|

|

|

| more images |

Sleeve Notes

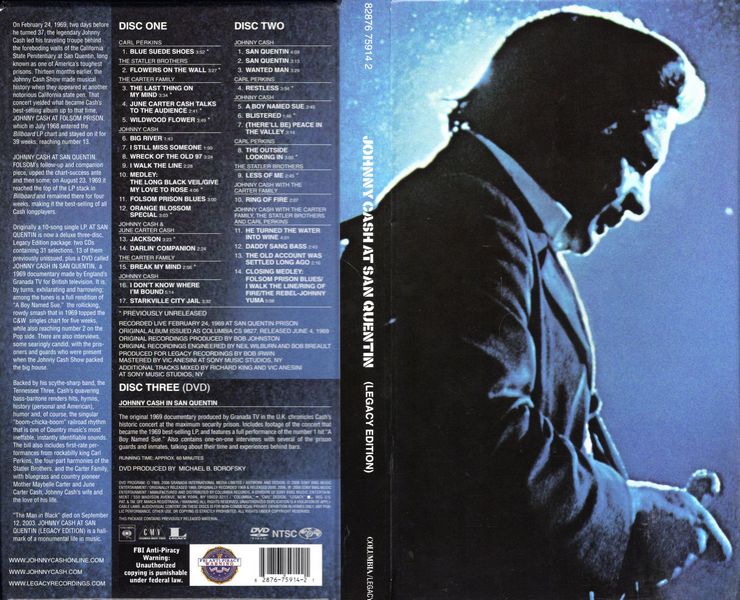

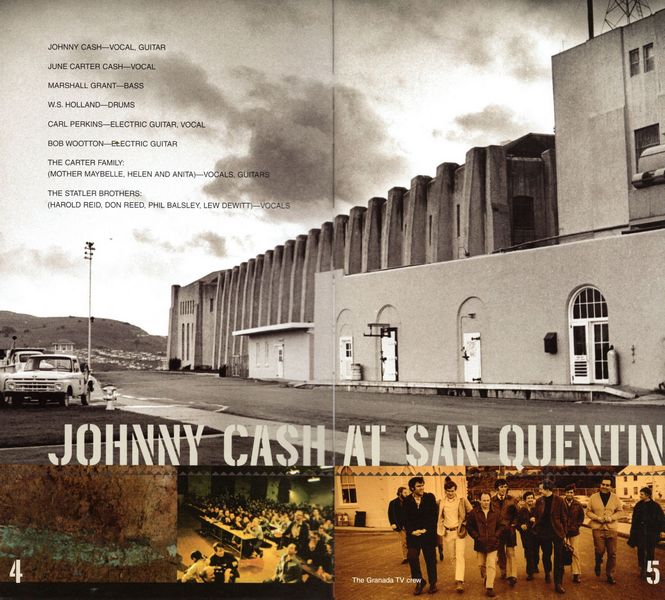

On February 24, 1969, two days before he turned 37, the legendary Johnny Cash led his traveling troupe behind the foreboding walls of the California State Penitentiary at San Quentin, long known as one of America's toughest prisons. Thirteen months earlier, the Johnny Cash Show made musical history when they appeared at another notorious California state pen. That concert yielded what became Cash's best-selling album up to that time. JOHNNY CASH AT FOLSOM PRISON, which in July 1968 entered the Billboard LP chart and stayed on it for 39 weeks, reaching number 13.

JOHNNY CASH AT SAN QUENTIN, FOLSOM'S follow-up and companion piece, upped the chart-success ante and then some; on August 23, 1969 it reached the top of the LP stack in Billboard and remained there for four weeks, making it the best-selling of all Cash longplayers.

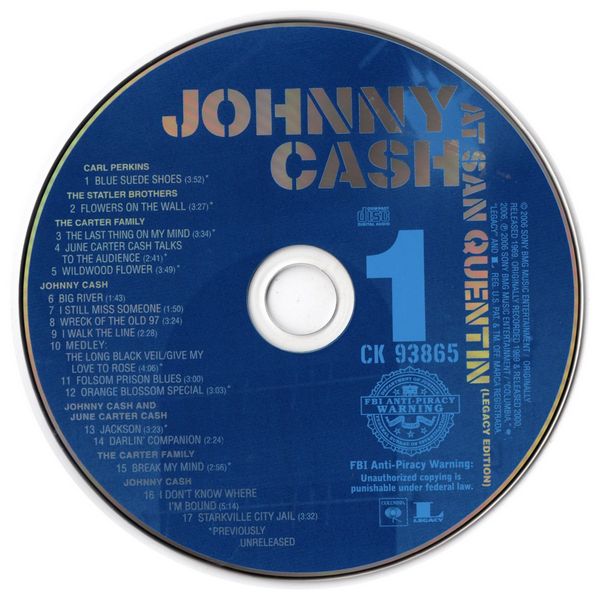

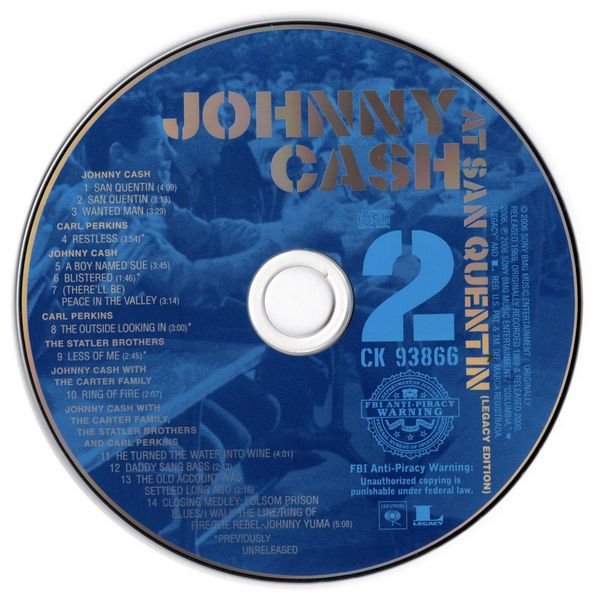

Originally a 10-song single LP. AT SAN QUENTIN is now a deluxe three-disc, Legacy Edition package: two CDs containing 31 selections, 13 of them previously unissued, plus a DVD called JOHNNY CASH IN SAN QUENTIN, a 1969 documentary made by England's Granada TV for British television. It is, by turns, exhilarating and harrowing; among the tunes is a full rendition of "A Boy Named Sue," the rollicking, rowdy smash that in 1969 topped the C&W singles chart for five weeks, while also reaching number 2 on the Pop side. There are also interviews, some searingly candid, with the prisoners and guards who were present when the Johnny Cash Show packed the big house.

Backed by his scythe-sharp band, the Tennessee Three, Cash's quavering bass-baritone renders hits, hymns, history (personal and American), humor and, of course, the singular "boom-chicka-boom" railroad rhythm that is one of Country music's most ineffable, instantly identifiable sounds. The bill also includes first-rate performances from rockabilly king Carl Perkins, the four-part harmonies of the Statler Brothers, and the Carter Family, with bluegrass and country pioneer Mother Maybelle Carter and June Carter Cash, Johnny Cash's wife and the love of his life.

"The Man in Black" died on September 12, 2003.

"You could feel the pressure," Johnny Cash told me some 30 years after the original release of the album you have in your hand. "A lot of tension, a lot of electricity. It was time for the show to start and everybody was looking for me and wondering when I'm coming out. And when I walked out there, it was total stillness, nobody said a word. I walked to the microphone and said, 'Hello, I'm Johnny Cash,' and then they reacted." He laughs. "Boy, did they react."

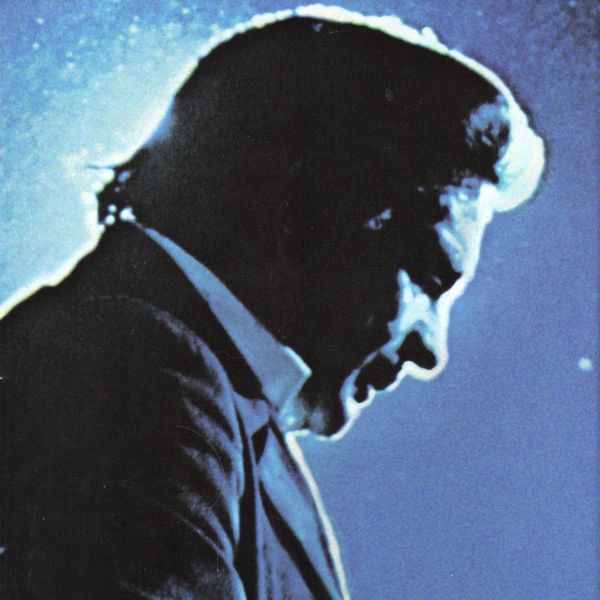

There's a photo of Johnny Cash that has now become iconic — you see it everywhere; teenagers wear it on T-shirts. In it Cash snarls like a punk rocker at the camera with his middle finger raised, flipping the bird. It was taken — by Jim Marshall — during the afternoon rehearsal for Cash's 1969 concert at San Quentin penitentiary. Some say it was aimed at a prison guard; Cash himself once said it was intended for a cameraman from the crew filming the concert for a British TV documentary who was getting between him and the audience. A captive audience, literally. The inmates of San Quentin — or those, at least, who weren't locked up on death row.

Whatever brought it on, nothing sums up the defiant, macho, outlaw Johnny Cash quite like that picture and the concert it was taken at. As Bob Johnston, At San Quentin's producer, recalls, "God, I've never seen anything like it. When Cash sang 'San Quentin, may you rot and burn in hell,' they were on the tables yelling. A lot of the guards were up on the runways with loaded guns, backing up the doors, and I'm backed up to the door with all of these guards with guns, and I'm thinking, 'Man! I should have brought Tammy Wynette and George Jones — anybody but Johnny Cash!'"

For all his talk of God and family, and there's been plenty of that, Johnny Cash was an excellent badass. If the last album he completed before he died in 2003 was a collection of his Mom's favorite hymns, the records that most defined his life — and certainly defined his mythic, Man In Black afterlife — were the pair of live albums he recorded back-to-back, in 1968 and '69, in two notorious California prisons, Folsom and San Quentin.

If the first concert, at Folsom, has become the better known — particularly now that Hollywood has chosen it as a metaphor for his life in Walk The Line — San Quentin might well be the better album. Like Johnston, who produced both albums, says — it's dangerous. Exultant too, thrilling in its edginess. And there's a humanity and an honesty you rarely hear on record — even more remarkable to see in the 1969 TV documentary on the accompanying DVD.

In the 13 months between the Folsom and San Quentin concerts, a lot had changed for Johnny Cash. He would find God, kick his amphetamine habit, and finally get June Carter to agree to marry him (doubtless something to do with finding God and kicking amphetamines). He also found himself with the biggest album of his career: the live At Folsom Prison album topped the country charts as well as crossed over to a rock audience that for a long time had little time for country music. Its success led to the offer of his own weekly prime time TV show. After a period when his life and career seemed headed for oblivion, Cash was at the top of his game.

But you didn't have to scratch too deep to find the hurt and anger and darkness. At San Quentin speaks with the rage of a prisoner, laughs with the gallows humor of a condemned man and sings with the intensity and conviction of someone who'd been through hell and lived to tell the tale. Tell it, not preach it. "There but for fortune" seemed as ingrained in Cash as his later godliness.

There was also a canniness and practicality to Cash. Ever since playing his first prison concert — and he'd played them pretty much since Sun Records released his second single, "Folsom Prison Blues" in 1956; prisoners heard it, he said, and "felt like I was one of them. They asked for me to play and the officials said it was alright so I showed up and played" — he was aware that the energy at these all-male performances was unlike that of his regular shows. "The very first one I ever played was Huntsville prison, Texas, and I realized right then that a prison show would be a perfect show for a live album. I just wanted to get that excitement on record because I thought it would really be an exciting thing to listen to."

As Cash moved from his twenties into his thirties and from the indie rock 'n' roll label Sun to major label Columbia's more conservative country music HQ in Nashville, that raw, masculine excitement had started to get away from him. But whenever he brought up the idea of recording a live album in prison — and he did, frequently, for a decade, he said — no-one listened. Meanwhile Cash and the Tennessee Two — Luther Perkins and Marshall Grant — continued with the prison concerts — including, in 1958, their first at San Quentin.

As real estate goes, it doesn't get much better than San Quentin — poised on a plot of land in exclusive Marin County, jutting out across the beautiful San Francisco Bay. But, like it says in the Johnny Cash song, California's oldest prison, and its only prison with a (still) operational gas chamber, is a "livin' hell." A place where men go not to play but to rot or die.

Merle Haggard was a San Quentin inmate in 1958 — sentenced to 15 years for a drunken, armed robbery attempt before he became a country singer — and he was at that concert, in the front row. His recollections could just as well describe the concert held in that same high-ceilinged mess hall ten years later and recorded for posterity.

"What stood out about Johnny Cash when I saw him at San Quentin, more even than his music, was his demeanor. He was a bit cocky and a bit arrogant — his voice was shot because he'd been up too long the night before. He was supposed to be there to sing songs, but it seemed like it didn't matter whether he was able to sing or not. He was just mesmerizing. There was just this excitement. It didn't even matter that he was free, because there was a connection there, an identification. This was somebody who was singing a song about your personal life. Even the people there who weren't fans of Johnny Cash — it was a mixture of people, all races — were by the end of that show."

The sense of connection and identification with outlaws and underdogs seemed innate to Cash. As the sensitive and less-than-favored son of an abusive father, his radar was well-tuned to injustice, while the poverty of his childhood years, his brother's death at the sawmill, and what appears to be a genetic tendency toward alcoholism fuelled his renegade tendencies. From the end of the '50s until the first prison album At Folsom, Cash was jailed seven times — albeit on an overnight basis — for trashing various cars, starting a forest fire, redecorating hotels, smuggling drugs over the Mexican border, and general conduct unbecoming to a Grand Ole Opry performer (until he kicked out the footlights after one performance, after which the Opry kicked him out).

Of his substance abuse, he wrote in his autobiography, he was 11 when he 'clearly remembered] the first mood-altering drug to enter my body" (given to him in hospital after he broke a rib). He thought, "Boy, this is really something. I'll have to have some more of that sometime." Fourteen years later, touring with Ferlin Husky and Faron Young, he did — amphetamines this time, which "increased my energy, sharpened my wit, banished my shyness, improved my timing, turned me on like electricity flowing into a light bulb." Cash learned to wash them down with alcohol to take off the edge and throw in barbiturates to add valleys to the peaks.

By the mid '60s he was taking "up to 100 pills a day," scrawny from speed, his voice sometimes shot. "I don't know what it was," he told me. "It was just something burning inside of me that I couldn't quench." Several people tried to help, including June Carter, the woman he'd loved since he first heard her on the radio, as a child, and who had been in his touring band since 1963 (along with her mother, the country legend Maybelle Carter, and her sisters Anita and Helen, plus gospel quartet the Statler Brothers, The Tennessee Two — Marshall and Luther — had since been expanded to Three with the addition of drummer W.S. Holland as well as rock 'n' roller and former Sun label mate Carl Perkins).

In 1966 Cash's first wife Vivian had enough of his behavior and divorced him. Cash simply moved in with his buddy Waylon Jennings and the drug intake expanded. To the point where even Cash couldn't take it anymore. In 1967 he crawled into Nickajack Cave on the Tennessee River, intending to die, but June found him, persuaded him that God had other plans for him, and led him back home to begin what Cash called "her lifelong dedication to cleaning me up." Cash accepted God and resolved to throw away his pills. But first he recorded At Folsom Prison.

He had never forgotten his desire to make a live prison album. "I just waited," he said, "until I had the right producer who saw a way to do it." That man was Bob Johnston, producer of Columbia greats like Bob Dylan, Simon & Garfunkel and Leonard Cohen. He had moved to Nashville to take over Columbia's country music division. As he recalls, "Johnny walked in the back door one day with some black guy who was the cleanup guy, and he sat down at my desk and said, 'Well, I've always wanted to record an album at a prison and nobody would let me for eight years, and I don't guess you will either.' I said, 'Yeah?' And I picked up the phone" and called Folsom and San Quentin.

The reason the Folsom album was made first is because the Folsom warden answered first, simple as that. "I got the warden, Duffy, and I handed Johnny the telephone and left."

The concert, in January 1968, and the recording, done with a mobile recording truck, turned out to be everything Cash had hoped for. Johnston aside, his record label was less than enthusiastic. Johnston recalls a phone call from the head of Columbia, Clive Davis, saying "that if I took Cash to a prison it would ruin his career and I wouldn't be with CBS anymore." As it turned out, sales of the album were phenomenal.

"So then," says Johnston, "I took him to San Quentin."

On February 24th, 1969 — two days short of his 37th birthday — Cash drove up for the fourth time to San Quentin's forbidding steel gates, drove down the driveway, the watchtower guard's gun trained on the car, up to the grim, concrete building where they would play. June, his wife of nine months, sat close beside him. Also there was the same troupe he'd taken to Folsom Prison — bar Luther Perkins, Cash's longtime guitar player, who had died in September '68 during a fire in his home, the only dark cloud on an otherwise brilliant year. Replacing him was Bob Wooton, a young man who'd approached Cash at a concert and stunned him with his ability to reproduce Luther's parts note for note.

The only other change was that this time, unlike at Folsom Prison, Cash was not on drugs. "I think it might have been the first [drug-free performance]," he said. Despite the lack of chemical crutch, there were no nerves, "I'd been to San Quentin many times and felt pretty well at home."

God may have saved Cash, but there was no preaching at San Quentin. The second prison album is, if anything, even more uncompromising than the first. On one of his previous visits to San Quentin, as he strode grim-faced through the corridor, a prisoner had called out asking him how he liked the place. Cash's reply was, "It's a hell-hole." June suggested he write a song saying how he felt. He debuted it — then sang it a second time with even more feeling immediately afterwards at the prisoners' request. You can only imagine how they would have felt hearing those words for the very first time.

Says Johnston — who was taping the show from 30 feet up in the balcony, where the guards were pacing about with guns — "There was very nearly a riot." If Cash had said the word — and you can see from the documentary that he was tempted — there might well have been one. But Cash defused the situation by asking, with a laugh, "If any of the guards are still speaking to me could I have a glass of water?" There's booing as one of them brings it over. He followed the song with a new outlaw ballad — written, he tells the audience, with Bob Dylan, "the greatest writer of our time," though a better reception is given the first-ever airing of Shel Silverstein's song, "A Boy Named Sue." Released as a single, it would become a big crossover hit, knocking the Rolling Stones off the top of the U.S. charts.

There are spiritual songs in the concert too, like "(There'll Be) Peace In The Valley," sentimental family songs, with the Carter women, dressed like angels in white, cooing harmonies, and sentimental family songs like "Daddy Sang Bass," but the biggest cheers are for when Cash cusses, tells a story about getting busted for picking flowers in Mississippi and warns an English cameramen, who's just dropped a piece of equipment, that bending over in a prison is not a great idea.

None of those last bits made it onto the ten-song original (21 tracks short of this version, which features the entire concert including warm-up numbers by the Statlers, Carters and Perkins). Nevertheless, released in the Woodstock summer of '69, the raw, ballsy At San Quentin — you can smell the testosterone — hit the number one spot even more swiftly than its predecessor and stayed there for four weeks. And even more than At Folsom Prison, its stark, no-frills sound and authentic, been-there lyrics made inroads into the rock market, leading Cash on a path that would eventually lead to his association with the famed producer Rick Rubin — a big fan of both prison albums — and even to being hailed as the Godfather of Gangsta Rap.

As Bono of U2 wrote in his liner notes to a later Johnny Cash compilation, God, "Johnny Cash doesn't sing to the damned, he sings with the damned. Sometimes you feel he might prefer their company."

— Sylvie Simmons

I bought a copy of JOHNNY CASH AT SAN QUENTIN the day it was originally released. Since then, I've owned it in every format from eight-track to compact disc. It's been a source of strength and inspiration for me throughout every nuance of my life. I seldom take a trip without it.

While on tour with the Cash show as a band member in Hobert, Tasmania, I met an audio/video pirate who alluded to the fact that for the right amount of money he could get me a bootlegged copy of the video that the BBC had filmed the night of Cash's San Quentin concert. As an added bonus, he said he'd throw in a tape of the songs that had been deleted from the commercial recording.

Like a naive fool, I gave him my money then sat up most of the night waiting for him to bring me the tapes. His word was as hollow as a politician's promise. He never returned. I finally gave up, went to bed, and forgot about it...until now. After twenty years, I welcome the re-release of this classic recording, complete with its lost chapters. Locked away in a vault for so long, it showcases Cash at his zenith — a master communicator, interpreter and missionary, who sang songs for the souls locked away, inside one of hell's most famous waiting rooms.

This February 24th, 1969 concert marks the fourth time that Cash appeared at San Quentin. The first time was on January 1, 1958. He and his band played in the middle of the prison yard. It was a rain-soaked performance which they endured until guitarist Luther Perkins' amplifier finally drowned out. Cash's songs, coupled with his commitment to entertain the inmates in spite of the elements, won him their approval and solid acceptance as being "one of them." Subsequently, he has been asked to come back and perform repeatedly.

Possibly the most famous inmate to witness a Cash performance at San Quentin was Merle Haggard. Haggard's days of being incarcerated there have been widely publicized. He was eventually granted a full pardon by then-governor Ronald Reagan. Haggard, like Cash, has used his life as a canvas for helping the bleeding-heart underdog. He has given the downtrodden a broader voice and repeatedly shined as a light on their behalf. It seemed fitting here, to ask him to represent the men of San Quentin.

He speaks with the confidence of a free man, though his voice is tinged with a wariness for the shadows that only feebly conceal the images of the way it used to be.

Marty Stuart

Nashville, Tennessee

2/20/2000

Marty Stuart interviews Merle Haggard

MS: When was the first time you saw Johnny Cash perform at San Quentin?

MH: New Year's Day 1958. It was an annual occurrence that took place that the authorities put on for us as kind of a variety show. It included everything from strippers to local country music talent out of Frisco. They brought in magicians, jugglers and, in this case, Johnny Cash.

MS: What was your impression of him?

MH: I was mesmerized by him — even though he didn't have his voice. He had been over in Frisco the night before, roaring, and he'd lost his voice. He could barely whisper his songs, but he was able to capture the imagination of these men who were not necessarily country music fans. I really wasn't a big Johnny Cash fan because I hadn't been introduced to much of his music yet. But that soon changed.

MS: During his performance, what most touched your heart? What did you carry back into your cell with you?

MH: Even without his voice, he had a leadership ability that was powerful from the moment he took the stage. I knew I could do whatever he was doing. I knew something like that was within the reach of my limits of talent. I felt like I could do what he was doing, and I saw how powerful it was. To tell the truth, it may have been the first ray of daylight I had seen in my entire life.

MS: Take me inside the collective mind of the prisoners. What did the word of Johnny Cash coming mean to them?

MH: Well, there again, nobody except me and about fifteen guys cared for the fact that he was coming, because country music was at an all-time low. Most everybody listened to rock 'n' roll, blues, jazz, whatever...so I expected the strippers to run away with the show. When Johnny Cash didn't even show up with a voice, I thought, "how's he going to pull this off?" I don't know how he did it, but he did. He captured the entire prison. I don't think there was a guy in the entire joint who didn't like Johnny Cash when that show was over.

MS: When the show was over and reality set in, what did Cash's performance leave behind in terms of morale?

MH: His presence didn't leave when the show was over. It continued to hang around, mainly inside of me. But it gave everybody the feeling that if they could learn to play "Folsom Prison Blues," maybe they could stay out of prison.

MS: During the course of the evening of his 1969 performance, Cash entertained the inmates with some of his hits, protest songs, novelty songs and traditional folk songs. He also sang four inspirational songs, which offered the listeners the promise of redemption and the assurance of an eternal peace. These songs seemed to echo hope into a seemingly hopeless environment.

MH: Well, he offered the beliefs that you and I were raised on. He brought Jesus Christ into the picture, and he introduced Him in a way that the tough, hardened, hard-core convict wasn't embarrassed to listen to. He didn't point no fingers; he knew just how to do it.

MS: Do you think if that same concert staged in 1969 was held today, it would have the same impact as it did then?

MH: You bet I believe so. That someone who was given a name above all is still in charge. It's easy to feel the spiritual connection when you listen to this event. Cash had God's touch all over him. People latched onto him. I'd say 95% of those prisoners that were there that day have never forgotten Johnny Cash.

During the show at San Quentin in 1969, it seemed that everybody that worked for Granada TV was on stage in front of me. At some point, I walked around my microphone and yelled, "Clear the stage! I can't see my audience!" Nobody moved. So I gave them "the bird." Hence that picture.

Fast forward to 1999. I was lying in intensive care when I felt a presence in the room. I opened my eyes and there stood Merle Haggard silently studying me. He bent down, put his hand behind my head, rubbed his forehead against mine and said, "you're gonna be alright, Cash." And I am. Thanks for the return visit, Hag.

Johnny Cash

March, 2000

Where you go, I will go. Whatever you do, I will do, and your people shall be my people. And so it was that day in San Quentin Prison.

We had come to see the lost and the lonely ones. I had married this man, Johnny Cash, and there was something in him that drew him to these men. He had been in their shoes, at least some of them. He had hollered louder than any of them, when he was picked up and jailed for disturbing the peace, not just once but seven times. All of that was a long time before we were married and this was a day not like any other will be again.

I could feel the electricity in his hands and I held on for dear life. "Sing 'Folsom Prison Blues,' John," someone called from the blackness behind a window as we passed by the lockdown for those who waited to die. I hung close to Mother Maybelle and my sisters, Helen and Anita. We seemed to be one, the four of us. I was afraid. Another prisoner called, "What is John really like, June?" It was like a revelation. "He's tall, he's lean and he's mean. There's just not another one like him." I'm still searching deeper into the soul of this man for the light that shines somewhere within him. It is the light that only the faithful know.

"How do you like San Quentin, Cash?" a young man called from the front of the Grey Stone Chapel. "San Quentin is a hell-hole," John whispered to me. "It ought to rot and burn in hell for all the good it does." "So write it," I said. Surely we're here for some reason. There ought to be some way for redemption for these men.

I'd never felt such a burden on my husband's heart, and I'd certainly never felt such a burden on mine. I held tighter to his hand and I was still afraid. I remember praying: "Lord, God, help us all and show us the way."

If you're a woman visiting a prison, you have crazy ideas. You look at all the men and your effect on one prison guard. "Mr. Cash, don't you dare look at these men in the eyes. I'd suggest you and your family look just over their heads at the wall in the back of the room." I had always looked my audience in the eye, and this one guard tells me I can't. San Quentin is a maximum security prison. Some men are here for armed robbery, rape, pedophilia, arson, murder. And there were a few innocent men. It felt like a dream. "Oh Lord," I cried. For I could still see all the men jumping on my bones, and my sisters' bones, too. They were beautiful girls.

"Sing 'Give My Love To Rose, Please Won't You, Mister.'" "Hey Cash!" "Great day, Cash!" "You as big as a mountain, that's what you is, man, that's for sure." This holler came from a big brown-skinned man who weighed about 300 pounds. He clenched a small accordion in his spindly arms, and was cavortin' to and fro, on his way throughout the crowd, singing at the top of his voice. "Give my love to Rose, please won't you, mister?" And if you looked into his eyes, you could see a dream there. A dream that made that black-eyed Cajun man one of the famous "Tennessee Two." I could see his eyes, all fierce, violently intense, pugnacious and spirited. This man wanted something real bad. He dragged it across the room, now almost in a whisper. Boom chick-a-boom, boom chick-a-boom. Then I woke up to what was really happening; it was a dream and it was.

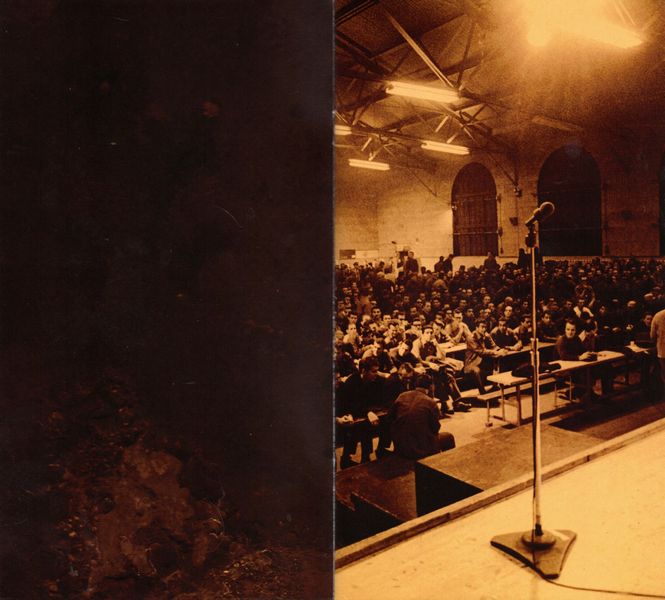

"Men, you've waited long enough!" It was about time I let go of John's hand and he walked away. He slung his guitar across his back, slithered like a snake onto that stage and said, "Hello, I'm Johnny Cash." I don't know if explode is the word or not. Some kind of internal energy for those men, the prisoners, the guards, even the warden, gave way to anger, to love and to laughter. It all came together. A reaction like I'd never seen before. I was enraged inside, a feeling of fire, dangerously tense. And John sung quietly, "San Quentin, you're livin' hell to me."

You use your imagination, we're all in a state of wickedness, we're condemned sinners. "Sing it, Cash! You know it man, we're all in hell here!" "So you give us the word, Cash, and we'll beat the hell out of them, just for the hell of it."

It took seven, maybe ten minutes before he got to repeat the first and second line of his first-time ever heard-of song, "San Quentin."

"San Quentin, you've been livin' hell to me. You've galded me since 1963." This sore made by chafing it in the most humiliating place, you add bitterness and bile. You find yourself walking, trying to strut and swagger. But about all that you can do is spread your legs and swagger.

"I've seen them come and go and I've seen them die."

A basic word, meaning to breathe your last breath, to wither away and that's it, you're dead, that's all. That's all, you perish, you're gone.

"So, long ago, I stopped asking why."

"San Quentin, what good do you think you do? You've cut and scarred me through and through. You bend my heart and mind and you warp my soul. Your stone walls turn my blood a little cold."

So, there, that is a little of how we all were that day. We were all cut and scarred, warped and bent. But, still, we faced the San Quentin crowd. We were strong because John was strong.

I remember Mother Maybelle, the Statler Brothers, Helen and Anita, my sisters, Carl Perkins. But most of all I could see the prison guards, walking slow with machine guns, just over our heads, suspended by a wire cat walk. We sung behind John about "Peace In The Valley."

John held these men in suspense, they were mesmerized, hypnotized and spellbound and so were we. "San Quentin" was their song and Johnny Cash was theirs, and they decided not to riot that day. He held them by a thread, and we were saved by that thread. He sang "San Quentin" one more time, and we claimed it, same as he.

June Carter Cash

March, 2000

It was in the early winter of 1968 that Johnny asked me to set up a concert for him at San Quentin State Prison outside of San Francisco. This was my first experience at such an unusual event. John, June, the Statler Brothers, Carl Perkins and the Carter Family, the band and I all entered the prison at the same time about an hour before show time on the night of February 24, 1969.

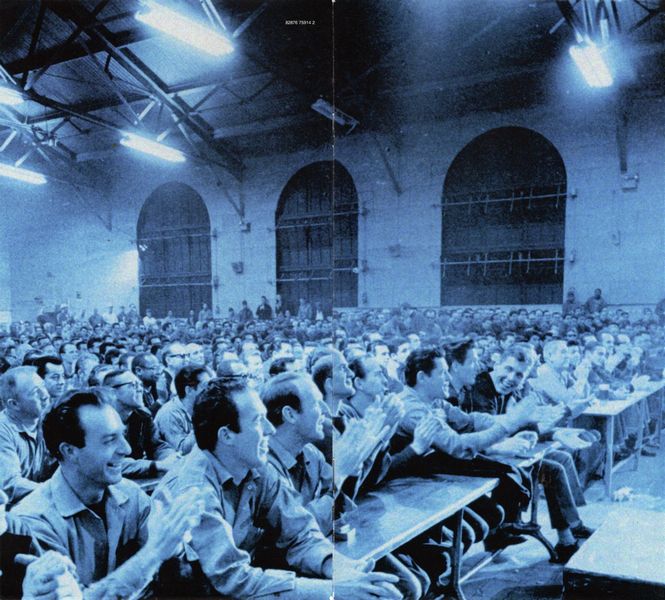

It was a lonely feeling as we walked deeper into the prison and heard the steel doors slam behind us one after the other. We walked about ten minutes to the mess hall where the show would take place. Granada Television from England and Columbia Records were there with all their gear to memorialize the occasion, so as never to be forgotten.

There were probably 1,000 inmates jammed into the hall. The show proceeded and the response was deafening, especially for the protest songs; "San Quentin, may you rot and burn in hell." Encores only helped to raise the event to a fever pitch. It was fascinating to study the intensity in the faces of the men while they escaped from reality for a few hours. I asked the Chief of Security if we didn't need more guards to protect the stage area. He pointed out that if he were to use 100 guards that night and the situation got out of control, those one hundred guards or even another hundred wouldn't be able to do much. Not very reassuring for me, but he said that most of the prisoners didn't want any problems and not to worry. Small solace!

Interestingly, as I had read before about prison life, the most powerful inmates sat in the front row in their tailored uniforms with their "assistants" coming over to light their cigarettes and bring them drinks.

My final recollection is that during the show when I walked around the mess hall to check the vocal sound, I stopped near the back wall and for some reason, I looked up. There, about five feet over my head was a fork with food still on it stuck in the wall. Who knows how long it had been there. It kind of summed up the feelings of those inmates who no doubt wanted to be anywhere other than where they were that night, at least until Johnny Cash got there.

Lou Robin

Westlake Village, CA January, 2000

The Legacy Edition represents the performance of the Johnny Cash Show Review as it unfold-ed on February 24,1969 at San Quentin Prison. The incredible evening was originally captured on one-inch, eight-track tape by recording engineers Neil Wilburn and Bob Breault, manning Columbia Records' West Coast mobile recording unit. This new set showcases this historic event accurately and chronologically; the complete set of vintage masters has been painstakingly archived and reassembled in original running order. Therefore — with the exception of a few songs that fell victim to tape run-outs that evening — this edition now presents the show in its most complete form possible.

The makeshift stage at San Quentin was a busy place that evening, with performers entering and exiting throughout different segments of the nearly three-hour event; Johnny and his friends Carl Perkins, the Statler Brothers and the Carter Family would be showcased individually, then uniquely reconfigured for group performances. Ultimately, the evening consisted of a captivating blend of signature songs from each artist, material that was featured on each artist's recent or upcoming release, along with songs that had never been performed — or even rehearsed — until that very day. The easy, sometimes bordering-on-rowdy stage banter between the artists — and with the San Quentin audience — lends nearly as much to the show as the performances themselves, offering an insightful, deeply personal glimpse into a most unique evening in a most unique setting.

Bob Irwin

Legacy Edition producer