|

|

Sleeve Notes

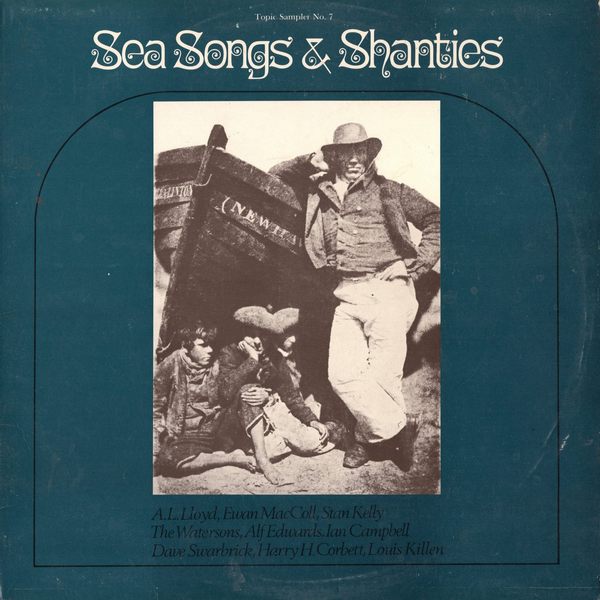

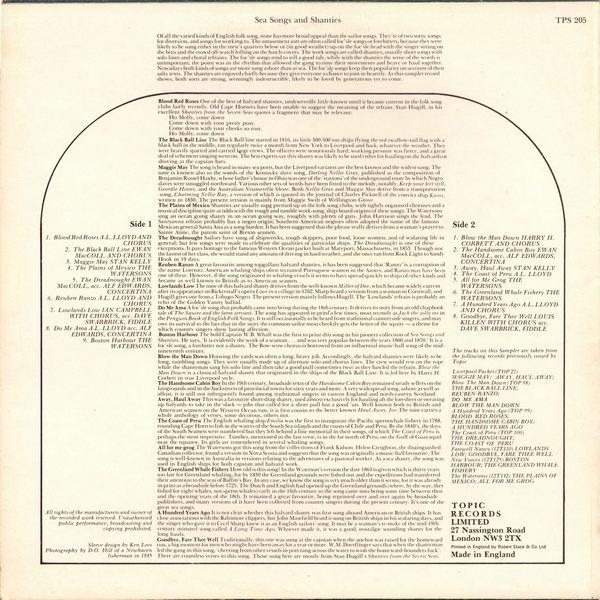

Sea Songs and Shanties

Of all the varied kinds of English folk song, none has more broad appeal than the sailor songs. They're of two sorts: songs for diversion, and songs for working to. The amusement sort are often called foc'sle songs or forebitters, because they were likely to be sung either in the men's quarters below or (in good weather)up on the foc'sle head with the singer sitting on the bitts and the crowd off-watch lolling on the hatch-covers. The work songs are called shanties, usually short songs with solo lines and choral refrains. The foc'sle songs tend to tell a good tale, while with the shanties the sense of the words is unimportant; the point was in the rhythm that allowed the gang to time their movements and heave or haul together. Nowadays both kinds of songs are more sung ashore than at sea. The foc'sle songs keep their popularity on account of their salty lexis. The shanties are enjoyed chiefly because they give everyone a chance to join in heartily. As this sampler record shows, both sorts are strong, seemingly indestructible, likely to be loved by generations yet to come.

Blood Red Roses — One of the best of halyard shanties, undeservedly little-known until it became current in the folk song clubs fairly recently. Old Cape Homers have been unable to suggest the meaning of the refrain. Stan Hugill, in his excellent Shanties from the Seven Seas quotes a fragment that may be relevant:

Ho Molly, come down

Come down with your pretty posy.

Come down with your cheeks so rosy.

Ho Molly, come down

The Black Ball Line — The Black Ball line started in 1816, its little 300-500 ton ships flying the red swallow-tail flag with a black ball in the middle, ran regularly twice a month from New York to Liverpool and back, whatever the weather. They were heavily sparred and carried large crews. The officers were notoriously hard, working pressure was fierce, and a great deal of vehement singing went on. The best experts say this shanty was likely to be used either for hauling on the halyards or shoving at the capstan bars.

Maggie May — The song is heard in many sea ports, but the Liverpool variants are the best known and the widest sung. The tune is known also to the words of the Kentucky slave song, Darling Nellie Gray, published as the composition of Benjamin Russel Haxby, whose father's house in Ohio was one of the 'stations' of the underground route by which Negro slaves were smuggled northward. Various other sets of words have been fitted to the melody, notably, Keep your feet still, Geordie Hinny. and the Australian Neumereila Shore. Both Nellie Gray and Maggie May derive from a transportation song, Charming Nellie Ray, a version of which is quoted in the journal of Charles Picknell of the convict ship Kains, wrillen in 1830. The present version is mainly from Maggie Swift of Wellington Grove.

The Plains of Mexico — Shanties are usually sung prettied up in the folk song clubs, with tightly organised choruses and a musical discipline quite at odds with the rough and tumble work-song, ship-board origins of these songs. The Watersons sing an ocean going shanty in an ocean going way, roughly with plenty of guts. John Harrison sings the lead. The Santyanna refrain probably has a negro origin; Southern American negroes often adopted the name of the famous Mexican general Santa Ana as a song burden. It has been suggested that the phrase really derives from a seaman's prayer to Sainte Anne, the patron saint of Breton seamen.

Reuben Ranzo — A great favourite among topgallant halyard shanties, it has been suggested that 'Ranzo' is a corruption of the name Lorenzo. American whaling ships often recruited Portuguese seamen in the Azores, and Ranzo may have been one of these. However, if the song originated in whaling vessels it seems to have spread quickly to ships of other kinds and became as well known to British as to American seamen.

Lowlands Low — The tune of this halyard shanty derives from the well-known Miller of Dee, which became widely current after its appearance in Bickerstaff's opera Love in a village in 1762. Sharp heard a version from a seaman in Cornwall, and Hugill gives one from a Tobago Negro. The present version mainly follows Hugill. The 'Lowlands' refrain is probably an echo of the Golden Vanity ballad.

Do Me Ama — A foc'sle song that probably came into being during (he 18th century. It derives its story from an old chapbook tale of The Squire and the farm servant. The song has appeared in prim a few limes, most recently as Jack the jolly tar in the Penguin Book of English Folk Songs. It is still occasionally to be heard from traditional countryside singers, and may owe its survival to the fact that in the story the common sailor most cheekily gets the better of the squire — a theme for which country singers show lasting affection.

Boston Harbour — The bold Captain W.B. Whall was the first to print this song in his pioneer collection of Sea Songs and Shanties. He says, 'It is evidently the work of a seaman . . . and was very popular between the years 1860 and 1870.' It is a foc'sle song, a forebitter not a shanly. The Bow-wow chorus is borrowed from an influential music-hall song of the mid-nineteenth century.

Blow the Man Down — Hoisting the yards was often a long, heavy job. Accordingly, the halyard shanties were likely to be long, rambling songs. They were usually made up of alternate solo and chorus lines. The crew would rest on the rope while the shantyman sang his solo line and then take a good pull (sometimes two) as they bawled the refrain. Blow the Man Down is a classical halyard shanty that originated in the ships of the Black Ball Line. It is led here by Harry H. Corbett in true Liverpool style.

The Handsome Cabin Boy — In the 19th century, broadside texts of the Handsome Cabin Boy remained steady sellers on the fairgrounds and in the backstreets of provincial towns for sixty years and more. A very widespread song, ashore as well as afloat, it is still not infrequently found among traditional singers in eastern England and north-eastern Scotland.

Away, Haul Away — This was a favourite short-drag shanty, used almost exclusively for hauling aft the foresheet or sweating up halyards to take in. the slack — jobs that called for a short pull but a good 'un. Well known both to British and American seamen on the Western Ocean run, it is first cousin to the better-known Haul Away, Joe. The tune carries a whole anthology of verses, some decorous, others not.

The Coast of Peru — The English whaling ship Emilia was the first to inaugurate the Pacific spermwhale fishery in 1788, rounding Cape Horn to fish in the waters of the South Sea Islands and the coasts of Chile and Peru. By the 1840's, the days of the South Seamen were numbered but they left behind a fine memorial in their songs, of which The Coast of Peru is perhaps the most impressive. Tumbez, mentioned in the last verse, is in the far north of Peru, on the Gulf of Guayaquil near the equator. Its girls are remembered in several whaling songs.

All for me grog — The Watersons got this song from the collections of Frank Kidson. Helen Creighton, the distinguished Canadian collector, found a version in Nova Scotia and suggests that the song was originally a music-hall favourite. The song is well-known in Australia in versions relating to the adventures of a pastoral worker. As a sea shanty, the song was used in English ships for both capstan and halyard work.

The Greenland Whale Fishery — How old is this song? In the Waterson's version the date 1864 is given which is thirty years too late for Greenland whaling, for by 1830 the Greenland grounds were fished out and the expeditions had transferred their attention to the seas of Baffin's Bay. In any case, we know the song is very much older than it seems, for it was already in print as a broadside before 1725. The Dutch and English had opened up the Greenland grounds (where, by the way, they fished for right whales, not sperm whales) early in the 16th century so the song came into being some time between then and the opening years of the 18th. It remained a great favourite, being reprinted over and over again by broadside publishers, and many versions of it have been collected from country singers during the present century. It's one of the great sea songs.

A Hundred Years Ago — It is not clear whether this halyard shanty was first sung aboard American or British ships. It has close associations with the Baltimore clippers, but John Masefield heard it sung on British ships in his seafaring days, and the singer who gave it to Cecil Sharp knew it as an English sailors' song. It may be a seaman's re-make of the mid-19th century minstrel song called A Long Time Ago. Whoever made it, it was a good, nostalgic sounding shanty for the long hauls.

Goodbye, Fare Thee Well — Traditionally, this one was sung at the capstan when the anchor was raised for the homeward run, a big moment for men who might have been away for a year or more. W.M. Doerflinger says that when the shantyman led the gang in this song, 'cheering from other vessels in port rang across the water to wish the homeward-bounders luck'. I'here are countless verses to this song. Those sung here are mostly from Stan Hugill's Shanties from the Seven Seas.