|

|

|

| more images |

Sleeve Notes

Luke Kelly …

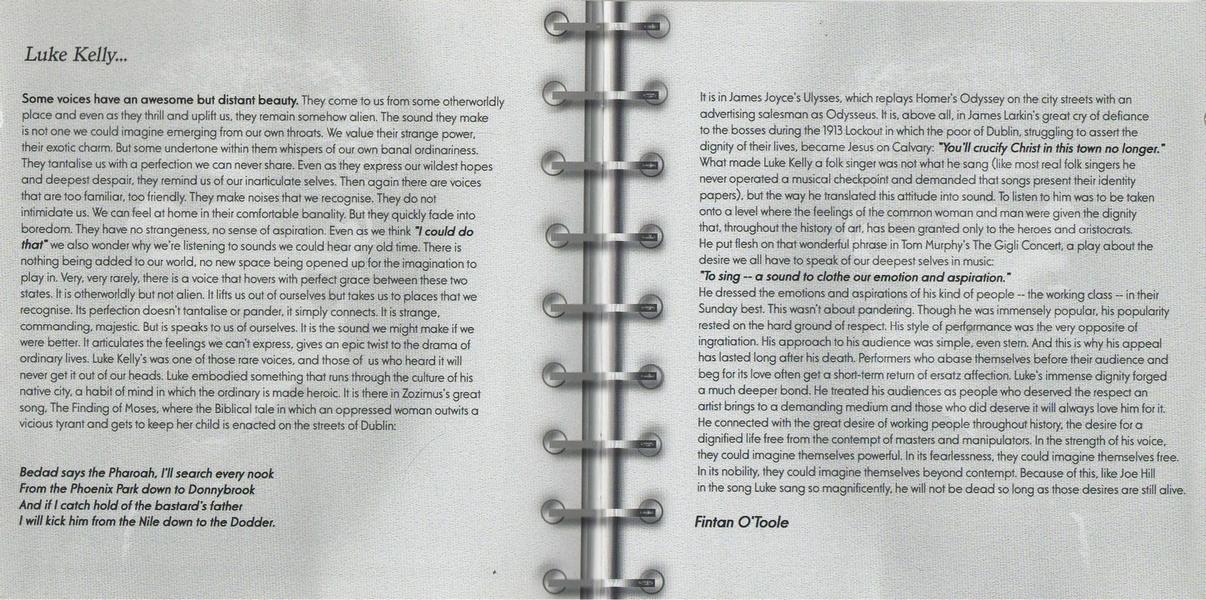

Some voices have an awesome but distant beauty. They come to us from some otherworldly place and even as they thrill and uplift us, they remain somehow alien. The sound they make is not one we could imagine emerging from our own throats. We value their strange power, their exotic charm. But some undertone within them whispers of our own banal ordinariness. They tantalise us with a perfection we can never share. Even as they express our wildest hopes and deepest despair, they remind us of our inarticulate selves. Then again there are voices that are too familiar, too friendly. They make noises that we recognise. They do not intimidate us. We can feel at home in their comfortable banality. But they quickly fade into boredom. They have no strangeness, no sense of aspiration. Even as we think "I could do that" we also wonder why we're listening to sounds we could hear any old time. There is nothing being added to our world, no new space being opened up for the imagination to play in. Very, very rarely, there is a voice that hovers with perfect grace between these two states. It is otherworldly but not alien. It lifts us out of ourselves but takes us to places that we recognise. Its perfection doesn't tantalise or pander, it simply connects. It is strange, commanding, majestic. But is speaks to us of ourselves. It is the sound we might make if we were better. It articulates the feelings we can't express, gives an epic twist to the drama of ordinary lives. Luke Kelly's was one of those rare voices, and those of us who heard it will never get it out of our heads. Luke embodied something that runs through the culture of his native city, a habit of mind in which the ordinary is made heroic. It is there in Zozimus's great song. The Finding of Moses, where the Biblical tale in which an oppressed woman outwits a vicious tyrant and gets to keep her child is enacted on the streets of Dublin:

Bedad says the Pharoah. I'll search every nook

From the Phoenix Park down to Donnybrook

And if I catch hold of the bastard's father

I will kick him from the Nile down to the Dodder.

It is in James Joyce's Ulysses, which replays Homer's Odyssey on the city streets with an advertising salesman as Odysseus. It is, above all, in James Larkin's great cry of defiance to the bosses during the 1913 Lockout in which the poor of Dublin, struggling to assert the dignity of their lives, became Jesus on Calvary: "You'll crucify Christ in this town no longer."

What made Luke Kelly a folk singer was not what he sang (like most real folk singers he never operated a musical checkpoint and demanded that songs present their identity papers), but the way he translated this attitude into sound. To listen to him was to be taken onto a level where the feelings of the common woman and man were given the dignity that, throughout the history of art, has been granted only to the heroes and aristocrats. He put flesh on that wonderful phrase in Tom Murphy's The Gigli Concert, a play about the desire we all have to speak of our deepest selves in music: "To sing — a sound to clothe our emotion and aspiration."

He dressed the emotions and aspirations of his kind of people — the working class — in their Sunday best. This wasn't about pandering. Though he was immensely popular, his popularity rested on the hard ground of respect. His style of performance was the very opposite of ingratiation. His approach to his audience was simple, even stern. And this is why his appeal has lasted long after his death. Performers who abase themselves before their audience and beg for its love often get a short-term return of ersatz affection. Luke's immense dignity forged a much deeper bond. He treated his audiences as people who deserved the respect an artist brings to a demanding medium and those who did deserve it will always love him for it. He connected with the great desire of working people throughout history, the desire for a dignified life free from the contempt of masters and manipulators. In the strength of his voice, they could imagine themselves powerful. In its fearlessness, they could imagine themselves free. In its nobility, they could imagine themselves beyond contempt. Because of this, like Joe Hill in the song Luke sang so magnificently, he will not be dead so long as those desires are still alive.

Fintan O'Toole

Tributes

LUKE'S GRAVESTONE

Cold as the wind

That carried your ghost.

Silent as the songs

That remain unsung.

Lonely as an echo

From the Jail of Cluain Meala.

Solitary as your silhouette

Going home by railings

After closing time.

Upright and defiant as your stance

When you challenged the puppets of power

"For what Died the Sons of Roisin?"

Like your voice …

Unweathered by time

This granite gravestone.

Your epitaph — a simple claim;

Between the two great mysteries,

Your place, your name.

LUKE

KELLY

1940

1984

DUBLINER

"Luke was a hard chaw with a heart of gold and the soul of an angel."

My mother first got me interested in performing, by way of making costumes for us kids to wear at parades in Donegal town many years ago. Eddie Cochran first got me interested In rock'n'roll by dint of his exuberance and his use of the guitar as a percussion instrument. And then Luke Kelly got me into folk music for the rest of my life by the sheer power and purity of his singing and his personality. The first song in the folk idiom I ever heard that made me want to find out more about the singer was "Tramps and Hawkers". I actually called Radio Eireann, as it was then, to find out the name of the singer and was surprised to hear it was the Dubliners. It was about 1964 and of course like everyone else I knew of the Dubliners, but I hadn't associated them with such powerful and emotional singing. I was hooked from that day to this, and In later years — too few of them — I was happy to be a friend as well as an admirer, and to share a stage with the man who was, in his day, the greatest interpreter of a narrative ballad most of us will ever hear.

"He had an innate sense of words and how they are married together to a melody, and an extraordinary ability to reproduce an idea he got in his own mind to perfection. He was convinced of his own songs, that was the main thing"

In the early 60's gigs were held (and i believe still are) upstairs at "The international Bar" in Wicklow St., Dublin. It was here that I first met Luke Kelly. He had just returned to Dublin from England. We chatted for a while, and I mentioned to him, that Barney McKenna and myself were "habitues" of O'Donoghue's pub in Merrion Row. Soon after, he began dropping in with his long neck G. Banjo when we would swap and sing songs, and Barney would play jigs and reels on his Tenor Banjo, to the ragged accompaniment of Luke and myself, he soon became a regular. Then we met Ciarán Bourke, who was a student of agriculture, at U. C. D. He spoke very good Irish and played the Tin Whistle and Guitar. With his songs in Irish and English and his tin whistle playing, Luke's vast store of industrial and other songs, which we had not heard before, the Dublin songs, which I was singing, and "Barney's banjo playing, we became a regular feature in O'Donoghues, playing for the shear love of it all. Then one night someone asked if we would play somewhere and get paid. You probably know the rest.

Luke at this time soon established himself in Dublin and indeed all around Ireland and was held in great respect and admiration for his renditions and interpretations of the songs, which he sang with unbelievable conviction. Luke had what I considered a great voice and personality so that he could have sung and interpreted, with success, a song in any area of music. He was not, as many were at the time, constricted to being labeled a folk singer. His taste in music was very catholic, and he would sing whatever songs he wanted to sing. He loved Rock 'N' Roll, and it was said by some that he was a frustrated Rock singer. I found him to be a man of integrity and generosity of spirit, for example, when I would hear him sing some song which would have particularly taken my fancy, he would say very warmly "if you like it why not sing it". This may not seem like a huge gesture, but if you had known some of the singers that I have known you would recognise that such a gesture was almost heroic. On the material front he was just as generous. He helped unobtrusively and often substantially, many a one who had fallen on lean times. I only found out about this by accident. He was also very constant in his political opinions which often led to himself and myself having many heated arguments even though his views and mine were not so very different, because we were more or less aiming at the same target, but were trying to arrive at it from different angles.

He told we once that he was a committed communist, which was more or less corroborated, when in 1968 "the Dubliners" were, due to go to America to appear on the "Ed Sullivan" Show. However, prior to our scheduled departure for America we were touring England, so it was necessary for us to go to the American Embassy in London. When we were presented there, Luke and I were called into an inner sanctum where we were questioned in relation to our political views. Suddenly the official who was questioning us, planked on the table a photograph of Luke aged 17 selling the "Daily Worker" in Birmingham. For some unknown reason we got our visas.

Luke was an avid reader and there were many periods while touring during which there was not a lot of conversation. Luke had been suffering from a brain tumor for a few years and on his last tour of Germany with "The Dubliners", which was in November 1983, he was taken very ill in Mannheim, and was taken to a neurological clinic in Heidelberg.

The next day was a free day for "the 'Dubliners", so I decided to take, a train to Heidelberg to visit Luke. When I arrived at the clinic he was up and about and we sat and talked for about three hours. We covered many subjects both personal and general, it was a most rewarding few hours, we sorted out a few things and we parted as close friends. I cherish the memory of that occasion.

The next time I saw him was at the "Richmond Hospital just before he died.

The time I spent in producing and writing for The Dubliners was maybe the most enjoyable and the most productive of my entire career. One of the reasons was Luke Kelly. Had it not been for Luke I might very well have not written songs like 'Scorn Not His Simplicity' and "The Town I Loved So Well'. The voice I heard in my head while struggling with these songs was unmistakably Luke's.

Luke was no shrinking violet, believe me. If he didn't like a song he'd soon let you know, He was as passionate about his songs as he was about his politics and we crossed swords often, in and out of the studio. That said, he didn't have the closed mind that a lot of folk musicians do. He was very game, and open to new ideas. I remember when I played the piano intro to 'Joe Hill', Luke was as delighted as a kid with a new toy.

I learned a lot about songs and about songwriting from Luke, and he breathed life into my songs in a very special way. Even today I can still get goose pimples when I hear that voice again.

We will never hear his like again.

Phil Coulter

Luke how glad I am that our paths have crossed in that brief window of consciousness that is given to us between the two great mysteries, you were no self-effacing rustic waiting to be coaxed to sing soft sad love songs.

You were as strident as a street in Cricklewood, as brash as a 'Dublin Hackney Driver and you took delight in what you sang, Joy and anger mixed in a powerful blend — that was your hallmark — then as always — joy in the act of singing — anger in the words that spoke of injustice.

You came from the mould of the great commune-ists who knew it was right to rail against the tyranny of class and privilege.

So what signifies? What signifies is that you fulfilled your purpose — that you did not stint in the giving of the talent that was uniquely yours.

Had you been a blade of grass you would have been very green and very tall and very pointed — because all things must be what they are to their fullness.

And when in the future there are those who want to heat, not the froth of fashion in the pop song of the month, but the timeless vision of the true story told, they will listen to you Lukey — you and your likes, if there are such.