|

|

Sleeve Notes

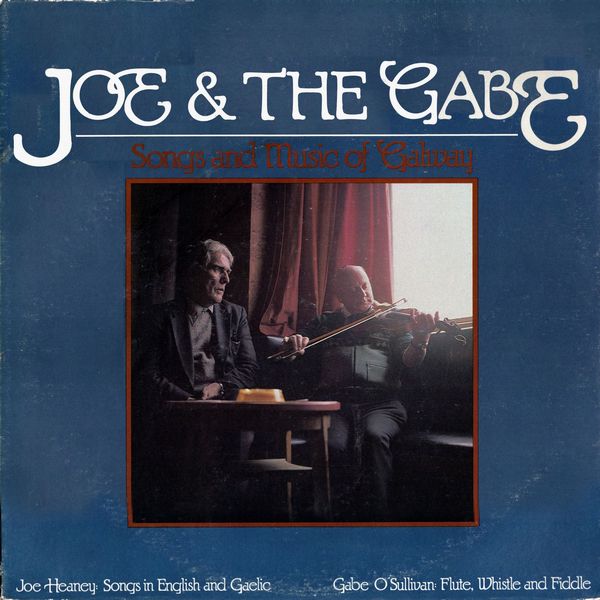

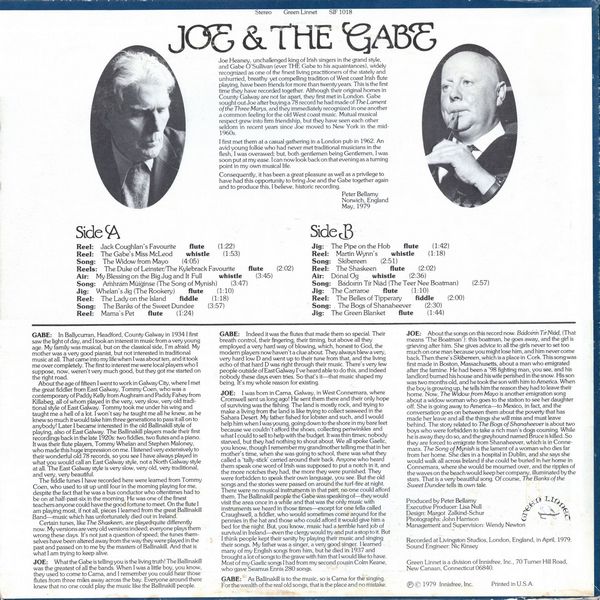

Joe Heaney, unchallenged king of Irish singers in the grand style, and Gabe O'Sullivan (ever THE Gabe to his acquaintances), widely recognized as one of the finest living practitioners of the stately and unhurried, breathy yet compelling tradition of West coast Irish flute playing, have been friends for more than twenty years. This is the first time they have recorded together. Although their original homes in County Galway are not far apart, they first met in London. Gabe sought out Joe after buying a 78 record he had made of The Lament of the Three Marys, and they immediately recognized in one another a common feeling for the old West coast music. Mutual musical respect grew into firm friendship, but they have seen each other seldom in recent years since Joe moved to New York in the mid-1960s.

I first met them at a casual gathering in a London pub in 1962. An avid young folkie who had never met traditional musicians in the flesh, I was overawed; but, both gentlemen being Gentlemen, I was soon put at my ease. I can now look back on that evening as a turning point in my own musical life.

Consequently, it has been a great pleasure as well as a privilege to have had this opportunity to bring Joe and the Gabe together again and to produce this, I believe, historic recording.

Peter Bellamy

Norwich, England

May, 1979

GABE: In Ballycurran, Headford, County Galway in 1934 I first saw the light of day, and I took an interest in music from a very young age. My family was musical, but on the classical side, I'm afraid. My mother was a very good pianist, but not interested in traditional music at all. That came into my life when I was about ten, and it took me over completely. The first to interest me were local players who I suppose, now, weren't very much good, but they got me started on the right road.

About the age of fifteen I went to work in Galway City, where I met the great fiddler from East Galway, Tommy Coen, who was a contemporary of Paddy Kelly from Aughram and Paddy Fahey from Killabeg, all of whom played in the very, very slow, very old traditional style of East Galway. Tommy took me under his wing and taught me a hell of a lot. I won't say he taught me all he knew, as he knew so much it would take him three generations to pass it all on to anybody! Later I became interested in the old Ballinakill style of playing, also of East Galway. The Ballinakill players made their first recordings back in the late 1920s: two fiddles, two flutes and a piano. It was their flute players, Tommy Whelan and Stephen Maloney, who made this huge impression on me. I listened very extensively to their wonderful old 78 records, so you see I have always played in what you would call an East Galway style, not a North Galway style at all. The East Galway style is very slow, very old, very traditional, and very, very beautiful.

The fiddle tunes I have recorded here were learned from Tommy Coen, who used to sit up until four in the morning playing for me, despite the fact that he was a bus conductor who oftentimes had to be on at half-past-six in the morning. He was one of the finest teachers anyone could have the good fortune to meet. On the flute I am playing most, if not all, pieces I learned from the great Ballinakill Band — music which has unfortunately died out in Ireland.

Certain tunes, like The Shaskeen, are played quite differently now. My versions are very old versions indeed; everyone plays them wrong these days. It's not just a question of speed; the tunes themselves have been altered away from the way they were played in the past and passed on to me by the masters of Ballinakill. And that is what I am trying to keep alive.

JOE: What the Gabe is telling you is the living truth! The Ballinakill was the greatest of all the bands. When I was a little boy, you know, they used to come to Cama, and I remember you could hear those flutes from three miles away across the bay. Everyone around there knew that no one could play the music like the Ballinakill people.

GABE: Indeed it was the flutes that made them so special. Their breath control, their fingering, their timing, but above all they employed a very hard way of blowing, which, honest to God, the modem players now haven't a clue about. They always blew a very, very hard low D and went up to their tune from that, and the living echo of that hard D was right through their music. There's very few people outside of East Galway I've heard able to do this, and indeed nobody these days even tries. So that's it — that music shaped my being. It's my whole reason for existing.

JOE: I was bom in Cama, Galway, in West Connemara, where Cromwell sent us long ago! He sent them there and their only hope of surviving was the fishing. The land is mostly rock, and trying to make a living from the land is like trying to collect seaweed in the Sahara Desert. My father fished for lobster and such, and I would help him when I was young, going down to the shore in my bare feet because we couldn't afford the shoes, collecting periwinkles and what I could to sell to help with the budget. It was thin times; nobody starved, but they had nothing to shout about. We all spoke Gaelic, you know, though I remember my grandmother telling me that in her mother's time, when she was going to school, there was what they called a 'tally-stick' carried around their back. Anyone who heard them speak one word of Irish was supposed to put a notch in it, and the more notches they had, the more they were punished. They were forbidden to speak their own language, you see. But the old songs and the stories were passed on around the turf-fire at night. There were no musical instruments in that part; no one could afford them. The Ballinakill people the Gabe was speaking of — they would visit the area once in a while and that was the only music with instruments we heard in those times — except for one fella called Craughwell, a fiddler, who would sometimes come around for the pennies in the hat and those who could afford it would give him a bed for the night. But, you know, music had a terrible hard job of survival in Ireland — even the clergy would try and put a stop to it. But I think people kept their sanity by playing their music and singing their songs. My father was a singer, a very good singer. I learned many of my English songs from him, but he died in 1937 and brought a lot of songs to the grave with him that I would like to have. Most of my Gaelic songs I had from my second cousin Colm Keane, who gave Seamus Ennis 280 songs.

GABE: As Ballinakill is to the music, so is Cama for the singing. For the wealth of the real old songs, that is the place and no mistake.

JOE: About the songs on this record now. Bádoírín Tír Niad, (That means The Boatman'): this boatman, he goes away, and the girl is grieving after him. She gives advice to all the girls never to set too much on one man because you might lose him, and him never come back. Then there's Skibereen, which is a place in Cork. This song was first made in Boston, Massachusetts, about a man who emigrated after the famine. He had been a '98 fighting man, you see, and his landlord burned his house and his wife perished in the snow. His son was two months old, and he took the son with him to America. When the boy is growing up, he tells him the reason they had to leave their home. Now, The Widow from Mayo is another emigration song about a widow woman who goes to the station to see her daughter off. She is going away to America — to Mexico, in fact, and the conversation goes on between them about the poverty that has made her leave and all the things she will miss and must leave behind. The story related to The Bogs of Shanaheever is about two boys who were forbidden to take a rich man's dogs coursing. While he is away they do so, and the greyhound named Bruce is killed. So they are forced to emigrate from Shanaheever, which is in Connemara. The Song of Mynish is the lament of a woman who dies far from her home. She dies in a hospital in Dublin, and she says she would walk all across Ireland if she could be buried in her home in Connemara, where she would be mourned over, and the ripples of the waves on the beach would keep her company, illuminated by the stars. That is a very beautiful song. Of course, The Banks of the Sweet Dundee tells its own tale.