|

|

|

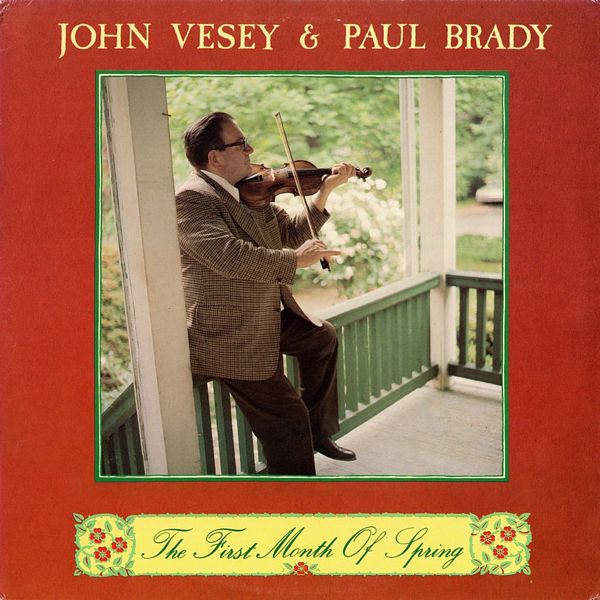

Sleeve Notes

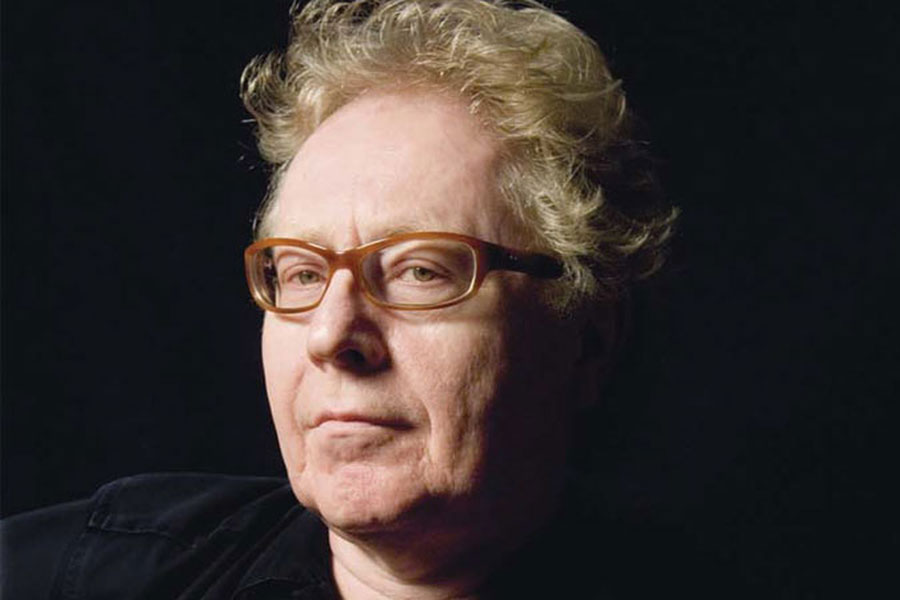

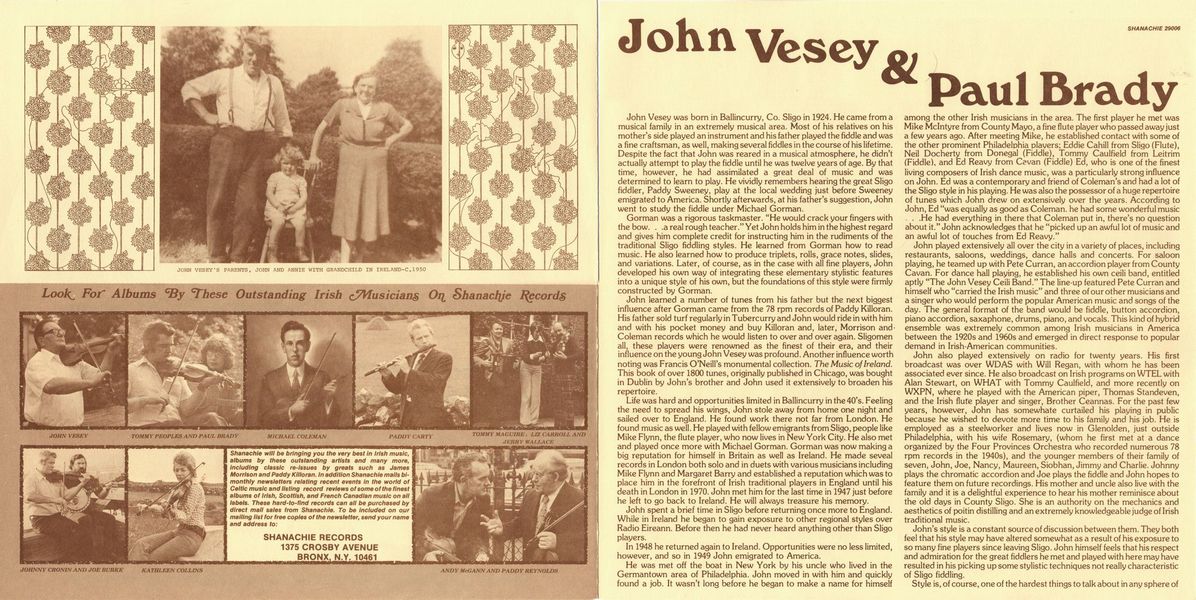

John Vesey was born in Ballincurry, Co. Sligo in 1924. He came from a musical family in an extremely musical area. Most of his relatives on his mother's side played an instrument and his father played the fiddle and was a fine craftsman, as well, making several fiddles in the course of his lifetime. Despite the fact that John was reared in a musical atmosphere, he didn't actually attempt to play the fiddle until he was twelve years of age. By that time, however, he had assimilated a great deal of music and was determined to learn to play. He vividly remembers hearing the great Sligo fiddler, Paddy Sweeney, play at the local wedding just before Sweeney emigrated to America. Shortly afterwards, at his father's suggestion, John went to study the fiddle under Michael Gorman.

Gorman was a rigorous taskmaster. "He would crack your fingers with the bow … a real rough teacher." Yet John holds him in the highest regard and gives him complete credit for instructing him in the rudiments of the traditional Sligo fiddling styles. He learned from Gorman how to read music. He also learned how to produce triplets, rolls, grace notes, slides, and variations. Later, of course, as in the case with all fine players, John developed his own way of integrating these elementary stylistic features into a unique style of his own, but the foundations of this style were firmly constructed by Gorman.

John learned a number of tunes from his father but the next biggest influence after Gorman came from the 78 rpm records of Paddy Killoran. His father sold turf regularly in Tubercurry and John would ride in with him and with his pocket money and buy Killoran and, later, Morrison and Coleman records which he would listen to over and over again. Sligomen all, these players were renowned as the finest of their era, and their influence on the young John Vesey was profound. Another influence worth noting was Francis O'Neill's monumental collection. The Music of Ireland. This book of over 1800 tunes, originally published in Chicago, was bought in Dublin by John's brother and John used it extensively to broaden his repertoire.

Life was hard and opportunities limited in Ballincurry in the 40's. Feeling the need to spread his wings, John stole away from home one night and sailed over to England. He found work there not far from London. He found music as well. He played with fellow emigrants from Sligo, people like Mike Flynn, the flute player, who now lives in New York City. He also met and played once more with Michael Gorman. Gorman was now making a big reputation for himself in Britain as well as Ireland. He made several records in London both solo and in duets with various musicians including Mike Flynn and Margaret Barry and established a reputation which was to place him in the forefront of Irish traditional players in England until his death in London in 1970. John met him for the last time in 1947 just before he left to go back to Ireland. He will always treasure his memory.

John spent a brief time in Sligo before returning once more to England. While in Ireland he began to gain exposure to other regional styles over Radio Eireann. Before then he had never heard anything other than Sligo players.

In 1948 he returned again to Ireland. Opportunities were no less limited, however, and so in 1949 John emigrated to America.

He was met off the boat in New York by his uncle who lived in the Germantown area of Philadelphia. John moved in with him and quickly found a job. It wasn't long before he began to make a name for himself among the other Irish musicians in the area. The first player he met was Mike McIntyre from County Mayo, a fine flute player who passed away just a few years ago. After meeting Mike, he established contact with some of the other prominent Philadelphia players; Eddie Cahill from Sligo (Flute), Neil Docherty from Donegal (Fiddle), Tommy Caulfield from Leitrim (Fiddle), and Ed Reavy from Cavan (Fiddle) Ed, who is one of the finest living composers of Irish dance music, was a particularly strong influence on John. Ed was a contemporary and friend of Coleman's and had a lot of the Sligo style in his playing. He was also the possessor of a huge repertoire of tunes which John drew on extensively over the years. According to John, Ed "was equally as good as Coleman, he had some wonderful music … He had everything in there that Coleman put in, there's no question about it." John acknowledges that he "picked up an awful lot of music and an awful lot of touches from Ed Reavy."

John played extensively all over the city in a variety of places, including restaurants, saloons, weddings, dance halls and concerts. For saloon playing, he teamed up with Pete Curran, an accordion player from County Cavan. For dance hall playing, he established his own ceili band, entitled aptly "The John Vesey Ceili Band." The line-up featured Pete Curran and himself who "carried the Irish music" and three of our other musicians and a singer who would perform the popular American music and songs of the day. The general format of the band would be fiddle, button accordion, piano accordion, saxaphone, drums, piano, and vocals. This kind of hybrid ensemble was extremely common among Irish musicians in America between the 1920s and 1960s and emerged in direct response to popular demand in Irish-American communities.

John also played extensively on radio for twenty years. His first broadcast was over WDAS with Will Regan, with whom he has been associated ever since. He also broadcast on Irish programs on WTEL with Alan Stewart, on WHAT with Tommy Caulfield, and more recently on WXPN, where he played with the American piper, Thomas Standeven, and the Irish flute player and singer, Brother Ceannas. For the past few years, however, John has somewhat curtailed his playing in public because he wished to devote more time to his family and his job. He is employed as a steelworker and lives now in Glenolden, just outside Philadelphia, with his wife Rosemary, (whom he first met at a dance organized by the Four Provinces Orchestra who recorded numerous 78 rpm records in the 1940s), and the younger members of their family of seven, John, Joe, Nancy, Maureen, Siobhan, Jimmy and Charlie. Johnny plays the chromatic accordion and Joe plays the fiddle and John hopes to feature them on future recordings. His mother and uncle also live with the family and it is a delightful experience to hear his mother reminisce about the old days in County Sligo. She is an authority on the mechanics and aesthetics of poitin distilling and an extremely knowledgeable judge of Irish traditional music.

John's style is a constant source of discussion between them. They both feel that his style may have altered somewhat as a result of his exposure to so many fine players since leaving Sligo. John himself feels that his respect and admiration for the great fiddlers he met and played with here may have resulted in his picking up some stylistic techniques not really characteristic of Sligo fiddling.

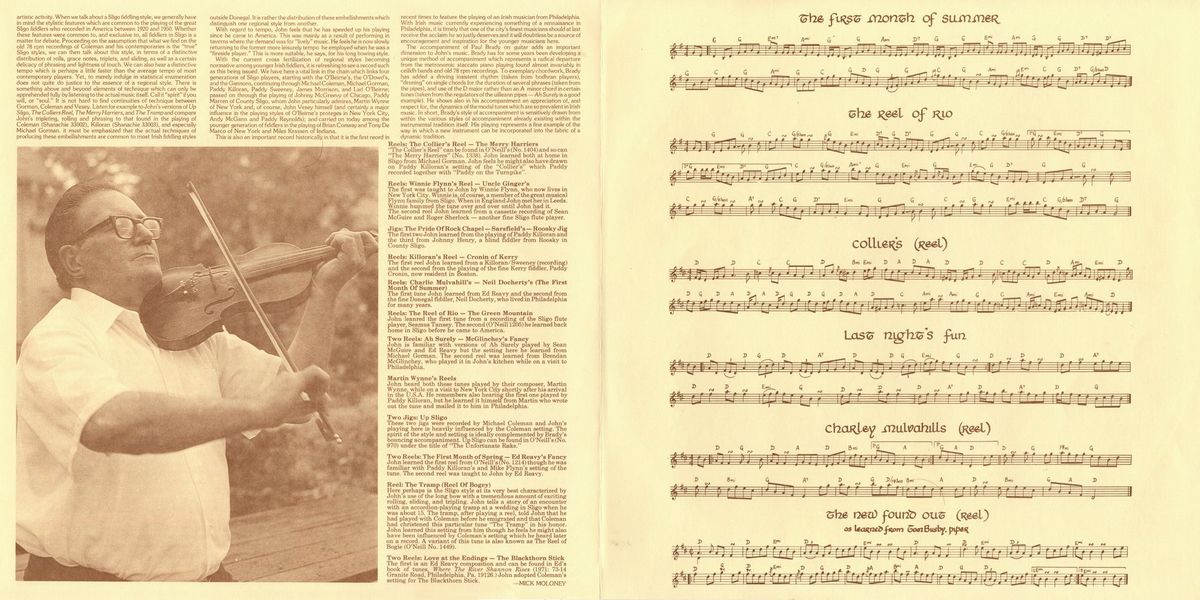

Style is, of course, one of the hardest things to talk about in any sphere of artistic activity. When we talk about a Sligo fiddling style, we generally have in mind the stylistic features which are common to the playing of the great Sligo fiddlers who recorded in America between 1920 and 1950. Whether these features were common to, and exclusive to, all fiddlers in Sligo is a matter for debate. Proceeding on the assumption that what we find on the old 78 rpm recordings of Coleman and his contemporaries is the "true" Sligo styles, we can then talk about this style, in terms of a distinctive distribution of rolls, grace notes, triplets, and sliding, as well as a certain delicacy of phrasing and lightness of touch. We can also hear a distinctive tempo which is perhaps a little faster than the average tempo of most contemporary players. Yet, to merely indulge in statistical enumeration does not quite do justice to the essence of a regional style. There is something above and beyond elements of technique which can only be apprehended fully by listening to the actual music itself. Call it "spirit" if you will, or "soul." It is not hard to find continuities of technique between Gorman, Coleman and Vesey. Listen for example to John's versions of Up Sligo, The Colliers Reel, The Merry Harriers, and The Tramp and compare John's tripleting, rolling and phrasing to that found in the playing of Coleman (Shanachie 33002), Killoran (Shanachie 33003), and especially Michael Gorman, it must be emphasized that the actual techniques of producing these embellishments are common to most Irish fiddling styles outside Donegal. It is rather the distribution of these embellishments which distinguish one regional style from another.

With regard to tempo, John feels that he has speeded up his playing since he came to America. This was mainly as a result of performing in taverns where the demand was for "lively" music. He feels he is now slowly returning to the former more leisurely tempo he employed when he was a "fireside player." This is more suitable, he says, for his long bowing style.

With the current cross fertilization of regional styles becoming normative among younger Irish fiddlers, it is refreshing to see a record such as this being issued. We have here a vital link in the chain which links four generations of Sligo players, starting with the O'Beirne's, the O'Dowd's, and the Gannons, continuing through Michael Coleman, Michael Gorman, Paddy Killoran, Paddy Sweeney, James Morrison, and Lad O'Beirne; passed on through the playing of Johnny McGreevy of Chicago, Paddy Marren of County Sligo, whom John particularly admires, Martin Wynne of New York and, of course, John Vesey himself (and certainly a major influence in the playing styles of O'Beirne's proteges in New York City, Andy McGann and Paddy Reynolds); and carried on today among the younger generation of fiddlers in the playing of Brian Conway and Tony De Marco of New York and Miles Krassen of Indiana.

This is also an important record historically in that it is the first record in recent times to feature the playing of an Irish musician from Philadelphia. With Irish music currently experiencing something of a renaissance in Philadelphia, it is timely that one of the city's finest musicians should at last receive the acclaim he so justly deserves and it will doubtless be a source of encouragement and inspiration for the younger musicians here.

The accompaniment of Paul Brady on guitar adds an important dimension to John's music. Brady has for some years been developing a unique method of accompaniment which represents a radical departure from the metronomic staccato piano playing found almost invariably in ceilidh bands and old 78 rpm recordings. To exemplary chordwork, Brady has added a driving insistent rhythm (taken from bodhran players), "droning" on single chords for the duration of several phrases (taken from the pipes), and use of the D major rather than an A minor chord in certain tunes (taken from the regulators of the uilleann pipes — Ah Surely is a good example). He shows also in his accompaniment an appreciation of, and respect for, the dynamics of the modal tunes which are so prevalent in Irish music. In short, Brady's style of accompaniment is sensitively drawn from within the various styles of accompaniment already existing within the instrumental tradition itself. His playing represents a fine example of the way in which a new instrument can be incorporated into the fabric of a dynamic tradition.

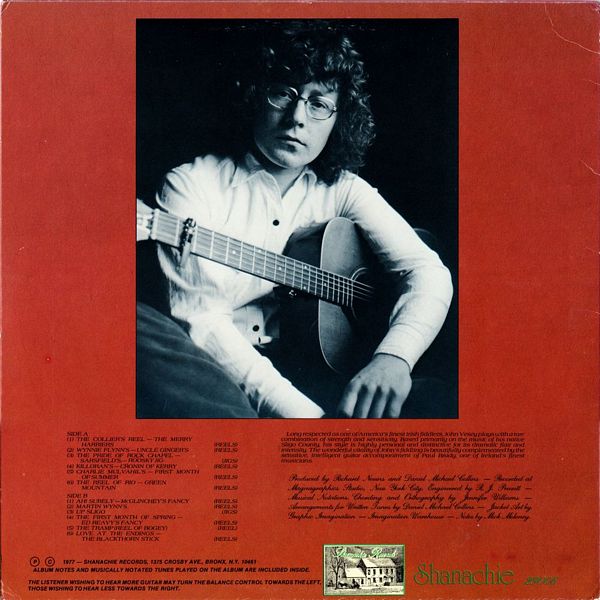

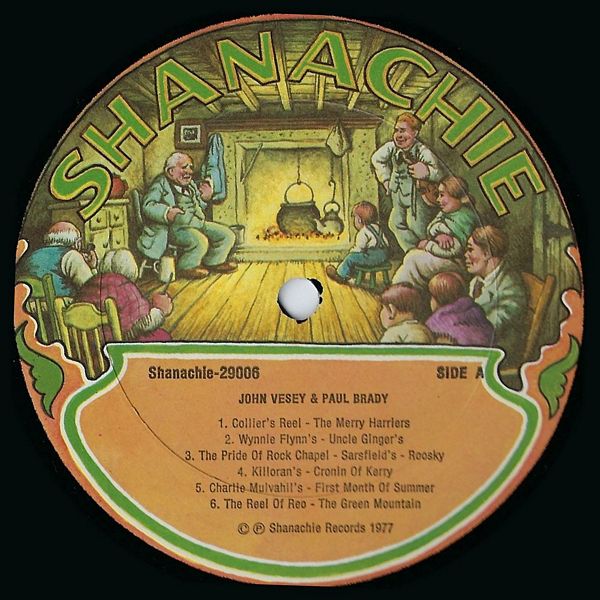

Reels: The Collier's Reel — The Merry Harriers

"The Collier's Reel" can be found in O'Neill's (No. 1404) and so can "The Merry Harriers" (No. 1338). John learned both at home in Sligo from Michael Gorman. John feels he might also have drawn on Paddy Killoran's setting of the "Collier's" which Paddy recorded together with "Paddy on the Turnpike".

Reels: Winnie Flynn's Reel — Uncle Ginger's

The first was taught to John by Winnie Flynn, who now lives in New York City. Winnie is, of course, a member of the great musical Flynn family from Sligo. When in England John met her in Leeds. Winnie hummed the tune over and over until John had it.

The second reel John learned from a cassette recording of Sean McGuire and Roger Sherlock — another fine Sligo flute player.

Jigs: The Pride Of Rock Chapel — Sarsfield's — Roosky Jig

The first two John learned from the playing of Paddy Killoran and the third from Johnny Henry, a blind fiddler from Roosky in County Sligo.

Reels: Killoran's Reel — Cronin of Kerry

The first reel John learned from a Killoran/Sweeney (recording) and the second from the playing of the fine Kerry fiddler, Paddy Cronin, now resident in Boston.

Reels: Charlie Mulvahill's — Neil Docherty's (The First Month Of Summer)

The first tune John learned from Ed Reavy and the second from the fine Donegal fiddler, Neil Docherty, who lived in Philadelphia for many years.

Reels: The Reel of Rio — The Green Mountain

John learned the first tune from a recording of the Sligo flute player, Seamus Tansey. The second (O'Neill 1205) he learned back home in Sligo before he came to America.

Two Reels: Ah Surely — McGlinchey's Fancy

John is familiar with versions of Ah Surely played by Sean McGuire and Ed Reavy but the setting here he learned from Michael Gorman. The second reel was learned from Brendan McGlinchey, who played it in John's kitchen while on a visit to Philadelphia.

Martin Wynne's Reels

John heard both these tunes played by their composer, Martin Wynne, while on a visit to New York City shortly after his arrival in the U.S.A. He remembers also hearing the first one played by Paddy Killoran, but he learned it himself from Martin who wrote out the tune and mailed it to him in Philadelphia.

Two Jigs: Up Sligo

These two jigs were recorded by Michael Coleman and John's playing here is heavily influenced by the Coleman setting. The spirit of the style and setting is ideally complemented by Brady's bouncing accompaniment. Up Sligo can be found in O'Neill's (No. 970) under the title of "The Unfortunate Rake."