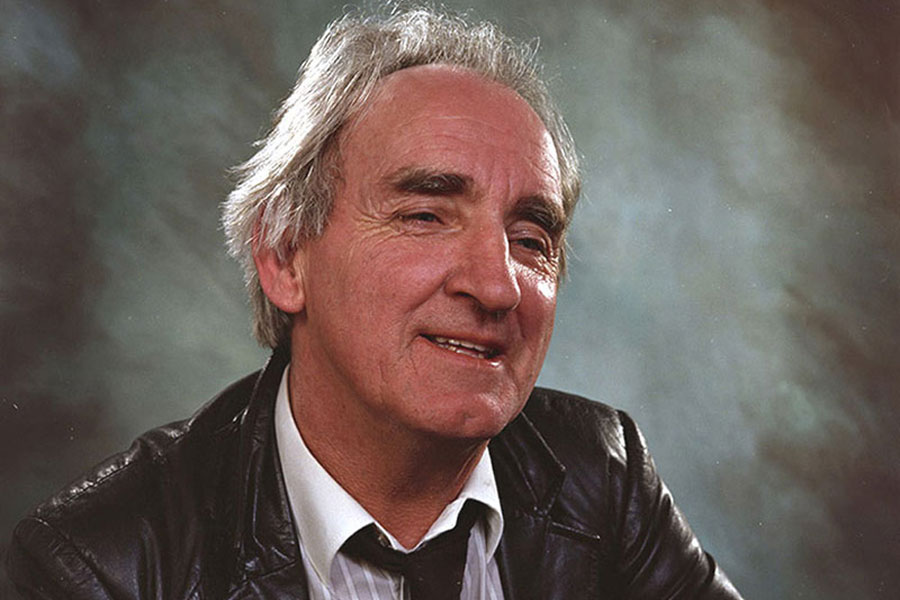

DOMINIC BEHAN