|

|

|

|

| more images |

22 minutues

Sleeve Notes

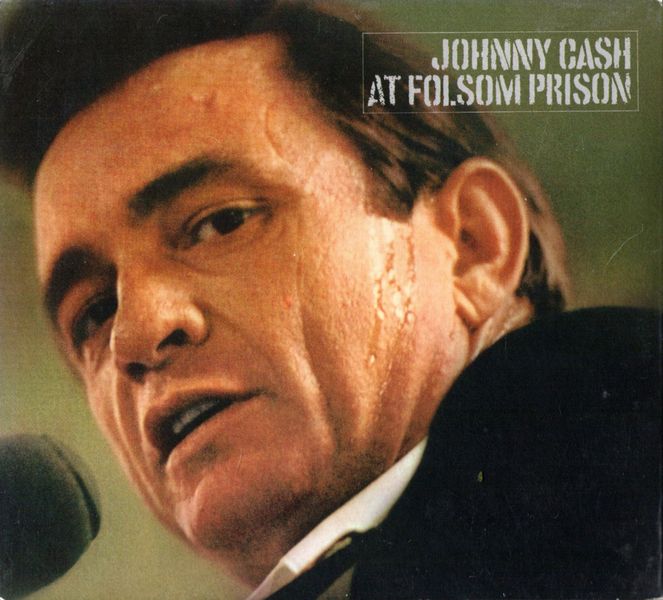

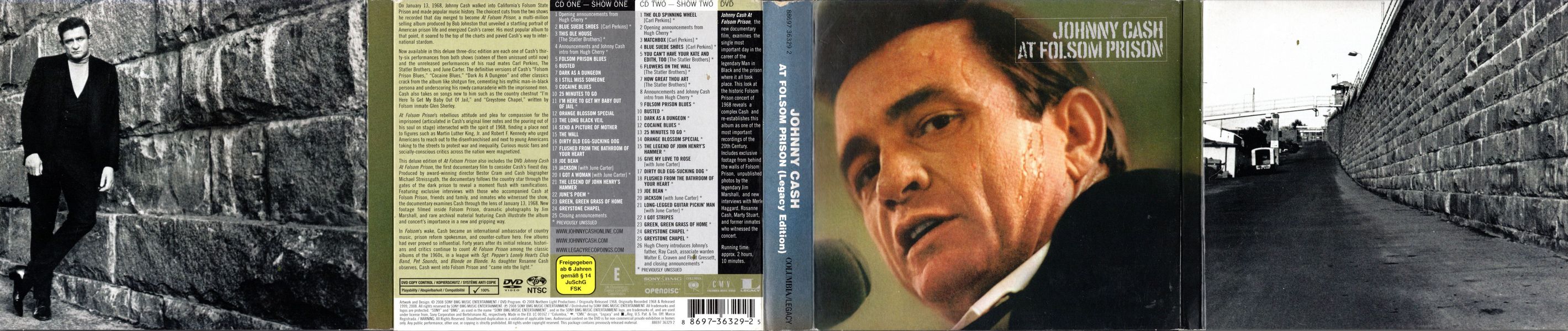

On January 13, 1968, Johnny Cash walked into California's Folsom State Prison and made popular music history. The choicest cuts from the two shows he recorded that day merged to become At Folsom Prison, a multi-million selling album produced by Bob Johnston that unveiled a startling portrait of American prison life and energized Cash's career. His most popular album to that point, it soared to the top of the charts and paved Cash's way to international stardom.

Now available in this deluxe three-disc edition are each one of Cash's thirty-six performances from both shows (sixteen of them unissued until now) and the unreleased performances of his road mates Carl Perkins, The Statler Brothers, and June Carter. The definitive versions of Cash's "Folsom Prison Blues," "Cocaine Blues," "Dark As A Dungeon" and other classics crack from the album like shotgun fire, cementing his mythic man-in-black persona and underscoring his rowdy camaraderie with the imprisoned men. Cash also takes on songs new to him such as the country chestnut "I'm Here To Get My Baby Out Of Jail," and "Greystone Chapel," written by Folsom inmate Glen Sherley.

At Folsom Prison's rebellious attitude and plea for compassion for the imprisoned (articulated in Cash's original liner notes and the pouring out of his soul on stage) intersected with the spirit of 1968, finding a place next to figures such as Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy who urged Americans to reach out to the disenfranchised and next to young Americans taking to the streets to protest war and inequality. Curious music fans and socially-conscious critics across the nation were magnetized.

This deluxe edition of At Folsom Prison also includes the DVD Johnny Cash At Folsom Prison, the first documentary film to consider Cash's finest day. Produced by award-winning director Bestor Cram and Cash biographer Michael Streissguth, the documentary follows the country star through the gates of the dark prison to reveal a moment flush with ramifications. Featuring exclusive interviews with those who accompanied Cash at Folsom Prison, friends and family, and inmates who witnessed the show, the documentary examines Cash through the lens of January 13, 1968. New footage filmed inside Folsom Prison, dramatic photographs by Jim Marshall, and rare archival material featuring Cash illustrate the album and concert's importance in a new and gripping way.

In Folsoms wake. Cash became an international ambassador of country music, prison reform spokesman, and counter-culture hero. Few albums had ever proved so influential. Forty years after its initial release, historians and critics continue to count At Folsom Prison among the classic albums of the 1960s, in a league with Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, Pet Sounds, and Blonde on Blonde. As daughter Rosanne Cash observes. Cash went into Folsom Prison and "came into the light."

Johnny Cash At Folsom Prison, the new documentary film, examines the single most important day in the career of the legendary Man in Black and the prison where it all took place. This look at the historic Folsom Prison concert of 1968 reveals a complex Cash and re-establishes this album as one of the most important recordings of the 20th Century.

Includes exclusive footage from behind the walls of Folsom Prison, unpublished photos by the legendary Jim Marshall, and new interviews with Merle Haggard, Rosanne Cash, Marty Stuart, and former inmates who witnessed the concert.

Folsom Prison Blues

The culture of a thousand years is shattered with the clanging of the cell door behind you. Life outside, behind you immediately becomes unreal. You begin to not care that it exists. All you have with you in the cell is your bare animal instincts.

I speak partly from experience. I have been behind bars a few times. Sometimes of my own volition sometimes involuntarily. Each time, I felt the same feeling of kinship with my fellow prisoners.

Behind the bars, locked out from "society," you're being re-habilitated, corrected, re-briefed, re-educated on life itself, without you having the opportunity of really reliving it. You're the object of a widely planned program combining isolation, punishment, taming, briefing, etc., designed to make you sorry for your mistakes, to re-enlighten you on what you should and shouldn't do outside, so that when you're released, if you ever are, you can come out clean, to a world that's supposed to welcome you and forgive you.

Can it work??? "Hell NO." you say. How could this torment possibly do anybody any good … But then, why else are you locked in?

You sit on your cold, steel mattressless bunk and watch a cockroach crawl out from under the filthy commode, and you don't kill it. You envy the roach as you watch it crawl out under the cell door.

Down the cell block you hear a steel door open, then close. Like every other man that hears it, your first unconscious thought reaction is that it's someone coming to let you out, but you know it isn't.

You count the steel bars on the door so many times that you hate yourself for it. Your big accomplishment for the day is a mathematical deduction. You are positive of this, and only this: There are nine vertical, and sixteen horizontal bars on your door.

Down the hall another door opens and closes, then a guard walks by without looking at you, and on out another door.

"The son of a … "

You'd like to say that you are waiting for something, but nothing ever happens. There is nothing to look forward to.

You make friends in the prison. You become one in a "clique," whose purpose is nothing. Nobody is richer or poorer than the other. The only way wealth is measured is by the amount of tobacco a man has, or "Duffy's Hay" as tobacco is called.

All of you have had the same things snuffed out of your lives. Every thing it seems that makes a man a man. a woman, money, a family, a job, the open road, the city, the country, ambition, power, success, failure — a million things.

Outside your cellblock is a wall. Outside that wall is another wall. It's twenty feet high, and its granite blocks go down another eight feet in the ground. You know you're here to stay, and for some reason you'd like to stay alive — and not rot.

So for the fourth time I have done so in California, I brought my show to Folsom. Prisoners are the greatest audience that an entertainer can perform for. We bring them a ray of sunshine in their dungeon and they're not ashamed to respond, and show their appreciation. And after six years of talking I finally found the man who would listen at Columbia Records. Bob Johnston believed me when I told him that a prison would be the place to record an album live.

Here's the proof. Listen closely to this album and you hear in the background the clanging of the doors, the shrill of the whistle, the shout of the men … even laughter from men who had forgotten how to laugh.

But mostly you'll feel the electricity, and hear the single pulsation of two thousand heartbeats in men who have had their hearts torn out, as well as their minds, their nervous systems, and their souls.

Hear the sounds of the men, the convicts all brothers of mine with the Folsom Prison Blues.

Johnny Cash

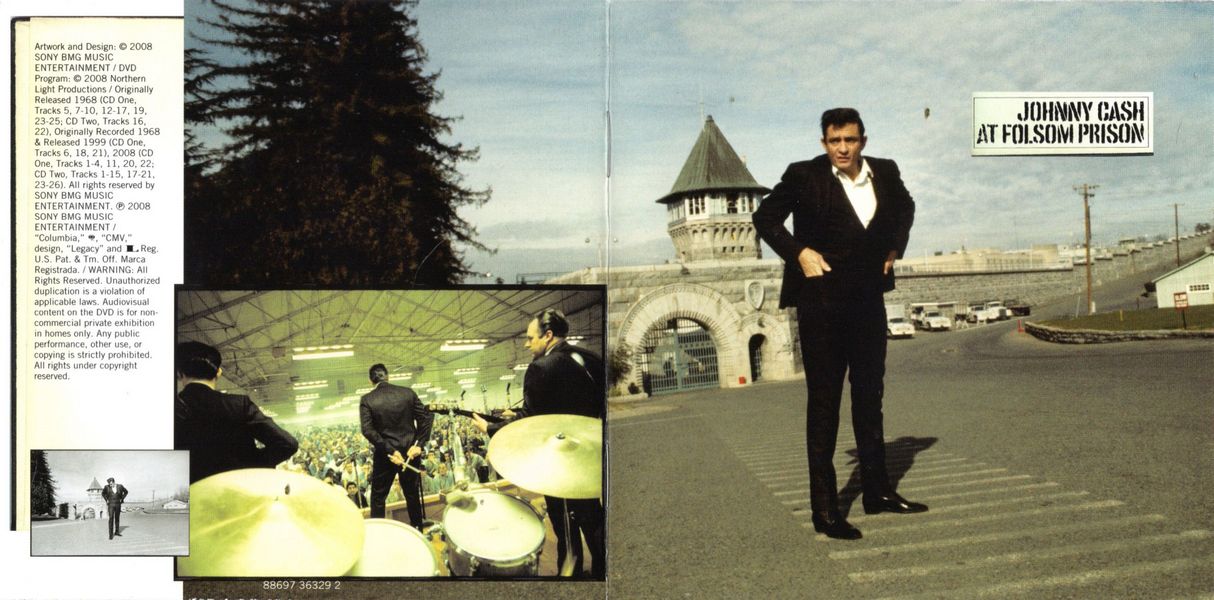

Gray clouds filled the skies above Folsom State Prison on the morning of January 13, 1968, darkening Johnny Cash's grimace as he walked through the tall iron gates of the granite city to a cavernous dining hall, where he planned to record two shows in front of Folsom's inmates. Rock and roll photographer Jim Marshall snapped the country star and his troupe as they marched past a few prison guards and the massive housing units in which life was just beginning to stir. In Marshall's photos, they resemble a funeral procession, everybody in black, everybody grim.

Among the mournful were Cash's Tennessee Three — bassist Marshall Grant, drummer W.S. "Fluke" Holland, and guitarist Luther Perkins — duet partner June Carter, The Statler Brothers, and rockabilly great Carl Perkins, who would open the show and also join the Tennessee Three, mixing in his thrilling guitar licks. They all had played prisons for years — Huntsville in Texas, San Quentin in San Francisco, and even Folsom, which they had first visited in 1966. The musicians knew the routine — give the murderers, rapists, and larcenists a message of hope and a moment's escape with blistering prison songs and spicy repartee. But this date demanded performances for album release delivered in a cold prison cafeteria. Perhaps that explained the worried faces.

Few of Cash's associates and musicians remember that he recorded two concerts that day in the prison, and even his most ardent fans never knew. The At Folsom Prison album seemed so obstinately self-contained, the first and last word on Cash's raucous communion with the imprisoned. But Cash's producer, Bob Johnston, needed two shows. He scheduled them for 9:40 a.m. and 12:40 p.m., guessing that he'd have to piece together the album from nuggets scattered throughout both performances.

As it happened, the earlier show blazed. "The guy was on fire," exclaims Cash's protege Marty Stuart, who owned the album as a ten-year-old child. "He had been there enough times, and he had rehearsed that prison-singer scenario, the jailhouse scenario, enough to really have his act down. He was cocky. He was at the top of his game. I mean he had heaven all over him. He was just twinkling." In the later show, Cash struggled to recapture the dynamism of the earlier show, so Johnston left most of it off the original album. But to hear the later show, available now for the first time, is to understand Cash's heart and his absolute commitment to the prisoners. He never stopped loving them, even as his energy drained.

Just like the original release of At Folsom Prison (1968), we hear Cash charge through set lists that invoke the prisoners' experiences and attitudes — "Folsom Prison Blues," "Busted," "25 Minutes To Go," "The Legend Of John Henry's Hammer." But in this new At Folsom edition we hear him stumble, too — flubbing the lyrics to the country chestnut "I'm Here To Get My Baby Out Of Jail," which Cash had never recorded before, futilely coughing to regain his voice after too many songs sung, and hitting sour notes on his "Orange Blossom Special" harmonica. For the benefit of the recording, yet unheard until now, he egged on the prisoners: "Wanna be on records? Go ahead and say something nice." The audience erupted in hoots and profanity. Arriving at the crowning moments in both shows, Cash hammered out "Greystone Chapel," an ode to the granite building that was and still is Folsom Prison's spiritual refuge, written by inmate Glen Sherley, an inveterate bank robber who would become a major character in the Folsom story. The audience clamored as three times Cash grappled with "Greystone Chapel," searching for a suitable take. "Last night was the first time I heard this song. The first time I tried to sing it," he confessed to his second audience. "It might have come off a little bit better on the first show today than I can do it now. I don't know until I try." Critics have long praised At Folsom's rawness. This new release shows how raw it really was.

Recorded days before the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, and a few months before the shocking assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, the album's performances and Cash-penned liner notes urged listeners to remember the caged men, much like King shone the spotlight on disenfranchised blacks and the voiceless poor. The album also tapped into the yearnings of late sixties music fans around the world who wanted from their music more viscosity, more depth, more reality, more rebellion. At Folsom Prison gave it to them — songs performed with unrelenting passion, a performer who would let nobody stand in his way, and a look at a failing prison system. In his liner notes, Cash addressed the imprisoned and their difficult plight — "You're the object of a widely planned program combining isolation, punishment, training, briefing, etc., designed to make you sorry for your mistakes, to re-enlighten you on what you should and shouldn't do outside, so that when you're released, if you ever are, you can come out clean, to a world that's supposed to welcome and forgive you. Can it work? 'Hell no,' you say."

Like Truman Capote's In Cold Blood (1965) and Frank Sinatra's role as Angelo Maggio in From Here To Eternity (1953), At Folsom Prison is a climax in a career. On that day, as daughter Rosanne Cash sees it, Cash came into the light. "That was the hinge on which a whole door opened to something else. And also kind of quantified who he was as an artist. It was so important; I don't think you can overestimate the importance of it."

At Folsom Prison traces its roots to the early 1950s when airman John R. Cash absorbed Crane Wilbur's Inside The Walls Of Folsom Prison, a movie that The New York Times dismissed as an "uninspired melodrama." But Cash was hooked — and inspired. "It was a violent movie," he recalled, "and I just wanted to write a song that would tell what I thought it would be like in prison." Returning to his barracks at Landsberg Air Force Base in West Germany, he began scribbling the lyrics to "Folsom Prison Blues" with its famous line, I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die. He admitted later that he adapted that line from Jimmie Rodgers' "Blue Yodel #1 (T For Texas).'' But he hadn't stopped there. On an old turntable belonging to one of his bunkmates, he'd been listening to "Crescent City Blues" by Gordon Jenkins whose arrangements and conducting would polish many of Frank Sinatra's records in the 1960s. A white man's lament in the vein of "0l' Man River" and "Stormy Weather," "Crescent City Blues" provided many of the verses and the complete lyrical rhythm for Cash's "Folsom Prison Blues." Despite its mongrel origins, "Folsom" became the quintessential Cash song when he finally recorded it for Sun Records in 1955, crammed with metaphors of loneliness and longing and stark allusions to that favorite of all Cashian symbols — the train. It spent twenty weeks on the country charts in 1956.

In the decade after hitting paydirt with "Folsom Prison Blues," as Cash continued his success with "I Walk The Line," "Ring Of Fire" and other enormous hits, he decided that "Folsom" deserved a homecoming at California's Folsom State Prison, and that it should be recorded. In retrospect, the idea seems so obvious — marrying the song and the prison in front of a wild audience — but few shared Cash's vision. As he mentioned in his liner notes, he had tried for six years to persuade Columbia Records to green light a prison recording, but the doors refused to open. "He had this impulse to do it," observes Rosanne. "And he had to go to bat. He had to fight people to get to do it and that's in the nature of a great artist, to see something where other people don't see it. I don't think he knew that it would be as successful as it was, but I think he knew it was important to do." The doors finally swung open in late 1967 when maverick producer Bob Johnston took charge of the company's Nashville operations.

Like any dramatic climax, Cash's followed a painful rising action. During the six years preceding the release of At Folsom, Cash had faltered — drug addiction mired him, relationships with his wife and children were torn, record sales lagged, and by 1967 half of his shows were no-shows, which alienated concert promoters all over the nation. Throughout the decade, despite creating some of his best work — concept albums that dealt with working people, the American Indian, the West and other topics — Cash teetered near death. He'd become, as Cash himself described, a "devastated, incoherent, unpredictable, self-destructive, raging terror."

Ironically, Cash somehow saw through his troubles to follow new artistic directions that laid the groundwork for At Folsom's million-selIing success. In the early 1960s, he'd begun exploring the folk revival movement, Of course, Cash probably helped spark the movement with late 1950s recordings that harked back to his own rural childhood — "Five Feet High And Rising" and "Pickin' Time" — and his re-workings of old folk songs such as "Grandfather's Clock," "Frankie And Johnny," and "Give My Love To Nell." By 1964, he had befriended Bob Dylan, guitar pulling with him at the Newport Folk Festival, recording his songs "Mama You've Been On My Mind" and "It Ain't Me Babe," and borrowing heavily from "Don't Think Twice It's All Right" to come up with 1964's "Understand Your Man." With the release of At Folsom Prison 1968, young record buyers familiar with Cash's link to Dylan, who had grown tired of AM radio pop and formulaic psychedelic concoctions, gave him a try.

Those young people represented the so-called "underground market." They gravitated to FM radio stations and their delicious playlists that slotted Moby Grape next to Merle Haggard next to Miles Davis. And they read Rolling Stone magazine. On the eve of At Folsom's release, Rolling Stone editor and publisher Jann Wenner in a discussion of the album placed Cash and Dylan right next to each other in what amounted to a loud endorsement of Cash that was read from the Bancroft Strip to Washington Square. "They are both master singers, master story tellers and master bluesmen. They share the same tradition, they are good friends, and the work of each can tell you about the work of the other." Soon alternative weeklies such as The Village Voice in New York, The Free Press in Washington, D.C., and The Seed in Chicago took Wenner's cue and endorsed Cash's new album. "Cash's voice is as thick and gritty as ever, but filled with the kind of emotionalism you seldom find in rock . . . ," wrote Richard Goldstein in The Voice. "His songs are simple and sentimental, his message clear. . . . The feeling of hopelessness — even amid the cheers and whistles — is overwhelming. You come away drained, as the record fades out to the sound of men booing their warden, and a guard's gentle, but deadly warning, 'Easy now.' Talk about magical mystery tours."

Many of Goldstein's readers may have seen At Folsom's realism as a snapshot of what their lives might be like behind bars. The 1960s produced a class of political prisoners who had protested segregation, war, poverty and other issues and found themselves in prison because of it. Pacifist Philip Berrigan and Freedom Rider Diane Nash were among the prominent Americans to spend time in prisons and jails because of their beliefs, but right behind them lingered scores of anonymous young people, many of them FM-listening children of the middle class, who were weighing prison against freedom. Should I burn my draft card? Should I cross police lines? Should I march in defiance of court orders? Is At Folsom what prison's really like? Hmm.

By the summer of 1968, the album bubbled up from the underground into the establishment as pop radio and mainstream magazines drooled over Cash and his prison repertoire. "Johnny Cash sings these songs with the deep baritone conviction of someone who has grown up believing he is one of the people that these songs are about," wrote Alfred Aronowitz in Life. At Folsom supercharged Cash's career, and in the process, validated his art and stole his attention from the drugs. As it scaled the charts and attracted reams of press coverage, promoters who'd dismissed him as a no show or restricted his bookings to county fairs and small municipal auditoriums now placed him in fancy amphitheatres and big-city arenas. "When this album came out, it just turned everything in our lives around," says Marshall Grant. "Our career was turned around. John was becoming what he deserved. It never would have happened if it hadn't been for [At Folsom]." Documentarians flocked around him and television producers soon followed. ABC-TV offered him his own weekly show thanks to the excitement At Folsom generated, and Columbia recorded Live At San Quentin, the wildly popular follow-up prison album that At Folsom had mid-wifed. Indeed Cash rose to the halls of establishment entertainment and cruised on the At Folsom-generated momentum for at least a decade.

At Folsom also fueled Cash's undying association with darkness in the human condition. As far back as the 1950s, brooding hits such as "I Walk The Line" and "Give My Love To Rose" hinted at some Faustian deal and a handful of public run-ins with the law, too, suggested as much. But nothing brushed Cash with darkness as broadly as At Folsom Prison, mostly due to its loud suggestion that Cash had done hard time. Could any listener be blamed for thinking it? Hadn't he sounded devilishly conspiratorial with the men whom he entertained? Hadn't they cheered him like a brother? Didn't his voice sound gallows grave and the scar on his cheek look like a knife wound? "For a while when I was a kid, I even thought he did," says Rosanne. "I remember thinking, 'Did he go to prison?' Reading some of this stuff and thinking, 'When did that happen? Did my mom keep it a secret from us?,' and then realizing that it was part of this mythmaking thing." The Grammy®-winning liner notes that Cash wrote only fueled the myth — "I have been behind bars a few times," wrote Cash. "Sometimes of my own volition — sometimes involuntarily. Each time, I felt the same feeling of kinship with my fellow prisoner." For the rest of his years, he uncomfortably lived with the myth.

The men who had awakened that morning in the dull January light inside Folsom gathered in the cafeteria for the concert because very few artists of Cash's stature ever came calling. "This was such a delicacy," says inmate Millard Dedmon, "and such a good thing to have anyone come in. And it doesn't matter whether he's a white boy with a country music band or whether he was a black boy with a blues band. It didn't matter a whole lot. You know what I mean? The thing was, we had somebody come in to us. Somebody from the outside. And in the case of Johnny Cash, here was a man who was evidently interested in the environmental situation there at Folsom Prison because he wrote ['Folsom Prison Blues']. I mean it's all said right there in the song."

Each song Cash reeled off that day spoke his understanding of prison life — "Dark As A Dungeon," "I Still Miss Someone," "Cocaine Blues," "Send A Picture Of Mother" — songs that need no new introduction here, but which acquired new life when Cash performed them at Folsom. Each song described confinement in some sense — in a coal mine, in love, in poverty — making clear to the men that they weren't the only ones imprisoned. And between songs, he conversed with the men on their level, grumbling about wardens and dishing out off-color jokes. "You know," continues Dedmon, "you started watching him play that guitar, I mean he was the kind of guy who said, 'Man I'm doing this for you. And I'm giving it all I have.' And you appreciate it. If anything lives inside you, you appreciate that. You say, 'This man is performing for me or for us.' You know what I mean? And he was good at that."

No moment showed the solidarity Dedmon sensed more than when Cash and the band turned to Glen Sherley's "Greystone Chapel." Rev. Floyd Gressett, who counseled Folsom inmates and pastored Cash's church in Ventura, California, had slipped Sherley's song to Cash, and the night before the concert in a Sacramento hotel the singer rehearsed it for the first time. The next day, the men in denim cheered it like no other song Cash performed for them. It was their theme, told of their lives. You wouldn't think that God had a place here at Folsom/But he's freed the soul of many a lost man.

"Greystone Chapel" authenticated the album, just as the album itself licensed Cash to speak out on prison reform. Indeed, after At Folsom's release, the singer plunged into the prison reform movement. He gave countless press interviews dealing with prison, lobbied President Richard Nixon on the subject, and attacked backward prison conditions on his ABC television show. As the bloody Soledad Brothers rescue attempt in California and the Attica Prison riot in New York grabbed headlines in the early 1970s, reporters and politicians hungry for answers continued to turn to Cash. "Unless people begin to care, all of the money in the world will not help," Cash told a U.S. Senate sub-committee in 1972. "Money cannot do the job. People have got to care in order for prison reform to come about." In Cash's wake, bluesman B.B. King joined the prison reform dialogue by recording Live In Cook County Jail and organizing an advocacy group for ex-cons, and then Bob Dylan championed the cause of Rubin "Hurricane" Carter, the ex-boxer from New Jersey wrongly convicted of a triple murder.

But Cash took his commitment one step further. In interview after interview, he'd repeated that if we all took the time to care, our prisons would be empty and our streets safer. Glen Sherley became his proof. While the prison songwriter remained behind bars, Cash trumpeted his talent wherever he traveled. He implored one of his heroes, Eddy Arnold, to record Sherley's "Portrait Of My 'Woman" and he arranged for Mega Records to release a prison album by Sherley, which charted in 1971. And then with the help of California Gov. Ronald Reagan and evangelist Billy Graham, he won Sherley's parole, promising the California Department of Corrections that his charge would contribute to society by writing for his Nashville publishing company and performing with his troupe. Sherley's freedom exhilarated Cash. "A man with Glen's talents need never be behind bars again," he told a reporter. "I'm going to help him every way I can."

And for a while it worked. Sherley, a gaunt Oklahoman with palpable intensity, adapted to his place in the Johnny Cash world and seemed to confirm Cash's faith in the power of compassion. The former inmate became reacquainted with his son Bruce and daughter Ronda, re-married, and built a house and studio in the suburbs of Nashville. American news shows profiled him, talk show hosts interviewed him, and thousands cheered his live performances on the Cash shows. Where his mentor led, Sherley followed. But Sherley could only walk in the shadows for so long, recalled Cash's long-time manager Lou Robin. "He was a kingpin in the prison and garnered a lot of respect or fear, whatever it took to be that way. When he was on the outside he was always scrambling for the attention, a similar type of attention that he was getting in the prison. I think it really got to him after a while."

Sherley's prison drug habit crept back into his life. He'd cuss on Cash's shows, which in the early 1970s were unabashedly family-oriented. And he often showed up late for shows. And then the dark inclinations that had led him on many occasions to take his gun and rob a bank resurfaced. Marshall Grant saw it first when he tried to roust Sherley from bed so he'd make a flight to Cash's next gig. "You know what?" muttered Sherley, as he lit a cigarette, "I love you like a brother. But you know what I would really like to do to you? I would like to get a butcher knife, and I would like to start cutting you all to hell. I'd like to drain every drop of blood in your body out on that floor."

Sherley had to go. He was becoming the main character in Cash's "Cocaine Blues" who loves his transfusions and hates life and, in retrospect, a troubling prediction of Norman Mailer's awful experience with Jack Henry Abbott, an inmate the author had helped free in the early 1980s. Sherley retreated deeper into abuse, left his wife, and drifted until he finally landed at his brother's house near Salinas, California, some two-hundred miles southwest of Folsom State Prison. On May 11, 1978, seven years after his release from Folsom, Sherley walked out onto his brother's porch in the morning and shot himself in the head. His brother found him in the afternoon.

Sadly, Sherley's passing dealt the final blow to Cash's prison activism. By the late 1970s, he'd already seen political leaders fail to act, and even the prisons that had given him a hero's welcome grew hostile as the changing population demanded other styles of music. In time, his prison concerts ceased. "Well, I think he stopped going to prisons because it was just too much," explains Rosanne. "It was a burden. The physical weight alone of that much pain and trouble . . . and then making yourself accessible to it, and even thinking you could have the power to change some of it. Nobody can do that. I don't think it took too long before he realized that he wasn't the wizard that was going to fix all these people, and he started to withdraw." In the years after 1978, Cash rarely mentioned Sherley's name in public. It must have been painful to remember him. "There have been people that put some responsibility for dad's death on John," says Ronda Sherley. "You know, 'He could have done this' or 'He should have done that.' Or because he took an interest and brought Dad out of [prison], he should have been more responsible for him. I don't feel that way. I feel that John reached out his hand and was willing to help another person. And when Dad couldn't meet that expectation, it's not that John just threw him off to the side. He couldn't find a way to help him. And I don't know if anybody could have."

On January 13, 1968, Cash and June and Luther and Carl and Marshall and Fluke left Folsom State Prison under a warm winter's sun. The bleak clouds had dissipated, and Cash, dropping the worried-man countenance of the morning, smiled for Jim Marshall's camera. Marshall's photos capture a skip in Cash's step and an optimism about something, perhaps his future or the forthcoming album or his relationship with June (they'd be married in less than two months). Just how bright his world would become nobody could imagine. His recorded concert would transform his career, settle his personal life for a time, bring country music to international audiences, and enliven the prison reform debate.

Untold artists in the 1960s struck chords and strung together verse on behalf of the disenfranchised, but Cash literally met the outcasts of Folsom where they lived and made sure that the world saw his example. How much vanity seeped into this act of charity we will never know, but undeniable is At Folsom Prison's call to remember incarcerated people everywhere. As a plea to realize our humanity, the album recalls Dorothy Day's The Long Loneliness (1952) and King's Letter From A Birmingham Jail (1963). As a reminder of Johnny Cash's legacy, it is monumental.

Michael Streissguth 2008

Michael Streissguth is the author of Johnny Cash: The Biography (2006) and Johnny Cash At Folsom Prison: The Making Of A Masterpiece (2004).

Thanks to Leslie Bailey, Herm Card, Bestor Cram, and Wayne Stevens.

The show at Folsom in 1968 was a long one and I always thought that the songs that were not on the album were as worthy of being heard as the ones that were.

And memories … there are scenes as sharp in my memory as if it were last night! The look on Glen Sherley's face as I announced his song, the reaction from the cons when I introduced myself, and the faces. The pain and hopelessness of a soul beaten down; of failure, of failure to stay free of the system, of failure to be able to ignore today's pain.

But there are swelling balloons of joy to burst in a couple of hours for sure when they have to go back to their cells. But, for now, let it blow! We are in the timeless now. There is no calendar inside the cafeteria today, January 13, 1968.

I'm singing sweet hymns to them of mother, Jesus, freedom, children. But, of course the walls as well, and the joyous, most sacred, freedom of the spirit.

Dig in, join in, share in the joy with men who only had a couple of hours in months, maybe years time. There's some stuff here I'm proud of …

Johnny Cash

June, 1999

JOHNNY CASH AT FOLSOM PRISON was the first "country" record I ever listened to from beginning to end. My uncle, Arlon Earle, owned it and we were visiting him in Jacksonville, Texas. I first heard Hank Williams, Bob Wills, Jimmie Rodgers, and Ray Price, in that house — "hillbilly records" he called them, so I called them that, too. As I got older and discovered the Beatles and the Stones and Bob Dylan, only Johnny Cash survived the shift in my musical tastes. Cash was different.

He was a BADASS. He wore a lot of black and he sang about murder and dope and adultery and ghosts. He had genuine attitude. His music, more than anyone else's, was simultaneously COUNTRY and ROCK.

In 1968 John had his own television show and I NEVER, EVER missed it. I saw Neil Young, Linda Ronstadt and in his first network appearance, Bob Dylan. All during the most formative period in my musical life. Nothing else would influence as much as that hour a week until I met Townes Van Zandt in 1972.

I finally met John in 1987 at a photo session for a newspaper article publicizing a benefit we shared the bill on. Present were John, myself, Waylon Jennings and Mark Germino. It was John who noticed that everyone in the picture was wearing black except him.

In 1991 I dropped off the edge of the earth, resurfacing in '95 by way of the Davidson County Criminal Justice Center. Later that year Ry Cooder asked me to play electric guitar on John's contribution to the Dead Man Walking soundtrack. (I got to "be" Luther Perkins. How cool is that?) I hadn't seen John since I went away and when I walked into the green room at 16th Avenue Sound, he was standing over the pool table with his hand in an old fashioned picnic basket. He looked up when I entered the room and said "Steve — would you like a piece of tenderloin on a biscuit that June made this mornin'?" I allowed how I would and he said "I knew that you would." Then we went in and made a record — as if nothing bad had ever happened to either one of us.

Steve Earle

Troy NY, June 1999