|

|

Sleeve Notes

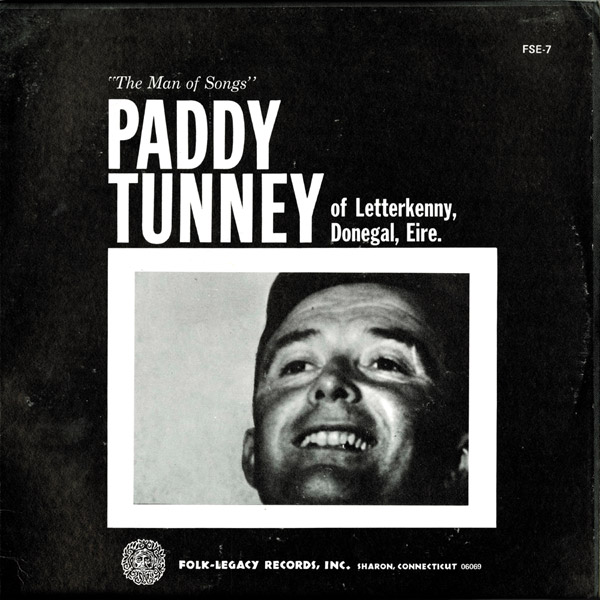

PADDY TUNNEY — "The Man of Songs"

Paddy Tunney was born of Irish parents in Glasgow, Scotland, on January 28, 1921 (the year the Black and Tan war was ended). When he was one month old, his parents returned with him to County Donegal, Ireland. Although Paddy's father is from Donegal and his mother is from Fermanagh, the boundaries of the two families' farms met at the border between the two counties. Paddy lived in Donegal until he was five years old, at which time the family moved back to the old farmstead in County Fermanagh. There on the farm, in a spotless, white-washed house with a thatched roof, among the fields and close to the peat bogs, he grew up hearing the music and the songs that had been in his familv for generations. Paddy's own words tell of his family and its traditions:

"My mother, Mrs. Brigid Tunney, was a fine traditional singer. Though still alive, her voice is failing. She taught me to lilt and sing. Her maiden name was Gallagher, of Rusheen, Templecarron, Pettigo P. O., County Donegal. Her father, Michael Gallagher, was a fine singer and story teller. I remember him taking me on his knee and singing to me. Michael Gallagher was a tall, fair-haired man with a flowing red beard. He had a ruddy complexion and a proud, haughty bearing. He knew both Gaelic and English and had a fine repertoire of folk tales and classical ballads. He could make good 'poteen' (mountain dew) and knew all the journeymen, tinsmiths, tailors, cobblers, weavers, spinners, etc., who travelled around the country when he was a young man. He disliked small, dark men, unless they had the gift of song or poetry. Every year he went to the Station Island of Lough Derg (Diocese of Clogher), County Donegal, on pilgrimage, travelling barefoot all the way, as was the custom then. The memory of this poet-grandfather who died when I was four years old has haunted me for 37 years."

"My father, Patrick Tunney, is a quiet, tall, darkish man at 77. He knows when to speak and when to remain silent. His appearance now is statuesque and he has a quiet pride all his own. In his youth he was a good footballer and a beautiful reel dancer. Lilting, fiddling and melodeon playing were then the only ways of making music."

Paddy went to school in Derryhollow, County Fermanagh, and later to the technical school in Ballyshannon, Donegal. His first job was as a forester, working for the Ministry of Agriculture in Northern Ireland. That was in 1941, the same year in which he became an active member of the Irish Republican Army. Paddy can tell many adventurous tales about this period of his life — of giving extended order drill in dark fields at night and of teaching Irish history while sitting on a creel in a cold, deserted house, with only a candle for light. In June, 1942, he took on the job of road-roller flagman and, at the same time, became a part of the counter-espionage force of the I.R.A.

During the next year, he successfully transported 100 pounds weight of gelignite (a high explosive) sixty-four miles from County Caven to Fermanagh on a bicycle.

In 1943, while carrying 17 pounds of gelignite on a bus, with his bicycle strapped on top of the vehicle, he was stopped at the Beleek border. The gelignite was found, wrapped up in his overalls.

Paddy immediately admitted responsibility for the gelignite and also claimed ownership of some "seditious'documents" which were actually being carried by another man. He was arrested and removed to Derry Gaol. He was tried on May 1st in a Petty Sessions Court at Inniskillen and then put back in jail. Later that summer he was tried by an Orange Jury and found guilty of "possession of explosives with intent to endanger life or damage property". Paddy remained silent throughout the proceedings and was said by the court to be "mute of malice". He was sentenced to seven years penal servitude in H.M. Prison and was removed to the Belfast Gaol where he remained for four and one half years.

While he was in prison he worked in the bootshop, learned Irish (Gaelic) and wrote poetry. He participated in several hunger strikes, protesting against the treatment of political prisoners. For relaxation, he says, he watched the rats running about in the prison yard and exchanged jigs and reels with the other prisoners by tapping on the water pipes in the cells. One August 12th he heard the skirl of pipes as a band of pipers passed up the street outside the prison. Paddy says that this was the only time he ever welcomed the sound of Orangemen. Upon his release from prison he was sent to hospital and, from there, he went home to Fermanagh. After awhile he went to work as a health inspector in Dublin, taking his training at University College. Later he was transferred — first to Donegal, then to Kerry, and finally to Letterkenny, Donegal, where he has remained.

In the Letterkenny Health Office, Paddy met the district nurse, Sheila Bradley, who was called, according to Paddy, "Omar" Bradley, due to her "rousing efficiency". After a romantic courtship in the Donegal hills (among the ancient battle sites and near the seat of the crowning of the Kings of Tyrconnel) they were married in 1950. They now have six children and live in a newly decorated house on the outskirts of Letterkenny.

Paddy's job as health inspector includes inspection of housing, meat and food in general, drugs, general hygiene and environmental hygiene. He covers a large area and recently helped give small-pox innoculations to sailors landing on the Donegal coast. He says that he especially enjoyed this task when it involved stopping a ship from Norway. He describes the sailors as they rowed ashore in an ancient type of high-bowed boat, dressed much as their famous ancestors must have been when, centuries ago, they constantly invaded Ireland. Paddy says, "I suppose this was the first time a Norse ship was ever prevented from landing on the Donegal coast!"

Paddy started singing songs as a child. His mother was a great singer who still has hundreds of fine songs. As Paddy grew up, he became increasingly interested in traditional songs and music. He has collected songs from all over Ireland to add to the wealth of songs in his own family tradition. A prize-winning lilter, he is often called upon to adjudicate singing at local festivals. He has sung for Radio Eiranne and for the BBC. Paddy may also be heard on the Tradition record entitled "The Lark in the Morning" and is one of the many singers included in the Caedmon series, "The Folksongs of Britain. "

Diane Hamilton

NOTES ON THE SONGS

THE HILLS OF GLENSWILLY — Ever since the beginning of the great trek to America which followed the Famine of 1847, songs of exile have been common in the repertory of Irish folksingers. For the most part, they speak of oppression at home and of hopes for a bright future in America. During the late years of the nineteenth century they were in great part replaced by spurious sentimental and nostalgic effusions emanating from outside Ireland, and these in turn have affected the output of local countryside poets.

"The Hills of Glenswilly" is not unaffected by this sentimentality. It was composed, according to Paddy Tunney, by Michael and Brigid McGinley, brother and sister, of Glenswilly, County Donegal. Michael McGinley actually did emigrate to New Zealand, but he returned to spend his last days in Ireland.

MOORLOUGH MARY — The girl celebrated in this song belonged to the mountainy district of Moorlough near Strabane, on the way from Derry to Donnemana. The words were written by the poet Devine of the same district. Local tradition has it that, though they never married, he remained in love with her until they both were very old. The versification shows how, even in the nineteenth century in Tyrone, the unsophisticated poets of the countryside had the ring of Gaelic metrics in their ears. The internal and final assonantal rhymes are placed so as to correspond exactly with the natural stresses of the melodic line, which the poet used as a rhythmic pattern. "I always write my poems to the lie of a good tune" was how a country poet once explained the process to myself. In the following verse, the stressed assonances are underscored:

Paddy's version of the song is one of the most melodious of many. The song spread all over the north of Ireland on Ballad Sheets and was sung to various tunes. Different words and tunes are to be found in the following publications: Irish Street Ballads (Sign of the Three Candles, Fleet Street, Dublin, Ireland); Journal of the Irish Folk Song Society, Vol. II, No. 21 and Vol. IX, No. 15.

LOUGH ERNE SHORE — This song, in subject, manner and expression has all the atmosphere of the Gaelic AISLING or Vision Poem. In the classical Aisling, the poet represents himself as wandering alone, either at twilight or, more usually, in the early morning, when suddenly there appears in his sight a most beautiful maiden (an speirbhean; the woman from heaven). Her physical characteristics are stereotyped — long curling ringleted golden hair, skin white as snow, cheeks rosy red, etc. The poet generally questions her as to her origin, suggesting that she is one of the goddesses of Greek, Roman or Irish mythology, but she usually identifies herself as one of the Sidhe (Fairy Host) or as some personification of Ireland. When she has delivered herself of some apocalyptic message, she disappears from the poet's sight. A complete description of this type of Gaelic poetry, with an account of its principal exponents can be read in "The Hidden Ireland" by Daniel Corkery (Dublin, 1941).

"Lough Erne Shore" contains many of these poetic conventions, and is quite possibly the work of one of Fermanagh's hedge-school masters. These hedge-school masters, proscribed by the law forbidding the education of the Irish, were well versed in Latin, Greek and Irish, but knew English only imperfectly. They often composed songs in English — always to Irish airs — in which they made free use of Latin and Greek mythology. Note the reference in this song to the Greek Sun-god, Phoebus. To the best of my knowledge, this song has never been published in ballad-sheet or any other form. I first heard it from Paddy Tunney Mode: Lah, Pentatonic.

PADDY MOLLOY — This is a song linked with the Fenian Rising of 1867. Many of the Fenians learned their soldiering in America during the Civil War and then returned to Ireland to fight their own battle. Apropos of this 1 might mention a song, not here recorded, but used extensively in America to recruit Fenians for service at home. It is called "Will Ye Come to the Bower?" (the Bower being Ireland) and it is to be found in "Irish Street Ballads" (Sign of the Three Candles, Fleet Street, Dublin).

AS I ROVED OUT — Some of the most charming of ordinary Irish love-songs are in the form of the pastourelle, which has been called the aristocratic progenitor of the "As I roved out one morning" type of ballad. An interesting account of the distribution of this type of ballad in Ireland has been given by Sean O Tuama in a symposium called "Seven Centuries of Irish Learning" (Stationery Office, Dublin, 1961). The song here sung has been equated, rightly or wrongly, with the English ballad "The False Bride" (BBC Recorded Programmes Library), but to me it seems rather to be a mixture of two or three themes taken over from Provencal folk poetry, and one really Irish theme — that of land-hunger. Easily recognizable in the verses are (1) the love debate, (2) chanson de jeune fille, and (3) a folk-memory of amour courtois. The air, which is one of the most elusive in all Irish folk-song and has never been published, is written in the Soh Mode.

THE GREEN FIELDS OF CANADA — This is a genuine Irish Exile song and is to be compared in manner, style and sentiment with "The Hills of Glenswilly".

THE BUACHAILL (BUACHALL) ROE "The Red Haired Boy" — This song, like "Lough Erne Shore", belongs to County Fermanagh, Paddy Tunney's native place. The theme is of constant occurrence in Irish tradition — the praise of the Irishman who has chosen outlawry rather than submission to oppression.

THE MOUNTAIN STREAMS WHERE THE MOORCOCKS CROW — Paddy Tunney considers this song the gem of his whole repertoire. It originated in southern Scotland and has been collected in Fermanagh, Tyrone and North Antrim which faces the Scots coast. It is a love-debate beginning with an early morning meeting in the Aisling manner. There is a striking resemblance between the beginning of this song and that of "Lough Erne Shore". Apparently, in Paddy Tunney's phrase, the twin arts of hunting and love-making go together in the mind of the folk-singer. The melody is an outstanding one with a huge range of an octave-and-a-half, making great demands on the breathing and the stamina of the singer. It is Lah Mode, Hexatonic.

DRAHAAREEN-O MOCHREE (Dreathairin O mo chroi) "My dear little brother" — This is an unusual and tender little song from Munster — unusual in that it expresses the very human love of a man for his younger brother who has gone to fight for England in Spain. It was commonly sung in Munster to the air of "Jimmy, mo Mhile Stor" ("Jimmy, my Thousand Treasures") and was published on ballad sheets at the latter end of the nineteenth century by "Haly, Printer, Cork". The words are printed without music in Joyce's "Old Irish Folk Music and Song", p. 212. Paddy sings it to a most beautiful air learned from his mother and never published.

WHAT PUT THE BLOOD ON YOUR RIGHT SHOULDER, SON? (Child 13) — This famous Classical Ballad needs no introduction to students of American folk-song. "English Songs from the Southern Appalachians", Vol. I, (Oxford University Press) contains ten versions of words and music collected in North Carolina, Virginia and Tennessee. In "Ballads Migrant in New England" (Flanders and Olney, New York) it is published as sung in New Hampshire. Paddy's version comes from Wexford whence it was transported by a tinker group to the North of Ireland. The air exists in three printed versions: Chappell's "Popular Music of Olden Time", p. 522, there called "The Willow Tree"; in Wood's "Songs of Scotland", III, 84, 85; and in Joyce's "Old Irish Folk Music and Song", p. 189, where it is set to a song called "The Gardner's Son". The traditional version sung by Paddy is in the Re Mode.

LILTING —

THE BIRD IN THE BUSH, a reel, danced in lively fashion, lilted in time with fiddlers, fluters and squeeze-box players.

THE SLIGO MAID is a lively tune for a step of a dance. It is hard to resist its rhythm, if you are musical at all. It was known as "Down the Broom" by the older players.

THE LONGFORD COLLECTOR is a tune made famous by Michael Coleman and other Sligo fiddlers. Today, Joe Dowd is perhaps the best exponent of the Sligo style.

THE SAILOR'S BONNET is a reel that is danced in circles. A riddle is spun in the middle of the floor around which the dancers move in ritual formation. As the music quickens, an old bonnet is thrown into the circle in an effort to stop the spinning riddle or sieve. The first man to succeed gets his choice of the best looking girl at the dance that night. That is to say he accompanies her home.

(Above notes on the lilted tunes are by Paddy Tunney)

ROISIN DUBH (Little Black Rose) — In this patriotic song, Ireland is referred to allegorically as The Little Black Rose. The poetic habit of referring to Ireland by allegorical names stems from Gaelic-speaking times when it was a crime to make a patriotic song. Poets evaded the law by personifying Ireland under titles like "Silk of the Kine", "Dark Rosaleen", "Katy Dwyer" and "Kathleen Ni Houlihan". Yeats has immortalised the latter name in "Red Hanrahan's Song about Ireland", but numerous poets, including Mangan and Pearse, have preferred the title of "The Little Dark Rose". Mangan's song, "My Dark Rosaleen", expresses well the spirit of the composition:

LOVELY WILLIE — This song tells its own story. A young girl laments the loss of her true love who was killed by the sword of her father. Paddy Tunney's comment on the killing, though hardly bearing the stamp of historicity, is worth recording: "Murder was the recognized way to dispatch an unpopular suitor some eighty years ago. It was a method very much favored by the so-called Gentry."

The words and air are to be found in "Irish Street Ballads", where the air is compared with that of "The Young Maid's Love" in the same volume. Consult also the Journal of the English Folk Song Society, Vol. IV, No. 21, "The Inconstant Lover; Lovely Willie". Paddy's version of the melody is a mixture of Lah and Soh Modes.

A NOTE ON PADDY TUNNEY'S SINGING STYLE:

In Ireland, as in most countries in Northern Europe, the development of music was primarily instrumental (Curt Sachs; "The Rise of Music in the Ancient World). In Irish literary history, the recitation of poetry was invariably accompanied by the music of the harp. This was measured music and its main feature was the melodic and rhythmic development of the music from verse to verse. This development led to complicated variations of basic musical lines which, however, always synchronised with the poetic line or stanza.

In my opinion, this practice of variation spread in time from instrumentalist to singer and when, with the destruction of the Gaelic Polity in 1601, instrumentation was gradually repressed (harpers and poets were criminals by law), the sole inheritors of the musical tradition were the singers, fiddlers and pipers. Those singers who clung to whatever remnants of the old music survived among the fiddlers and pipers, naturally continued to sing in the style which we today regard as highly decorative. It is slowly disappearing in the Gaelicspeaking areas where, as in a last redoubt, it survived even to the beginning of this century.

Donegal is one of the largest Gaelic-speaking districts in Ireland, and Paddy's mother, the source of his tradition, hails from Donegal. Peter Kennedy once remarked to me that the singing of Mrs. Tunney reminded him of the playing of the Uillean Pipe. This observation from an Englishman, unacquainted at that time with the Irish tradition, is surely most significant. Personally, I should say that Paddy's singing always reminds me of the expert playing of our best traditional fiddlers — runs, graces, stops, glides and all. It contains the essence of traditional Gaelic singing, and is in that respect quite distinct from any singing style now practised in Ireland by most English-speaking singers.

Sean O Boyle