|

|

|

Sleeve Notes

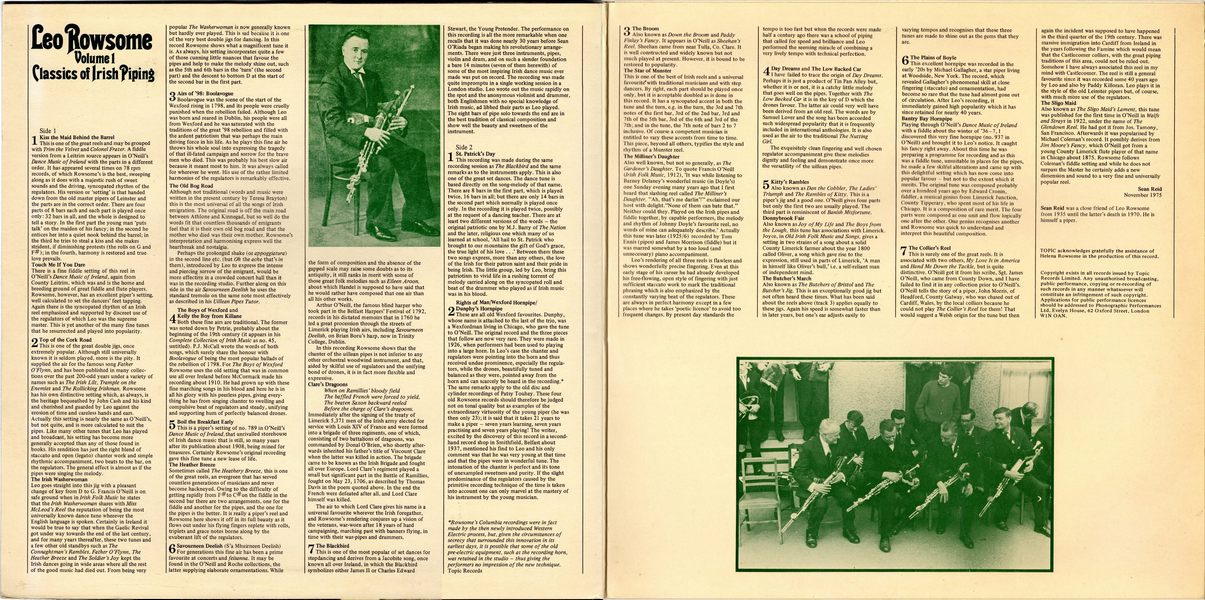

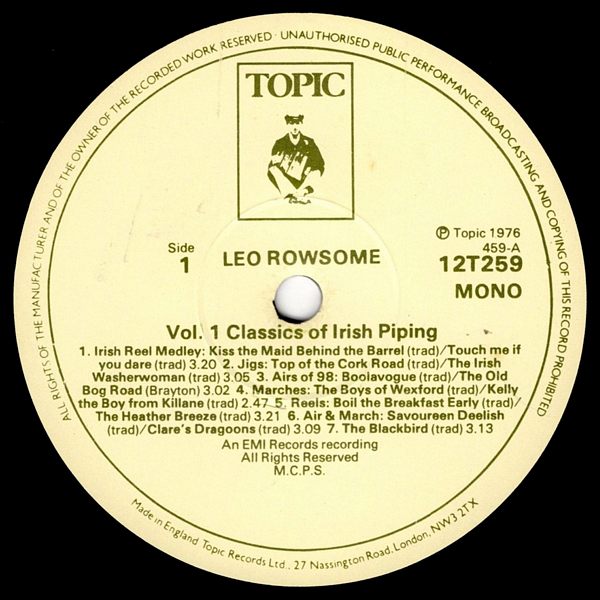

Kiss the Maid Behind the Barrel — This is one of the great reels and may be grouped with Trim the Velvet and Colonel Frazer. A fiddle version from a Leitrim source appears in O'Neill's Dance Music of Ireland with the parts in a different order. It has appeared several times on 78 rpm records, of which Rowsome's is the best, sweeping along as it does with a majestic rush of sweet sounds and the driving, syncopated rhythm of the regulators. His version or 'setting' is that handed down from the old master pipers of Leinster and the parts are in the correct order. There are four parts of 8 bars each and each part is played once only: 32 bars in all, and the whole is designed to tell a story. In the first part the young man 'puts talk' on the maiden of his fancy; in the second he entices her into a quiet nook behind the barrel; in the third he tries to steal a kiss and she makes strident, if diminishing protests (the rolls on G and F#); in the fourth, harmony is restored and true love prevails.

Touch Me If You Dare — There is a fine fiddle setting of this reel in O'Neill's Dance Music of Ireland, again from County Leitrim, which was and is the home and breeding ground of great fiddle and flute players. Rowsome, however, has an excellent piper's setting, well calculated to set the dancers' feet tapping. Again there is the syncopated rhythm of an Irish reel emphasized and supported by discreet use of the regulators of which Leo was the supreme master. This is yet another of the many fine tunes that he resurrected and played into popularity.

Top of the Cork Road — This is one of the great double jigs, once extremely popular. Although still universally known it is seldom played, more is the pity. It supplied the air for the famous song Father O'Flynn, and has been published in many collections over the past 200-odd years under a variety of names such as The Irish Lilt, Trample on the Enemies and The Rollicking Irishman. Rowsome has his own distinctive setting which, as always, is the heritage bequeathed by John Cash and his kind and cherished and guarded by Leo against the erosion of time and careless hands and ears. Actually this setting is nearly the same as O'Neill's, but not quite, and is more calculated to suit the pipes. Like many other tunes that Leo has played and broadcast, his setting has become more generally accepted than any of those found in books. His rendition has just the right blend of staccato and open (legato) chanter work and simple rhythmic accompaniment, two beats to the bar, on the regulators. The general effect is almost as if the pipes were singing the melody.

The Irish Washerwoman — Leo goes straight into this jig with a pleasant change of key from D to G. Francis O'Neill is on safe ground when in Irish Folk Music he states that the Irish Washerwoman shares with Miss McLeod's Reel the reputation of being the most universally known dance tune wherever the English language is spoken. Certainly in Ireland it would be true to say that when the Gaelic Revival got under way towards the end of the last century, and for many years thereafter, these two tunes and a few other old standbys such as The Connaghtman's Rambles, Father O'Flynn, The Heather Breeze and The Soldier's Joy kept the Irish dances going in wide areas where all the rest of the good music had died out. From being very popular The Washerwoman is now generally known but hardly ever played. This is sad because it is one of the very best double jigs for dancing. In this record Rowsome shows what a magnificent tune it is. As always, his setting incorporates quite a few of those cunning little nuances that favour the pipes and help to make the melody shine out, such as the 5th and 6th bars in the 'turn* (the second part) and the descent to bottom D at the start of the second bar in the first part.

Airs of '98: Boolavogue — Boolavogue was the scene of the start of the Wexford rising in 1798, and its people were cruelly punished when the rebellion failed. Although Leo was born and reared in Dublin, his people were all from Wexford and he was saturated with the traditions of the great '98 rebellion and filled with the ardent patriotism that was perhaps the main driving force in his life. As he plays this fine air he throws his whole soul into expressing the tragedy of that ill-fated campaign and sorrow for the brave men who died. This was probably his best slow air because it meant most to him. It was always called for wherever he went. His use of the rather limited harmonies of the regulators is remarkably effective.

The Old Bog Road — Although not traditional (words and music were written in the present century by Teresa Bray ton) this is the most universal of all the songs of Irish emigration. The original road is off the main road between Athlone and Kinnegad. but so well do the words fit that countless thousands of emigrants feel that it is their own old bog road and that the mother who died was their own mother. Rowsome's interpretation and harmonising express well the heartbreak and nostalgia.

Perhaps the prolonged shake (or appoggiatura) in the second line etc. (but Oh the ache that's in them), introduced by Leo to express the intense and piercing sorrow of the emigrant, would be more effective in a crowded concert hall than it was in the recording studio. Further along on this side in the air Savourneen Deelish he uses the standard tremolo on the same note most effectively as described in his Uillean Pipes Tutor.

The Boys of Wexford & Kelly the Boy from Killane — Both these fine airs are traditional. The former was noted down by Petrie, probably about the beginning of the 19th century (it appears in his Complete Collection of Irish Music as no. 45, untitled). P.J. McCall wrote the words of both songs, which surely share the honour with Boolavogue of being the most popular ballads of the rebellion of 1798. For The Boys of Wexford Rowsome uses the old setting that was in common use all over Ireland before McCormack made his recording about 1910. He had grown up with these fine marching songs in his blood and here he is in all his glory with his peerless pipes, giving everything he has from singing chanter to swelling and compulsive beat of regulators and steady, unifying and supporting hum of perfectly balanced drones.

Boil the Breakfast Early — This is a piper's setting of no. 789 in O'Neill's Dance Music of Ireland, that unrivalled storehouse of Irish dance music that is still, so many years after its publication about 1908, being mined for treasures. Certainly Rowsome's original recording gave this fine tune a new lease of life.

The Heather Breeze — Sometimes called The Heathery Breeze, this is one of the great reels, an evergreen that has served countless generations of musicians and never become hackneyed. Owing to the difficulty of getting rapidly from F# to C# on the fiddle in the second bar there are two arrangements, one for the fiddle and another for the pipes, and the one for the pipes is the better. It is really a piper's reel and Rowsome here shows it off in its full beauty as it flows out under his flying fingers replete with rolls, triplets and grace notes borne along by the exuberant lift of the regulators.

Savourneen Deelish (S'a Mhuirneen Deelish) — For generations this fine air has been a prime favourite at concerts and feisanna. It may be found in the O'Neill and Roche collections, the latter supplying elaborate ornamentations. While the form of composition and the absence of the gapped scale may raise some doubts as to its antiquity, it still ranks in merit with some of those great folk melodies such as Eileen Aroon, about which Handel is supposed to have said that he would rather have composed that one air than all his other works.

Arthur O'Neill, the famous blind harper who took part in the Belfast Harpers* Festival of 1792, records in his dictated memoirs that in 1760 he led a great procession through the streets of Limerick playing Irish airs, including Savourneen Deelish, on Brian Boru's harp, now in Trinity College, Dublin.

In this recording Rowsome shows that the chanter of the uillean pipes is not inferior to any other orchestral woodwind instrument, and that, aided by skilful use of regulators and the unifying bond of drones, it is in fact more flexible and expressive.

Clare's Dragoons

When on Ramillies' bloody field

The baffled French were forced to yield,

The beaten Saxon backward reeled

Before the charge of Clare's dragoons.

Immediately after the signing of the treaty of Limerick 5,371 men of the Irish army elected for service with Louis XIV of France and were formed into a brigade of three regiments, one of which, consisting of two battalions of dragoons, was commanded by Donal O'Brien, who shortly afterwards inherited his father's title of Viscount Clare when the latter was killed in action. The brigade came to be known as the Irish Brigade and fought all over Europe. Lord Clare's regiment played a small but significant part in the Battle of Ramillies, fought on May 23, 1706, as described by Thomas Davis in the poem quoted above. In the end the French were defeated after all, and Lord Clare himself was killed.

The air to which Lord Clare gives his name is a universal favourite wherever the Irish foregather, and Rowsome's rendering conjures up a vision of the veterans, war-worn after 18 years of hard campaigning, marching past with banners flying, in time with their war-pipes and drummers.

The Blackbird — This is one of the most popular of set dances for stepdancing and derives from a Jacobite song, once known all over Ireland, in which the Blackbird symbolizes either James II or Charles Edward Stewart, the Young Pretender. The performance on this recording is all the more remarkable when one recalls that it was done nearly 30 years before Sean O'Riada began making his revolutionary arrangements. There were just three instruments, pipes, violin and drum, and on such a slender foundation a bare 14 minutes (seven of them herewith) of some of the most inspiring Irish dance music ever made was put on record. The recording was made quite impromptu in a single working session in a London studio. Leo wrote out the music rapidly on the spot and the anonymous violinist and drummer, both Englishmen with no special knowledge of Irish music, ad libbed their parts as Leo played. The eight bars of pipe solo towards the end are in the best tradition of classical composition and show well the beauty and sweetness of the instrument.

St. Patrick's Day — This recording was made during the same recording session as The Blackbird and the same remarks as to the instruments apply. This is also one of the great set dances. The dance tune is based directly on the song-melody of that name. There are 8 bars in the First part, which is played twice, 16 bars in all; but there are only 14 bars in the second part which normally is played once only. In the recording it is played twice, possibly at the request of a dancing teacher. There are at least two different versions of the words — the original patriotic one by M.J. Barry of The Nation and the later, religious one which many of us learned at school, 'All hail to St. Patrick who brought to our mountains the gift of God's grace, the true light of his love . . .' Between them these two songs express, more than any others, the love of the Irish for their patron saint and their pride in being Irish. The little group, led by Leo, bring this patriotism to vivid life in a rushing torrent of melody carried along on the syncopated roll and beat of the drummer who played as if Irish music was in his blood.

Rights of Man, Wexford Hornpipe & Dunphy's Hornpipe — These are all old Wexford favourites. Dunphy, whose name is attached to the last of the trio, was a Wexfordman living in Chicago, who gave the tune to O'Neill. The original record and the three pieces that follow are now very rare. They were made in 1926, when performers had been used to playing into a large horn. In Leo's case the chanter and regulators were pointing into the horn and thus received undue prominence, especially the regulators, while the drones, beautifully tuned and balanced as they were, pointed away from the horn and can scarcely be heard in the recording.* The same remarks apply to the old disc and cylinder recordings of Patsy Touhey. These four old Rowsome records should therefore be judged not on tonal quality but as examples of the extraordinary virtuosity of the young piper (he was then only 23); it is said that it takes 21 years to make a piper — seven years learning, seven years practising and seven years playing! The writer, excited by the discovery of this record in a secondhand record shop in Smithfield, Belfast about 1937, mentioned his find to Leo and his only comment was that he was very young at that time and that the pipes were in wonderful tune. The intonation of the chanter is perfect and its tone of unexampled sweetness and purity. If the slight predominance of the regulators caused by the primitive recording technique of the time is taken into account one can only marvel at the mastery of his instrument by the young musician.

*Rowsome's Columbia recordings were in fact made by the then newly introduced Western Electric process, but, given the circumstances of secrecy that surrounded this innovation in its earliest days, it is possible that some of the old pre-electric equipment, such as the recording horn, was retained in the studio — thus giving the performers no impression of the new technique. Topic Records

The Broom — Also known as Down the Broom and Paddy Finlay's Fancy. It appears in O'Neill as Sheehan's Reel. Sheehan came from near Tulla, Co. Clare. It is well constructed and widely known but not much played at present. However, it is bound to be restored to popularity.

The Star of Munster — This is one of the best of Irish reels and a universal favourite with traditional musicians and with step dancers. By right, each part should be played once only, but it is acceptable doubled as is done in this record. It has a syncopated accent in both the tune and the turn, e.g. in the turn, the 3rd and 7th notes of the first bar, 3rd of the 2nd bar, 3rd and 7th of the 5th bar, 3rd of the 6th and 3rd of the 7th; and in the tune, the 7th note of bars 2 to 7 inclusive. Of course a competent musician is entitled to vary these accents from time to time. This piece, beyond all others, typifies the style and rhythm of a Munster reel.

The Milliner's Daughter — Also well known, but not so generally, as The Gardener's Daughter. To quote Francis O'Neill (Irish Folk Music, 1912), 'It was while listening to Barney Delaney's wonderful music (in Doyle's) one Sunday evening many years ago that I first heard that slashing reel called The Milliner's Daughter. “Ah, that's me darlin'!” exclaimed our host with delight. “None of them can bate that.” Neither could they. Played on the Irish pipes and fiddle together, by capable performers, the melody and rhythm of Johnny Doyle's favourite reel, no words of mine can adequately describe.' Actually this tune was later (1925/6) recorded by Tom Ennis (pipes) and James Morrison (fiddle) but it was marred somewhat by a too loud (and unnecessary) piano accompaniment.

Leo's rendering of all three reels is flawless and shows wonderfully precise fingering. Even at this early stage of his career he had already developed his free-flowing, open style of fingering with just sufficient staccato work to mark the traditional phrasing which is also emphasized by the constantly varying beat of the regulators. These are always in perfect harmony except in a few places where he takes 'poetic licence' to avoid too frequent changes. By present day standards the tempo is too fast but when the records were made half a century ago there was a school of piping that called for speed and brilliance and Leo performed the seeming miracle of combining a very lively tempo with technical perfection.

Day Dreams and The Low Backed Car — I have failed to trace the origin of Day Dreams. Perhaps it is just a product of Tin Pan Alley but, whether it is or not, it is a catchy little melody that goes well on the pipes. Together with The Low Backed Car it is in the key of D which the drones favour. The latter air could very well have been derived from an old reel. The words are by Samuel Lover and the song has been accorded such widespread popularity that it is frequently included in international anthologies. It is also used as the air to the traditional The Nutting Girl.

The exquisitely clean fingering and well chosen regulator accompaniment give these melodies dignity and feeling and demonstrate once more the versatility of the uillean pipes.

Kitty's Rambles — Also known as Dan the Cobbler, The Ladies' Triumph and The Rambles of Kitty. This is a piper's jig and a good one. O'Neill gives four parts but only the first two are usually played. The third part is reminiscent of Banish Misfortune.

Donnybrook Fair — Also known as Joy of My Life and The Boys from the Lough, this tune has associations with Limerick. Joyce, in Old Irish Folk Music and Songs, gives a setting in two strains of a song about a solid County Limerick farmer about the year 1800 called Oliver, a song which gave rise to the expression, still used in parts of Limerick, 'A man in himself like Oliver's bull,' i.e. a self-reliant man of independent mind.

The Butcher's March — Also known as The Butchers of Bristol and The Butcher's Jig. This is an exceptionally good jig but not often heard these times. What has been said about the reels above (track 3) applies equally to these jigs. Again his speed is somewhat faster than in later years, but one's ear adjusts easily to varying tempos and recognises that these three tunes are made to shine out as the gems that they are.

The Plains of Boyle — This excellent hornpipe was recorded in the early '20s by Michael Gallagher, a star piper living at Woodside, New York. The record, which revealed Gallagher's phenomenal skill at close fingering (staccato) and ornamentation, had become so rare that the tune had almost gone out of circulation. After Leo's recording, it immediately gained high popularity which it has since retained for nearly 40 years.

Bantry Bay Hornpipe — Playing through O'Neill's Dance Music of Ireland with a fiddle about the winter of '36-7, I discovered this very fine hornpipe (no. 937 in O'Neill) and brought it to Leo's notice. It caught his fancy right away. About this time he was preparing a programme for recording and as this was a fiddle tune, unsuitable in places for the pipes, he made a few skilful alterations and came up with this delightful setting which has now come into popular favour but not to the extent which it merits. The original tune was composed probably over a hundred years ago by Edward Cronin, fiddler, a musical genius from Limerick Junction, County Tipperary, who spent most of his life in Chicago. It is a composition of rare merit. The four parts were composed as one unit and flow logically one after the other. One genius recognises another and Rowsome was quick to understand and interpret this beautiful composition.

The Collier's Reel — This is surely one of the great reels. It is associated with two others, My Love Is in America and Hand Me Down the Tackle, but is quite distinctive. O'Neill got it from his scribe, Sgt. James O'Neill, who came from County Down, and I have failed to find it in any collection prior to O'Neill's. O'Neill tells the story of a piper, John Morris, of Headford, County Galway, who was chased out of Cardiff, Wales, by the local colliers because he could not play The Collier's Reel for them! That would suggest a Welsh origin for the tune but then again the incident was supposed to have happened in the third quarter of the 19th century. There was massive immigration into Cardiff from Ireland in the years following the Famine which would mean that the Castlecomer colliers, with the great piping traditions of this area, could not be ruled out. Somehow I have always associated this reel in my mind with Castlecomer. The reel is still a general favourite since it was recorded some 40 years ago by Leo and also by Paddy Killoran. Leo plays it in the style of the old Leinster pipers but, of course, with much more use of the regulators.

The Sligo Maid — Also known as The Sligo Maid's Lament, this tune was published for the first time in O'Neill in Waifs and Strays in 1922, under the name of The Glendown Reel. He had got it from Jos. Tamony, San Francisco. Afterwards it was popularised by Michael Coleman's record. It possibly derives from Jim Moore's Fancy, which O'Neill got from a young County Limerick flute player of that name in Chicago about 1875. Rowsome follows Coleman's fiddle setting and while he docs not surpass the Master he certainly adds a new dimension and sound to a very fine and universally popular reel.

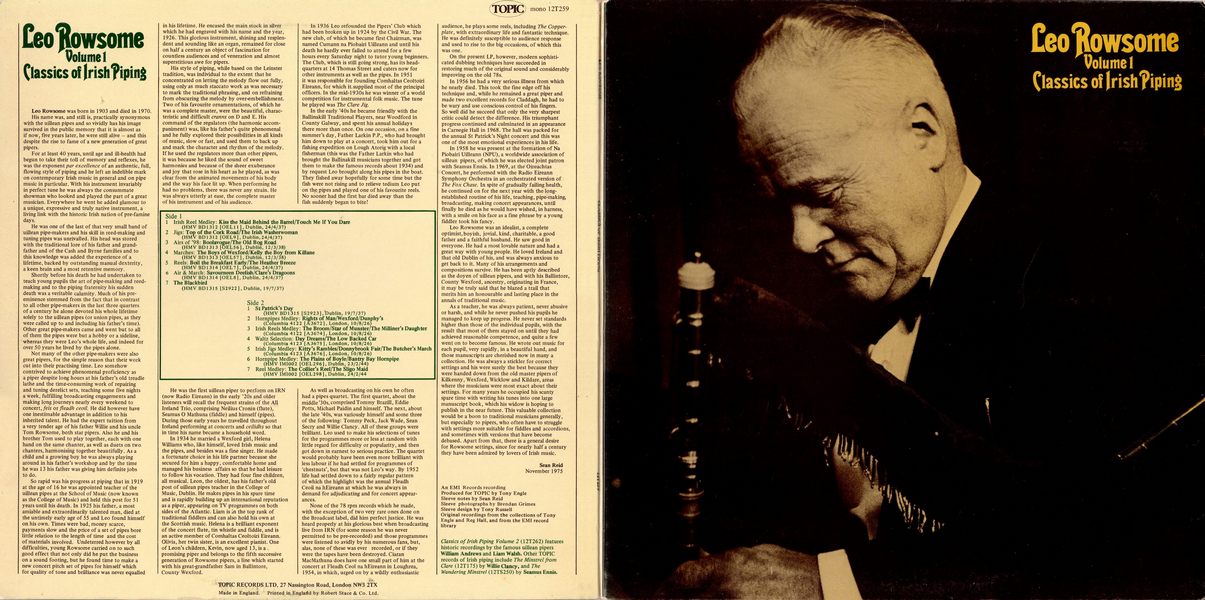

Leo Rowsome was born in 1903 and died in 1970.

His name was, and still is, practically synonymous with the uillean pipes and so vividly has his image survived in the public memory that it is almost as if now, five years later, he were still alive — and this despite the rise to fame of a new generation of great pipers.

For at least 40 years, until age and ill-health had begun to take their toll of memory and reflexes, he was the exponent par excellence of an authentic, full, flowing style of piping and he left an indelible mark on contemporary Irish music in general and on pipe music in particular. With his instrument invariably in perfect tune he was always the consummate showman who looked and played the part of a great musician. Everywhere he went he added glamour to a unique, expressive and truly native instrument, a living link with the historic Irish nation of pre-famine days.

He was one of the last of that very small band of uillean pipe-makers and his skill in reed-making and tuning pipes was unrivalled. His head was stored with the traditional lore of his father and grandfather and of the Cash and Byrne families and to this knowledge was added the experience of a lifetime, backed by outstanding manual dexterity, a keen brain and a most retentive memory.

Shortly before his death he had undertaken to teach young pupils the art of pipe-making and reedmaking and to the piping fraternity his sudden death was a veritable calamity. Much of his preeminence stemmed from the fact that in contrast to all other pipe-makers in the last three quarters of a century he alone devoted his whole lifetime solely to the uillean pipes (or union pipes, as they were called up to and including his father's time). Other great pipe-makers came and went but to all of them the pipes were but a hobby or a sideline, whereas they were Leo's whole life, and indeed for over 50 years he lived by the pipes alone.

Not many of the other pipe-makers were also great pipers, for the simple reason that their work cut into their practising time. Leo somehow contrived to achieve phenomenal proficiency as a piper despite long hours at his father's old treadle lathe and the time-consuming work of repairing and tuning derelict sets, teaching some five nights a week, fulfilling broadcasting engagements and making long journeys nearly every weekend to concert, feis or fleadh ceoil. He did however have one inestimable advantage in addition to his inherited talent. He had the expert tuition from a very tender age of his father Willie and his uncle Tom Rowsome, both star pipers. Also he and his brother Tom used to play together, each with one hand on the same chanter, as well as duets on two chanters, harmonising together beautifully. As a child and a growing boy he was always playing around in his father's workshop and by the time he was 13 his father was giving him definite jobs to do.

So rapid was his progress at piping that in 1919 at the age of 16 he was appointed teacher of the uillean pipes at the School of Music (now known as the College of Music) and held this post for 51 years until his death. In 1925 his father, a most amiable and extraordinarily talented man, died at the untimely early age of 55 and Leo found himself on his own. Times were bad, money scarce, payments slow and the price of a set of pipes bore little relation to the length of time and the cost of materials involved. Undeterred however by all difficulties, young Rowsome carried on to such good effect that not only did he put the business on a sound footing, but he found time to make a new concert pitch set of pipes for himself which for quality of tone and brilliance was never equalled in his lifetime. He encased the main stock in silver which he had engraved with his name and the year, 1926. This glorious instrument, shining and resplendent and sounding like an organ, remained for close on half a century an object of fascination for countless audiences and of veneration and almost superstitious awe for pipers.

His style of piping, while based on the Leinster tradition, was individual to the extent that he concentrated on letting the melody flow out fully, using only as much staccato work as was necessary to mark the traditional phrasing, and on refraining from obscuring the melody by over-embellishment. Two of his favourite ornamentations, of which he was a complete master, were the beautiful, characteristic and difficult cranns on D and E. His command of the regulators (the harmonic accompaniment) was, like his father's quite phenomenal and he fully explored their possibilities in all kinds of music, slow or fast, and used them to back up and mark the character and rhythm of the melody. If he used the regulators more than other pipers, it was because he liked the sound of sweet harmonies and because of the sheer exuberance and joy that rose in his heart as he played, as was clear from the animated movements of his body and the way his face lit up. When performing he had no problems, there was never any strain. He was always utterly at ease, the complete master of his instrument and of his audience. He was the first uillean piper to perform on IRN (now Radio Eireann) in the early '20s and older listeners will recall the frequent strains of the All Ireland Trio, comprising Neilius Cronin (flute), Seamus O Mathuna (fiddle) and himself (pipes). During those early years he travelled throughout Ireland performing at concerts and ceilidhs so that in time his name became a household word.

In 1934 he married a Wexford girl, Helena Williams who, like himself, loved Irish music and the pipes, and besides was a fine singer. He made a fortunate choice in his life partner because she secured for him a happy, comfortable home and managed his business affairs so that he had leisure to follow his vocation. They had four fine children, all musical. Leon, the oldest, has his father's old post of uillean pipes teacher in the College of Music, Dublin. He makes pipes in his spare time and is rapidly building up an international reputation as a piper, appearing on TV programmes on both sides of the Atlantic. Liam is in the top rank of traditional fiddlers and can also hold his own at the Scottish music. Helena is a brilliant exponent of the concert flute, tin whistle and fiddle, and is an active member of Comhaltas Ceoltoiri Eireann. Olivia, her twin sister, is an excellent pianist. One of Leon's children, Kevin, now aged 13, is a.. promising piper and belongs to the fifth successive generation of Rowsome pipers, a line which started with his great-grandfather Sam in Ballintore, County Wexford.

In 1936 Leo refounded the Pipers' Club which had been broken up in 1924 by the Civil War. The new club, of which he became first Chairman, was named Cumann na Piobairi Uilleann and until his death he hardly ever failed to attend for a few hours every Saturday night to tutor young beginners. The Club, which is still going strong, has its headquarters at 14 Thomas Street and caters now for other instruments as well as the pipes. In 1951 it was responsible for founding Comhaltas Ceoltoiri Eireann, for which it supplied most of the principal officers. In the mid-1930s he was winner of a world competition for instrumental folk music. The tune he played was The Clare Jig.

In the early '40s he became friendly with the Ballinakill Traditional Players, near Woodford in County Galway, and spent his annual holidays there more than once. On one occasion, on a fine summer's day, Father Larkin P.P., who had brought him down to play at a concert, took him out for a fishing expedition on Lough Atorig with a local fisherman (this was the Father Larkin who had brought the Ballinakill musicians together and got them to make the famous records about 1934) and by request Leo brought along his pipes in the boat. They fished away hopefully for some time but the fish were not rising and to relieve tedium Leo put on the pipes and played one of his favourite reels.

No sooner had the first bar died away than the fish suddenly began to bite!

As well as broadcasting on his own he often had a pipes quartet. The first quartet, about the middle '30s, comprised Tommy Brazill, Eddie Potts, Michael Paidin and himself. The next, about the late '40s, was variously himself and some three of the following: Tommy Peck, Jack Wade, Sean Secry and Willie Clancy. All of these groups were brilliant. Leo used to make his selections of tunes for the programmes more or less at random with little regard for difficulty or popularity, and then got down in earnest to serious practice. The quartet would probably have been even more brilliant with less labour if he had settled for programmes of 'chestnuts', but that was not Leo's way. By 1952 life had settled down to a fairly regular pattern of which the highlight was the annual Fleadh Ceoil na hEireann at which he was always in demand for adjudicating and for concert appearances.

None of the 78 rpm records which he made, with the exception of two very rare ones done on the Broadcast label, did him perfect justice. He was heard properly at his glorious best when broadcasting live from IRN (for some reason he was never permitted to be pre-recorded) and those programmes were listened to avidly by his numerous fans, but, alas, none of these was ever recorded, or if they were the tapes have been destroyed. Ciaran MacMathuna does have one small part of him at the concert at Fleadh Ceol na hEireann in Loughrea, 1954, in which, urged on by a wildly enthusiastic audience, he plays some reels, including The Copperplate, with extraordinary life and fantastic technique. He was definitely susceptible to audience response and used to rise to the big occasions, of which this was one.

On the present LP, however, modern sophisticated dubbing techniques have succeeded in restoring much of the original sound and considerably improving on the old 78s.

In 1956 he had a very serious illness from which he nearly died. This took the fine edge off his technique and, while he remained a great piper and made two excellent records for Claddagh, he had to be wary and use conscious control of his fingers.

So well did he succeed that only the very sharpest critic could detect the difference. His triumphant progress continued and culminated in an appearance in Carnegie Hall in 1968. The hall was packed for the annual St Patrick's Night concert and this was one of the most emotional experiences in his life.

In 1958 he was present at the formation of Na Piobairi Uilleann (NPU), a worldwide association of uillean pipers, of which he was elected joint patron with Seamus Ennis. In 1969, at the Oireachtas Concert, he performed with the Radio Eireann Symphony Orchestra in an orchestrated version of The Fox Chase. In spite of gradually failing health, he continued on for the next year with the long-established routine of his life, teaching, pipe-making, broadcasting, making concert appearances, until finally he died as he would have wished, in harness, with a smile on his face as a fine phrase by a young fiddler took his fancy.

Leo Rowsome was an idealist, a complete optimist, boyish, jovial, kind, charitable, a good father and a faithful husband. He saw good in everyone. He had a most lovable nature and had a great way with young people. He loved Ireland and that old Dublin of his, and was always anxious to get back to it. Many of his arrangements and compositions survive. He has been aptly described as the doyen of uillean pipers, and with his Ballintore, County Wexford, ancestry, originating in France, it may be truly said that he blazed a trail that merits him an honourable and lasting place in the annals of traditional music.

As a teacher, he was always patient, never abusive or harsh, and while he never pushed his pupils he managed to keep up progress. He never set standards higher than those of the individual pupils, with the result that most of them stayed on until they had achieved reasonable competence, and quite a few went on to become famous. He wrote out music for each pupil, very rapidly, in a beautiful hand, and those manuscripts are cherished now in many a collection. He was always a stickler for correct settings and his were surely the best because they were handed down from the old master pipers of Kilkenny, Wexford, Wicklow and Kildare, areas where the musicians were most exact about their settings. For many years he occupied his scanty spare time with writing his tunes into one large manuscript book, which his widow is hoping to publish in the near future. This valuable collection would be a boon to traditional musicians generally, but especially to pipers, who often have to struggle with settings more suitable for fiddles and accordions, and sometimes with versions that have become debased. Apart from that, there is a general desire for Rowsome settings, since for nearly half a century they have been admired by lovers of Irish music.

Sean Reid

November 1975

Sean Reid was a close friend of Leo Rowsome from 1935 until the latter's death in 1970. He is himself a piper.

TOPIC acknowledges gratefully the assistance of Helena Rowsome in the production of this record.