|

|

|

| more images |

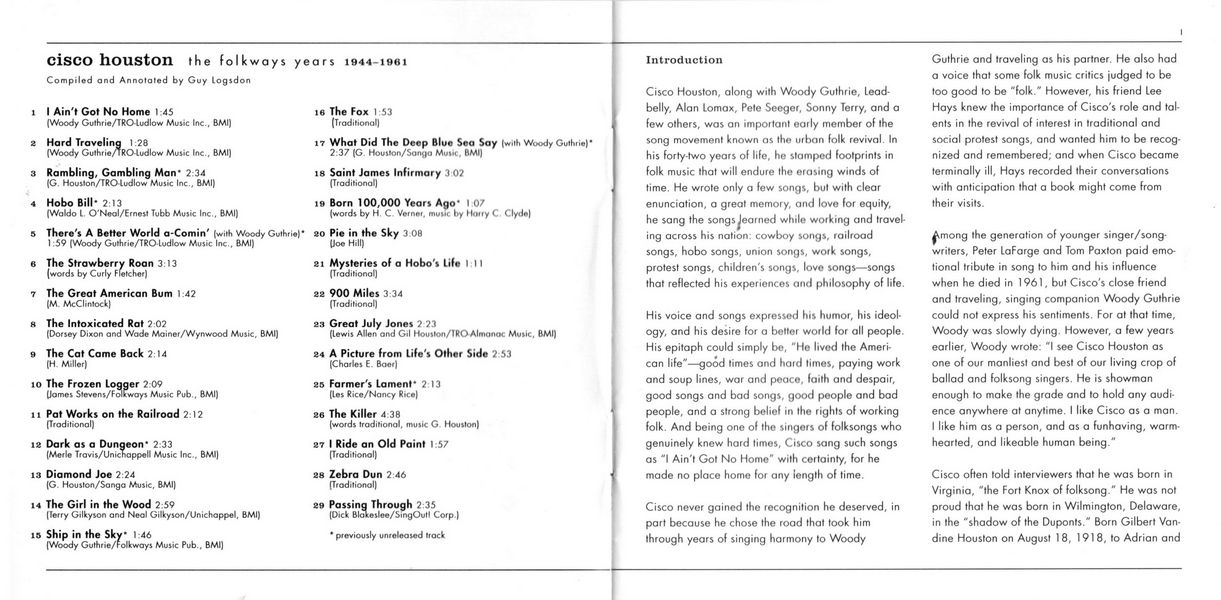

Introduction

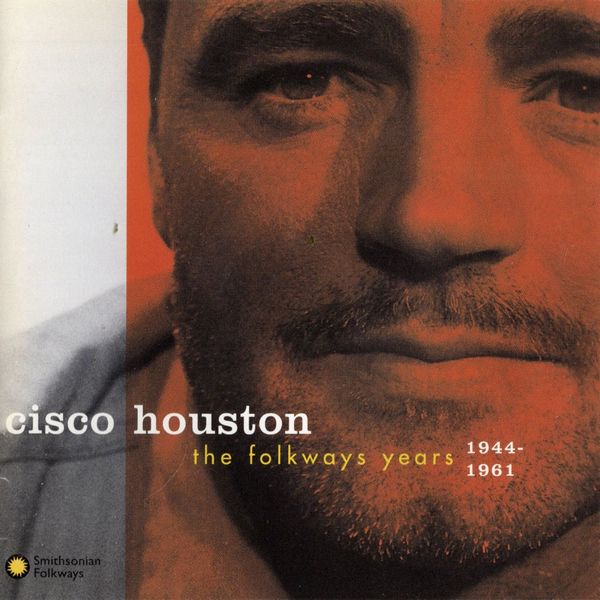

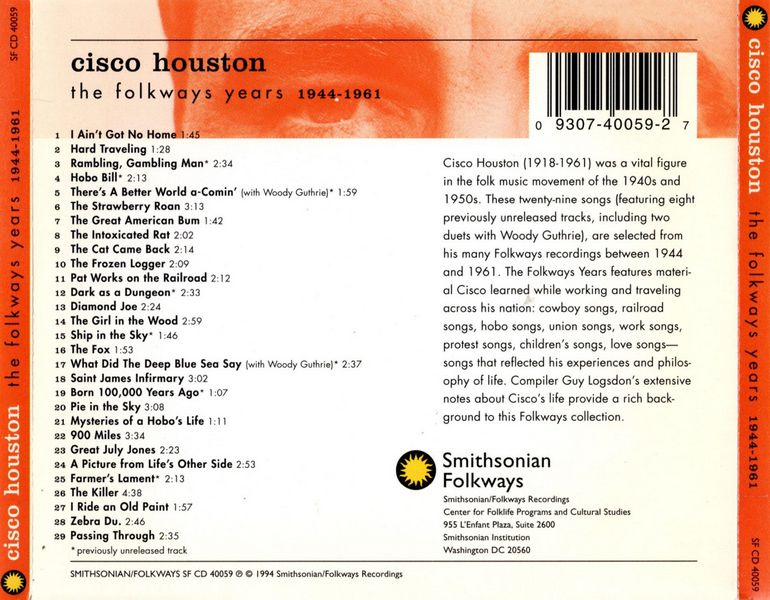

Cisco Houston, along with Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Alan Lomax, Pete Seeger, Sonny Terry, and a few others, was an important early member of the song movement known as the urban folk revival. In his forty-two years of life, he stamped footprints in folk music that will endure the erasing winds of time. He wrote only a few songs, but with clear enunciation, a great memory, and love for equity, he sang the songs learned while working and traveling across his nation: cowboy songs, railroad songs, hobo songs, union songs, work songs, protest songs, children's songs, love songs — songs that reflected his experiences and philosophy of life.

His voice and songs expressed his humor, his ideology, and his desire for a better world for all people. His epitaph could simply be, "He lived the American life" — good times and hard times, paying work and soup lines, war and peace, faith and despair, good songs and bad songs, good people and bad people, and a strong belief in the rights of working folk. And being one of the singers of folksongs who genuinely knew hard times, Cisco sang such songs as "I Ain't Got No Home" with certainty, for he made no place home for any length of time.

Cisco never gained the recognition he deserved, in part because he chose the road that took him through years of singing harmony to Woody Guthrie and traveling as his partner. He also had a voice that some folk music critics judged to be too good to be "folk." However, his friend Lee Hays knew the importance of Cisco's role and talents in the revival of interest in traditional and social protest songs, and wanted him to be recognized and remembered; and when Cisco became terminally ill, Hays recorded their conversations with anticipation that a book might come from their visits.

Among the generation of younger singer/songwriters, Peter LaFarge and Tom Paxton paid emotional tribute in song to him and his influence when he died in 1961, but Cisco's close friend and traveling, singing companion Woody Guthrie could not express his sentiments. For at that time, Woody was slowly dying. However, a few years earlier, Woody wrote: "I see Cisco Houston as one of our manliest and best of our living crop of ballad and folksong singers. He is showman enough to make the grade and to hold any audience anywhere at anytime. I like Cisco as a man. I like him as a person, and as a funhaving, warmhearted, and likeable human being."

Cisco often told interviewers that he was born in Virginia, "the Fort Knox of folksong." He was not proud that he was born in Wilmington, Delaware, in the "shadow of the Duponts." Born Gilbert Vandine Houston on August 18, 1918, to Adrian and Mary Houston, he was the second of their four children. Adrian was a sheet-metal worker with strong roots in North Carolina traditions; Mary and her mother carried songs and traditions from their heritage in Virginia, a heritage that gave Cisco much pride and for many years made him call Virginia his birthplace. He grew up hearing his mother and grandmother sing their traditional songs.

When he was two years old, the family moved to California, where Cisco attended school in Eagle Rock Valley, which lies between Pasadena and Glendale. His teachers considered him to be intelligent, but did not understand why he relied on memory instead of reading ability. They never knew that Gilbert, or Gil as he was known in family circles and among childhood friends, was nearly blind; he had nystagmus, a disease that obliterates all vision except peripheral sight. He became so good at covering this dilemma that many friends in his folk music circles did not know about his vision problems. Moses Asch, his friend and Folkways Records producer, said, "He wanted to be an actor; they had to put a big cross where he was to stand, and he couldn't even see it. He had no eyesight, was blind as a bat, and could never be what he wanted" (Asch-Logsdon interview). Asch noticed that when Cisco read lyrics, he turned his head as if he were glancing at the words out of the corner of his eye. Cisco could read, but only by slanting his head or reading at an oblique angle; his reliance on memory developed skills to learn songs quickly.

His recollections about his early life were:

"My schooling began at Rockdale Elementary [Eagle Rock Valley], It was here that I first gained some prominence as singer, actor, and artist. I was commissioned to draw the posters for school productions, managed to be cast in leading parts, and was encouraged to follow a career of singing by 'perceptive' teachers. I remember singing Brahms' 'Lullaby' in 'Hansel and Gretel' in the fourth grade. I was cast as the angel — a colossal bit of miscasting, according to my mother. Junior high and senior high years were spent at Eagle Rock High. [He did not graduate from high school.] By this time I knew clearly what I wanted to do; it was to be acting and singing folk songs, and anything else I had to do in between to make this possible was okay with me. My acting started with courses at Los Angeles City College and other night classes; experience came at little theater groups in Hollywood and Pasadena Playhouse. My career as a folksinger started when I met up with Woody Guthrie." ("Autobiographical Notes by Cisco Houston" in the Cisco Houston Papers, Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies Archive, Smithsonian Institution.)

He left much of his experience out of the foregoing statement. In 1930, the year after the Great Depression started, the family moved to Bakersfield. There, he and his older brother assumed some of the responsibilities of bringing money and food home, for in 1932, his father deserted the family. Cisco recalled:

"We were on relief for a while; that was a miserable deal. A lot of us kids used to go out on trucks and work in the rhubarb fields and truck farms, and in return for so many hours of work we would get some milk and vegetables."

"Oranges were cheap then. You could get a big bag for a quarter, if you had a quarter. But even then there was a big surplus, and they'd dig big long trenches and dump oranges in them, truck loads, millions of oranges. People would go out and help themselves before the fruit rotted. To prevent that, they dumped creosote in the trenches so the people couldn't eat them."

"I have seen mountains of potatoes with kerosene poured over them at a time when people were hungry and many were literally starving. It is hard to believe that anyone would do anything as wicked as that, even to work up some kind of subsidy for the farmers."

"When Boy [his older brother] and I were sixteen or seventeen, we started to wander around the country looking for work, in order to help out. I went up to Washington once and worked in the hop fields around Yakima. I hitchhiked, and rode freight trains, and walked the highways between jobs. I left there with twelve dollars. I nursed that money all the way home. I even managed to increase it. People would feel sorry for this young fellow standing on the road, and they'd give me fifty cents or a dollar."

"I rode the trains down through the Cascade Mountains. It was beautiful country, but cold as hell. I would lie up on a freight car, and when we'd go through a long tunnel, I wondered if I was going to live to see the other end. Still, I wouldn't spend this money. I was so proud to be taking money home." (Hays-Houston taped conversation, Lee Hays Collection, Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies Archive, Smithsonian Institution.)

Like many families, they survived on what each member of the family brought home and through the generosity of neighbors. Cisco also saw his mother walk for miles in order to earn a little money doing housework; later, he sang protest songs based on experience, not just sympathy for down-and-out and oppressed fellow citizens.

It was during those early years of wandering when he stopped long enough in a small California town to borrow its name. Cisco, California, is on present-day Interstate 80 (originally highway US 40) between Reno, Nevada, and Sacramento. The town has also been known as Cisco Grove and currently maintains a summer population of approximately 160. At an elevation of 5,923 feet, it is about twenty miles west of the historic Donner's Pass where winters can be deadly. It is so small that it is not in the index of most California maps and guides, but while visiting it, Gil Houston became "Cisco" Houston.

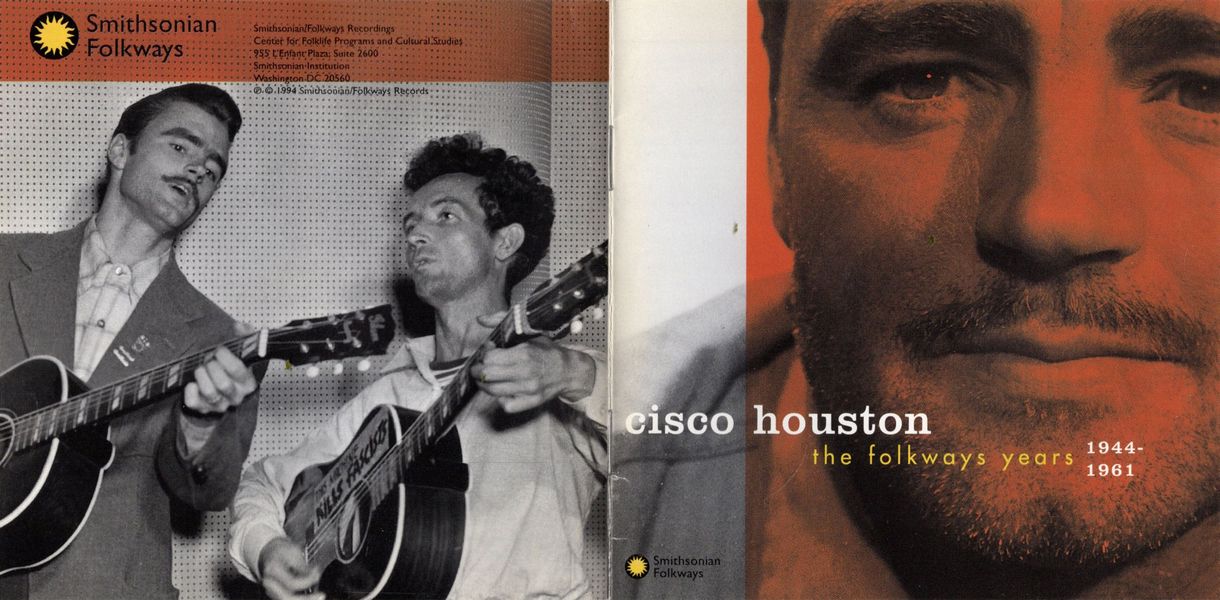

Stopping long enough in Hollywood to work in a little theater group, Cisco met Will Geer. They remained close friends the rest of his life, and that friendship led him to Woody Guthrie. It was 1938, and Woody Guthrie had his radio show on KFVD in Hollywood. Cisco and Will heard Woody's show and decided that they should meet him. About Woody's radio personality, Cisco later said, "I really liked him; he was a relief from the hillbilly singers. He sang his own songs in a straightforward, down-to-earth kind of communication." He and Will Geer went to the radio station and "hauled him home with us." (Houston-Claypool interview, Cisco Houston Papers.)

Cisco knew many of the old songs Woody knew; they started singing together and developed a close, fast friendship. Cisco sang a solid tenor harmony to Woody's melody line and soon was singing with him on his radio program. He recalled, "Woody's mailbox at the station was always full … I would help him open the letters and count the quarters, which he always shared with anyone who needed a few — and I did. Those were hard days!" (Houston-Claypool interview.)

They toured migrant labor camps with Geer paying the expenses and with Burl Ives occasionally joining them. In 1939 Geer wanted Woody to go to New York City with him, and since Cisco had made his first trip back to the East Coast in 1936 and knew of the activities and opportunities, he encouraged Woody to go with Geer. Later that year Cisco returned to New York and found a job as a street barker for a burlesque house on 42nd Street, and he and Woody resumed singing together. He often summarized Woody's influence with just a few words: "I learned a lot from Woody."

In 1940, prior to the United States entering World War II, Cisco joined the Merchant Marines and shipped out often; each time he returned, he made appearances with Woody and, occasionally, the Almanac Singers. During the war, Woody obtained his papers and joined Cisco at sea; they sailed together three times and were on two torpedoed ships.

Through these years, Cisco wandered in and out of New York City, sometimes staying with Martha and Huddie Ledbetter. During his travels he worked as a cowboy, a lumberjack, a potato picker, and at a wide variety of common labor jobs, and he learned songs as he worked and traveled. He played small roles in a few movies and appeared on numerous radio shows. He claimed that he made a minimum of thirty treks across the country; it is probable that Woody was the only folksinger who wandered around the nation as much as Cisco.

Woody started his recording sessions with Moses Asch in 1944 and soon had Cisco working in the sessions with him. Asch recalled, "He helped Woody; they could play duets. Cisco was so good at the guitar, and so good at adapting himself with others. Woody could do whatever he wanted to do without having to worry what the next guy was doing, because Cisco covered up. All of this was spontaneous, unrehearsed" (Asch-Logsdon interview). It was Asch who convinced Cisco to record his own songs as well as songs from his repertory.

Cisco was a humble person. He developed his flat-pick guitar style with Woody's assistance; however, when plucking (pulling the strings with his fingers), he played a style similar to that of Burl Ives. He often stated that he was not a good guitarist.

He was far better than he believed, for instead of using the instrument to cover vocal weakness and/or to impress an audience, he used it tastefully to support his vocal style.

When he sang with Woody, he adapted his voice quality to blend with Woody's, and usually sang a thin, high-pitched tenor harmony. But when singing solo, his voice was an open and relaxed natural baritone, and he made no attempt to change his voice to conform to how others thought a folksinger should sound. Folksinger Katie Lee, who was a close friend of Cisco's in California during the early 1950s, believes that he "had the most beautiful voice" of all the folksingers. It was his excellent singing ability, no doubt developed during his acting lessons, that attracted criticism from the crowd that believed folksingers should sound untrained. But with his background Cisco was truly a "folk" singer.

Moses Asch referred to those who changed their voices and accents in front of an audience to fit a preconceived "folk" sound as singers who practiced "folk" professionalism. Asch said, "Cisco never gave a damn, always was against this [professionalism] and lost out because of that" (Asch-Logsdon interview).

Cisco was critical of similar attitudes when in an interview he said:

"There's always a form of theater that things take; even back in the Ozarks, as far as you want to go. People gravitate to the best singer … We have people today who go just the other way, and I don't agree with them. Some of our folksong exponents seem to think you have to go way back in the hills and drag out the worst singer in the world before it's authentic. Now this is nonsense … Just because he's old and got three arthritic fingers and two strings left on the banjo doesn't prove anything." (Houston-Claypool interview.)

Cisco was not critical of high quality authentic untrained folksingers; he was critical of those who specialized in promoting poor quality as "pure" folk authenticity. He did have an element of bitterness about the critics who believed his voice was too good to be accepted as a folksinger. He just happened to have a nice voice and did not mind using it in an honest way singing the songs he loved and in which he believed.

With acting as his first love, in 1948 he landed a role in the Broadway play The Cradle Will Rock. The following year he was back in California with minor roles in movies and stage plays. Then in 1950 he traveled for a while with Woody, and in September 1951, Decca Records, the company that had enjoyed much success with the Weavers before they were blacklisted, recorded two songs sung by Cisco, but did not release them. On February 5, 1952, they recorded and later released records of him singing his songs, "Rambling Gambling Man" and "Green Lilac Hills," and in June 1952 they recorded two more songs that were not released. George Barnes, the popular swing/jazz guitarist, and his small band were the studio musicians for all sessions. The session cards say "Gil Houston," and his photos on the published sheet music picture him with no moustache. This is strange, for in all other photos, he has a moustache. It may have been an attempt to avoid the blacklist. That year, he also worked in television in Tucson, Arizona, for a short time.

Two years later his greatest opportunity for entertainment and financial success came in Denver, Colorado; he was given his own radio show. On Monday, November 15, 1954, the Intermountain Network with major sponsorship introduced the Gil Houston Show; they sent a memo to their affiliate stations promoting " … GIL HOUSTON, a fresh and vibrant personality Nationally [sic] recognized and in our estimation the finest folk singer that has ever been presented, not barring Mr. Burl Ives." The show aired at 6:15 p. m. on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.

One sponsor of the show ran newspaper ads with Cisco's photo stating, " … we at Englewood Savings and Loan are indeed proud to introduce Gil Houston to Denver and Colorado. We are sure this young artist who has sung his way to the top in the folk music field will sing his way into the hearts of radio listeners all over Colorado and the Rocky Mountain Region. Welcome to Denver, Gil, we know you'll be happy here." He had a hit show, and on January 13, 1955, the show was fed directly to the five hundred and fifty stations in the Mutual Broadcasting System.

His song "Crazy Heart," co-authored with Lewis Allen and recorded by Jackie Paris on Coral Records, was rapidly climbing the charts. It appeared that Cisco was destined to receive well-deserved recognition, but by mid-summer his show was off the air.

There is no documentation to explain what happened, but Moses Asch stated that Cisco was removed from radio because of his radical views. The pressures of McCarthyism and the blacklist were rampant throughout the entertainment industry, and while Cisco was never blacklisted, it is probable that when, in order to promote his Folkways albums he revealed that Gil and Cisco were the same, the red-baiters scared the sponsors. He was a friend of and had recorded with most of the folksingers under attack.

After his Denver show ended, Cisco returned to California, where he gave concerts wherever he was invited — colleges, churches, nightclubs, anywhere they wanted to hear him. Then another opportunity to revitalize his career arose. In 1959 he was invited to tour India sponsored by the Indo-American Society and the U. S. Information Service. For twelve weeks in early 1960, Cisco along with Marilyn Childs, Sonny Terry, and Brownie McGhee enjoyed appreciative crowds at all of their shows in India, and on his way home, Cisco gave concerts in England and Scotland.

Upon returning to the United States, he was chosen to be the leading narrator/performer of the Revlon Hour Spring Festival of Music, "Folk Sound U.S.A.," aired over CBS Television on June 16, 1960. It was the first full length folk music show on television, and featured along with Cisco, Joan Baez, John Jacob Niles, John Lee Hooker, Earl Scruggs and Lester Flatt, and others. The show received mix reviews; however, in Variety, June 22, 1960, Cisco was praised: "Cisco Houston made a great narrator, and his songs were straightforward and well handled."

Later in that summer of 1960, he was featured at the Newport Folk Festival, and recorded enough songs for Vanguard Records eventually to issue three longplay (LP) records. Unfortunately, some of the songs were over-produced to attract the popular music market. He also booked a number of nightclubs and folk concerts for the summer and fall; once again, it appeared that he might enjoy well-deserved fame and success. But during the summer, he learned that he had cancer and had little time to live. He played his concerts as long as he could, and then quietly returned to California and his family.

In his visits with Lee Hays only three months before he died, he jokingly reflected about death: "The trouble with my whole life has been that my timing is always bad" (Hays, "Cisco's Legacy," in Sing Out! October-November 1961). In an interview two weeks before his death, Cisco fondly recalled conversations with young people who wanted to travel as he and Woody did:

"Everybody hates to have two things said about 'em, and one is that they never known [sic] trouble or they don't have a sense of humor … so much of folkmusic is about trouble and being able to laugh at troubles and everything else. Of course, a lot of these college kids haven't experienced anything like that in their lives, but they like to identify with that kind of thing. I have young kids come to me all the time and ask me about my days on the road. It's very romantic to them. I try to dissuade them from just going out like that … we did that in those days 'cause we had to, not because we wanted to." (Houston-Claypool interview)

Gilbert V. "Cisco" Houston died on April 28, 1961, at the age of forty-two. Shortly after, Lee Hays wrote, "Cisco touched people … He knew his own imperfections better than anyone. But he walked with grace through an imperfect world, and the world will be better because of the lives he touched" (Hays, "Cisco's Legacy").

Moses Asch and Irwin Silber edited a collection of songs in tribute to Cisco, 900 Miles: The Ballads, Blues and Folksongs of Cisco Houston (New York: Oak Publications, 1965), in which Asch wrote, in a letter to the late singer: " … I think more records were cut with you on them, working with Woody, Leadbelly, and the others who hung around the Asch office to record and talk, than any other musician outside of Sonny Terry … Your belief in man and that Woody was communicating man in his song and expression made both of you a together ness. It was a team that I and many others will remember."

His friend and manager Harold Leventhal wrote in the press release announcing the death of Cisco:

Those of us, and there are many, who have known and worked with Cisco over the past years, have known so few persons about whom one could say he was truly a great guy. As a folksinger, he possessed a remarkable voice He was indeed a very creative person A song writer, singer, union organizer were but a few of the areas in which he excelled.

He was above all a genuine person, loved by all, admired by many …

To the very end he possessed indomitable courage in the face of this disease — courage augmented by his deep concern for the great problems that faced those of us who survived him — the hope for a world of tranquility and peace! To Cisco we sing, "So Long, It's Been Good to Know You."

Notes on the songs

The dates of Cisco's recording sessions, other than those made with Woody Guthrie and others between 1944 and early 1947, were not documented, and acetate masters of Cisco's solo recordings are not in the Asch/Folkways Collection. It is probable that Asch started using tape recorders in 1947 or early 1948, that session documentation was not made after he started using tape recordings, and that most of Cisco's single artist recordings were taped recordings.

Moses Asch planned to issue a Cisco Houston album as early as June 1, 1947 (listed in the "Disc Record List"), and may have sold a few copies. If so, they are elusive. The album, according to Disc Company of America Bulletin 41, was to be Cisco Houston — Cowboy Songs, Album 608, with liner notes written by Woody Guthrie. The songs were:

Asch and his company, Disc, were in financial trouble by mid-1946, and in early 1948 Asch attempted to negotiate a twenty-five percent on the dollar payout to his creditors. The company went out of business, and Asch reorganized as Folkways Records. And there is no evidence that the Cisco Houston album was actually recorded, pressed, and released; only one song, "Tying a Knot in the Devil's Tail, " appeared in his later Folkways cowboy song records, and Stinson Records did not issue this Cisco Houston album.

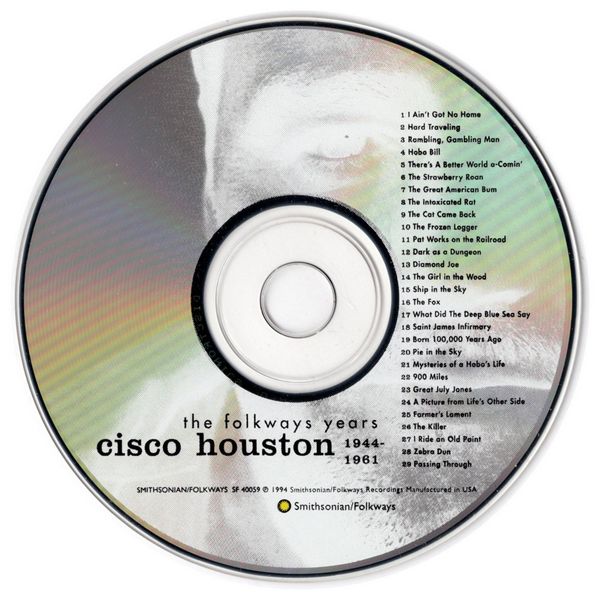

In 1948 Asch did issue Nursery Rhymes "sung and played by Cisco Houston" on his Cub Records label; there were ten short musical rhymes for "age group 2-4" on a ten-inch 78 rpm disc, Cub 11. A few of Cisco's solo songs were included in Folkways anthologies issued prior to 1952. His first long play record was Cowboy Songs FA 2022 (10" lp, 1952), notes by J. D. Robb, which was followed by 900 Miles and Other Railroad Songs FA 2013 (10" lp, 1953), notes by Charles Edward Smith; Hard Travelin' FA 2042 (10" lp, 1954), notes by Kenneth S. Goldstein; Cisco Sings FA 2346 (10" lp, 1958), notes by Cisco Houston; Cisco Houston Sings Songs of the Open Road FA 2480 (12" lp, 1960, 1962), short autobiographical note by Cisco Houston, no song notes; Passing Through Verve/Folkways FV/FVS 9003 (12" lp, 1963), short statement by Cisco Houston, no song notes; and Cisco Houston Sings American Folksongs FT 101 2/FTS 31012 (12" lp, 1968), a reissue of Cisco Sings, notes by Cisco Houston with a tribute written years earlier by Woody Guthrie.

Not all of the cuts on Songs of the Open Road and Passing Through were recorded by Asch in his studio. No documentation has been located to identify who engineered them and where the sessions were made, but unissued takes with limited conversations indicate they were not made by Asch. We can assume that the sessions were in California, recorded by friends of Cisco. This was not unusual, for many Folkways records issued by Asch were from taped recordings sent to him.

In 1964, Asch planned to issue a series of long play recordings under the Disc Recordings label. Press releases and catalog entries have not been found for any of the titles; therefore, it appears that only a few copies were pressed and that not all of the planned titles were even pressed and issued. Cisco Houston — A Legacy Disc D-103, containing twelve songs, was one of the collections, and the only copy located is in the Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies Archive, Smithsonian Institution.

Collectors of Cisco Houston material are aware that Stinson Records issued recordings that included many of his recordings. During World War II, Asch and Herbert Harris, the owner of Stinson, were partners in Asch-Stinson Records. Asch had the studio and engineering ability, and Harris had access to shellac necessary to produce records. In 1947, during his Disc Company financial problems, the partnership was dissolved. Harris received some master acetates and unsold albums, and produced 78 rpm albums and longplay records from his stock. Thus, there are Stinson releases identical to those issued by Asch before mid-1947; there also are record companies that have used the Stinson recordings for their unlicensed releases.

Unless otherwise indicated the following songs are Cisco Houston, vocal and guitar.

I Ain't Got No Home — (From Songs of the Open Road FA 2480, 1960, 1962; new words and adapted music by Woody Guthrie)

Woody Guthrie took the traditional white spiritual, "This World Is Not My Home," also known as "I Can't Feel at Home in This World Anymore," and rewrote the words to express the plight of migrants during the Dust Bowl and Great Depression. He heard the Carter Family version of the spiritual either on record or over one of their many border radio broadcasts, such as XERA, Del Rio, Texas, and adapted it. Woody wrote his version during his days at KFVD, Hollywood, 1937-38. This version was first recorded by Woody Guthrie, March 22, 1940, for the Library of Congress.

Hard Traveling — (From Hard Travelin' FA 2042, 1954; words and music by Woody Guthrie) ;

The first printing of this song appeared in a typed and mimeographed collection, Ten of Woody Guthrie's Songs, New York City, dated April 3, 1945, which the author sold for twenty-five cents or less. He wrote, "This is a song about the hard traveling of the working people, not the moonstruck mystic traveling of the professional vacationist." Woody wrote it while working on his Columbia River project in 1941 and first recorded it, with Cisco accompanying him, for Asch in mid-1945.

Rambling, Gambling Man — (This version is previously unissued, from the Archives of the Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies, Smithsonian Institution; a different version was issued on Cisco Houston Sings American Folk Songs FT 1012 Mono, FTS 31012 Stereo, 1968, originally issued as Cisco Houston Sings FA 2346, 1958; words and music by Gil Houston; sheet music published by Ludlow Music, New York, 1952.)

Cisco adapted the traditional song, "The Roving Gambler," into a contemporary Las Vegas, Nevada, gambler's song. He recorded it for Decca Records, February 5, 1952; released as Decca 28065 on April 14, 1952, it did not sell well. His method of pulling a guitar string, creating a sense of hesitancy for emphasis, is the basic difference between this version and the previously issued Folkways version.

Hobo Bill — (This version is previously unissued, from the Archives of the Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies, Smithsonian Institution; a different version was issued on 900 Miles and Other Railroad Songs FA 2013, 1953; words and music by Waldo L. O'Neal, 1929.)

The influence of Jimmie Rodgers, "The Singing Brakeman," is heard on this version. Cisco yodels and sings "Hobo Billy," which is almost identical to how Rodgers recorded it; on the previously issued version, he does not yodel and sings "Hobo Bill." First recorded by Jimmie Rodgers, November 13, 1929, New Orleans (Victor 22421).

There's A Better World A-Comin' — Woody Guthrie, lead vocal and guitar; Cisco Houston, harmony vocal. This is a previously unissued track from the Archives of the Center for Folk-life Programs and Cultural Studies. A different version was issued on Bound For Glory (FP 78/1 in 1956; FA 2481 in 1961), as well as on Original Recordings Made by Woody Guthrie: 1940-1946 Warner Brothers Records BS 2999, 1977. Alternate titles for this song are "Better World" and "Better World A-Coming."

There is no information in the Asch/Folkways Archives to indicate when either version of this song was recorded; however, manuscripts in the Archives of the Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies indicate that it was a World War II song expressing hope that a "better world" would come from the killing, bombing, pain, misery and crying. This version was probably recorded before mid-1945, for even though it has a strong endorsement of unions, the theme supports the belief that the war would build a worldwide union of working people. The two manuscripts in the Asch/Folkways archives have similar lines, yet vary significantly; neither is identical to the recorded versions. The first printed variant is anti-fascist and anti-racist (Woody Guthrie Folk Songs, New York: Ludlow Music, 1 963 p. 193), but it, too, varies from the recordings and manuscript. This track is an example of how Woody and Cisco improvised as a team.

Cisco can be heard singing a strong supporting harmony behind Woody. Since they were close friends, and Cisco's belief in a better world through united workers was equal to, or stronger than, Woody's, it is probably that Cisco contributed ideas and lines to this and other songs created by Woody.

The Strawberry Roan — Cisco Houston, vocal and guitar; Woody Guthrie, mandolin.

(Previously unissued, from the Archives of the Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies, Smithsonian Institution; recorded April 19, 1944, matrix MA54; words by Curley Fletcher circa 1914, music traditional.)

This is possibly the first solo recording Cisco made for Asch, recorded in a Woody Guthrie/ Cisco Houston session, during which they recorded other cowboy songs with Woody as the lead singer. Asch intended to use it in a cowboy album that, for unknown reasons, was never released.

First recorded by Paul Hamblin, March 21, 1930, Culver City, California (Victor V40260). For additional information about the song, see: Guy Logsdon, "The Whorehouse Bells Were Ringing" and Other Songs Cowboys Sing (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989), pp. 86-96, and John I.

White, Git Along, Little Dogies (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1975), pp. 137-147. This song is still widely sung and recited by working cowboys.

The Great American Bum — (From 900 Miles and Other Railroad Songs FA 2013, 1953; authorship claimed by "Haywire Mac" McClintock.)

"Haywire Mac" hoboed and sang across the country; he was one of the most colorful figures in hobo and railroad music, and he claimed to have written such classic songs as "The Big Rock Candy Mountain." This is another one that he claimed as his own. About this song, George Milburn wrote, "Most hobos are migratory workers who lead the wandering life from choice … The following humorous song, from Paul Dooley's repertory, catches the fascination of hobo life, as well as listing some of the hobo's occupations." For additional information, see: George Milburn, The Hobo's Hornbook (New York: Ives Washburn, 1930), pp. 70-73, and Henry Young, "Haywire Mac" and the "Big Rock Candy Mountain" (Temple, Texas: Still-house Hollow Publishers, 1981).

The Intoxicated Rat — (From Hard Travelin' FA 2042, 1954; words (unknown], music adaptation of "Our Goodman.")

Little is known about the adaptation of this song, other than the melody is a version of "Our Goodman" (Child ballad 274), also known as "Four Nights Drunk." It was first recorded by the Dixon Brothers, February 12, 1936, Charlotte, North Carolina (Bluebird B6327), and became one of their most popular songs. If not written by them, at least, they created its popularity.

The Cat Came Back — (From Passing Through Verve/Folkways FV/FVS9002, n.d. [circa 1966]; original words and music by Harry S. Miller, 1893.)

Humorous songs about animals have been popular with adults as well as children, and a few enter oral tradition with locations, events, and dates changing with each generation. Originally a parlor song written by popular song writer Harry S. Miller, it was adapted to a contemporary setting by Cisco. For additional information, see: Lester S. Levy, Flashes of Merriment (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971), pp. 227, 238-40. First recorded by Fiddlin' John Carson, April 1924, Atlanta, Georgia (Okeh 401 19).

The Frozen Logger — (From Hard Travelin' FA 2042, 1954; words James Stevens, music adaptation of "When I Was Young and Foolish;".)

While Stevens is credited with this humorous lumberjack song, he wrote in 1949 that he coauthored it with H. L. Davis in 1929; however, in the March 1, 1959, book section of the New York Times, H. L. Davis is quoted saying that he wrote it in 1928 in Seattle, Washington. Stevens said that it was written for a radio series about Paul Bunyan, while Davis said that it was written for a program trying "to lure sponsors from the lumbering industry." Davis was contracted to supply loggers' folksongs, but there were not enough, "so I started writing them, and adapting them to any old tunes I could dig up." It is probable that both men had a hand in writing it. It was popular in the Northwest due to numerous radio broadcasts, and in 1951 the Weavers spread it nationwide through their recording and personal appearances.

Pat Works on the Railroad — (From Sings American Folk Songs FT 1012 Mono, FTS 31012 Stereo, 1968, originally issued as Cisco Houston Sings FA 2346, 1958; words and music traditional.)

Immigration from Ireland to the United States for well over a century accounted for the largest number of immigrants from one nation to this country. From their ranks came a high percentage of the labor force that built the railroads, and they made an impact on the folk music of this nation. This song is not a traditional Irish song, but probably came from music hall writers who often used ethnic humor as a theme in their songs. It is also known as "Paddy Works on the Railway"; for a thorough discussion of "Paddy," see: Norm Cohen, Long Steel Rail (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981), pp. 547-552.

Dark as a Dungeon — (Previously unissued, from the Archives of the Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies, Smithsonian Institution; words and music by Merle Travis) ;

Merle Travis perfected the guitar finger-picking style that has influenced generations of guitarists, including Chet Atkins. He also wrote songs that will last as long as the Travis guitar style. His songs made a few singers famous, such as Tex Williams singing "Smoke, Smoke, Smoke That Cigarette," and Tennessee Ernie Ford's rendition of Travis's "Sixteen Tons" stayed on the country music charts for twenty-one weeks. In the 1 940s, Travis singing his own songs was a major figure over the radio airwaves, and his recording of "Divorce Me C. O. D." in 1946 saved Capitol Records from bankruptcy. Born in Rosewood, Kentucky, into a coal mining family, Travis took his guitar and talent to Hollywood and to Capitol Records. In 1947 he recorded a collection of Kentucky folksongs, Folk Songs of the Hills, including traditional songs and his own compositions. "Dark as a Dungeon," which was his composition, was included in the album, and it along with the other coal mining songs became standards among traditional and professional singers. A few years ago, a Welsh song collected in Monmouthshire, Wales, and similar to this one surfaced; speculation was made that Travis adapted his song from this folksong. This is highly improbable, for no similar song was known to exist in this country prior to his 1947 release. Instead, it is more likely that the Welsh song was adapted from Travis's song.

Diamond Joe — (From Cowboy Ballads FA 2022, 1952; words [unknown], music adaptation of "The State of Arkansas.")

"Diamond Joe" as sung by Cisco is more than an adaptation of a melody; the lyrics are also an adaptation of "The State of Arkansas." Arkansas has long been the target of humor, and even though John A. Lomax included the humorous song "The State of Arkansas" in the different editions of Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads, the version most widely known was Lee Hays's. Lomax also included a "Diamond Joe," but it is very different from this song. And the Southern prison song heard on Afro-American Blues and Game Songs (AFS L4) issued by the Library of Congress is also different from this one. Since Cisco's version is unique with him, it is speculated that either he or Lee Hays adapted it into a cowboy protest song. Lomax states that the Texan Diamond Joe "wore big diamond buttons on his vest."

The Girl in the Wood — (From Hard Travelin' FA 2042, 1954; words and music by Terry Gilkyson and Neal Stuart)

This is one of the most beautiful songs in Cisco's repertory. The theme is that of the "enchantress," in fact, a red haired, green-eyed enchantress; however, in this song the young man does not lose his soul or life. Instead, when he looks into her eyes, he loses all desire for other women. The popular singer Frankie Laine recorded this song in 1951.

Ship in the Sky — (Previously unissued on Folkways Records, from the Archives of the Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies, Smithsonian Institution; words and music by Woody Guthrie)

In this song, Woody imparts to children the importance of respect and cooperation, and expresses the importance of each worker, no matter how menial or high-powered the position. There are alternate titles to the song, but this title is the one Woody used. It first appeared in his typed and mimeographed collection, Ten of Woody Guthrie's Songs, New York City, dated April 3, 1945, but the exact date of composition is not known.

The Fox — (Previously unissued, from the Archives of the Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies, Smithsonian Institution; traditional.)

Dating back at least to the 1700s, "The Fox" has maintained popularity with all ages of singers and audiences. It was sung at harvest suppers in England, and traveled across this country in a variety of settings. Perhaps its acceptance in modern twentieth-century urban settings is because of Burl Ives, for it was one of his most popular recordings. Contemporary performers of this song are often unaware that they are singing a version very similar to Ives's adaptation.

What Did the Deep (Blue) Sea Say? — Woody Guthrie, lead vocal and guitar; Cisco Houston, harmony vocal and guitar. Recorded April 1944. Stormking Music 1962. This track is a previously unissued version of the song from the Archives of the Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies. It is, however, very similar to the version on Woody Guthrie Sings Folk Songs (SF 40007).

Woody Guthrie's first studio session for Moses Asch was in March 1944. On 19 April, 1944, he and Cisco returned to the studio for a lengthy session, recording over thirty songs. This track is listed by the shortened title "Deep Sea" (Matrix MA48). Between 25 April and 8 May 1944 (exact date unlisted) they recorded approximately 25 more songs, including a second version of "Deep Sea" (Matrix MA 120). Due to Asch's inadequate identification and filing techniques, accurate discographic description is impossible. We also do not know when or where Woody and Cisco learned the song. However, the title used is Woody's title, and the melody and words were adapted by Woody.

The song is an Americanization of the British broadside, "The Sailor Boy" (see Malcolm Laws, Jr., American Balladry from British Broadsides, Philadelphia: American Folklore Society 1957, pp. 146-147). Variants have been recorded since the 1920s by various artists, including the Carter Family, the Monroe Brothers, and the New Lost City Ramblers. The titles and variants are as diverse as the artists: "Captain, Tell Me True," "Where Is My Sailor Boy?" "Sailor On the Deep Blue Sea," and "I Have No One To Love Me." The chorus and melody used by Woody and Cisco vary little from the chorus and melody used by the Monroe brothers, but only a few lines in the verses are the same. Woody, as he often did, rewrote this song; the verses in this variant differ from those in his own notebook of songs "Songs of Woody Guthrie" (typescript), at the Library of Congress Archive of Folk Culture.

In this recording, Cisco can be heard playing runs on the lower strings of his guitar as well as singing excellent harmony to Woody's melody. For additional information, see Sing Out! 26 (January-February 1978) 5:1 and 17 as well as December/January 1968 6:26.

Saint James Infirmary — (From Sings American Folk Songs FT 1012 Mono, FTS 31012 Stereo 1968, originally issued as Cisco Houston Sings FA 2346, 1958; traditional)

Usually considered to be a distant relative of "The Unfortunate Rake," this song, according to Kenneth Goldstein, does not date from before 1910. First recorded in the 1920s as "The Gambler's Blues," it has similarities to "The Unfortunate Rake" only in the funeral request verses. For an excellent study of the "Rake" cycle, see: The Unfortunate Rake: A Study in the Evolution of a Ballad, notes by Kenneth S. Goldstein, Folkways Records FA 3805, 1960.

Born 100,000 Years Ago — (Previously unissued, from the Archives of the Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies, Smithsonian Institution; original words to "I Am a Highly Educated Man" by H. C. Verner, music by Harry C. Clyde, 1894; adapted and arranged by John A. and Alan Lomax)

The nineteenth-century American frontier character encouraged the tall tale and the braggart, and it inspired an irreverence toward the Bible and, to some extent, toward the classroom. This late-nineteenth-century popular song combined those prevailing attitudes into comic Biblical and historical relief. The writers composed a song that is easily adaptable, which is what Woody Guthrie did when he wrote "The Biggest Thing That Man Has Ever Done." However, Cisco's version is closer to the one published in John A. and Alan Lomax, Folk Song U.S.A. (New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1947), pp. 9-10, 30-31. The first documented title change from the original, "I Am a Highly Educated Man," was when Fiddlin' John Carson recorded it as "When Abraham and Isaac Rushed the Can," in March 1924, Atlanta, Georgia, (Okeh 40181). The following year Kelly Harrol recorded it, using the title "I Was Born About 10,000 Years Ago," in August 1925, Asheville, North Carolina,(Okeh 40486).

Pie in the Sky — (From Songs of the Open Road FA 2480, 1960, 1962; words by Joe Hill, music "In the Sweet Bye and Bye.")

Joe Hill, born Joel Hagglund, was a Swedish immigrant who became a legendary and martyred member of the Industrial Workers of the World and a songwriter who provided the I.W.W. with song ammunition to fight their battles. Originally titled "The Preacher and the Slave," it first appeared in the 1911 printing of the I.W.W.'s Little Red Songbook; for more detailed information about Joe Hill and his songs, see: Don't Mourn — Organize! Songs of Labor Songwriter Joe Hill, notes by Lori Elaine Taylor, Smithsonian/Folkways Recordings SF 40026, 1990 (Cisco can also be heard singing Joe Hill's "The Tramp" on this recording). The song became popular among hoboes, who, according to George Milburn, had a "resentful attitude toward organized religion"; see: Milburn's The Hobo's Hornbook (New York: Ives Washburn, 1930), pp. 83-85. The earliest recording was Charlie Carver, December 12, 1929, New York City (Brunswick 392).

Mysteries of a Hobo's Life — (From Songs of the Open Road FA 2480, 1960, 1962; words by T-Bone Slim, melody "The Girl I Left Behind Me.")

Cisco may have learned this song while traveling across the country, but it is probable that he took it from George Milburn's The Hobo's Hornbook (New York: Ives Washburn, 1930), pp. 108-109. Milburn credits T-Bone Slim, "a wobbly writer who has been credited with having coined many hobo slang terms heard in the jungles today," as its author.

900 Miles — (From 900 Miles and Other Railroad Songs FA 2013, 1953, traditional.)

The earliest recording of a title similar to this one was Fiddlin' John Carson's, "I'm Nine Hundred Miles from Home," August 27, 1924, Atlanta, Georgia (Okeh 40196). However, Norm Cohen believes that it is a variant of the railroad song, "Reuben, Oh, Reuben." Woody Guthrie recorded two versions (one in a major key, the other in a minor key) of "900 Miles" in April 1944, and Cisco accompanied him on both. Cohen states that "there is no doubt that he (Woody) was responsible for the wide dissemination and popularity of the song from the 1940s on," but the song's popularity during the urban folk revival came as much, or more, from this recording in the minor key by Cisco. For additional information, see: Norm Cohen, Long Steel Rail (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981), pp. 503-517.

Great July Jones — (From Sings American Folk Songs FT 1012 Mono, FTS 31012 Stereo, 1968, originally issued as Cisco Houston Sings FA 2346, 1958; words and music by Lewis Allen and Gil Houston)

Cisco previously recorded this for Decca Records on June 30, 1952 (matrix 83019), accompanied by George Barnes and the Barnes Stormers, but it was never released. He referred to it as "a tall tale, boasting song." According to those who knew him, some lines could be autobiographical: "He's got a way you can't resist/Kisses the girls and they stay kissed."

A Picture from Life's Other Side — Cisco Houston, harmony and guitar; Woody Guthrie, lead vocal and mandolin; Bess Hawes, harmony.

(From Woody Guthrie Sings Folksongs with Cisco Houston and Sonny Terry Folkways FA2484; recorded 25 April 1944 matrix MA82; words and music by Charles E. Baer, 1896.)

Woody used this song for his radio show over KFVD, Hollywood, and included it in the song book, Woody and Lefty Lou's Favorite Collection [of] Old Time Hill Country Songs (Gardena, California: Spanish American Institute Press, 1937), p. 9. It was a late-nineteenth-century sentimental song that appealed to folk and country singers. Vernon Dalhart popularized it, but it was first recorded by Smith's Sacred Singers, April 22, 1926, Atlanta, Georgia (Columbia 15090-D).

Farmer's Lament — (Previously unissued; words and music by Les Rice)

Les Rice was a man of varied talents and interests who expressed his social concerns through song writing; his best known song is "Banks of Marble." Though a native of Brooklyn, New York, he was dedicated to the problems of small farmers and became a fruit farmer in the mid-Hudson Valley. This song was probably written in the early 1950s, and expresses the problems small farmers confront in their effort to survive. Cisco's version is apparently the only commercial recording of the song.

The lyrics and melody line are found in a small collection of Rice's songs (brought to my attention by Joe Hickerson) edited by his widow, Nancy Rice, and friends, Banks of Marble: The Songs of les Rice, Highland, NY: Friends of Les Rice, 1989. It was on "an old tape," and transcribed by Sis Cunningham. The melody used by Cisco along with the lyrics are basically the same; the variations are those that come with modifying a song from memory to fit the flow of Cisco's singing and speech style. However, the fourth verse sung by Cisco is not in the Rice version, and Cisco sings a one-line refrain after each verse, "It's hard, hard on my hard working farm." Since the refrain is not in the Rice version, it is possible that through his creativity Cisco may have added it.

The Killer — (From Sings American Folk Songs FT 1012 Mono, FTS 31012 Stereo, 1968; originally issued as Cisco Houston Sings FA 2346, 1958; words, traditional, music, Cisco Houston.)

Katie Lee taught this song to Cisco when they were dating in California during the early 1950s. When he told her he was going to record it, she reminded him that she had written the melody and that it was copyrighted. It angered Cisco, so he modified the melody enough to call it his own. Katie Lee uses the title, "'Dobie Bill," and the lyrics came from John A. and Alan Lomax, Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1938, reprinted 1986), pp. 172-175. It probably came from the pen of a romance writer, for it does not contain terminology and action that working cowboys would use. For additional information, see: Katie Lee, Ten Thousand Goddam Cattle (Flagstaff, Arizona: Northland Press, 1976), pp. 10-11, 195-96.

I Ride an Old Paint — (From Cowboy Ballads FA 2022, 1952; words and music traditional.)

Woody Guthrie recorded this with Pete Seeger, July 7, 1941, for General Recordings (released on Sod Buster Ballads General Album G-21); Woody is credited with writing the verse that starts with, "I've worked in your town, I've worked on your farm." He wanted it to sound more like a worker's song than a lyrical cowboy song. It has been a popular cowboy song since the early 1930s; for additional information, see: Jim Bob Tinsley, He Was Singin' This Song (Orlando: University Presses of Florida, 1981), pp. 126-129. It was first recorded as "Riding Old Paint, Leading Old Bald" by Stuart Hamblin, March 3, 1934, Los Angeles, California (Decca 5145).

Zebra Dun — (From Sings American Folk Songs FT 1012 Mono, FTS 31012 Stereo, 1968, originally issued as Cisco Houston Sings FA 2346, 1958; words and music traditional.)

Also known as "The Educated Fellow," this is one of the oldest and best of traditional cowboy songs, and it shows how cowboys played hard practical jokes — that sometimes backfired. It was first collected and published by N. Howard "Jack" Thorp in Songs of the Cowboys (Estancia, New Mexico: by the author, 1908), pp.27-29, and was first recorded by Jules Verne Allen, April 30,

1928, El Paso, Texas (Victor V40022). For additional information, see: Guy Logsdon, "The Whorehouse Bells Were Ringing" and Other Songs Cowboys Sing (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989), pp. 77-85; John I. White, Git Along, Little Dogies (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1975), pp. 148-152; and Jim Bob Tinsley, He Was Singin' This Song (Orlando: University Presses of Florida, 1981), pp. 134-138.

Passing Through — (From Passing Through Verve Folkways FV/FVS 9002, n.d.; words by Dick Blakeslee, music, traditional)

The influence of Woody Guthrie's "Biggest Thing That Man Has Ever Done" and of "I Was Born 10,000 Years Ago" are heard in this adaptation that pleads for peace. It was published in Irwin Silber, ed., Lift Every Voice (New York:People's Artists, 1953), pp. 16-17.

Acknowledgments

For discographical information, I am indebted to Guthrie T. Meade's unpublished "Discography of Traditional Songs and Tunes On Hillbilly Records," in the Library of Congress, American Folklife Center, Archive of Folk Culture, Washington, D.C. For their encouragement and assistance, I express sincere appreciation to Dr. Anthony Seeger, Jeff Place, Lori Taylor, and Dudley Connell, Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies and Smithsonian/Folkways Recordings, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., and to Joseph C. Hickerson, Gerald Parsons, and the Reference Staff in the Library of Congress, Archive of Folk Culture. I thank Ronnie Pugh, Head of Reference, Country Music Foundation, Nashville, Tennessee, for providing documentation about the Decca recordings. Special appreciation goes to Harold Leventhal for making the Hays-Houston papers available for research and for encouraging me to work with them.

About the compiler

Dr. Guy Logsdon is a Smithsonian Institution Research Associate, and in 1990-91 was a Smithsonian Institution Senior Post-Doctoral Fellow compiling a biblio-discography of the songs of Woody Guthrie. He received a two-year grant, 1993-95, from the National Endowment for the Humanities to complete the Woody Guthrie project. Logsdon has written numerous articles about Woody Guthrie and cowboy songs and poetry and authored the highly acclaimed, award winning book, "The Whorehouse Bells Were Ringing" and Other Songs Cowboys Sing and complied and annotated Cowboy Songs on Folkways Smithsonian/Folkways SF 40043. Former Director of Libraries and Professor of Education and American Folklife, University of Tulsa, Logsdon works as a writer and entertainer.

The Folkways Years Series

Hundreds of artists recorded for Moses Asch, founder of Folkways Records. Asch issued over 2,000 LP titles between 1949 when he founded Folkways and 1987 when it was acquired by the Smithsonian Institution. As part of the Smithsonian's objective of keeping the genius of these artists available to the public, we have begun a series of anthologies that highlight individual artists. The selections are made and annotated by specialists who know the material well, and the tracks selected are intended to be broadly representative of the artists' work on Folkways. Other Folkways Years titles available on CD and cassette are:

About Smithsonian/Folkways

Folkways Records was founded by Moses Asch and Marian Distler in 1947 to document music, spoken word, instruction, and sounds from around the world. In the ensuing decades, New York City-based Folkways became one of the largest independent record labels in the world, reaching a total of nearly 2,200 albums that were always kept in print.

The Smithsonian Institution acquired Folkways form the Asch estate in 1987 to ensure that the sounds and genius of the artists would be preserved for future generations. All Folkways recordings are now available on high-quality audio cassettes, each packed in a special box along with the original LP liner notes.

Smithsonian/Folkways Recordings was formed to continue the Folkways tradition of releasing significant recordings with high-quality documentation. It produces new titles, reissues of historic recordings from Folkways and other record labels, and in collaboration with other companies also produces instructional videotapes, recordings to accompany published books, and a variety of other educational projects.

The Smithsonian/Folkways, Folkways, Cook, and Paredon record labels are administered by the Smithsonian Institution's Center for Folklife Programs and Cultural Studies. They are one of the moans through which the Center supports the work of traditional artists and expresses its commitmen to cultural diversity, education, and increased understanding.