|

|

|

| more images |

Sleeve Notes

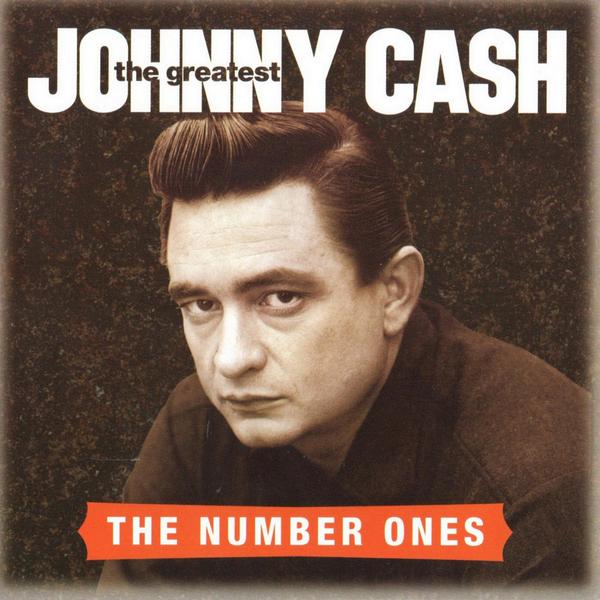

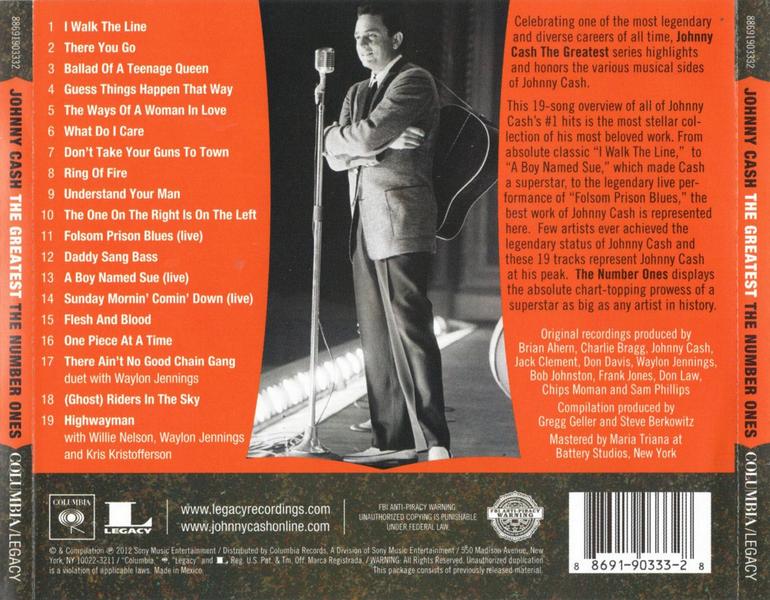

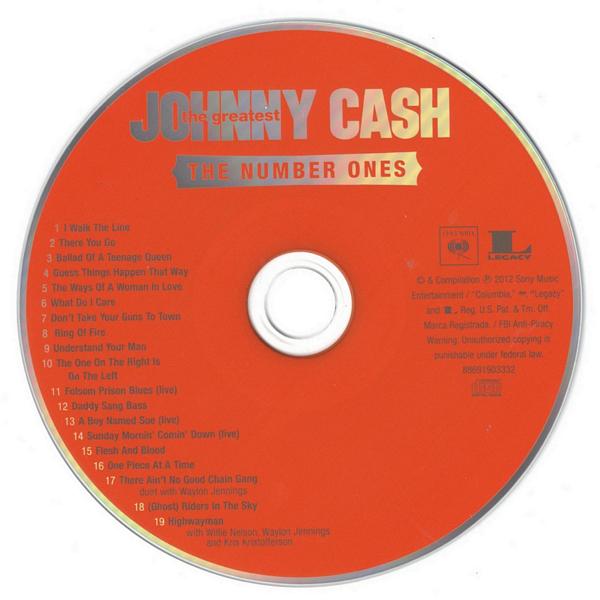

"From the time I was a kid, I didn't know that you're not supposed to like some kinds of music," Johnny Cash once told me. "I remember loving everything that came on the radio … But I started selling a few records and they had to have a category to put me in, I guess, so they called me country." Make no mistake about it: These nineteen number-one songs are country music in the best and broadest possible sense. But they don't conform to any stereotypical notion of country music. They much more reflect Cash's open-hearted attitude of "loving everything that came on the radio." That's the imaginative country he lived in, and that's embodied in every song on this set.

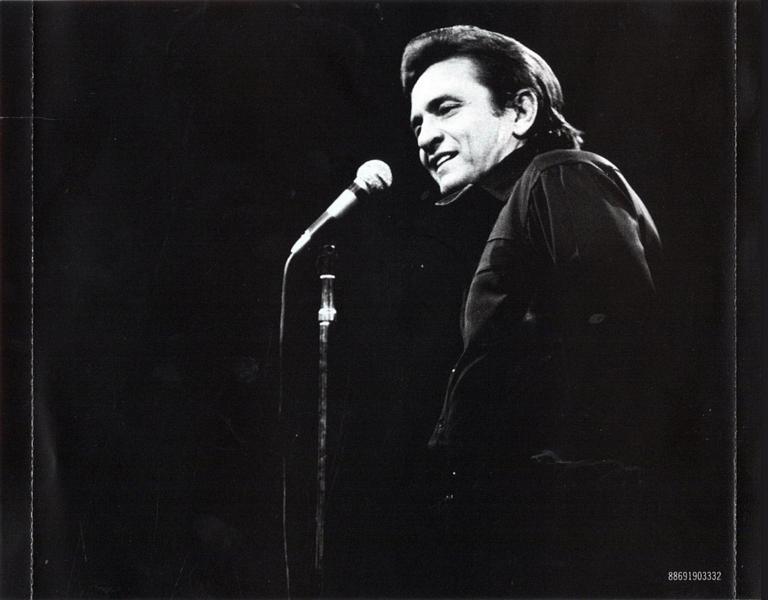

Cash's songs hit with such emotional force that it's occasionally possible to miss how much subtlety resides within them. Throughout the years — nearly three decades for the tunes on this collection — the voice remained the same: a baritone rumble that at times seemed indistinguishable from speech, a quality that lends it both authority and a powerful intimacy. It's a voice that never panders, nor seeks approval. Even melody is a grudging concession. The songs' tunes are invariably beautiful, sturdy and plainly elegant as Shaker furniture. But the voice is interested in communicating as directly as possible, and too much prettiness would be a distraction at best and an unnecessary compromise at worst.

Consequently, the voice works best in settings that are as minimal as its own carefully defined range, so that its effect is impervious to anything inessential. Whether Cash wrote the song or is interpreting it — a false distinction in his case, since he made every song he sang unmistakably his own — the words and their delivery are honest and straightforward. The feelings and ideas in the songs are as deep and rich as they come, but in Cash's hands they don't require fancy elaboration or floridness of any kind.

Indeed, Cash's vocal technique evokes the sparseness of Hemingway's writing. The suggestion is that a man so exacting in his use of words would not be speaking at all if what he had to say were not important, something demanding expression. And the listener's imagination is fully engaged, because what is not said in the lyric is as significant as what is. All the empty space between the words provides room to ponder the lyric and its ongoing meanings.

A title like "Guess Things Happen That Way" conveys so much about the confounding ways of the world, but in the unadorned language of everyday life. It's all there on the surface and it's bottomless in its depths. The complexity of a Johnny Cash performance lies in your thoughts about it once it's done and it takes up its permanent place in your memory. After that, each hearing of the song provides added insights, added poignancy and added pleasures.

Such are the joys of listening to this collection. That all nineteen tracks reached number one on the country charts provides eloquent testimony to the range of Cash's appeal. A song like "Ballad Of A Teenage Queen," produced by Jack Clement, is an obvious — and successful — attempt to frame Cash in a way that appealed to the burgeoning young rock & roll audience taking shape in the Fifties.

On the other end of the emotional spectrum stands "I Walk The Line," produced by Sam Phillips, which came out in 1956, just one year earlier. That son is as adult a statement as ever rose to the top of the charts. The opening line itself, "I keep a close watch on this heart of mine," suggests that within that heart lurk desires that are darker and more disruptive than pop songs typically admit. Resisting temptation, staying true, walking the line — those are grown-up concerns an emotional world away from the pastel malt-shop realm of "Ballad Of A Teenage Queen." But Cash could inhabit them both, and convincingly convey them to his audience. It's a quality that's easy to take for granted, but it's no less rare or special for that.

"A Boy Named Sue," a number one hit in 1969 is the song that made Cash a superstar, one of the best-selling artists in the world at a moment when he was competing with the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan and all of the redoubtable Motown and Stax acts. "A Boy Named Sue" is often compared with Chuck Berry's "My Ding-a-Ling," which is to say it's dismissed as a novelty song whose primary virtue is that it brought mainstream success to an edgy, deserving artist.

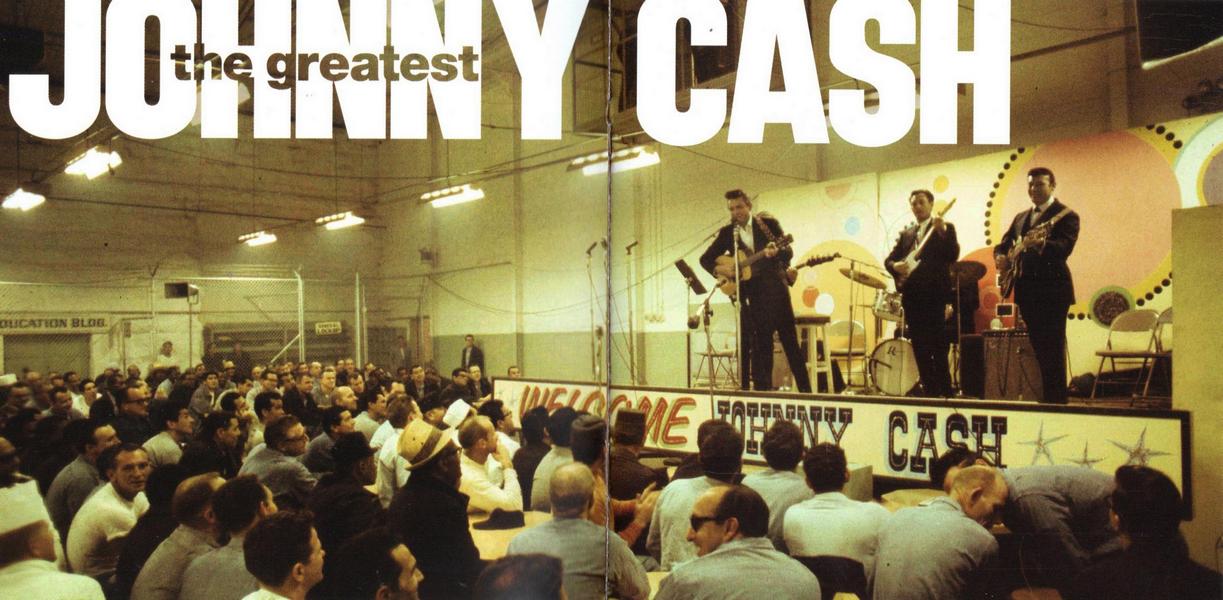

But such an assessment gives the song far less than it's due. It must be remembered, first of all, that "A Boy Named Sue" was written by Shel Silverstein, hardly someone whose writing pandered to mainstream tastes. Second, Cash debuted the song in front of an audience of prisoners at San Quentin in 1969, an audience for whom the song's comic relief was both welcome and deserved. Finally, the song's playful and ultimately sensitive look at gender confusion was a timely, resonant and even controversial subject for a country artist, let alone one performing at a prison. Those were the days when long hair on males would routinely prompt the taunting question, "Is that a boy or a girl?" — and nowhere more so than in the South. That the young man who bears a girl's name is tough enough to fight his own father to the brink of death (the emotionally fraught generation gap being another tense issue of those times) only to reach a mutual understanding and make up sent a powerful, if subliminal, message. It's hard to imagine another artist who could have walked those fault lines with a fraction of Cash's humor and grace.

Recording in a prison also was one of the ways that Cash deepened themes in country music that had too often hardened into cliches. Songs about jail might have been a well-worn country genre, but recording in a prison was something that had not been done before. Playing in front of a crowd whose real lives put flesh-and-blood on those themes was a daring move on Cash's part. As a result, the emotional extremes of "Folsom Prison Blues," the swaggering defiance of ‘I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die' and the vulnerable yearning for freedom that aches as the prisoner hears the train roll by pass a reality test that few artists would have had the courage to subject themselves or their work to. It's another example of the divisions that Cash's artistry and persona are able to bridge.

The same can be said of the indelible "Don't Take Your Guns To Town," which Cash himself wrote and which became a number-one hit in 1958. The song rivals Merle Haggard's "Mama Tried" for transcending the limitations of the genre that gave it birth: the grieving mother whose sage advice is ignored, leading to tragedy. As always, Cash's vocal understates the events of the song, which move forward with the narrative momentum of a brilliant, three-minute western film. The Tennessee Two, Cash's famed backing band consisting of Luther Perkins on guitar and Marshall Grant on upright bass, truly distinguishes itself here. The moods of the song alter with each rhythmic shift, and when the instruments drop out entirely and Cash sings unaccompanied, the emotional impact packs the punch of an orchestra, even though his singing couldn't be more introspective and restrained. It's a masterful performance that includes nothing extraneous and does nothing to call undue attention to itself. When you've got a great song, you simply let it speak for itself.

Another two tracks that make an important point merely by their proximity are "Ring Of Fire," a number one hit in 1963, and "Understand Your Man," which hit the top of the charts later that same year. "Ring Of Fire," of course, was written by Merle Kilgore and June Carter, who would later marry Johnny Cash and form one of the most romantic unions in all of popular music. Carter wrote the song about her feelings for Cash, which were overwhelming her because they had come at what she described as not being "a convenient time." Both Carter and Cash were both married to other people. She described the feeling to me this way: "I thought, 'I can't fall in love with this man, but it's like fire. It's just like a ring of fire.' That's how the song started." Cash shared those feelings, but ultimately the song described a "sweet fire," he said. "The ring of fire that I found myself in with June Carter was the fire of redemption," he told me. "It cleansed. It made me believe everything was alright because it felt so good."

Then there's the unadulterated bitterness of "Understand Your Man." Cash, who wrote the song, took inspiration for it from Bob Dylan's "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right." Cash was one of Dylan's earliest supporters, a generous appreciation that Dylan never forgot. Cash took the submerged anger of Dylan's tune, and brought it right to the forefront. The song is a rare instance of Cash's unmitigated expression of anger towards a woman in a relationship. His stoic nature typically meant that the listener would have to hear between the lines to tap into such emotions. But not in this instance.

Johnny Cash embodies such an outsized personality that, in an abstract sense, the idea of his working with others in any role but band leader seems absurd. Wouldn't he simply overwhelm any collaborative situation? The fact, however, is that Cash loved duets and group efforts and was able to bring the best of his talents to such partnerships while allowing more than enough room for his fellow musicians to shine as well. You get a brief taste of Cash's love of family-style music making on Carl Perkins's "Daddy Sang Bass," a variation on the Carter Family's "Will The Circle Be Unbroken." Cash, of course, would marry June Carter, and her family members would be part of the Cash touring band for many years.

On "There Ain't No Good Chain Gang" Cash duets with Waylon Jennings, who was like family to Cash. Cash once described Jennings to me as "as close as a brother could be. Just couldn't be any closer." The two men roomed together in Nashville in their younger, wilder days, and it was luck rather than virtue that prevented their living out the scenario this song describes. Back then being outlaws was a lifestyle for them, not a musical genre. Cash laughingly described Jennings' seductive growl as "I love you, but not all that much. I love you, but don't tell anybody." Jennings is a boomier, more dramatic singer than the more restrained Cash, but the two men complement each other's talents and curb each other's excesses. In other words, they realize exactly what a duet is supposed to accomplish.

"Highwayman," the final song, provided a name both for the supergroup that recorded it and the band's terrific debut album. On this affecting performance, Cash assumes a comfortable place amid his heroic country peers Jennings, Willie Nelson and Kris Kristofferson (who, of course, also wrote the immortal "Sunday Mornin' Comin' Down" on this set). The song is a spacious, cinematic tone poem composed by Jimmy Webb, a songwriter who can proudly stand shoulder to shoulder with any of the giants performing here. Chips Moman, the song's producer, is yet another titan, and his work perfectly captures the mythic quality of the song and of the Highwaymen themselves.

Quoting Johnny Cash approvingly, Willie Nelson once told me that "a hit covers a multitude of sins!" It's a perfect Cash aphorism — funny, Biblical and pragmatic as can be. What he means is that you create music for people to hear and enjoy, and you can't argue with music that accomplishes exactly that. When you manage to do that over an extended period of time, that's an achievement of a very high order. Different as they are from each other, each of these songs hit the number one spot because people found something in them to love. Part of what they found is all the talent, all the humanity and all the conviction, that Johnny Cash represents. And with this collection, we are all given a splendid opportunity to discover and rediscover those peerless qualities again. And again.

Anthony DeCurtis

Song Notes