|

|

Sleeve Notes

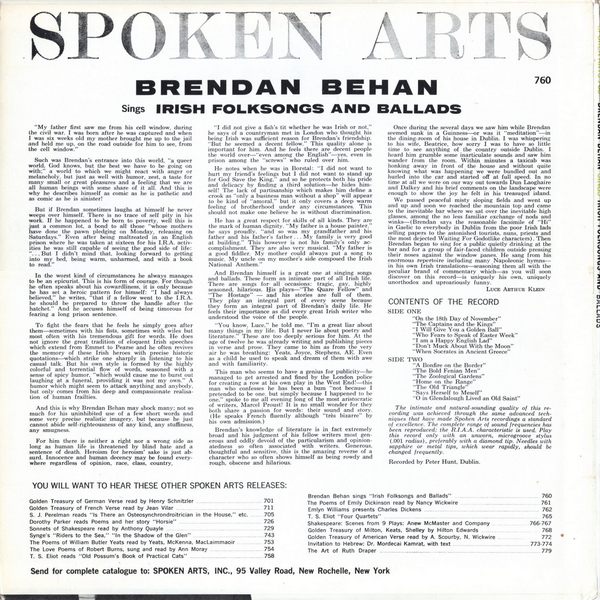

"My father first saw me from his cell window, during the civil war. I was born after he was captured and when I was six weeks old my mother brought me up to the jail and held me up, on the road outside for him to see, from the cell window."

Such was Brendan's entrance into this world, "a queer world, God knows, but the best we have to be going on with;" a world to which we might react with anger or melancholy, but just as well with humor, zest, a taste for many small or great pleasures and a feeling that we are all human beings with some share of it all. And this why he describes himself as comic as he is pathetic and as comic as he is sinister!

But if Brendan sometimes laughs at himself he never weeps over himself. There is no trace of self pity in his work. If he happened to be born to poverty, well this just a common lot, a bond to all those "whose mothers have done the pawn pledging on Monday, releasing on Saturdays." Even after being maltreated in an English prison where he was taken at sixteen for his I.R.A. activities he was still capable of seeing the good side of life: "… But I didn't mind that, looking forward to getting into my bed, being warm, unharmed, and with a book to read."

In the worst kind of circumstances he always manages to be an epicurist. This his form of courage. For though he often speaks about his cowardliness, it is only because he has set a heroic pattern for himself: "I had always believed," he writes, "that if a fellow went to the I.R.A. he should be prepared to throw the handle after the hatchet." And he accuses himself of being timorous for fearing a long prison sentence.

To fight the fears that he feels he simply goes after them—sometimes with his fists, sometimes with wiles but most often with his tremendous gift for words. He does not ignore the great tradition of eloquent Irish speeches which extend from Emmet to Pearse and he often revives the memory of these Irish heroes with precise historic quotations—which strike one sharply in listening to his casual talk. But his own style is formed by the highly colorful and torrential flow of words, seasoned with a sense of spicy humor, "which would cause me to burst out laughing at a funeral, providing it was not my own." A humor which might seem to attack anything and anybody, but only comes from his deep and compassionate realisation of human frailties.

And this why Brendan Behan may shock many; not so much for his uninhibited use of a few short words and some very precise realistic imagery, but because he just cannot abide self- righteousness of any kind, any stuffiness, any smugness.

For him there is neither a right nor a wrong side as long as human life is threatened by blind hate and a sentence of death. Heroism for heroism* sake is just absurd. Innocence and human decency may be found everywhere regardless of opinion, race, class, country.

"I did not give a fish's tit whether he was Irish or not," he says of a countryman met in London who thought his being Irish was sufficient reason for Brendan's friendship. "But he seemed a decent fellow." This quality alone is important for him. And he feels there are decent people the world over—"even among the English"—yes, even in prison among the "screws" who ruled over him.

He notes when he was in Borstal: "I did not want to hurt my friend's feelings but I did not want to stand up for God Save the King," and so he protects both his pride and delicacy by finding a third solution—he hides himself! The lack of partisanship which makes him define a crook as "only a business man without a shop" will appear to be kind of "amoral" but it only covers a deep warm feeling of brotherhood under any circumstances. This should not make one believe he is without discrimination.

He has a great respect for skills of all kinds. They are the mark of human dignity. "My father is a house painter," he says proudly, 'and so was my grandfather her and his father and his father's father… My family is very good at building." This however is not his family's only accomplishment. They are also very musical. "My father is a good fiddler. My mother could always put a song to music. My uncle on my mother's side composed the Irish National Anthem".

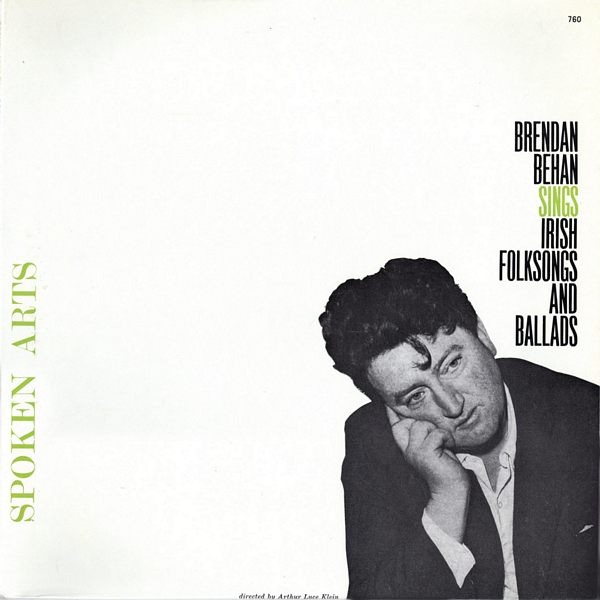

And Brendan himself is a great one at singing songs and ballads. These form an intimate part of all Irish life. There are songs for all occasions, tragic, gay, highly seasoned, hilarious. His plays—"The Quare Fellow" and "The Hostage"—and his stories are full of them. They play an integral part of every scene because they form an integral part of Brendan's daily life He feels their importance as did every great Irish writer who understood the voice of the people.

"You know, Luce," he told me. "I'm a great liar about many things in my life. But I never lie about poetry and literature." These are too deeply serious for him. At the age of twelve he was already writing and publishing pieces in verse and prose. They came to him as from the very air he was breathing: Yeats, Joyce, Stephens, AE. Even as a child he used to speak and dream of them with awe and with familiarity.

This man who seems to have a genius for publicity—he managed to get arrested and fined by the London police for creating a row at his own play in the West End!—this man who confesses he has been a bum "not because I pretended to be one, but simply because I happened to be one," spoke to me all evening long of the most aristocratic of writers, Marcel Proust! It is no small wonder for they both share a passion for words: their sound and story. (He speaks French fluently although "tres bizarre" by his own admission.)

Brendan's knowledge of literature is in fact extremely broad and his judgment of his fellow writers most generous and oddly devoid of the particularism and opinionatedness so often associated with writers. Generous, thoughtful and sensitive, this the amazing reverse of a character who so often shows himself as being rowdy and rough, obscene and hilarious.

Once during the several days we saw him while Brendan seemed sunk in a Guinness—or was it "meditation"—in the dining- room of his house in Dublin. I was whispering to his wife, Beatrice, how sorry I was to have so little time to see anything of the country outside Dublin. I heard him grumble some inarticulate sounds and saw him wander from the room. Within minutes a taxicab was honking away in front of the house and without quite knowing what was happening we were bundled out and hurled into the car and started off at full speed. In no time at all we were on our way out towards Dun Laoghaire and Dalkey and his brief comments on the landscape were enough to show the joy he felt in his treasured island.

We passed peaceful misty sloping fields and went up and up and soon we reached the mountain top and came to the inevitable bar where we sat over the inevitable high glasses, among the no less familiar exchange of nods and winks—(Brendan says the reasonable facsimile of "Hi" in Gaelic to everybody in Dublin from the poor Irish lads selling papers to the astonished tourists, nuns, priests and the most dejected Waiting For Godotlike characters). Then Brendan began to sing for a public quietly drinking at the bar and for a group of fair- faced children outside pressing their noses against the window panes. He sang from his enormous repertoire including many Napoleonic hymns—in his own Irish translations—seasoning them all with the peculiar brand of commentary which—as you will soon discover on this record—is uniquely his own, uniquely unorthodox and uproariously funny.

LUCE ARTHUR KLEIN