|

|

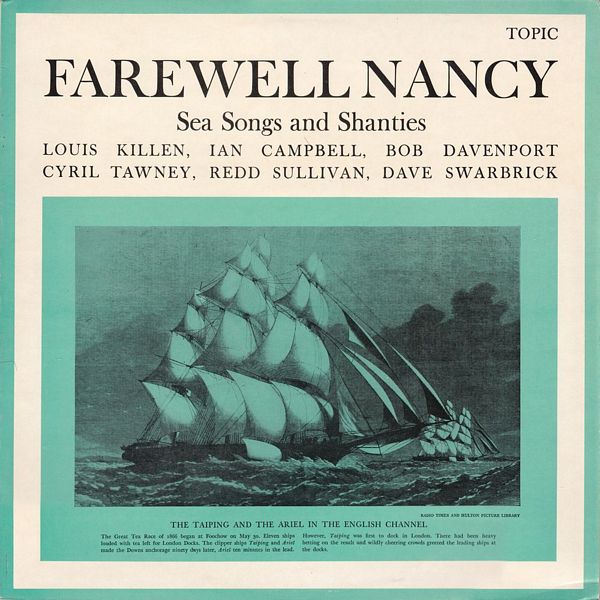

Sleeve Notes

The insurance clerk dreams of tall ships, full-dressed, scudding through tropical seas, and of coarse hairy men bellowing wild songs as they haul on the ropes. Well, the old sailing ships weren't all that romantic, nor were the crews always so brutish. Now and then, in museums or curio shops we find sweet mermaids carved on cokernuts, classical scenes scrimshawed on spermwhale teeth, an embroidered pillow-case with two hearts and an anchor, delicate fond things worked by tarry hands in a stuffy foc'sle, and we're reminded that if some sailing-ship sailors were of the ringtailed roarer kind, others were reflective men, masters of their own vernacular culture both at work and in leisure. So too with the songs they created; some are as rough as a teak board, others have words of deep sense spliced to tunes full of secrets. There were fine poets, splendid composers who felt more at ease holding a capstan-bar than a pen.

It's well-known that sailor songs are of two kinds, shanties and forebitters. Shanties were for singing at work, forebitters for singing at leisure. Shanties were functional songs whose purpose was to get men to pull or push together so the job would go easier. Forebitters were diversionary songs, sung to ease the mind and make a hard life tolerable. Forebitters usually had fixed texts telling a coherent story. Shanties often consisted of whatever words floated into the shantyman's mind in the course of the job; they were made of scraps and might be expanded or contracted, forty verses or four, according to the length of the task in hand. As for style, some singers sang with plenty of ornaments—‘hitches', the sailors called them—while others sang undecorated. Some sang with free, hardly measurable rhythm, others sang bang on the beat. There were no rules, except for the crowd on the choruses of the work-songs; they had to sing full, plain and regular, if they were to pull together. To the debated question whether seamen sang the shanty refrains in harmony the answer seems to be: some might but most didn't. But nowadays, when shanties are sung for fun and not in earnest, it's usual to brighten them with harmonies, and to sing them faster and jerkier than their true purpose demanded. Both shanties and forebitters are wellnigh indestructible; they can stand any treatment except the quaint and genteel. All the same, one doesn't often hear them sung so convincingly as they are on this record.

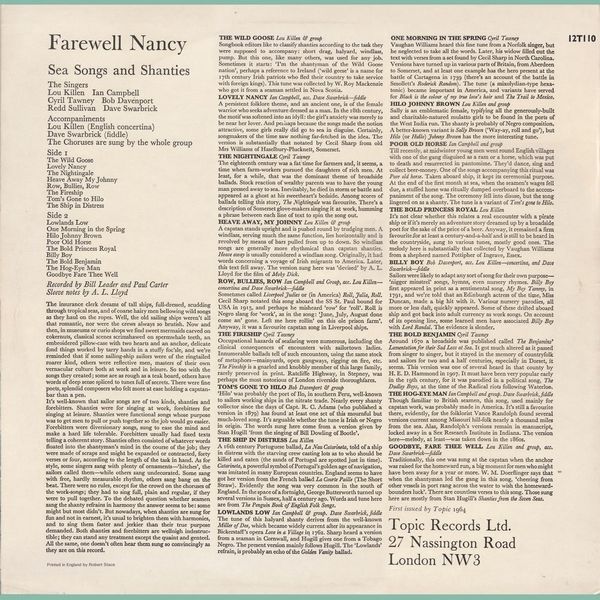

THE WILD GOOSE: Lou Killen & group

Songbook editors like to classify shanties according to the task they were supposed to accompany: short drag, halyard, windlass, pump. But this one, like many others, was used for any job. Sometimes it starts: ‘I'm the shantyman of the Wild Goose nation', perhaps a reference to Ireland (‘wild geese' is a name for 17th century Irish patriots who fled their country to take service with foreign kings). This tune was collected by W. Roy Mackenzie who got it from a seaman settled in Nova Scotia.

LOVELY NANCY: Ian Campbell, acc. Dave Swarbrick—fiddle

A persistent folklore theme, and an ancient one, is of the female warrior who seeks adventure dressed as a man. In the i8th century, the motif was softened into an idyll: the girl's anxiety was merely to be near her lover. And perhaps because the songs made the notion attractive, some girls really did go to sea in disguise. Certainly, songmakers of the time saw nothing far-fetched in the idea. The version is substantially that notated by Cecil Sharp from old Mrs. Williams of Haselbury-Plucknett, Somerset.

THE NIGHTINGALE: Cyril Tawney

The eighteenth century was a fat time for farmers and, it seems, a time when farm-workers pursued the daughters of rich men. At least, for a while, that was the dominant theme of broadside ballads. Stock reaction of wealthy parents was to have the young man pressed away to sea. Inevitably, he died in storm or battle and appeared as a ghost at his sweetheart's bedside. Among scores of ballads telling this story, The Nightingale was favourite. There's a description of Somerset glove-makers singing it at work, humming a phrase between each line of text to spin the song out.

HEAVE AWAY, MY JOHNNY: Lou Killen & group

A capstan stands upright and is pushed round by trudging men. A windlass, serving much the same function, lies horizontally and is revolved by means of bars pulled from up to down. So windlass songs are generally more rhythmical than capstan shanties. Heave away is usually considered a windlass song. Originally, it had words concerning a voyage of Irish migrants to America. Later, this text fell away. The version sung here was ‘devised' by A. L. Lloyd for the film of Moby Dick.

ROW, BULLIES, ROW: Ian Campbell and Group, acc. Lou Killen— concertina and Dave Swarbrick—fiddle

Sometimes called Liverpool Judies or (in America) Roll, Julia, Roll. Cecil Sharp notated this song aboard the SS St. Paul bound for USA in 1915, and perhaps he misheard ‘row' for ‘roll'. Roll is Negro slang for ‘work', as in the song: ‘June, July, August done come an' gone. Left me here rollin' on this ole prison farm'. Anyway, it was a favourite capstan song in Liverpool ships.

THE FIRESHIP: Cyril Tawney

Occupational hazards of seafaring were numerous, including the clinical consequences of encounters with sailortown ladies. Innumerable ballads tell of such encounters, using the same stock of metaphors—mainyards, open gangways, rigging on fire, etc. The Fireship is a gnarled and knobbly member of this large family, rarely preserved in print. Ratcliffe Highway, in Stepney, was perhaps the most notorious of London riverside thoroughfares.

TOM'S GONE TO HELO: Bob Davenport & group

‘Hilo' was probably the port of Ilo, in southern Peru, well-known to sailors working ships in the nitrate trade. Nearly every shanty collector since the days of Capt. R. C. Adams (who published a version in 1879) has found at least one set of this mournful but much-loved song. It's arguable whether the tune is Irish or Negro in origin. The words sung here come from a version given by Stan Hugill ‘from the singing of Bill Dowling of Bootle'.

THE SHIP IN DISTRESS: Lou Killen

A 16th century Portuguese ballad, La Nau Catarineta, told of a ship in distress with the starving crew casting lots as to who should be killed and eaten (the sands of Portugal are spotted just in time). Catarineta, a powerful symbol of Portugal's golden age of navigation, was imitated in many European countries. England seems to have got her version from the French ballad La Courte Faille (The Short Straw). Evidently, the song was very common in the south of England. In the space of a fortnight, George Butterworth turned up several versions in Sussex, half a century ago. Words and tune here are from The Penguin Book of English Folk Songs.

ONE MORNING IN THE SPRING: Cyril Tawney

Vaughan Williams heard this fine tune from a Norfolk singer, but he neglected to take all the words. Later, his widow filled out the text with verses from a set found by Cecil Sharp in North Carolina. Versions have turned up in various parts of Britain, from Aberdeen to Somerset, and at least one example has the hero present at the battle of Cartagena in 1739 (there's an account of the battle in Smollett's Roderick Random). The tune- (a mixolydian-type hexa-tonic) became important in America, and variants have served for Black is the colour of my true love's hair and The Trail to Mexico.

HILO JOHNNY BROWN: Lou Killen and group

Sally is an emblematic female, typifying all the generously-built and charitable-natured mulatto girls to be found in the ports of the West India run. The shanty is probably of Negro composition. A better-known variant is Sally Brown (‘Way-ay, roll and go'), but Hilo (or Hullo) Johnny Brown has the more interesting tune.

POOR OLD HORSE: Ian Campbell and group

Till recently, at midwinter young men went round English villages with one of the gang disguised as a ram or a horse, which was put to death and resurrected in pantomime. They'd dance, sing and collect beer-money. One of the songs accompanying this ritual was Poor old horse. Taken aboard ship, it kept its ceremonial purpose. At the end of the first month at sea, when the seamen's wages fell due, a stuffed horse was ritually dumped overboard to the accompaniment of the song. The ceremony fell into disuse, but the song lingered on as a shanty. The tune is a variant of Tom's gone to Hilo.

THE BOLD PRINCESS ROYAL: Lou Killen

It's not clear whether this relates a real encounter with a pirate ship or if it's merely an adventure story dreamed up by a broadside poet for the sake of the price of a beer. Anyway, it remained a firm favourite for at least a century-and-a-half and is still to be heard in the countryside, sung to various tunes, mostly good ones. The melody here is substantially that collected by Vaughan Williams from a shepherd named Pottipher of Ingrave, Essex.

BILLY BOY: Bob Davenport, acc. Lou Killen—concertina, and Dave Swarbrick—fiddle

Sailors were likely to adapt any sort of song for their own purpose— ‘ n-word minstrel' songs, hymns, even nursery rhymes. Billy Boy first appeared in print as a sentimental song, My Boy Tammy, in 1791, and we're told that an Edinburgh actress of the time, Miss Duncan, made a big hit with it. Various nursery parodies, all more or less daft, quickly appeared. Some of these drifted aboard ship and got back into adult currency as work songs. On account of its opening line, some learned men have associated Billy Boy with Lord Randal. The evidence is slender.

THE BOLD BENJAMIN: Cyril Tawney

Around 1670 a broadside was published called The Benjamins' Lamentation for their Sad Loss at Sea. It got much altered as it passed from singer to singer, but it stayed in the memory of countryfolk and sailors for two and a half centuries, especially in Dorset, it seems. This version was one of several heard in that county by H. E. D. Hammond in 1907. It must have been very popular early in the 19th century, for it was parodied in a political song, The Dudley Boys, at the time of the Radical riots following Waterloo.

THE HOG-EYE MAN: Ian Campbell and group. Dave Swarbrick, fiddle

Though familiar to British seamen, this song, used mainly for capstan work, was probably made in America. It's still a favourite there, evidently, for the folklorist Vance Randolph found several versions current among Missouri hill-folk nearly a thousand miles from the sea. Alas, Randolph's versions remain in manuscript, locked away in a Sex Research Institute in Indiana. The version here—melody, at least—was taken down in the 1860s.

GOODBYE, FARE THEE WELL: Lou Killen and group, acc. Dave Swarbrick—fiddle

Traditionally, this one was sung at the capstan when the anchor was raised for the homeward run, a big moment for men who might have been away for a year or more. W. M. Doerflinger says that when the shantyman led the gang in this song, ‘cheering from other vessels in port rang across the water to wish the homeward-bounders luck'. There are countless verses to this song. Those sung here are mostly from Stan Hugill's Shanties from the Seven Seas.