|

|

Sleeve Notes

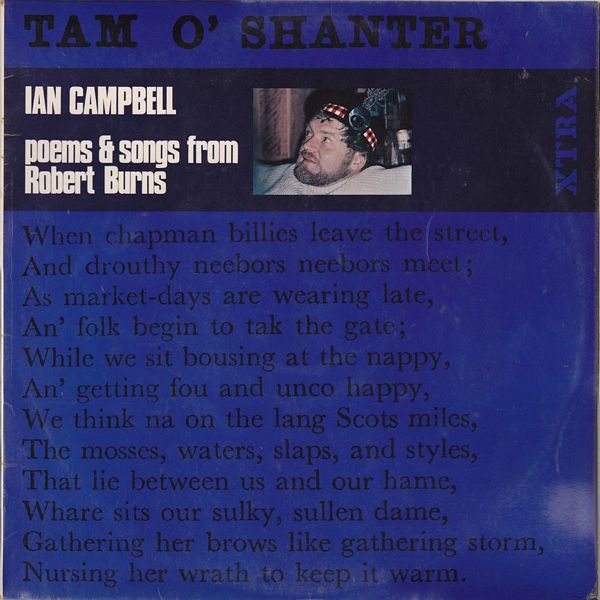

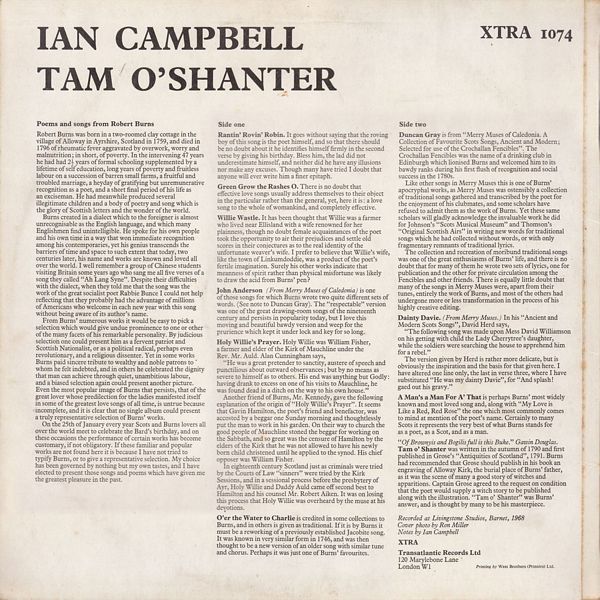

Robert Burns was born in a two-roomed clay cottage in the village of Alloway in Ayrshire, Scotland in 1759, and died in 1796 of rheumatic fever aggravated by overwork, worry and malnutrition; in short, of poverty. In the intervening 47 years he had had 2 years of formal schooling supplemented by a lifetime of self education, long years of poverty and fruitless labour on a succession of barren small farms, a fruitful and troubled marriage, a heyday of gratifying but unremunerative recognition as a poet, and a short final period of his life as an exciseman. He had meanwhile produced several illegitimate children and a body of poetry and song which is the glory of Scottish letters and the wonder of the world.

Burns created in a dialect which to the foreigner is almost unrecognisable as the English language, and which many Englishmen find unintelligible. He spoke for his own people and his own time in a way that won immediate recognition among his contemporaries, yet his genius transcends the barriers of time and space to such extent that today, two centuries later, his name and works are known and loved all over the world. I well remember a group of Chinese students visiting Britain some years ago who sang me all five verses of a song they called Ah Lang Syne. Despite their difficulties with the dialect, when they told me that the song was the work of the great socialist poet Rabbie Bunce I could not help reflecting that they probably had the advantage of millions of Americans who welcome in each new year with this song without being aware of its authors name.

From Burns numerous works it would be easy to pick a selection which would give undue prominence to one or other of the many facets of his remarkable personality. By judicious selection one could present him as a fervent patriot and Scottish Nationalist, or as a political radical, perhaps even revolutionary, and a religious dissenter. Yet in some works Burns paid sincere tribute to wealthy and noble patrons to whom he felt indebted, and in others he celebrated the dignity that man can achieve through quiet, unambitious labour, and a biased selection again could present another picture. Even the most popular image of Burns that persists, that of the great lover whose predilection for the ladies manifested itself in some of the greatest love songs of all time, is untrue because incomplete, and it is clear that no single album could present a truly representative selection of Burns works.

On the 25th of January every year Scots and Burns lovers all over the world meet to celebrate the Bards birthday, and on these occasions the performance of certain works has become customary, if not obligatory. If these familiar and popular works arc not found here it is because 1 have not tried to typify Burns, or to give a representative selection. My choice has been governed by nothing but my own tastes, and I have elected to present those songs and poems which have given me the greatest pleasure in the past.

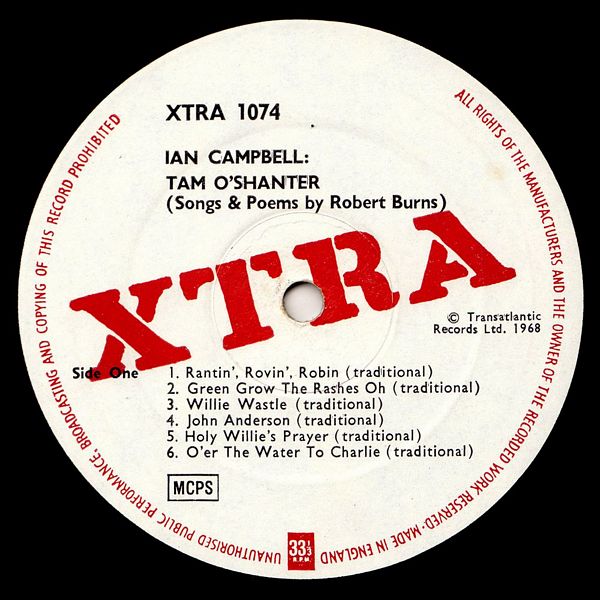

Rantin Rovin Robin. It goes without saying that the roving boy of this song is the poet himself, and so that there should be no doubt about it he identifies himself firmly in the second verse by giving his birthday. Bless him, the lad did not underestimate himself, and neither did he have any illusions nor make any excuses. Though many have tried I doubt that anyone will ever write him a finer epitaph.

Green Grow the Rashes O. There is no doubt that effective love songs usually address themselves to their object in the particular rather than the general, yet, here it is: a love song to the whole of womankind, and completely effective.

Willie Wastle. It has been thought that Willie was a farmer who lived near Ellisland with a wife renowned for her plainness, though no doubt female acquaintances of the poet took the opportunity to air their prejudices and settle old scores in their conjectures as to the real identity of the unfortunate weavers wife. I prefer to believe that Willies wife, like the town of Linkumdoddie, was a product of the poets fertile imagination. Surely his other works indicate that meanness of spirit rather than physical misfortune was likely to draw the acid from Burns pen?

John Anderson (From Merry Muses of Caledonia) is one of those songs for which Burns wrote two quite different sets of words. (See note to Duncan Gray). The respectable version was one of the great drawing-room songs of the nineteenth century and persists in popularity today, but I love this moving and beautiful bawdy version and weep for the prurience which kept it under lock and key for so long.

Holy Willies Prayer. Holy Willie was William Fisher, a farmer and elder of the Kirk of Mauchline under the Rev. Mr. Auld. Alan Cunningham says, He was a great pretender to sanctity, austere of speech and punctilious about outward observances; but by no means as severe to himself as to others. His end was anything but Godly: having drank to excess on one of his visits to Mauchline, he-was found dead in a ditch on the way to his own house.

Another friend of Burns, Mr. Kennedy, gave the following explanation of the origin of Holy Willies Prayer. It seems that Gavin Hamilton, the poets friend and benefactor, was accosted by a beggar one Sunday morning and thoughtlessly put the man to work in his garden. On their way to church the good people of Mauchline stoned the beggar for working on the Sabbath, and so great was the censure of Hamilton by the elders of the Kirk that he was not allowed to have his newly born child christened until he applied to the synod. His chief opposer was William Fisher. In eighteenth century Scotland just as criminals were tried by the Courts of Law sinners were tried by the Kirk Sessions, and in a sessional process before the presbytery of Ayr, Holy Willie and Daddy Auld came off second best to Hamilton and his counsel Mr. Robert Aiken. It was on losing this process that Holy Willie was overheard by the muse at his devotions.

Oer the Water to Charlie is credited in some collections to Burns, and in others is given as traditional. If it is by Burns it must be a reworking of a previously established Jacobite song. It was known in very similar form in 1746, and was then thought to be a new version of an older song with similar tune and chorus. Perhaps it was just one of Burns favourites.

Duncan Gray is from Merry Muses of Caledonia. A Collection of Favourite Scots Songs, Ancient and Modern; Selected for use of the Crochallan Fencibles. The Crochallan Fencibles was the name of a drinking club in Edinburgh which lionised Burns and welcomed him to its bawdy ranks during his first flush of recognition and social success in the 1780s.

Like other songs in Merry Muses this is one of Burns apocryphal works, as Merry Muses was ostensibly a collection of traditional songs gathered and transcribed by the poet for the enjoyment of his clubmates, and some scholars have refused to admit them as the work of Burns. Yet these same scholars will gladly acknowledge the invaluable work he did for Johnsons Scots Musical Museum and Thomsons Original Scottish Airs in writing new words for traditional songs which he had collected without words, or with only fragmentary remnants of traditional lyrics.

The collection and recreation of moribund traditional songs was one of the great enthusiasms of Burns life, and there is no doubt that for many of them he wrote two sets of lyrics, one for publication and the other for private circulation among the Fencibles and other friends. There is equally little doubt that many of the songs in Merry Muses were, apart from their tunes, entirely the work of Burns, and most of the others had undergone more or less transformation in the process of his highly creative editing.

Dainty Davie. (From Merrv Muses.) In his Ancient and Modern Scots Songs, David Herd says, The following song was made upon Mess David Williamson on his getting with child the Lady Cherrytrees daughter, while the soldiers were searching the house to apprehend him for a rebel. The version given by Herd is rather more delicate, but is obviously the inspiration and the basis for that given here. I have altered one line only, the last in verse three, where I have substituted He was my dainty Davie, for And splash! gaed out his gravy.

A Mans a Alan For A That is perhaps Burns most widely known and most loved song and, along with My Love is Like a Red, Red Rose the one which most commonly comes to mind at mention of the poets name. Certainly to many Scots it represents the very best of what Burns stands for as a poet, as a Scot, and as a man. Of Brownyis and Bogilis full is this Buke. Gawin Douglas.

Tam o Shanter was written in the autumn of 1790 and first published in Groses Antiquities of Scotland, 1791. Burns had recommended that Grose should publish in his book an engraving of Alloway Kirk, the burial place of Burns father, as it was the scene of many a good story of witches and apparitions. Captain Grose agreed to the request on condition that the poet would supply a witch story to be published along with the illustration. Tam o Shanter was Burns answer, and is thought by many to be his masterpiece.