|

|

Sleeve Notes

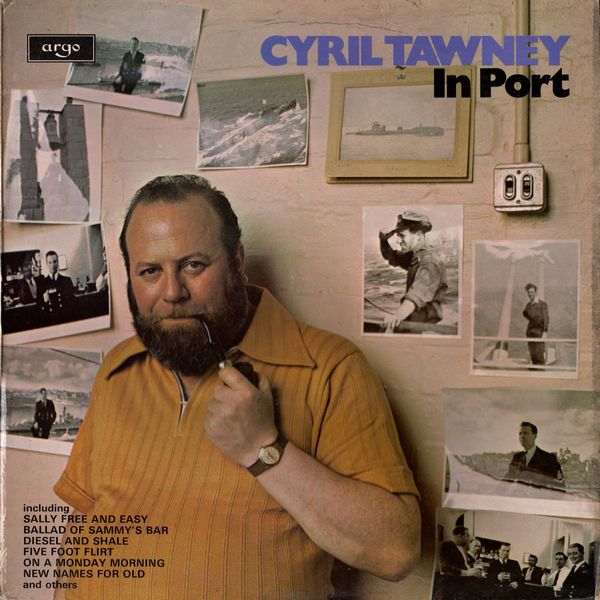

Trying to find a member of the Tawney clan who isn't a song fanatic is like looking for an Edrich who couldn't care less about cricket. Not all the members have the boldness to perform, even at family gatherings, but they nevertheless constitute the most avid listening audience you'll encounter anywhere. We were all brought up on a similar song-diet of Music Hall and Vocal Gems from the Shows, built upon by a succession of Latest Hits, but by becoming the first to take an interest in songwriting and later in folk song I began to break new ground.

From the age of eighteen I was writing passable stuff in the pop style of the forties and fifties at a steady rate, but being stationed in Scotland and later in even more remote places with the Royal Navy, my work never saw the inside of a publisher's office. Still, I was at least learning my craft I suppose. In fact, the early part of 1955 even saw me among the runners-up in a "Melody Maker" song-writing competition.

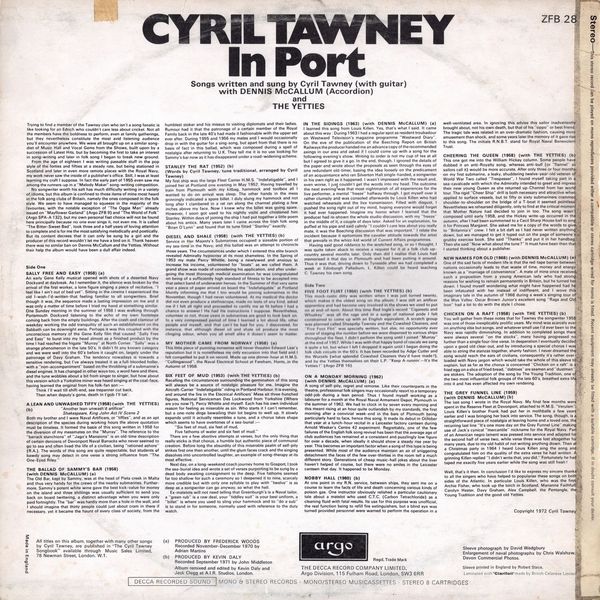

No songwriter worth his salt has much difficulty writing in a variety of idioms, but this album is confined to those items of mine most heard in the folk song clubs of Britain, namely the ones composed in the folk style. We seem to have managed to squeeze in the majority of the favourites, with the notable exception of "The Oggie Man" already issued on "Mayflower Garland" (Argo ZFB 9) and "The World of Folk" (Argo SPA-A 132), but my own personal first choice will not be found here principally because no one ever sings it, not even me. It is called "The Bitter-Sweet Bed", took three and a half years of loving attention to complete and is for me the most satisfying melodically and poetically. But its content decrees that it can only be sung by a girl and the producer of this record wouldn't let me have a bird on it. Thank heaven there was no similar ban on Dennis McCallum and the Yetties. Without their help the album would have been a dull affair indeed.

Sally Free And Easy (1958)

An early Gene Kelly musical opened with shots of a deserted Navy Dockyard at daybreak. As I remember it, the silence was broken by the arrival of the first worker, a lone figure singing a piece of recitative, "I feel like I ain't out of bed yet". Sitting in the cinema I experienced the old I-wish-I'd-written-that feeling familiar to all songwriters. Brief though it was, the sequence made a lasting impression on me and it was only a matter of time before I tried my hand at something similar. One Sunday morning in the summer of 1958 I was walking through Portsmouth Dockyard listening to the echo of my own footsteps coming back from the empty buildings After the crash and clamour of weekday working the odd tranquility of such an establishment on the Sabbath can be downright eerie Perhaps it was this coupled with the unconscious memory of the Gene Kelly film that caused Sally Free and Easy" to burst into my head almost as a finished product by the time I had reached the frigate "Murray" at North Corner "Sally a strange phenomenon in the late 50 s. It didn't fit any known category and we were well into the 60's before it caught on, largely under the patronage of Davy Graham. The tendency nowadays is towards a sensitive rendering, but I've always treated it as a full blooded holler, with a "non-accompaniment" based on the throbbing of a submarine's diesel engines. It has changed in other ways too. a word here and there, and the tune wobbles about a bit from singer to singer, but how about this version which a Yorkshire miner was heard singing at the coal-face, having learned the original from his folk-fan son: —

Think I'll wait till shift-end, see trepanner cut back.

Then when deputy's gone, death in t'gob I'll tak'.

A Lean And Unwashed Tiffy (1958)

"Another lean unwash'd artificer"

Shakespeare. King John Act IV Scene 2

Both my brother and I were Naval Artificers, or "tiffies", and as an apt description of the species during working hours the above quotation must be timeless. It formed the basis of this song written in 1958 for the diversion of my messmates on the "Murray". The reference to the "barrack stanchions" of "Jago's Mansions" is an old-time description of certain denizens of Devonport Naval Barracks who never seemed to go to sea and often lived the life of a civilian, being "rationed ashore" (R.A.). The words of this song are quite respectable, but students of bawdy song may detect in one verse a strong influence from "The One-Eyed Riley."

The Ballad Of Sammy's Bar (1958)

The Old Bar, kept by Sammy, was at the head of Pieta creek in Malta and thus very handy for the crews of the nearby submarines. Furthermore, Sammy's potent white wine gave the best kick-value for money on the island and three shillings was usually sufficient to send you back on board twittering, a distinct advantage when you were only paid fortnightly. The "bar" was hardly more than a hole in the wall, and I should imagine that thirty people could just about cram in there, if necessary, yet it became the haunt of every class of society, from the humblest stoker and his missus to visiting diplomats and their ladies. Rumour had it that the patronage of a certain member of the Royal Family back in the late 40's had made it fashionable with the upper set ever after. During 1955 and 1956 my mates and I would occasionally drop in with the guitar for a sing-song, but apart from that there is no basis of fact in this ballad, which was composed during a spell of nostalgia after returning to U.K. They tell me it is no use looking for Sammy's bar now as it has disappeared under a road-widening scheme.

Stanley The Rat (1952)

My first ship was the large Fleet Carrier H.M.S. Indefatigable", and I joined her at Portland one evening in May 1952. Having travelled by train from Plymouth with my kitbag, hammock and toolbox, all I wanted to do on arrival was sleep. The other hands in the mess grinningly indicated a spare billet. I duly slung my hammock and not long after I clambered in a rat ran along the channel plating a few inches above my face. Now I knew why the billet was going spare. However, I soon got used to his nightly visits and christened him Stanley. Within days of joining the ship I had put together a little poem about his antics. Many years later I came across the Irish folk song "Brian O Lynn" and found that its tune fitted "Stanley" exactly.

Diesel And Shale (1958)

Service in Her Majesty's Submarines occupied a sizeable portion of my sea-time in the Navy, and this ballad was an attempt to chronicle those years. The circumstances under which I entered this elite branch revealed Admiralty hypocrisy at its most shameless. In the Spring of 1953 my mate Percy Whittle, being a newlywed and anxious to increase his income, volunteered for "boats" as we called them. A grand show was made of considering his application, and after undergoing the most thorough medical examination he was congratulated on being of a sufficiently high standard of fitness to be accepted into that select band of underwater heroes. In the Summer of that very same year a piece of paper arrived on board the "Indefatigable" at Portland bluntly informing me that I too would be joining submarines in the November, though I had never volunteered At my medical the doctor did not even produce a stethoscope, made no tests of any kind, asked me if I felt all right and proceeded to certify me as fit before I had a chance to answer! He had his instructions I suppose. Nevertheless, volunteer nr not, those years In submarines are good to look back on. In a very compressed period of time, I learned a lot about life, other people and myself, and that can't be bad for you. I discovered, for instance, that although diesel oil and shale oil produce the most clinging odour, when you all smell alike it doesn't seem to mailer.

My Mother Came From Norway (1958)

This little piece of punning nonsense will never threaten Edward Lear's reputation but it is nonetheless my only excursion into that field and I felt compelled to put it on record. Made up one dinner hour at H.M.S. "Collingwood", the Naval Electrical School at Fareham, Hants, in the Autumn of 1958

Six Feet Of Mud (1953)

Recalling the circumstances surrounding the germination of this song will always be a source of nostalgic pleasure for me. Imagine the Aircraft-Carrier "Indefatigable" riding in Portland Harbour. It is evening, and around the fire in the Electrical Artificers' Mess sit three hunched figures. National Serviceman Des Lockwood from Yorkshire (Where are you now?), Percy Whittle and myself. Each has his own individual reason for feeling as miserable as sin. Who starts it I can't remember, but a one-note dirge bewailing their lot begins to well up. It slowly expands until it actually resembles a tune, and a chorus takes shape which seems to have overtones of a sea-burial: —

"Six feet of mud, six feet of mud.

Five fathoms of water and six feet of mud."

There are a few abortive attempts at verses, but the only thing that really sticks is that chorus, a humble but authentic piece of communal creation. Before long the absurdity of this miserable psalm of self-pity strikes first one then another, until the glum faces crack and the singing dissolves into uncontrolled laughter, an example of song-therapy at its most effective.

Next day, on a long — weekend coach journey home to Gosport, I took the sea-burial idea and wrote a set of verses purporting to be sung by a dead body awaiting consignment to the deep. Five fathoms seemed far too shallow for such a ceremony so I deepened it to nine, scarcely more credible but with only one syllable to play with "twelve" is as deep as a songwriter can go anyway, so what the hell.

Ex-matelots will not need telling that Greenburgh's is a Naval tailor, a "green rub" is a raw deal, your "tiddley suit" is your best uniform, a "billet" is where you used to sling your hammock and to "do a sub" is to stand in for someone, normally used with reference to the duty watch.

In The Sidings (1963)

I learned this song from Louis Killen. Yes, that's what I said. It came about this way: During 1963 I had a regular spot as resident troubadour on Westward Television's magazine programme "Westward Diary". On the eve of the publication of the Beeching Report on British Railways the producer handed me an advance copy of the recommended axings in our area and asked if I could come up with a song for the following evening s show. Writing to order is not my cup of tea at all but I agreed to give it a go. In the end, though, I ignored the details of the paper and wrote about the proposals as seen through the eyes of one redundant old-timer, basing the idea loosely on the predicament of an acquaintance who ran Silverton Halt single-handed, a songwriter in his own right as it happened. I wasn't impressed with the result and, even worse, I just couldn't get the words into my head. The outcome the next evening was that most nightmarish of all experiences for the live performer, a mental "freeze" halfway through. I got myself over it rather clumsily and was consoled afterwards by Louis Killen who had watched rehearsals and the live transmission. Filled with disgust, I pushed the song right out of my mind, hoping everyone would forget it had ever happened. Imagine my horror when I learned that the producer had re-shown the whole studio discussion, with my "freeze" in the middle of it, a couple of days later. Asked for an explanation, he puffed at his pipe and said calmly "I couldn't care less about you really mate, it was the Beeching discussion that was important. " I relate the incident because it epitomizes the cavalier attitude towards the artist that prevails in the whizz-kid world of Current Affairs programmes.

Having said good riddance to the wretched song, or so I thought, I was quite taken aback to receive a request for it at a folk club up-country several months later. Only then did I realise that Louis had memorised it that day in Plymouth and had been putting it around. Thus it was that, driving down to Tyneside after we had completed a week at Edinburgh Palladium, L. Killen could be heard teaching C. Tawney his own song.

Five Foot Flirt (1950)

This mock-rustic ditty was written when I was ust turned twenty, which makes it the oldest song on the album. I was still an artificer apprentice and had become very involved in the shows we used to put on at end of term. About this time Rod Ingle's record "Cigareets and Whuskey" was all the rage and in a surge of national pride I felt constrained to come up with an English equivalent. A scratch group was planned called Sheep-dip Tawney and the Cowshed Cleaners, and "Five Foot Flirt" was specially written, but alas, no opportunity ever arose of staging the number before we were dispersed to various ships throughout the fleet. I didn't perform the song until I joined "Murray " at the end of 1957. While I was with that happy band of rascals we sang It guile a lot, lull when I left I dropped It again until I begun doing the folk club circuits in the 60's. It has been recorded by Adge Cutler and the Wurzels (what splendid Cowshed Cleaners they'd have made!), and by the Yetties themselves on their L.P. "Keep A runnin' — It's the Yetties!" (Argo ZFB 16),

On A Monday Morning (1962)

A song of self-pity, regret and remorse. Like their counterparts in the theatre, professional folk singers may occasionally resort to a temporary odd-job during a lean period. Thus, I found myself working as a labourer for a month at the Royal Naval Armament Depot. Plymouth in the summer of 1962. We had to clock in by seven every morning and this meant rising at an hour quite outlandish by my standards, the first morning after a convivial week-end in the bars of Plymouth being particularly hard to face, hence this song. It made its debut in October that year at a lunch-hour recital in a Leicester factory canteen during Arnold Wesker's Centre 42 experiment. Regrettably, one of the few failures of the English folk song revival has been that the average age of club audiences has remained at a consistent and puzzlingly low figure for over a decade, when ideally it should show a steady rise year by year. This becomes an important factor when a song of this type is being presented. While most of the audience maintain an air of sniggering detachment the faces of the few over-thirties in the room tell a much different story. Generations of cheap music-hall jokes about the liver haven't helped of course, but there were no smiles in the Leicester canteen that day. It happened to be Monday.

Nobby Hall (1960)

At one point in my R.N. service, between ships, they sent me on a course to learn the facts of life and death concerning various kinds of poison gas. One instructor obviously relished a particular cautionary tale about a matelot who used C.T.C. (Carbon Tetrachloride) as a cleaning fluid with fatal results. Its use for this purpose was unofficial, the real function being to refill fire extinguishers, but a blind eye was turned provided personnel were warned to perform the operation in a well-ventilated area. In ignoring this advice this sailor inadvertently brought about, not his own death, but that of his "oppo" or best friend. The tragic tale was related in an over-dramatic fashion, causing more amusement than shock, and some years later the memory of it gave rise to this song. The initials R.N.B.T. stand for Royal Naval Benevolent Trust.

Cheering The Queen (1958)

This one got me into the William Hickey column. Some people have dubbed it an anti-Royalty song, whereas anti-bull (or "flannel" as sailors call it) would be more accurate. After only three or four months on my first submarine, a leaky, shuddering twelve-year-old veteran of World War Two called "Trespasser", I found myself taking part in a sea-cavalcade with which the Admiralty intended to greet and impress their new young Queen as she returned up-Channel from her world tour. The rigid "Cheer Ship" drill is both necessary and attractive when applied to surface vessels, but to fifty or sixty submariners crammed shoulder-to-shoulder on the bridge of a T-boat it seemed pointless. Nevertheless, we rehearsed diligently, only to find at the critical moment that Mother Nature had decided to join in too. The song wasn't composed until early 1958, and the Hickey write-up occurred in the autumn, after I had been summoned to a Cecil Sharp House ball to sing it for Princess Margaret. She asked me for a copy of the words to give to "Britannia's" crew. I felt a bit daft as I had never written anything down, but we managed to get it typed out on the page of someone's grubby exercise book. She said "Thanks" and put it in her handbag. Then she said, "Now what about the tune?" It must have been then that I started thinking about a publisher.

New Names For Old (1968)

One of the sad facts of modern life is that the red-tape barrier between nations occasionally leads to that waste of time, money and energy known as a "marriage of convenience". A mate of mine once received such a proposition from a young American lady who had strong reasons for wishing to remain permanently in Britain, but he turned her down. I found myself wondering what might have happened had he been infatuated with her instead of indifferent, and I wove this imaginary tale in the autumn of 1968 during a week's singing tour of the Wye Valley. Oscar Brown Junior's excellent song "Rags and Old Iron" had a lot to do with the style I chose.

Chicken On A Raft (1958)

You will gather from these notes that for Tawney the songwriter 1958 was one of those inexplicably prolific years. My mind was scarcely ever on anything else but songs, and whatever small use I'd ever been to the Navy was rapidly diminishing. In addition to completed songs there were always several "on the stocks", many having progressed no further than a single four-line verse. In desperation I eventually decided upon a good old clear-out, and by introducing a special chorus I was able to string the stanzas together, shanty fashion. I never dreamed the song would reach the ears of civilians, consequently it's rather over-loaded with Navy jargon which would take the whole of this sleeve to explain, but as far as the chorus is concerned "Chicken on a raft" is a fried egg on a slice of fried bread, "dabtoes" are seamen and "dustmen" are stokers. The adoption of the song by The Young Tradition, one of the two most influential folk groups of the late 60's, breathed extra life into it and has even affected my own rendering.

The Grey Funnel Line (1959)

The last song I wrote in the Royal Navy. My final few months were spent in the Reserve Fleet at Devonport, attached to H.M.S. "Verulam". Louis Killen's brother Frank had put her in mothballs a few years earlier and I was bringing her back into service. The song, though, is a straightforward piece of nostalgia at leaving home and a loved one, the recurring last line "It's one more day on the Grey Funnel Line" making use of Jack's cynical "mercantile" nickname for the Royal Navy. Part of an American negro lament was pressed into service and adapted for the second half of verse two, while verse three was lost altogether for many years, due to my old habit of not writing anything down. Then at a Christmas party in 1964 I heard Louis Killen sing the song and congratulated him on the quality of the extra verse he had written. A grinning Killen replied, "I didn't write that, you did." Fortunately, he had taped me exactly five years earlier while the song was still fresh!

Well, that's it then. In conclusion I'd like to express my sincere thanks to all the singers who have helped to popularise these songs on both sides of the Atlantic. In particular Louis Killen, who was the first, Archie Fisher, who took up the torch in Scotland, Marianne Faithful, Carolyn Hester, Davy Graham, Alex Campbell, the Pentangle, the Young Tradition and the good old Yetties.