|

|

Sleeve Notes

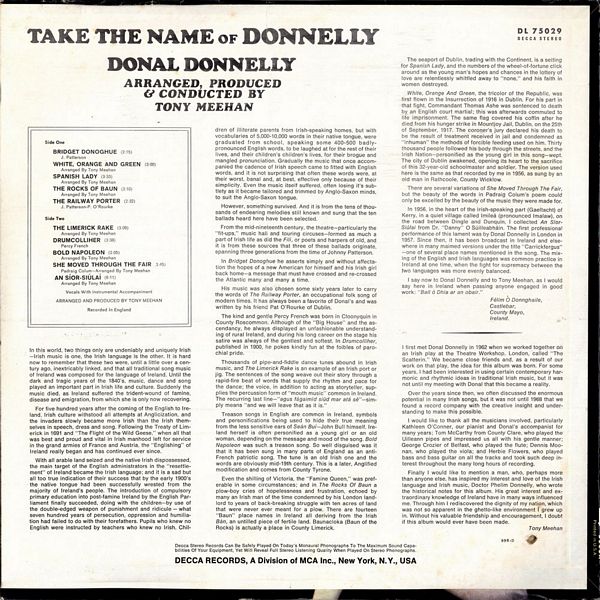

In this world, two things only are undeniably and uniquely Irish — Irish music is one, the Irish language is the other. It is hard now to remember that these two were, until a little over a century ago, inextricably linked, and that all traditional song music of Ireland was composed for the language of Ireland. Until the dark and tragic years of the 1840's, music, dance and song played an important part in Irish life and culture. Suddenly the music died, as Ireland suffered the trident-wound of famine, disease and emigration, from which she is only now recovering.

For five hundred years after the coming of the English to Ireland, Irish culture withstood all attempts at Anglicization, and the invaders slowly became more Irish than the Irish themselves in speech, dress and song. Following the Treaty of Limerick in 1691 and "The Flight of the Wild Geese," when all that was best and proud and vital in Irish manhood left for service in the grand armies of France and Austria, the "Englishing" of Ireland really began and has continued ever since.

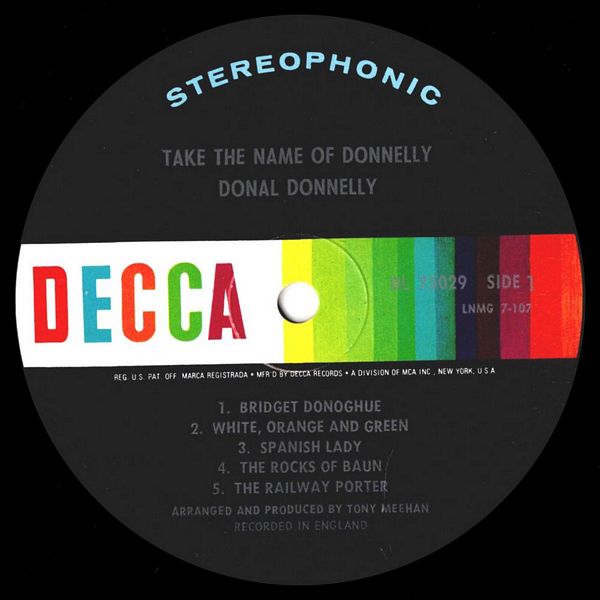

With all arable land seized and the native Irish dispossessed, the main target of the English administrators in the "resettlement" of Ireland became the Irish language; and it is a sad but all too true indication of their success that by the early 1900's the native tongue had been successfully wrested from the majority of Ireland's people. The introduction of compulsory primary education into post-famine Ireland by the English Parliament finally succeeded, doing with the children — by use of the double-edged weapon of punishment and ridicule — what seven hundred years of persecution, oppression and humiliation had failed to do with their forefathers. Pupils who knew no English were instructed by teachers who knew no Irish. Children of illiterate parents from Irish-speaking homes, but with vocabularies of 5,000-10,000 words in their native tongue, were graduated from school, speaking some 400-500 badly-pronounced English words, to be laughed at for the rest of their lives, and their children's children's lives, for their brogue and mangled pronunciation. Gradually the music that once accompanied the cadence of Irish speech came to fitted with English words, and it is not surprising that often these words were, at their worst, banal and, at best, effective only because of their simplicity. Even the music itself suffered, often losing it's subtlety as it became tailored and trimmed by Anglo-Saxon minds, to suit the Anglo-Saxon tongue.

However, something survived. And it is from the tens of thousands of endearing melodies still known and sung that the ten ballads heard here have been selected.

From the mid-nineteenth century, the theatre — particularly the "fit-ups," music hall and touring circuses — formed as much a part of Irish life as did the Filí, or poets and harpers of old, and it is from these sources that three of these ballads originate, spanning three generations from the time of Johnny Patterson.

In Bridget Donoghue he asserts simply and without affectation the hopes of a new American for himself and his Irish girl back home — a message that must have crossed and re-crossed the Atlantic many and many a time.

His music was also chosen some sixty years later to carry the words of The Railway Porter, an occupational folk song of modern times. It has always been a favorite of Donal's and was written by his friend Pat O'Rourke of Dublin.

The kind and gentle Percy French was born in Cloonyquin in County Roscommon. Although of the "Big House" and the ascendancy, he always displayed an unfashionable understanding of rural Ireland, and during his long career on the stage his satire was always of the gentlest and softest. In Drumcolliher, published in 1900, he pokes kindly fun at the foibles of parochial pride.

Thousands of pipe-and-fiddle dance tunes abound in Irish music, and The Limerick Rake is an example of an Irish port or jig. The sentences of the song weave out their story through a rapid-fire beat of words that supply the rhythm and pace for the dance; the voice, in addition to acting as storyteller, supplies the percussion form of "mouth music" common in Ireland. The recurring last line — "agus fágaimid siúd mar atá sé" — simply means "and we will leave that as it is."

Treason songs in English are common in Ireland, symbols and personifications being used to hide their true meaning from the less sensitive ears of Seán Bui — John Bull himself. Ireland herself is often personified as a young girl or an old woman, depending on the message and mood of the song. Bold Napoleon was such a treason song. So well disguised was it that it has been sung in many parts of England as an anti-French patriotic song. The tune is an old Irish one and the words are obviously mid-19th century. This a later, Anglified modification and comes from County Tyrone.

Even the shilling of Victoria, the "Famine Queen," was preferable in some circumstances; and in The Rocks Of Baun a plowboy cries of hopelessness and frustration, echoed by many an Irish man of the time condemned by his London landlord to years of back-breaking struggle with ten acres of land that were never ever meant for a plow. There are fourteen "Baun" place names in Ireland all deriving from the Irish Bán, an untilled piece of fertile land. Baunacloka (Baun of the Rocks) is actually a place in County Limerick.

The seaport of Dublin, trading with the Continent, is a setting for Spanish Lady, and the numbers of the wheel-of-fortune click around as the young man's hopes and chances in the lottery of love are relentlessly whittled away to "none," and his faith in women destroyed.

White, Orange And Green, the tricolor of the Republic, was first flown in the Insurrection of 1916 in Dublin. For his part in that fight, Commandant Thomas Ashe was sentenced to death by an English court martial; this was afterwards commuted to life imprisonment. The same flag covered his coffin after he died from his hunger strike in Mountjoy Jail, Dublin, on the 25th of September, 1917. The coroner's jury declared his death to be the result of treatment received in jail and condemned as "inhuman" the methods of forcible feeding used on him. Thirty thousand people followed his body through the streets, and the Irish Nation — personified as the young girl in this song — wept. The city of Dublin awakened, opening its heart to the sacrifice of this 32-year-old schoolmaster and soldier. The version used here is the same as that recorded by me in 1956, as sung by an old man in Rathcoole, County Wicklow.

There are several variations of She Moved Through The Fair, but the beauty of the words in Padraig Colum's poem could only be excelled by the beauty of the music they were made for.

In 1956, in the heart of the Irish-speaking part (Gaeltacht) of Kerry, in a quiet village called Imileá (pronounced Imalaw), on the road between Dingle and Dunquin, I collected An Síor-Siúlaí from Dr. "Danny" O Súilleabháin. The first professional performance of this lament was by Donal Donnelly in London in 1957. Since then, it has been broadcast in Ireland and elsewhere in many maimed versions under the title "Carrickfergus" — one of several place names mentioned in the song. The mixing of the English and Irish languages was common practice in Ireland at one time, when the fight for supremacy between the two languages was more evenly balanced.

I say now to Donal Donnelly and to Tony Meehan, as I would say here in Ireland when passing anyone engaged in good work: "Bail ó Dhia ar an obair."

Félim Ó Donnghaile,

Castlebar,County Mayo, Ireland

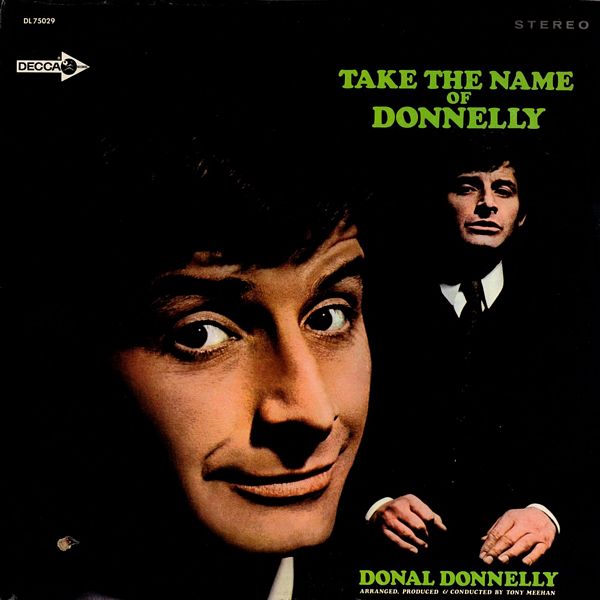

I first met Donal Donnelly in 1962 when we worked together on an Irish play at the Theatre Workshop, London, called "The Scatterin." We became close friends and, as a result of our work on that play, the idea for this album was born. For some years, I had been interested in using certain contemporary harmonic and rhythmic ideas in traditional Irish music, but it was not until my meeting with Donal that this became a reality.

Over the years since then, we often discussed the enormous potential in many Irish songs, but it was not until 1968 that we found a record company with the creative insight and understanding to make this possible.

I would like to thank all the musicians involved, particularly Kathleen O'Conner, our pianist and Donal's accompanist for many years; Tom McCarthy from County Clare, who played the Uilleann pipes and impressed us all with his gentle manner; George Crozier of Belfast, who played the flute; Dennis Moonan, who played the viola; and Herbie Flowers, who played bass and bass guitar on all the tracks and took such deep interest throughout the many long hours of recording.

Finally I would like to mention a man, who, perhaps more than anyone else, has inspired my interest and love of the Irish language and Irish music, Doctor Phelim Donnelly, who wrote the historical notes for this album. His great interest and extraordinary knowledge of Ireland have in many ways influenced me. Through him I rediscovered the dignity of my nation, which was not so apparent in the ghetto-like environment I grew up in. Without his valuable friendship and encouragement, I doubt if this album would ever have been made.

Tony Meehan