|

|

|

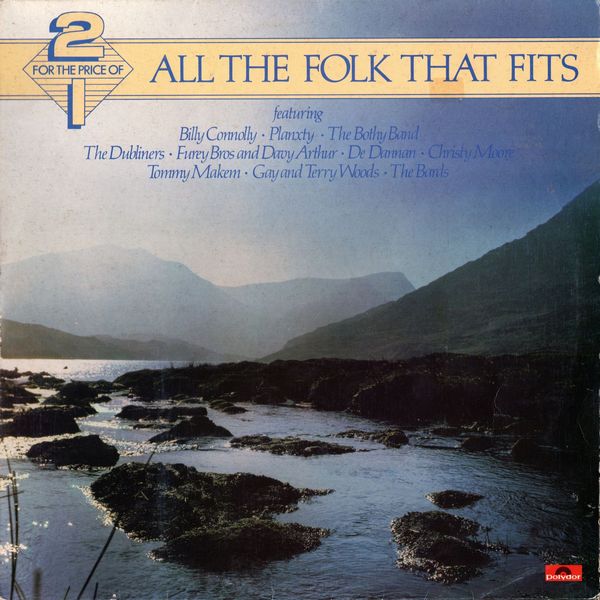

Sleeve Notes

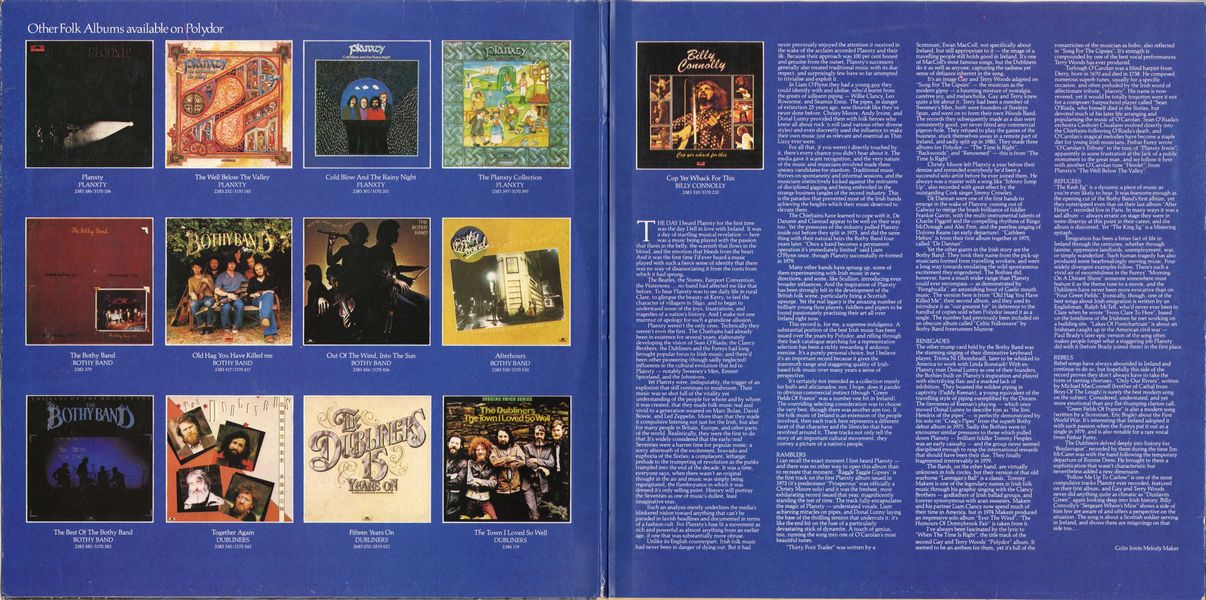

The Day I heard Planxty for the first time was the day I fell in love with Ireland. It was a day of startling musical revelation — here was a music being played with the passion that flares in the belly, the warmth that flows in the blood, and the emotion that bleeds from the heart. And it was the first time I'd ever heard a music played with such a fierce sense of identity that there was no way of disassociating it from the roots from which it had sprung.

The Beatles, the Stones, Fairport Convention, the Watersons … no band had affected me like that before. To hear Planxty was to see daily life in rural Clare, to glimpse the beauty of Kerry, to feel the character of villagers in Sligo, and to begin to understand some of the joys, frustrations, and tragedies of a nation's history. And I make not one murmur of apology for such a grandiose allusion.

Planxty weren't the only ones. Technically they weren't even the first. The Chieftains had already been in existence for several years, elaborately developing the vision of Seán O'Riada; the Clancy Brothers, the Dubliners and the Fureys had long brought popular focus to Irish music; and there'd been other pioneering (though sadly neglected) influences in the cultural evolution that led to Planxty — notably Sweeney's Men, Emmet Spiceland, and the Johnstons.

Yet Planxty were, indisputably, the trigger of an explosion that still continues to mushroom. Their music was so shot full of the vitality yet understanding of the people for whom and by whom it was created, that they made folk music real and vivid to a generation weaned on Marc Bolan, David Bowie, and Led Zeppelin. More than that they made it compulsive listening not just for the Irish, but also for many people in Britain, Europe, and other parts of the world. Realistically, they were the first to do that. It's widely considered that the early/mid Seventies were a barren time for popular music: a sorry aftermath of the excitement, bravado and euphoria of the Sixties; a complacent, lethargic prelude to the trumpeting of revolution as the punks trampled into the end of the decade. It was a time, everyone says, when there wasn't an original thought in the air and music was simply being regurgitated, the flamboyance in which it was dressed it's only selling point. History will portray the Seventies as one of music's dullest, least imaginative eras.

Such an analysis merely underlines the media's blinkered vision toward anything that can't be paraded in lavish headlines and documented in terms of a fashion cult. For Planxty's fuse lit a movement as rich and powerful as almost anything from an earlier age, if one that was substantially more obtuse.

Unlike its English counterpart, Irish folk music had never been in danger of dying out. But it had never previously enjoyed the attention it received in the wake of the acclaim accorded Planxty and their ilk. Because their approach was 100 per cent honest and genuine from the outset, Planxty's successors generally also treated traditional music with its due respect, and surprisingly few have so far attempted to trivialise and exploit it.

In Liam O'Flynn they had a young guy they could identify with and idolise, who'd learnt from the greats of uilleann piping — Willie Clancy, Leo Rowsome, and Seamus Ennis. The pipes, in danger of extinction 25 years ago, now flourish like they've never done before. Christy Moore, Andy Irvine, and Dónal Lunny provided them with folk heroes who knew all about rock 'n roll (and various other diverse styles) and even discreetly used the influence to make their own music just as relevant and essential as Thin Lizzy ever were.

For all that, if you weren't directly touched by it, there's every chance you didn't hear about it. The media gave it scant recognition, and the very nature of the music and musicians involved made them uneasy candidates for stardom. Traditional music thrives on spontaneity and informal sessions, and the musicians instinctively kicked against the restraints of disciplined gigging and being embroiled in the strange business tangles of the record industry. This is the paradox that prevented most of the Irish bands achieving the heights which their music deserved to elevate them.

The Chieftains have learned to cope with it, De Danann and Clannad appear to be well on their way too. Yet the pressures of the industry pulled Planxty inside out before they split in 1975, and did the same thing with their natural heirs the Bothy Band four years later. "Once a band becomes a permanent operation it's immediately limited" said Liam O'Flynn once, though Planxty successfully re-formed in 1979.

Many other bands have sprung up, some of them experimenting with Irish music in new directions; and some, like Scullion, introducing even broader influences. And the inspiration of Planxty has been strongly felt in the development of the British folk scene, particularly firing a Scottish upsurge. Yet the real legacy is the amazing number of brilliant young flute players, fiddlers and pipers to be found passionately practising their art all over Ireland right now.

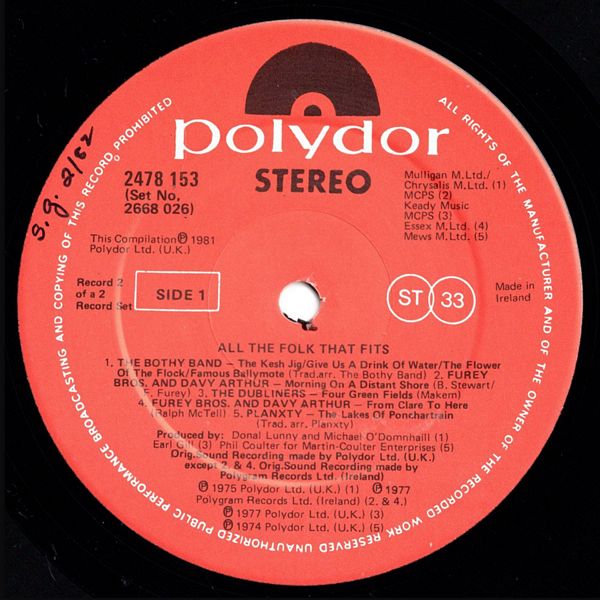

This record is, for me, a supreme indulgence. A substantial portion of the best Irish music has been issued over the years by Polydor, and rifling through their back catalogue searching for a representative selection has been a richly rewarding if arduous exercise. It's a purely personal choice, but I believe it's an important record because it gives the mammoth range and staggering quality of Irish-based folk music over many years a sense of perspective.

It's certainly not intended as a collection merely for buffs and aficianados; nor, I hope, does it pander to obvious commercial instinct (though "Green Fields Of France" was a number one hit in Ireland). The overriding selecting consideration was to choose the very best, though there was another aim too. If the folk music of Ireland is an extension of the people involved, then each track here represents a different facet of that character and the lifestyles that have revolved around it. These tracks not only tell the story of an important cultural movement, they convey a picture of a nation's people.

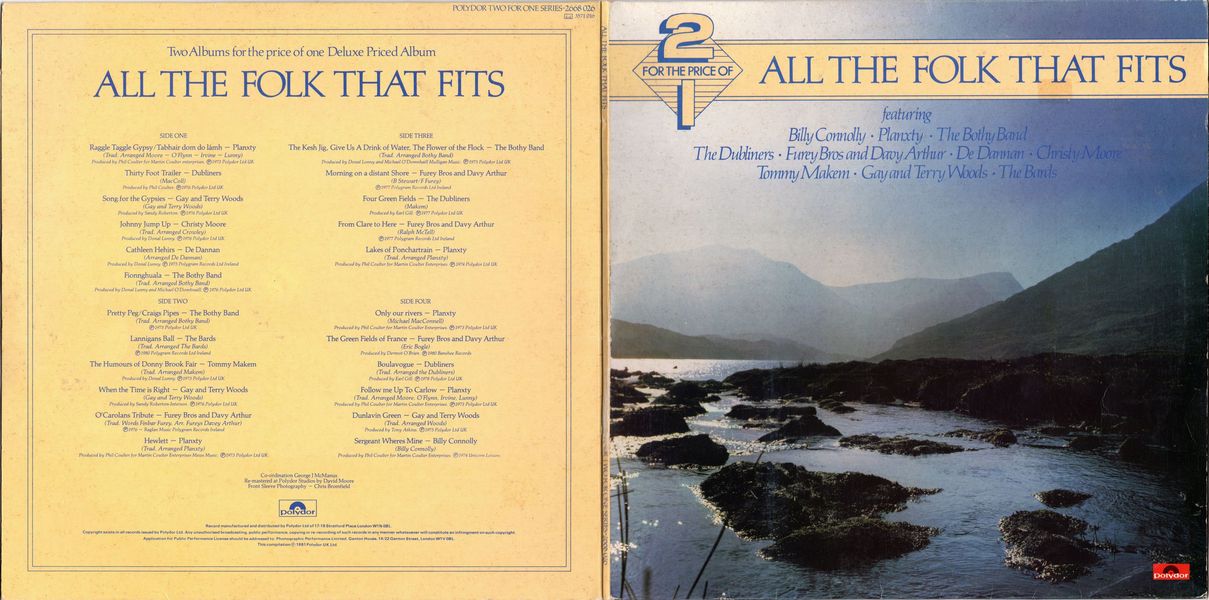

RAMBLERS

I can recall the exact moment I first heard Planxty — and there was no other way to open this album than to recreate that moment. "Raggle Taggle Gipsies" is the first track on the first Planxty album issued in 1973 (it's predecessor "Prosperous" was officially a Christy Moore solo) and it was the freshest, most exhilarating record issued that year, magnificently standing the test of time. The track fully encapsulates the magic of Planxty — understated vocals, Liam achieving miracles on pipes, and Dónal Lunny laying the base of the thrilling tension that undercuts it; it's like the end bit on the fuse of a particularly devastating stick of dynamite. A touch of genius, too, running the song into one of O'Carolan's most beautiful tunes.

"Thirty Foot Trailer" was written by a Scotsman, Ewan MacColI, not specifically about Ireland, but still appropriate to it — the image of a travelling people still holds good in Ireland. It's one of MacColl's most famous songs, but the Dubliners do it as well as anyone, capturing the sadness yet sense of defiance inherent in the song.

It's an image (Say and Terry Woods adapted on "Song For The Gipsies" — the musician as the modern gipsy — a haunting mixture of nostalgia, carefree joy, and melancholia. Gay and Terry knew quite a bit about it. Terry had been a member of Sweeney's Men, both were founders of Steeleye Span, and went on to form their own Woods Band. The records they subsequently made as a duo were consistently good, yet never fitted any commercial pigeon-hole. They refused to play the games of the business, stuck themselves away in a remote part of Ireland, and sadly split up in 1980. They made three albums for Polydor — "The Time Is Right", "Backwoods", and "Renowned" — this is from "The Time Is Right".

Christy Moore left Planxty a year before their demise and reminded everybody he'd been a successful solo artist before he ever joined them. He always was a master with a song like "Johnny Jump Up", also recorded with great effect by the outstanding Cork singer Jimmy Crowley.

De Dannan were one of the first bands to emerge in the wake of Planxty, coming out of Galway to merge the brash brilliance of fiddler Frankie Gavin, with the multi-instrumental talents of Charlie Piggott and the compelling rhythms of Ringo McDonagh and Alec Finn, and the peerless singing of Dolores Keane (an early departure). "Cathleen Hehirs" is from their first album together in 1975, called "De Dannan".

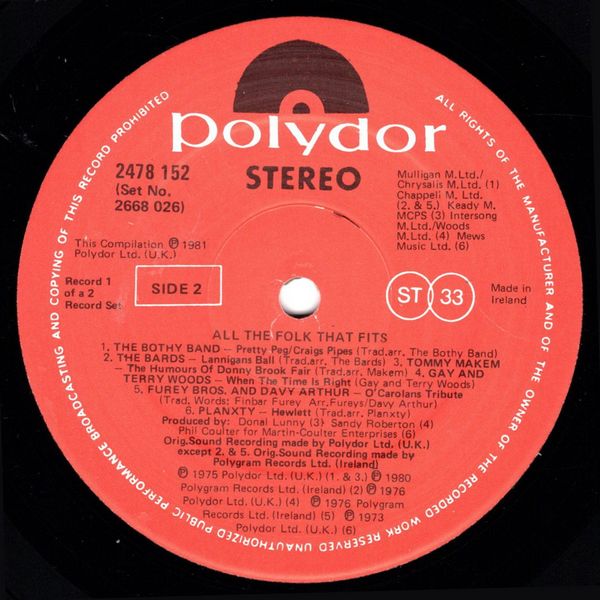

Yet the other giants in the Irish story are the Bothy Band. They took their name from the pick-up musicians formed from travelling workers, and went a long way towards emulating the wild spontaneous excitement they engendered. The Bothies did, however, have a much wider range than Planxty could ever encompass — as demonstrated by "Fionghualla", an astonishing bout of Gaelic mouth music. The version here is from "Old Hag You Have Killed Me", their second album, and they used to introduce it as "our greatest hit" in deference to the handful of copies sold when Polydor issued it as a single. The number had previously been included on an obscure album called "Celtic Folkweave" by Bothy Band forerunners Munroe.

RENEGADES

The other trump card held by the Bothy Band was the stunning singing of their diminutive keyboard player, Tríona Ní Dhomhnaill, later to be whisked to America to work with Linda Ronstadt! With ex-Planxty man Dónal Lunny as one of their founders, the Bothies built on Planxty's inspiration and played with electrifying flair and a marked lack of inhibition. They boasted the wildest piping in captivity (Paddy Keenan), a young equivalent of the travelling style of piping exemplified by the Dorans. The fierceness of Keenan's playing — which once moved Dónal Lunny to describe him as "the Jimi Hendrix of the pipes" — is perfectly demonstrated by his solo on "Craig's Pipes" from the superb Bothy debut album in 1975. Sadly the Bothies were to encounter similar pressures to those which pulled down Planxty — brilliant fiddler Tommy Peoples was an early casualty — and the group never seemed disciplined enough to reap the international rewards that should have been their due. They finally fragmented irretrievably in 1979.

The Bards, on the other hand, are virtually unknown in folk circles, but their version of that old warhorse "Lannigan's Ball" is a classic. Tommy Makem is one of the legendary names in Irish folk music through his graphic singing with the Clancy Brothers — godfathers of Irish ballad groups, and forever synonymous with aran sweaters. Makem and his partner Liam Clancy now spend much of their time in America, but in 1974 Makem produced an impressive solo album "Ever The Wind". "The Humours Of Donnybrook Fair" is taken from it.

I've always been fascinated by the lyric to "When The Time Is Right", the title track of the second Gay and Terry Woods' "Polydor" album. It seemed to be an anthem for them, yet it's full of the romanticism of the musician as hobo, also reflected in "Song For The Gipsies". It's strength is compounded by one of the best vocal performances Terry Woods has ever produced.

Turlough O'Carolan was a blind harpist from Derry, born in 1670 and died in 1738. He composed numerous superb tunes, usually for a specific occasion, and often preluded by the Irish word of affectionate tribute, "planxty". His name is now revered, yet it would be totally forgotten were it not for a composer/harpsichord player called "Seán O'Riada, who himself died in the Sixties, but devoted much of his later life arranging and popularising the music of O'Carolan. Seán O'Riada's orchestra Ceoltoiri Chualann evolved directly into the Chieftains following O'Riada's death, and O'Carolan's magical melodies have become a staple diet for young Irish musicians. Finbar Furey wrote "O'Carolan's Tribute" to the tune of "Planxty Irwin", apparently in some frustration at the lack of a public monument to the great man, and we follow it here with another O'Carolan tune "Hewlet", from Planxty's "The Well Below The Valley".

REFUGEES

"The Kesh Jig" is a dynamic a piece of music as you're ever likely to hear. It was fearsome enough as the opening cut of the Bothy Band's first album, yet they outstripped even that on their last album "After Hours", recorded live in Paris. In many ways it was a sad album — always erratic on stage they were in some disarray at this point in their career, and the album is disjointed. Yet "The King Jig" is a blistering epitaph.

Emigration has been a bitter fact of life in Ireland through the centuries, whether through famine, oppressive landlords, unemployment, war, or simply wanderlust. Such human tragedy has also produced some hearbreakingly moving music. Four widely divergent examples follow. There's such a vivid air of mournfulness in the Fureys' "Morning On A Distant Shore" someone somewhere must feature it as the theme tune to a movie, and the Dubliners have never been more evocative than on "Four Green Fields". Ironically, though, one of the best songs about Irish emigration is written by an Englishman, Ralph McTell, who'd never ever been to Clare when he wrote "From Clare To Here", based on the loneliness of the Irishmen he met working on a building site. "Lakes Of Pontchartrain" is about an Irishman caught up in the American civil war — Paul Brady's later epic version of the song often makes people forget what a staggering job Planxty did with it (before Brady joined them) in the first place.

REBELS

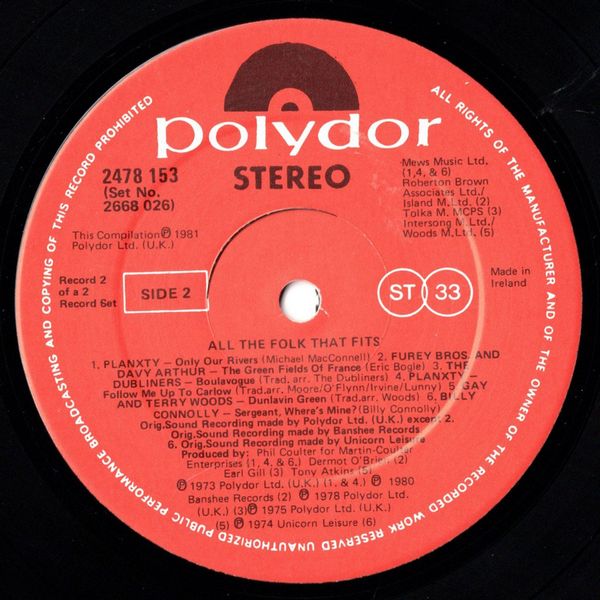

Rebel songs have always abounded in Ireland and continue to do so, but hopefully this side of the record proves they don't always have to take the form of ranting choruses. "Only Our Rivers", written by Michael MacConnell (brother of Cathal from Boys Of The Lough) is surely the best modem song on the subject. Considered, understated, and yet more emotional than any fist-thumping clarion call.

"Green Fields Of France" is also a modem song (written by a Scotsman, Eric Bogle) about the First World War. It's interesting that Ireland adopted it with such passion when the Fureys put it out as a single in 1979, and is also notable for a rare vocal from Finbar Furey.

The Dubliners delved deeply into history for "Boulavogue", recorded by them during the time Jim McCann was with the band following the temporary departure of Ronnie Drew. He brought to them a sophistication that wasn't characteristic but nevertheless added a new dimension.

"Follow Me Up To Carlow" is one of the most compulsive tracks Planxty ever recorded, featured on their first album, and Gay and Terry Woods never did anything quite as climatic as "Dunlavin Green", again looking deep into Irish history. Billy Connolly's "Sergeant Where's Mine" shows a side of him few are aware of and offers a perspective on the situation. The song is about a Scottish soldier serving in Ireland, and shows there are misgivings on that side too …

Colin Irwin Melody Maker