|

|

|

|

Sleeve Notes

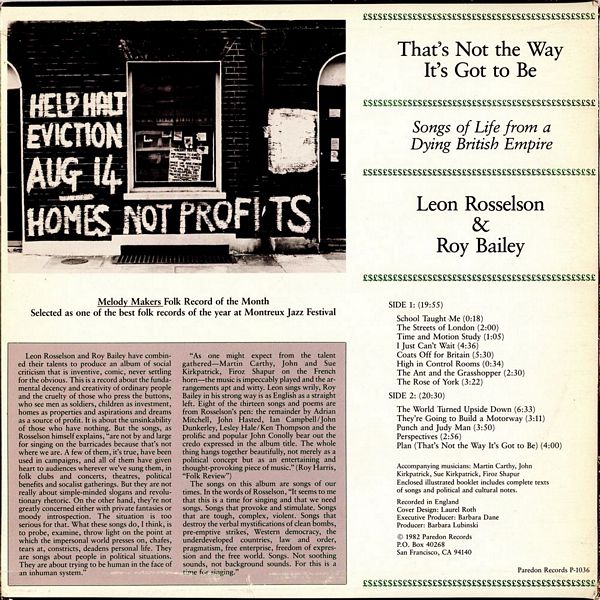

Leon Rosselson and Roy Bailey have combined their talents to produce an album of social criticism that is inventive, comic, never settling for the obvious. This a record about the fundamental decency and creativity of ordinary people and the cruelty of those who press the buttons, who see men as soldiers, children as investment, homes as properties and aspirations and dreams as a source of profit. It is about the unsinkability of those who have nothing. But the songs, as Rosselson himself explains, "are not by and large for singing on the barricades because that's not where we are. A few of them, it's true, have been used in campaigns, and all of them have given heart to audiences wherever we've sung them, in folk clubs and concerts, theatres, political benefits and socalist gatherings. But they are not really about simple-minded slogans and revolutionary rhetoric. On the other hand, they're not greatly concerned either with private fantasies or moody introspection. The situation is too serious for that. What these songs do, I think, is to probe, examine, throw light on the point at which the impersonal world presses on, chafes, tears at, constricts, deadens personal life. They are songs about people in political situations. They are about trying to be human in the face of an inhuman system."

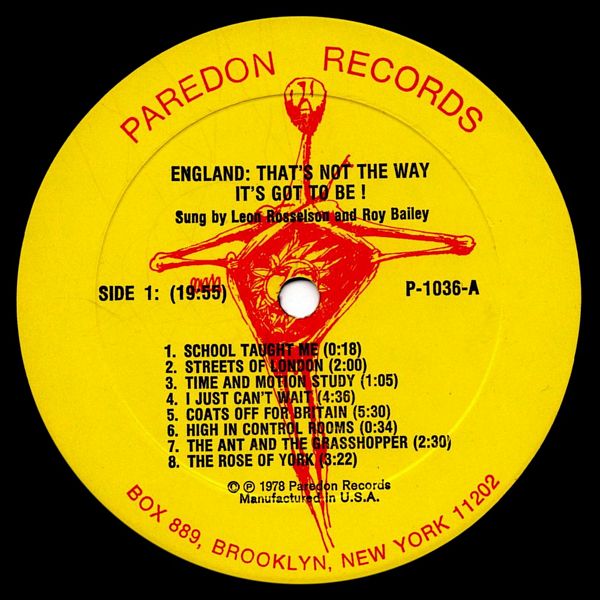

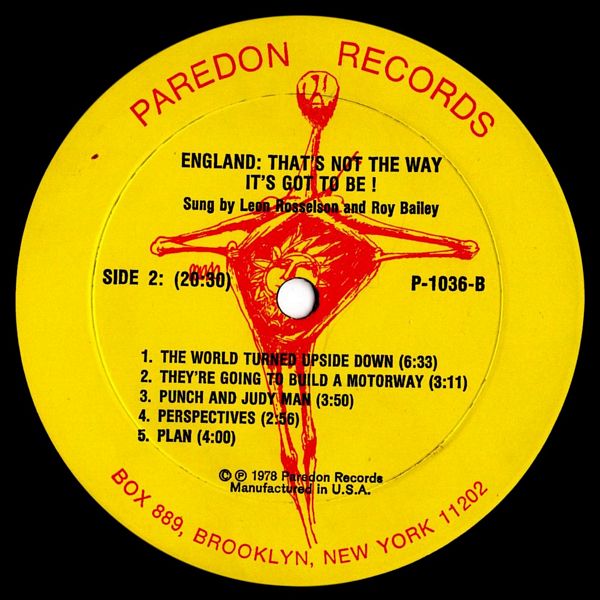

"As one might expect from the talent gathered — Martin Carthy, John and Sue Kirkpatrick, Firoz Shapur on the French horn — the music is impeccably played and the arrangements apt and witty. Leon sings wrily, Roy Bailey in his strong way is as English as a straight left. Eight of the thirteen songs and poems are from Rosselson's pen: the remainder by Adrian Mitchell, John Hasted, Ian Campbell/John Dunkerley, Lesley Hale/Ken Thompson and the prolific and popular John Conolly bear out the credo expressed in the album title. The whole thing hangs together beautifully, not merely as a political concept but as an entertaining and thought-provoking piece of music." (Roy Harris, "Folk Review") The songs on this album are songs of our times. In the words of Rosselson, "It seems to me that this a time for singing and that we need songs. Songs that provoke and stimulate. Songs that are tough, complex, violent. Songs that destroy the verbal mystifications of clean bombs, pre-emptive strikes, Western democracy, the underdeveloped countries, law and order, pragmatism, free enterprise, freedom of expression and the free world. Songs. Not soothing sounds, not background sounds. For this a time for singing."

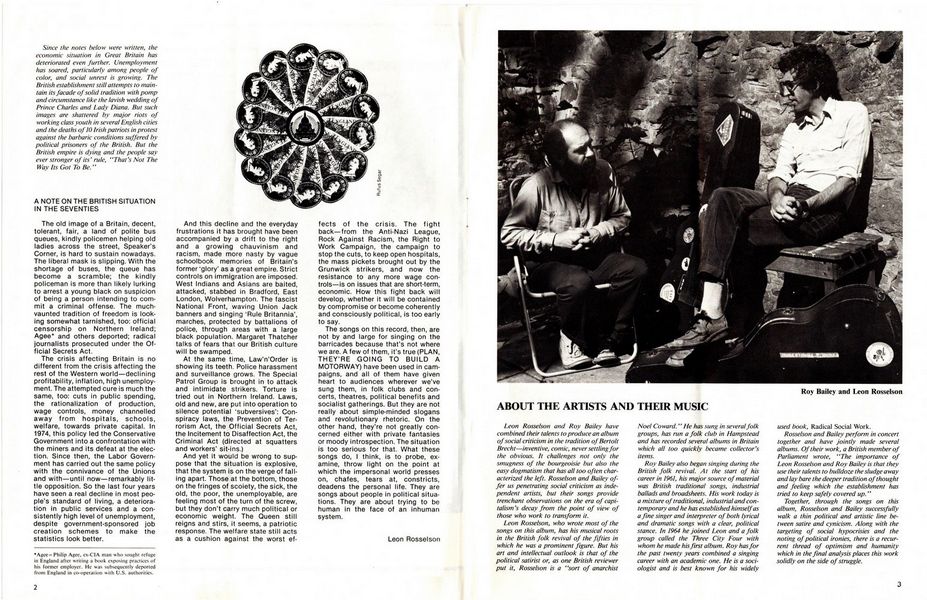

ABOUT THE ARTISTS AND THEIR MUSIC

Leon Rosselson and Roy Bailey have combined their talents to produce an album of social criticism in the tradition of Bertolt Brecht — inventive, comic, never settling for the obvious. It challenges not only the smugness of the bourgeoisie but also the easy dogmatism that has all too often characterized the left. Rosselson and Bailey offer us penetrating social criticism as independent artists, but their songs provide trenchant observations on the era of capitalism's decay from the point of view of those who work to transform it.

Leon Rosselson, who wrote most of the songs on this album, has his musical roots in the British folk revival of the fifties in which he was a prominent figure. But his art and intellectual outlook is that of the political satirist or, as one British reviewer put it, Rosselson is a "sort of anarchist Noel Coward." He has sung in several folk groups, has run a folk club in Hampstead and has recorded several albums in Britain which all too quickly became collector's items.

Roy Bailey also began singing during the British folk revival. At the start of his career in 1961, his major source of material was British traditional songs, industrial ballads and broadsheets. His work today is a mixture of traditional, industrial and contemporary and he has established himself as a fine singer and interpreter of both lyrical and dramatic songs with a clear, political stance. In 1964 he joined Leon and a folk group called the Three City Four with whom he made his first album. Roy has for the past twenty years combined a singing career with an academic one. He is a sociologist and is best known for his widely used book, Radical Social Work.

Rosselson and Bailey perform in concert together and have jointly made several albums. Of their work, a British member of Parliament wrote, "The importance of Leon Rosselson and Roy Bailey is that they use their talents to bulldoze the sludge away and lay bare the deeper tradition of thought and feeling which the establishment has tried to keep safely covered up."

Together, through the songs on this album, Rosselson and Bailey successfully walk a thin political and artistic line between satire and cynicism. Along with the targeting of social hypocrisies and the noting of political ironies, there is a recurrent thread of optimism and humanity which in the final analysis places this work solidly on the side of struggle.

ABOUT THE SONGS

It is always useful to remind the pundits who tell you Britain is too conservative ever to have a revolution that three centuries ago the people of Britain rose and executed their own king for treason. Although, inevitably at that time, it was the merchants and money-lenders who came to the top, to the common people for a few years everything seemed possible. Through the prolific pamphlet literature of the Civil War runs a recurring phrase, borrowed from an episode in the Bible: the world was going to be turned upside down.

THE WORLD TURNED UPSIDE DOWN is the key song on this record. It is constructed largely of the fine and vivid phrases of Gerrard Winstanley, spokesman for the handful of poor people who in 1649 on St. George's Hill in Surrey, inspired by a vision of the earth as a common treasury, tried to make a reality of the commonwealth of mankind. It puts better than a dozen history lessons the relevance of the past to the present. Like everything else on this record, it is a song for today.

What this record is about is the fundamental decency and creativity of ordinary people and the cruelty of those who press the buttons, who see men as soldiers, children as an investment, homes as properties and aspirations and dreams as a source of profit. It is about the un-sinkability of those who have nothing. It is about a society in which there are those who expect only obedience — whether the orders are to die for king and country, to work harder for the national interest or to hail progress in the form of slot machines and motorways — and those who are expected only to obey. It is about a world in which the industrious self-made ant is held up as an example to us all.

But consider the poets and songmakers who say he's a selfish bastard, as Rosselson does in his version of the fable and as Adrian Mitchell does in TIME AND MOTION STUDY. The protagonist of TIME AND MOTION STUDY would regard the protagonist of I JUST CAN'T WAIT or THEY'RE GOING TO BUILD A MOTORWAY as a solid achievement — a man who recognizes that he can't hit back, who acknowledges that those in authority know what they're doing and do it for the common good. He would regard the working man in COATS OFF FOR BRITAIN as a bit of a red, too idle or too obstinate to respond to Harold Heath's appeals to make more profits for someone else in the national interest. But above all he fears the initiative of the young boy in PERSPECTIVES, the nostalgia of those who groan when they see the Wombles* and remember the PUNCH AND JUDY MAN, the pride of the working man whose boast is that he has never been a blackleg*, and most of all the enduring vision of the Diggers. If all those people were isolated idealists it might not matter to the world's ants; but the ants know what the Digger's contemporary John Warr knew:

"There are some sparks of freedom in the minds of most, which ordinarily lie deep and are covered in the dark as a spark in the ashes."

These are the people who have it in their power to turn the world upside down once they decide THAT'S NOT THE WAY IT'S GOT TO BE.

Stephen Sedley

* Wombles = puppets (like muppets or Sesame Street character) from a popular children's show called "The Wombles of Wimbledon."

* blackleg = scab; strikebreaker

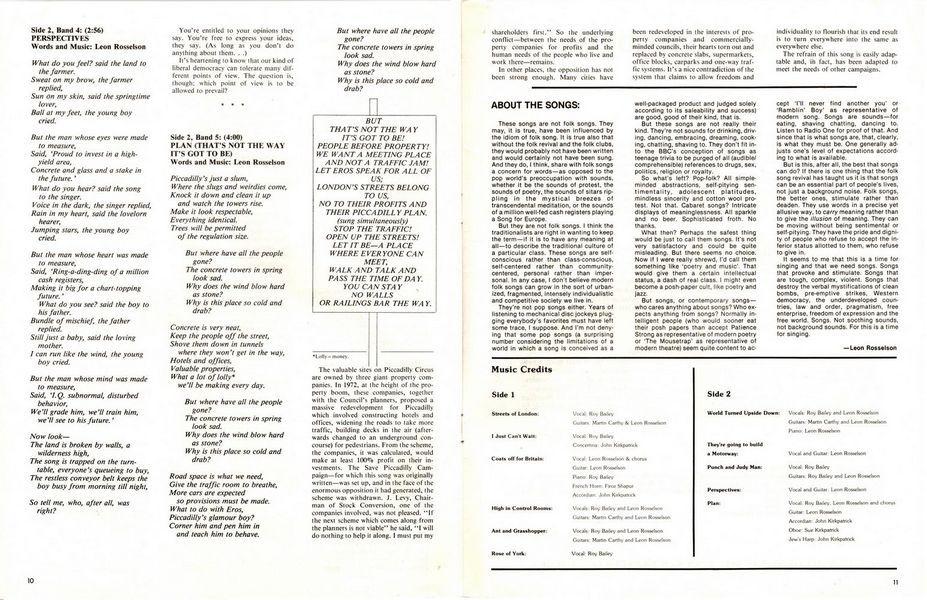

ABOUT THE SONGS

These songs are not folk songs. They may, It is true, have been influenced by the idiom of folk song. It is true also that without the folk revival and the folk clubs, they would probably not have been written and would certainly not have been sung. And they do, I think, share with folk songs a concern for words — as opposed to the pop world's preoccupation with sounds, whether it be the sounds of protest, the sounds of poetry, the sounds of sitars rippling in the mystical breezes of transcendental meditation, or the sounds of a million well-fed cash registers playing a Song for Europe.

But they are not folk songs. I think the traditionalists are right in wanting to keep the term — if it is to have any meaning at all — to describe the traditional culture of a particular class. These songs are self-conscious rather than class-conscious, self-centered rather than community-centered, personal rather than impersonal. In any case, I don't believe modern folk songs can grow in the sort of urbanized, fragmented, intensely individualistic and competitive society we live in.

They're not pop songs either. Years of listening to mechanical disc jockeys plugging everybody's favorites must have left some trace, I suppose. And I'm not denying that some pop songs (a surprising number considering the limitations of a world in which a song is conceived as a well-packaged product and judged solely according to its saleability and success) are good, good of their kind, that is.

But these songs are not really their kind. They're not sounds for drinking, driving, dancing, embracing, dreaming, cooking, chatting, shaving to. They don't fit into the BBC's conception of songs as teenage trivia to be purged of all (audible/ comprehensible) references to drugs, sex, politics, religion or royalty.

So what's left? Pop-folk? All simple-minded abstractions, self-pitying sentimentality, adolescent platitudes, mindless sincerity and cotton wool protest. Not that. Cabaret songs? Intricate displays of meaninglessness. All sparkle and no beer. Sophisticated froth. No thanks.

What then? Perhaps the safest thing would be just to call them songs. It's not very satisfactory and could be quite misleading. But there seems no choice. Now if I were really shrewd, I'd call them something like 'poetry and music'. That would give them a certain intellectual status, a dash of real class. I might even become a posh-paper cult, like poetry and jazz.

But songs, or contemporary songs — who cares anything about songs? Who expects anything from songs? Normally intelligent people (who would sooner eat their posh papers than accept Patience Strong as representative of modern poetry or The Mousetrap' as representative of modern theatre) seem quite content to accept 'I'll never find another you' or 'Ramblin' Boy' as representative of modern song. Songs are sounds — for eating, shaving chatting, dancing to. Listen to Radio One for proof of that. And since that is what songs are, that, clearly, is what they must be. One generally adjusts one's level of expectations according to what is available.

But is this, after all, the best that songs can do? If there is one thing that the folk song revival has taught us it is that songs can be an essential part of people's lives, not just a background noise. Folk songs, the better ones, stimulate rather than deaden. They use words in a precise yet allusive way, to carry meaning rather than to give the illusion of meaning. They can be moving without being sentimental or self-pitying. They have the pride and dignity of people who refuse to accept the inferior status allotted to them, who refuse to give in.

It seems to me that this a time for singing and that we need songs. Songs that provoke and stimulate. Songs that are tough, complex, violent. Songs that destroy the verbal mystifications of clean bombs, pre-emptive strikes, Western democracy, the underdeveloped countries, law and order, pragmatism, free enterprise, freedom of expression and the free world. Songs. Not soothing sounds, not background sounds. For this a time for singing.

— Leon Rosselson