|

|

|

| more images |

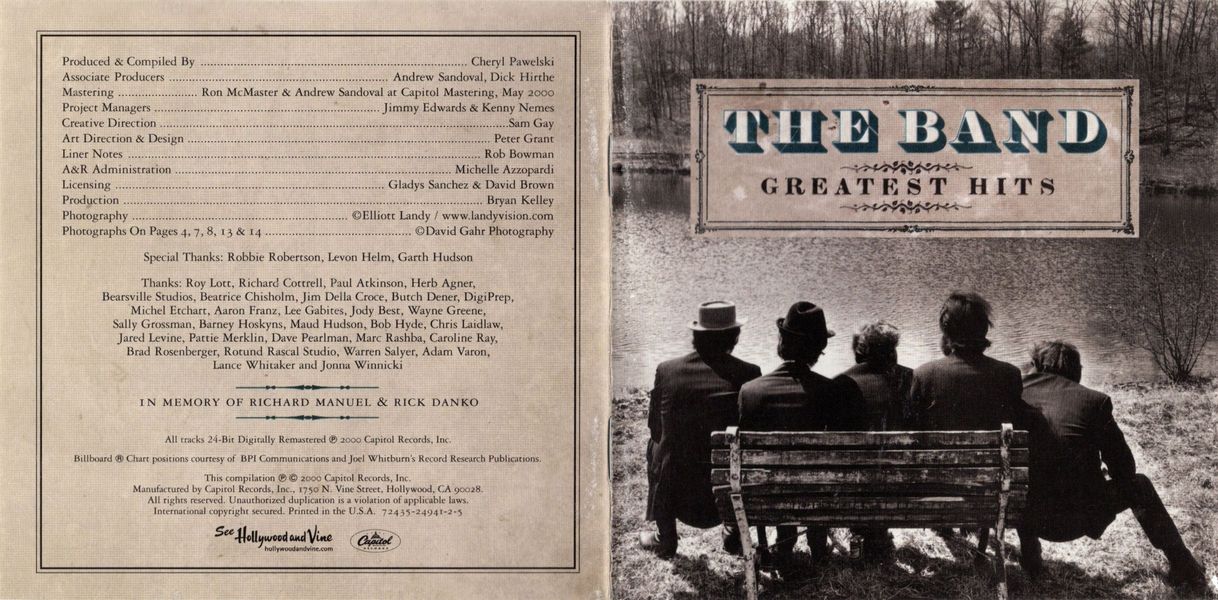

Sleeve Notes

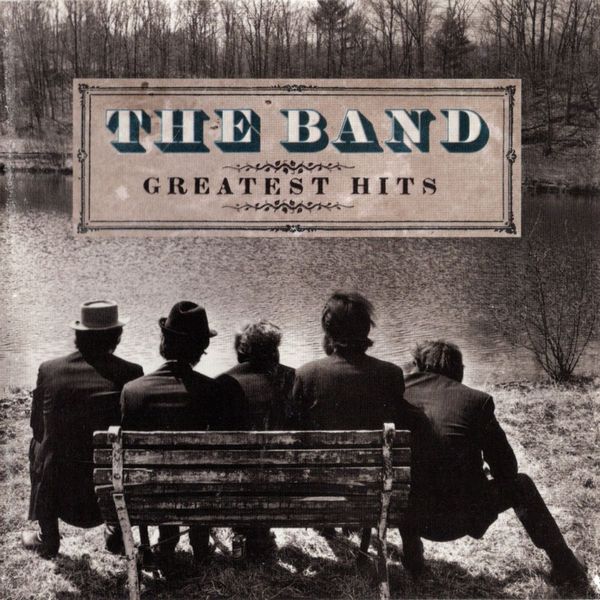

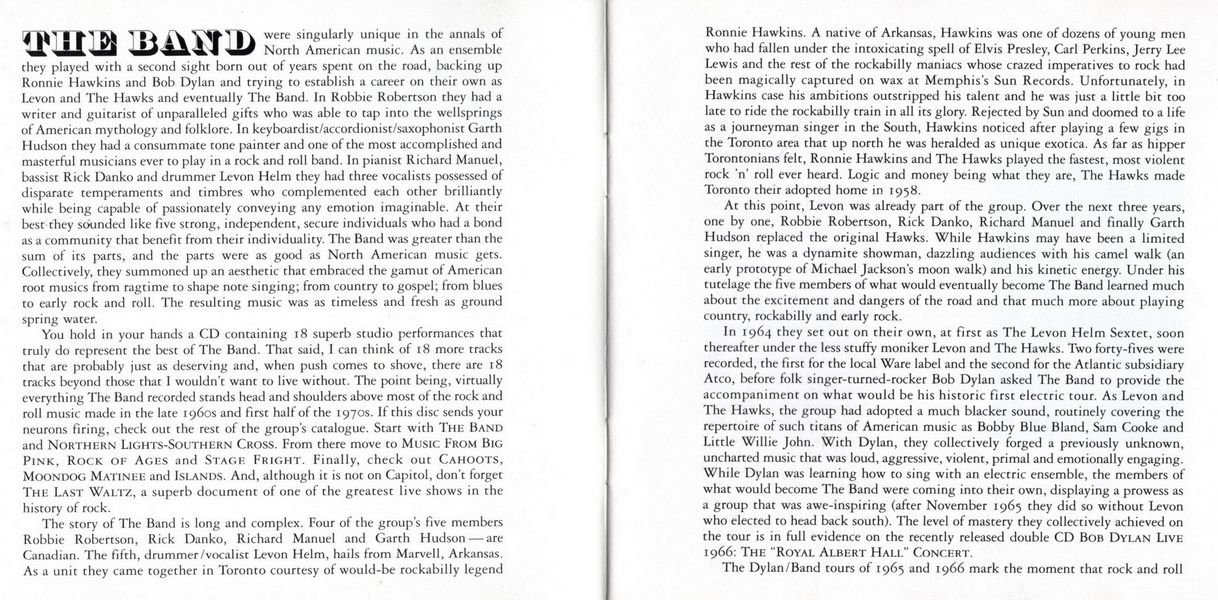

The Band were singularly unique in the annals of North American music. As an ensemble they played with a second sight born out of years spent on the road, backing up Ronnie Hawkins and Bob Dylan and trying to establish a career on their own as Levon and The Hawks and eventually The Band. In Robbie Robertson they had a writer and guitarist of unparalleled gifts who was able to tap into the wellsprings of American mythology and folklore. In keyboardist/accordionist/saxophonist Garth Hudson they had a consummate tone painter and one of the most accomplished and masterful musicians ever to play in a rock and roll band. In pianist Richard Manuel, bassist Rick Danko and drummer Levon Helm they had three vocalists possessed of disparate temperaments and timbres who complemented each other brilliantly while being capable of passionately conveying any emotion imaginable. At their best they sounded like five strong, independent, secure individuals who had a bond as a community that benefit from their individuality. The Band was greater than the sum of its parts, and the parts were as good as North American music gets. Collectively, they summoned up an aesthetic that embraced the gamut of American root musics from ragtime to shape note singing; from country to gospel; from blues to early rock and roll. The resulting music was as timeless and fresh as ground spring water.

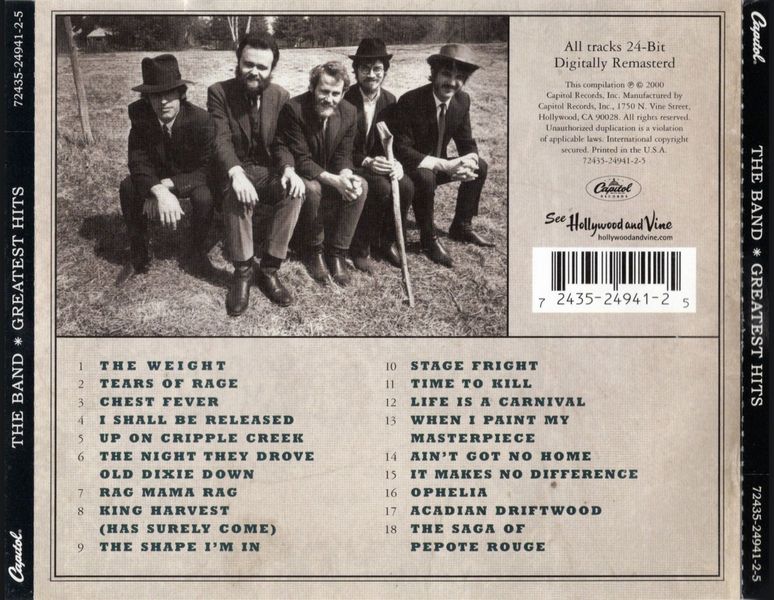

You hold in your hands a CD containing 18 superb studio performances that truly do represent the best of The Band. That said, I can think of 18 more tracks that are probably just as deserving and, when push comes to shove, there are 18 tracks beyond those that I wouldn't want to live without. The point being, virtually everything The Band recorded stands head and shoulders above most of the rock and roll music made in the late 1960s and first half of the 1970s. If this disc sends your neurons firing, check out the rest of the group's catalogue. Start with The Band and Northern Lights-Southern Cross. From there move to Music From Big Pink, Rock of Ages and Stage Fright. Finally, check out Cahoots, Moondog Matinee and Islands. And, although it is not on Capitol, don't forget The Last Waltz, a superb document of one of the greatest live shows in the history of rock.

The story of The Band is long and complex. Four of the group's five members Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel and Garth Hudson — are Canadian. The fifth, drummer/vocalist Levon Helm, hails from Marvell, Arkansas. As a unit they came together in Toronto courtesy of would-be rockabilly legend Ronnie Hawkins. A native of Arkansas, Hawkins was one of dozens of young men who had fallen under the intoxicating spell of Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis and the rest of the rockabilly maniacs whose crazed imperatives to rock had been magically captured on wax at Memphis's Sun Records. Unfortunately, in Hawkins case his ambitions outstripped his talent and he was just a little bit too late to ride the rockabilly train in all its glory. Rejected by Sun and doomed to a life as a journeyman singer in the South, Hawkins noticed after playing a few gigs in the Toronto area that up north he was heralded as unique exotica. As far as hipper Torontonians felt, Ronnie Hawkins and The Hawks played the fastest, most violent rock 'n' roll ever heard. Logic and money being what they are, The Hawks made Toronto their adopted home in 1958.

At this point, Levon was already part of the group. Over the next three years, one by one, Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko, Richard Manuel and finally Garth Hudson replaced the original Hawks. While Hawkins may have been a limited singer, he was a dynamite showman, dazzling audiences with his camel walk (an early prototype of Michael Jackson's moon walk) and his kinetic energy. Under his tutelage the five members of what would eventually become The Band learned much about the excitement and dangers of the road and that much more about playing country, rockabilly and early rock.

In 1964 they set out on their own, at first as The Levon Helm Sextet, soon thereafter under the less stuffy moniker Levon and The Hawks. Two forty-fives were recorded, the first for the local Ware label and the second for the Atlantic subsidiary Atco, before folk singer-turned-rocker Bob Dylan asked The Band to provide the accompaniment on what would be his historic first electric tour. As Levon and The Hawks, the group had adopted a much blacker sound, routinely covering the repertoire of such titans of American music as Bobby Blue Bland, Sam Cooke and Little Willie John. With Dylan, they collectively forged a previously unknown, uncharted music that was loud, aggressive, violent, primal and emotionally engaging. While Dylan was learning how to sing with an electric ensemble, the members of what would become The Band were coming into their own, displaying a prowess as a group that was awe-inspiring (after November 1965 they did so without Levon who elected to head back south). The level of mastery they collectively achieved on the tour is in full evidence on the recently released double CD Bob Dylan Live 1966: The "Royal Albert Hall" Concert.

The Dylan/Band tours of 1965 and 1966 mark the moment that rock and roll became the more mature, complex and artful music known as rock; when pop entertainers were transformed into rock artists; and when the music ceased to be primarily dance-based and instead became a listener-based art. The Band's own career would soon epitomize the best that this new paradigm was capable of offering.

When Dylan came off the road in May 1966, he retreated to a small arts colony in upstate New York called Woodstock. His manager, Albert Grossman, had earlier established a home there and The Band would soon follow. Much of 1967 was spent recuperating, in Dylan's case from a near fatal motorcycle accident; for The Band from almost six straight years on the road. Living upstate proved to be healthy for everyone, physically, psychologically and musically, much of the year spent leisurely gathering each afternoon at a house that Garth, Rick and Richard had rented that became affectionately known as Big Pink. There in the basement, Dylan, Robbie, Rick, Richard and Garth spent day after day writing and playing music. The songs performed spanned the spectrum of roots American music, including Johnny Cash, Mississippi Sheiks and Howlin' Wolf, while the original material ranged from the surreal to the sublime. At least five hours of this music has emerged both officially and on bootlegs under the sobriquet The Basement Tapes. Taken as a whole, these sessions comprise the missing link between the rockabilly, blues, country and R&B that The Band had played with Hawkins, Dylan and as Levon and The Hawks and the music that The Band would make beginning with Music From Big Pink.

Albert Grossman became The Band's manager during The Basement Tapes period. Known within the industry as "The Bear," Grossman quickly inked the group to a deal with Capitol Records (under the name The Crackers!). The group then enticed Levon back into the fold and, with producer John Simon in tow, headed into the studio in January 1968 to record one of the most impressive, mysterious and enigmatic debuts in popular music. Four songs have been selected for thi sgreatest hits anthology from Music From Big Pink: The Weight, Tears Of Rage, Chest Fever and I Shall Be Released. Dylan wrote the latter and co-wrote Tears Of Rage with Richard Manuel. Robbie Robertson penned The Weight and Chest Fever.

As with every Band recording, each song from Big Pink has its own feeling, its own temperament. The languid, slow Richard Manuel-Bob Dylan ballad Tears Of Rage was very deliberately positioned as the lead track on side one on the original LP. At the time no one opened an album with a slow song. It was Robbie's idea to do this, his logic being that Tears Of Rage sounded so unique that it would immediately let the world know that this, indeed, was a different sounding ensemble.

The first sound one hears is Robertson's guitar fed through a black box that Garth had built which gave the guitar a swirling Leslie-speaker-like effect in tandem with Hudson's organ and Helm's severely deadened tom-toms (John Simon wonderfully describes Helm as a "bayou folk drummer.") Richard Manuel delivers an absolutely emotion-filled vocal that describes a parent's heartbreak in a deeply anguished way. From Robbie Robertson's perspective, "It's the most heartbreaking performance Richard ever sung in his life."

Rick Danko joins Manuel on the chorus while Garth and John Simon add a deft touch with their sax and baritone horn lines coming in at the end of the first verse. Levon halves the time, masterfully demonstrating his ability on slow songs of keeping the groove suspended as if in mid-air. The track always seems to be on the verge of stopping but, of course, never does.

I Shall Be Released closed Music From Big Pink. Richard Manuel gave it a falsetto treatment from beginning to end. The harmony on the chorus is a perfect example of the characteristic Band vocal blend — Manuel on the top, Danko in the middle and Helm on the bottom. One of the key components to The Band's sound was the inordinate amount of attention they spent on both vocal and instrumental color. For the background keyboard sounds on I Shall Be Released, Garth fed a Roxochord through a wah-wah pedal so that the sound sweeps up very slowly through the harmonics and then back down again. The snare sound was John Simon's idea, as Levon turned his snare drum upside down and rippled his fingers through the actual snares on the bottom of the instrument.

The two Robbie Robertson compositions included here from Big Pink, Chest Fever and The Weight, continued to be focal points throughout The Band's career. They are near polar opposites of each other. The Weight became a signpost of the time. Featured in the film Easy Rider (but not on the soundtrack album due to contractual restrictions), it was partially inspired by the work of Spanish filmmaker Luis Bunuel.

"He did so many films on the impossibility of sainthood," explains Robertson, "people trying to do good in Viridiana and Nazarin, and it's impossible to do good. In The Weight it's the same thing. Someone says, ‘Listen, will you do me this favor? When you get there will you say "hello" to somebody or will you pick up one of these for me?' ‘Oh, you're going to Nazareth, that's where the Martin guitar factory is. Do me a favor when you're there.' So the guy goes and one thing leads to another and it's like, ‘Holy shit, what has this turned into? I've only come here to say "Hello" for somebody and I've got myself in this incredible predicament.'"

Opening with Robbie on acoustic guitar playing a lick that is part Curtis Mayfield and part country, the track is one of absolute majesty. Garth plays the piano, Levon takes the lead vocal for the first three verses, while Rick assumes responsibility for the fourth verse. Richard contributes breathtaking high falsetto moans after each chorus. (Manuel similarly contributes wordless background parts to In A Station and Caledonia Mission.) Levon and Richard team up to bring it home in the fifth and final verse.

Chest Fever was written as a reaction to The Weight. It was what Robbie refers to as a "vibe" song: "At the time I'm thinking," he laughs, "‘Wait a minute, where are we going here with Bunuel and all of these ideas and the abstractions and all of the mythology?' This music, for us, started as something that felt good and sounded good. Chest Fever was like, here's the groove, come in a little late. Let's do the whole thing so it's like pulling back and then gives in and kicks in and goes with the groove a little bit. If you like Chest Fever it's for God knows what reason—it's just in there somewhere, this quirky thing. Because it doesn't particularly make any kind of sense in the lyrics, in the music, in the arrangement, in anything!"

The beginning of Chest Fever always remained a showcase for Garth Hudson. On the recorded version he commences with the opening motive from Bach's Toccata and Fugue in D Minor. "After that," smiles Garth, "it becomes more unqualifiable, more ethnic." Garth's intro over the course of dozens of live performances eventually evolved into what became known as "The Genetic Method," a tour-de-force of sound, quotation and technique unrivaled in the history of rock.

In the middle the whole piece breaks down and one hears an out-of-tune Salvation Army band (Hudson on sax, John Simon on baritone, Danko on violin). Echoing Robertson's comments above, this touch doesn't make any sense, but it works, invoking one more distant memory of Americana. It also serves as intentional relief so that when the group comes back into the song proper after Levon hollers "very much longer" the groove is that much more powerful. The lyrics were originally "dummy words" to be finished later but "we got kind of used to doing them," remembers Robbie. "It became that's what it is, no more and no less."

While Music From Big Pink was a superior debut and received immediate and sustained critical acclaim, the group's follow-up, simply entitled The Band, proved to be their masterpiece. Released in the fall of 1969, among its many highlights were Up On Cripple Creek, The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, Rag Mama Rag and King Harvest. All were written by Robbie Robertson.

The lead single from the album, Up On Cripple Creek, was the group's first and only Top 30 hit, peaking at #25 in late 1969. It is one of several songs on The Band that had an "old timey" feel brought about by surprising effects. The dominant sound is that of a jew's harp, achieved by Garth with a wah-wah pedal on his clavinet. The astute listener will also notice a heavy emphasis on the bottom end, with Rick's bass and Levon's bass drum being particularly strong and resonant in the mix.

As with Up On Cripple Creek, Rag Mama Rag is basically a fun, uptempo song, sung by Levon, about a rather curious, mind-twisting woman. When Robbie brought the song to the rest of the group, the arrangement was totally up in the air. Rick ended up playing fiddle (doubled an octave higher), Garth contributed the heavily syncopated funky piano line, Levon played mandolin, Richard flailed away at the drums and John Simon (who by this point was nearly a sixth member of The Band) came up with the rag-like bass part on tuba, of all things. The most amazing thing is that he had never played a tuba before and did the track perfectly in one take!

"With Rag Mama Rag," reminisces Robbie, "it was like we were gathering things. We had this basic thing and then, ‘Oh what about if Garth played the piano on this, what about if we do the intro on violin and ‘cause you're playing violin, you can't play the bass. It's a ragtime thing so what about this tuba taking the place of the bass.' So, they would start to add up, the bits and pieces. ‘What about if Richard played the drums on it in that kind of funny style he has.' It's ideas coming until you get the character. All of a sudden it's like, ‘Oh, this is starting to sound like what the song [is supposed to sound] like. We're starting to get a match here.'"

Rag Mama Rag is one of many delights on The Band and remained a staple of the group's concert repertoire throughout their career. The highlight comes on the bridge after the piano solo, where everyone kicks into overdrive. Levon's vocal is doubled by Richard, someone adds something that sounds like a harp and they all nearly enter the stratosphere before the last chorus brings everyone back to reality. Interestingly, the song ended up being a hit in the United Kingdom, peaking at #16 in the spring of 1970.

Robbie finished the writing of Up On Cripple Creek and wrote Rag Mama Rag from beginning to end in Los Angeles while the recording sessions were in progress. At least one song, The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, had been in the works for months.

"I had the music in my head for The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," Robbie related to me in the summer of 2000, "and had no idea what the song was about. I was just humming it and playing these chords and I liked the chord progression that I'd come up with. At some point the concept blurted out of me. Then I went and I did some research and I wrote the lyrics to the song.

"When I first went down south I remember that a quite common expression would be ‘Well don't worry, the South's gonna rise again.' At one point when I heard it I thought it was kind of a funny statement and then I heard it another time and I was really touched by it. I thought, ‘God, because I keep hearing this, there's pain here, there is a sadness here.' In Americana land, it's kind of a beautiful sadness.

"In one of the verses I mentioned something about Lincoln in there and Levon said, ‘You can't do that.' I said, Really? I was just reading this book...' From the Southern point of view it was ‘Hey, this is the guy that was trying to tell us we can't have slaves.' So, Levon just wised me up to that. He was like, ‘You've got to watch that because in the South that wouldn't necessarily go down well!' Then he explained to me the politics of that period in a Cracker fashion that I understood. ‘Oh, I see what you mean.' That was his contribution to the song."

The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down is one of Robertson's best songwriting efforts. Dealing with the end of the Civil War from the South's point of view, the song gives voice to several thousand anonymous people's stories. Levon, being the southerner in the group, was able to impart a wholly believable conviction to the vocal. The song is also one of the best examples of his "hiccup" bass drum patterns. On the second verse, a harmonica seems to enter the picture. This is Garth up to his mischief again, overdubbing a Hohner melodica on top of an accordion sound generated by his Lowrey organ (he used a Lowrey almost exclusively as opposed to the more common Hammond B-3).

"Garth was a universe unto himself back there," muses John Simon. "It's become now that keyboard players have to build their own instruments. Garth was in the vanguard of this and reveled in it and loved it." Garth also contributed a little trumpet towards the end.

King Harvest closed The Band album. The song is one of Robbie's most evocative, describing the plight of one caught between the past and the present, the country and the city, nature and humanity. The attention to musical as well as lyrical detail is, as always, impressive with the chorus being quieter than the verse, exactly the opposite of nearly every other song ever written.

John Simon is playing electric piano on the track through the same black box with the Leslie-speaker effect that Robbie had used to open Tears Of Rage on Music From Big Pink. When asked about these nuances of sound, without hesitation John Simon responded, "Robbie was the Duke Ellington of this band. Robbie was the one whose vision was being satisfied for the most part!"

A self-described Soldier of Fortune on lead guitar with Hawkins and Dylan, on Music From Big Pink Robbie had deliberately avoided playing a single guitar solo. For the most part, The Band was also light on guitar pyrotechnics. When Robbie did take a solo, such as that on King Harvest, it was marked by economy, restraint and understatement.

"This was the new way of dealing with the guitar," Robbie told me. "This was very subtle playing, leaving out a lot of stuff and just waiting until the last second and then playing the thing in just the nick of time. It was an approach to playing where it's so delicate. It's the opposite of the ‘in your face' guitar playing that I used to do. This was the kind of thing that was slippery. It was like you have to hold your breath while playing these kinds of solos. You can't breathe or you'll throw yourself off. I felt emotionally completely different about the instrument."

The end of King Harvest is one of Robbie's finest moments as a guitarist. It is living proof that less is indeed often more.

The Band had been recorded in a makeshift studio in the pool house of a sprawling mansion the group had rented in Los Angeles. For their third album, 1970's Stage Fright, the group decided to record in another makeshift studio, this time constructed in a small, old wooden theatre, The Woodstock Playhouse. By this point the group had achieved a measure of fame and fortune. The price of such success proved to be steep as various members of the group had become involved with drugs, and a certain degree of paranoia and ennui had begun to infect what had been an incredibly close-knit brotherhood of like-minded musicians. The three songs selected for inclusion here from Stage Fright, The Shape I'm In, Stage Fright itself and Time To Kill, all rather accurately reflect the fractured state of the group at the time of the recording sessions in June 1970.

The album's centerpiece was its title song. Positioned as the second-to-last track on the original vinyl issue, Stage Fright provides the context for one of the finest vocal performances of Rick Danko's life. Also of note on the track is Levon's wonderfully unpredictable playing on his ride cymbal.

"It was named after the experience of having put ourselves in the public eye," relates Robbie, "but we were kind of private people at the same time. Taking our music out and performing it, there was something very private about it and the way that we performed it was not very flashy or showy. We just came for business so we could go on and play our hearts out. There was some kind of a yin-yang between our nature and what concerts really were. It was almost more like classical music in performance than it was of coming out and wearing cut-off leotards and buckskins. We're not here for nonsense. We're not here for people to get drunk while we re playing anymore. We wanted to shed that skin. It all added up to this kind of Stage Fright thematic thing in our lives. It became so vulnerable and sensitive presenting this music in public."

As was true of much of the album, the song Stage Fright is devoid of the ensemble singing that had been such a strong and rich part of The Band's identity on their first two LPs. No longer did Rick, Levon and Richard jump in at will, echoing and responding to each other's phrases, singing in their characteristic together-but-not-together, carefree, go-for-broke manner. The vocal performances on Stage Fright were still incredibly powerful but, by and large, they were solo efforts.

Stage Fright remained a staple of The Band's concert repertoire right up to the end as did the two songs that comprised the single from the album, Time To Kill and The Shape I'm In. Time To Kill features yet more invigoratingly unpredictable cymbal work from Levon and a vocal duet by Danko and Manuel. The Shape I'm In opened up side two of the original album and, despite being a raucous stomp fueled by a great Rick Danko bass line and coloration galore from Garth, said more about The Band, and in particular lead singer Richard Manuel, than some might have realized.

The Band's fourth album, 1971's Cahoots, was the first time that the group conceived of and developed an album from beginning to end in a regular recording studio. As with The Band and Stage Fright, the material on Cahoots was unified by an overriding theme, in this case a regret at the passing of things that had once been of considerable value for individuals and communities across the continent.

The astonishingly powerful and propulsive Life Is A Carnival opened the album. It was also released as a single and was the only song on Cahoots to remain a staple of the group's live repertoire right through their final concert. The metaphor that underpins the song is superb and is cleverly supported by a highly layered accompaniment sporting one of Rick Danko's funkiest bass lines. (He had started playing fretless bass a year earlier, once more expanding the sonic resources of The Band.) The biggest lift, though, is the horn line, courtesy of legendary New Orleans R&B producer Allen Toussaint.

Both Robbie and drummer Levon Helm had been enamored with the slew of hits Toussaint had produced in the 1960s by such Crescent City artists as Jesse Hill, Ernie K-Doe, Lee Dorsey, Clarence "Frogman" Henry, Aaron Neville and Irma Thomas. More recently they had been knocked out by Toussaint's production and arrangements on Lee Dorsey's 1970 Yes We Can album and were very excited at the prospect of working with him. "I called him up," smiled Robbie, "and I thought, ‘Geez, I'm gonna have to start from scratch with this guy.' I said, ‘My name is Robbie Robertson and I work with this group, The Band.' He said, ‘Oh yeah, I know your music well.' He was such a savvy guy, such a curious, well-informed, sophisticated, musically adventurous minded guy."

Robertson sent the completed track down to New Orleans where Allen began to craft the impossibly funky horn lines. "The instrumentation was different from what I'd previously used," Toussaint told Barbara Charone in 1973, "but I talked it over with Robbie. In fact, it would have been a completely different arrangement if I hadn't talked it over with him. ‘cause I can remember I wrote the arrangements first, and as we talked I started tearing them up!"

While every aspect of Toussaint's horn chart was nothing short of inspired, the highlight is in the middle where he arranged brass and reeds in and around Robbie's high-wire electric lead. The whole section sounds so organic, you'd swear it had to be recorded in real time with Robbie and the horns playing off one another. The fact is, the guitar solo had been played some time before on the original track cut at Bearsville Studio in Woodstock and Allen had simply written perfectly complementary parts. The whole performance added up to quirky, bubbling, contrapuntal New Orleans funk at its best.

"It was great," Robbie fondly recalled, "because the horns didn't all play together. Other people would write horns and everybody would come in and everybody would go out in unison. They would all start and stop at the same time. This thing was all, ‘You play this, he plays that, you answer this and then you come under that, then you two guys come in here.' With Allen's thing, everybody's play separately. It was very much like The Band in a way! It's kind of like a Dixieland approach."

In the midst of the sporadic sessions for the album, Bob Dylan came by Robbie's house and the two friends spent an afternoon hanging out at the painting studio next door. After Robbie played Dylan some of the songs that The Band were already working on, he asked Bob whether he had any material that might be appropriate for the album. Dylan proceeded to play an embryonic version of the still unfinished When I Paint My Masterpiece. Inspired by Robbie's enthusiasm, Dylan completed the song shortly thereafter. Levon's mandolin and Garth's accordion lend the song a European feel that is perfectly in keeping with the lyric, their break after the first verse being especially descriptive. As per usual when Levon played mandolin, Richard Manuel took over the drum chair.

When Cahoots was released in the fall of 1971, The Band followed it up with a short U.S. tour that culminated in a series of four shows at the Academy of Music in New York City on the last four nights of the year. Allen Toussaint had been hired to provide horn arrangements for much of The Band's earlier repertoire, and the shows were played with the cream of New York's horn players. A double live album, Rock of Ages, was culled from these performances. Released in 1972, it remains one of the most invigorating live albums ever released.

At this point The Band entered an extended hiatus, neither recording nor playing live in 1972. In 1973 they played only three gigs but they did manage to record an oldies album, Moondog Matinee, as well as back Bob Dylan on his Planet Waves album. The latter sessions occurred in the fall while Moondog Matinee was recorded intermittently between March and June and mixed in August.

At the time of Moondog Matinee, rock was entering the final months of its first wave of nostalgia. Ever since Sha Na Na had become a minor sensation at Woodstock playing sanitized covers of 1950s rock and pop, artists from the first decade of rock had toured as part of "Revival" packages and various groups had recorded one or more reverent covers of a handful of standards by Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, et al. In characteristic fashion, The Band's approach to an oldies album was somewhat left of center. In the first place, the tunes they selected were predominantly from the R&B side of the equation. Secondly, their covers were neither reverent nor sanitized. In Robbie's words, they were designed to "complement" the originals as The Band simply got inside of each tune and delivered the best version they were capable of.

Clarence "Frogman" Henry's winter 56/57 smash Ain't Got No Home got Moondog Matinee off to a rollicking start. Levon obviously took great delight in singing the "Woo woo woo woo woo" chorus. "We were always very connected to the New Orleans thing," laughs Robbie. "Ain't Got No Home was something we would mess around with. It was fun!"

Dig Garth Hudson's lascivious, raunch-infested '50s-era tenor sax solo. Lee Allen and Herb Hardesty look out! Billy Mundi, formerly of the Mothers of Invention, plays drums while Levon plays bass. For the "frog"-voiced verse, Garth rigged up a hose that Levon sang through while Garth played along on the keyboard, the composite timbre approximating the sound that Henry achieved on the original recording.

The Band spent the first two months of 1974 on the road with Bob Dylan on what was the latter's first series of shows since 1966. Providing accompaniment for Dylan, as well as playing their own sets on a sustained basis for the first time since the waning days of 1971, The Band proved themselves once again to be among the premier units in the world of rock. After a late summer/early fall series of shows without Dylan, it was time for the group to circle the wagons and record their first new album in four years. The result was 1975's Northern Lights-Southern CROSS set, The Band's finest effort since their second album. For most Band fans, having almost given up on ever seeing new material, the album seemed like a miracle.

Recorded at their new "Shangri-La" studio in Los Angeles, Northern Lights-Southern Cross sported only eight songs but they were all extended in length. Robbie took a number of guitar solos, and Garth seemed to take on a more active role. Equipped with 24 tracks and the new synthesizer technologies, including an RMI computer keyboard, ARP and Roland monophonic solo synths, a mini-Moog, an ARP string ensemble and the new Lowrey Symphonizer, Garth could paint tone colors like never before. On several songs, the keyboard parts alone took eight or nine tracks. Given that it was recorded prior to the advent of computerized mixing, this must have been one hell of an album to finish!

Northern Lights-Southern Cross was a richly evocative masterpiece from which It Makes No Difference, Ophelia and Acadian Driftwood have been selected for The Band's Greatest Hits. The former captures Rick Danko at his most emotional and Robbie's introductory guitar line and solo were probably his best playing on record since King Harvest. Garth played all the horns on the album, contributing a great soprano saxophone part that exquisitely responded to Rick's vocal on the final verse.

Ophelia is somewhat reminiscent of Life Is A Carnival, sporting a good-time New Orleans feel, an old-timey chord progression (1,1117, VI7,117, V7,1 — found in dozens of Tin Pan Alley standards as well as in several Scott Joplin compositions) that Robbie had stumbled upon while fooling around on guitar and an invigorating lead vocal from Levon. Richard ably supported Levon while Garth perfectly complemented the proceedings, playing an array of brass, wind and synthesizer parts.

"It was a song that could have been written in the thirties or it could have been written now," muses Robbie. "I thought this was really true to the heart of The Band. I really liked it when I could write music that ignored time completely. That was coming through to me loud and clear on Ophelia."

Acadian Driftwood was the album's cornerstone. It is one of Robbie's all-time masterpieces, the equal to anything else The Band ever recorded. The song chronicles the story of a people displaced, the Acadians who were exiled from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in the 1750s. (Most of the Acadians eventually made their way to Southwest Louisiana where they became known as Cajuns.) Robbie's ability to create a fictional historical voice that can speak so eloquently for several thousand real ones is a rare and precious gift.

Garth on accordion and guest Byron Berline on fiddle create the appropriate Cajun feel. Richard, Rick and Levon all share the vocal. Richard plays clavinet while Robbie adds an acoustic guitar and Garth further contributes piccolo and bagpipe chanter. To capture the old-time feel of the French at the end, Robbie consulted a Quebecois lyricist and playwright to help with the translation. The net result is as evocative and magical as music ever gets.

Despite the critical and aesthetic success of Northern Lights-Southern Cross, The Band decided to call a halt to touring in the fall of 1976, winding things up with what became known as The Last Waltz at Winterland in San Francisco. A triple LP from that show was eventually released on Warner Brothers. In the meantime, The Band were simultaneously feverishly working on the final studio album that they owed Capitol. Released in April of 1977 Islands was a bit of a hodgepodge, including a couple of covers, some songs that had been started as early as 1973 and some brand new material. The Saga Of Pepote Rouge was one of the best songs on the album. Sung by Rick, the song's lyric presents a cryptic mythological tale — to this day Robbie has no clue as to where it came from.

"It's like [Carlos Castaneda's] The Teachings of Don Juan," he offers. "It's story telling, it's fairy tale-ish, it's mythological. Who of us isn't a sucker for that stuff? It was just one of those things where it caught me off guard and took me somewhere that I didn't even know I was going. But I was glad to take the trip."

With Islands and The Last Waltz The Band's career came to a close. Although the latter was supposed to only signal the end of touring, and as late as two years later various Band members were still talking about the "next" album, further studio LPs did not materialize.

In the ensuing years Rick Danko, Levon Helm and Robbie Robertson would all record solo albums and Garth Hudson worked his wizardry for any number of other artists in the studio. In the early 1980s Rick, Richard, Garth and Levon reunited, touring and eventually recording once again under the name The Band. But with Robbie Robertson not part of the mix, it simply wasn't the same. Tragically Richard committed suicide in 1986 and Rick Danko died in late 1999, spelling the end to even a reincarnated version of The Band.

In the end, the group's story is one of teamwork. John Simon refers to the members of The Band as "wonderfully selfless and wonderfully pragmatic." Individually and collectively they would do whatever was appropriate for each song. No one rock and roll group before or since has displayed this amount of instrumental versatility, and few have ever paid as much attention to minute details for every instrument on every song.

Their legacy is a body of recorded performances that is as timeless as the music that originally inspired them. What was moving about their recordings 25 and 30 years ago is equally moving today. Listen to the work of many of their contemporaries and see if you can say the same thing. In the meantime, go on and check out the rest of their catalogue. There are innumerable gems yet to behold.

Rob Bowman, August, 2000

All quotes contained within these liner notes, unless specifically attributed otherwise, are from personal interviews conducted by Rob Bowman over the last twelve years with members of The Band and John Simon. Rob would like to express his thanks to all for the many hours of their time.