Sleeve Notes

DAVID HAMMOND was born and bred in Belfast and the tang and quickness of that town's speech are in his voice. But a singing voice needs more than efficiency and definition, am the extra dimension in David's singing may come from a longing backward towards his Co. Derry and Co. Antrim ancestry, the line of the melody hankering for the line of what Louis MacNeice called "the pre-natal mountain". In his case, the, mountain would probably be Wild Slieve Gallen Brae, although he might also find iron The Banks of Claudy, a song which he learned at his mother's knee.

The style is personal and the personality northern, northern enough to be at home in Donegal where he has a house, or in "the green fields of Keady" in Co. Armagh (The Granemore Hare); but at the same time he can take his ease where the intonations of the Scottish and English traditions are more audible, in Bonny Woodgreen, for example, or in the company of The Gipsy Laddie, or with that crowd of roughs on The Giant's Causeway Tram.

David Hammond, in other words, is not conservative in his attitude to tradition or traditions, but radically creative. It is not the "purity" of the material that matters to him, not its ethnic culture quotient, its scholarly provenance: rather it is the scope it offers the voice for exultation or repining, for the play of feeling, for human touch. There is a moral vision implicit in the pitch of that voice, an impatience with systems, a calling into the realm of pure freedom. No wonder he sings the children's songs as if he owned them.

Because of the deep connections that have been discerned between folk-song and social protest or national feeling, many good singers go at their material with an attitude that is pious, if not solemn as it any revelling or rascality were a symptom of callous bourgeois individualism. Yet to raise a song as if it were a clenched fist is to underestimate the revolutionary power of song itself, its power to move and pleasure and affect those depth, of the personality where attitudes begin. Song, like the Sermon on the Mount, is a matter of revelation and celebration. So while there is nothing doctrinaire in the choice of material here, there is something more important,. an instinctive sympathy that appears in many guises; in the tenderness of the Cruel Mother, the pathos of Matt Hyland, and the tragic lift of The Bonnie Earl of Moray.

Any art is a matter of intuition and technique but perhaps Dónal Lunny's art has to be even more so. He must take a finished style and finish it again, replenish what is already replenished. The reciprocity and generosity, the heart in his work with David Hammond and the musicians, make this record memorable, convincing, valuable.

Seamus Heaney

My Aunt Jane: Probably the best loved of all Belfast street songs. The front parlour converted, the redbrick terrace house became the wee shop', the provender of tea, sugar, sweet milk, candles, potatoes, safety pins, soap and, of course, 'conversation lozenges'.

Fair Rosa: The beautiful girl sleeps for a hundred years. The sleep is induced by a sinister charm. probably a sleep-thorn, for the handsome prince 'cuts the hedges one by one' and wakens her. Belfast children, like children everywhere, believe in witches, fairies and magic.

Wild Slieve Gallen Brae: Several songs have been written around this mountain that stands in South Derry overlooking Lough Neagh I learned this one from Stewart Coleman in Ardboe, Co. Tyrone, its mood remote and indolent, perhaps even slightly surreal.

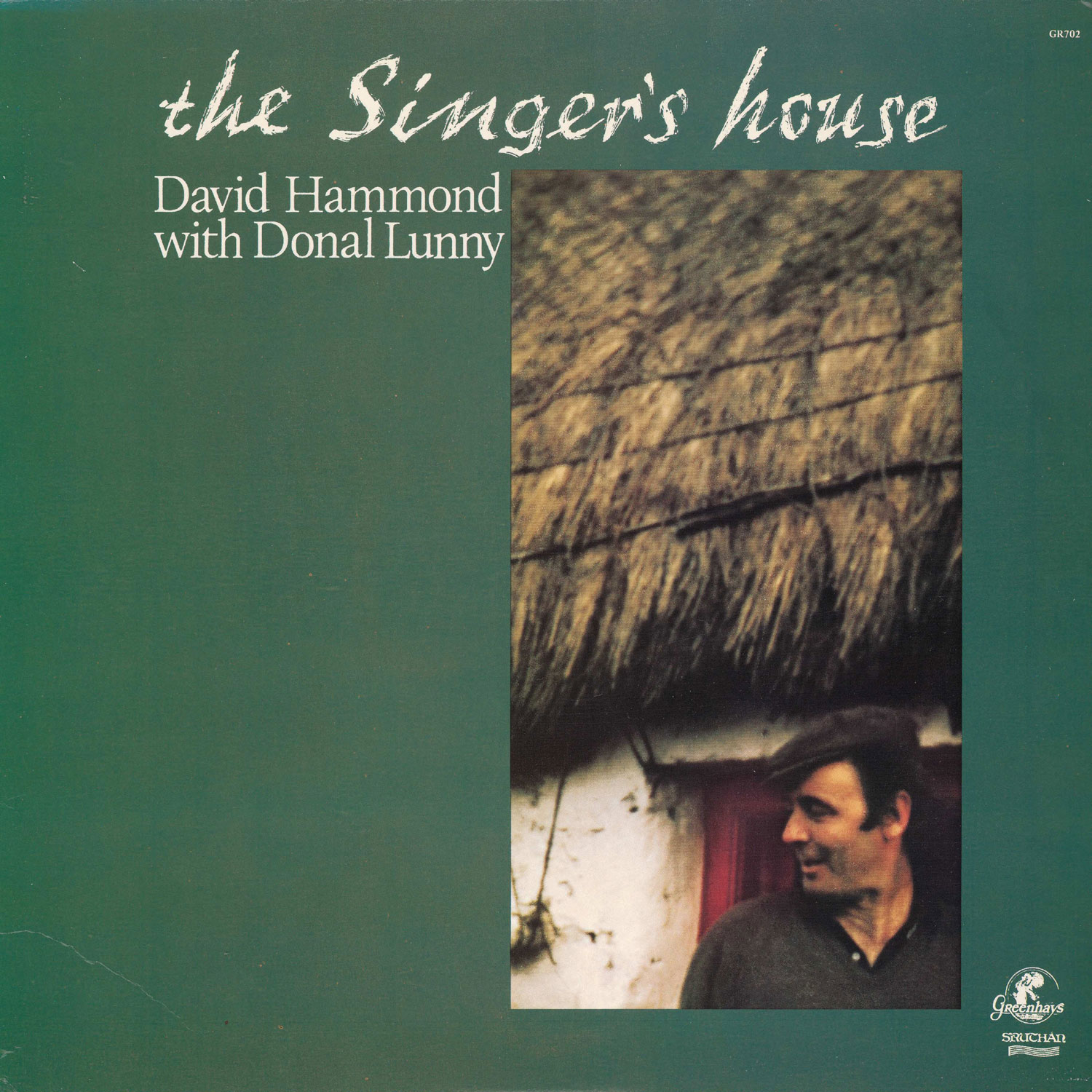

The Graemore Hare: This song celebrates the community around Keady in South Armagh, the men and their townlands, the lean hounds and the hare itself. Each man with one or two dogs joins his neighbours, they form a pack and the hunt is on. Needless to say, there are no horses nor pink coats. It's a territory that Basil Blackshaw, who painted the cover picture, understands better than most of us.

The Cruel Mother: A classical ballad, a tragic story, told laconically and impersonally, yet with a strong feeling for the glory and impermanence of human life. The form, a couplet with a refrain in alternate lines, derives from a singing-dance of the Middle Ages.

The Giant's Causeway Tram: This tram, the first hydroelectric tram in the world rattled for eight miles along the North Antrim coast, from Portrush past the White Rocks and Dunluce Castle, through Bushmills to the far-famed Giant's Causeway. It was something of a local institution an outlaw that never surrendered to conventions like comfort, punctuality and efficiency. In some ways it was a personification of the people it served Hugh Speers from Bushmills wrote the song after the tram finally creaked to a halt in 1949.

The Flower of Sweet Strabane: The beautiful Martha used to be renowned all over the north of Ireland. In verse after verse we hear the beautiful woman described but at the end of it all we know more about the writer than we do about Martha. I believe his name was McDonald (from another version) "… McDonald's fate you'll never see …"

The Bonnie Earl of Moray: James Stewart, son of Sir James Stewart of Doune, became Earl of Moray in consequence of his marriage with the eldest daughter and heiress of the Regent Moray. 'He was a comely personage, of a great stature, and strong of body like a kemp.'

In February 1592 the Earl of Huntly was commissioned by King James VI to apprehend and bring Moray to trial. Huntly burned Moray out of Donibrisstle House, on the Forth, and slew him. 'The death of the nobleman was universally lamented and the clamours of the people so great … that he king, not esteeming it safe to abide at Edinburgh, removed with the council to Glasgow …'

Bonnie Woodgreen: Woodgreen is a mill village near Ballymena in Co. Antrim, Sean MacReamoinn collected this song during a northern peregrination in the 1940s but I had to wait until 1964 before I heard it sung by Benedict Kiely, on his way by taxi to Cobh to take ship for New York. Later, in Ballymena, George McGuigan supplied me with these verses that date the song in the First World War. But there are other versions like the Scottish 'Bonnie Wood Ha' describing nineteenth century wars and reminding as that the theme is outside of time.

Matt Hyland: The parents are defied, the riches rejected, for the love of a labouring man. A pastoral theme that was common in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The Wee Falorie Man: Set apart, slightly mysterious, falorie (forlorn?), a first cousin to the English Gable 'oary Man. Gabriel Holy Man.

Green Gravel: A children's funeral game, dealing naturally with death and change, the 'letter' a reminiscence of beliefs in communion with the dead.

Fan-a-Winnow: A Belfast mill workers' song. Barney the band-tier maintained the leather belts that drove the spinning frames.

The Banks of Claudy: The story is pervasive. The girl does not recognise her lover when he returns from sea … he attempts to seduce her, saying her lover is dead … she remains true and he reveals himself she flies to his arms.

I heard this song from my mother, probably the first song I ever heard, and I was always enchanted with '… the royal king of honour upon the walls of Troy."

The Gypsy Laddie: The gypsies were expelled from Scotland by Art of Parliament in 1609. Afterwards many gypsies were hanged for remaining in the country. Their deaths made such an impression on the popular imagination that he gypsy became the hero of many traditional stories.

Some versions of this classical ballad associate the story with the Earl of Cassiliss ('Lord Castle' of the ballad) but there is little historical foundation for this. Anyway the historicity is irrelevant; this story could happen to anybody who neglects his wife.

David Hammond