|

|

|

| more images |

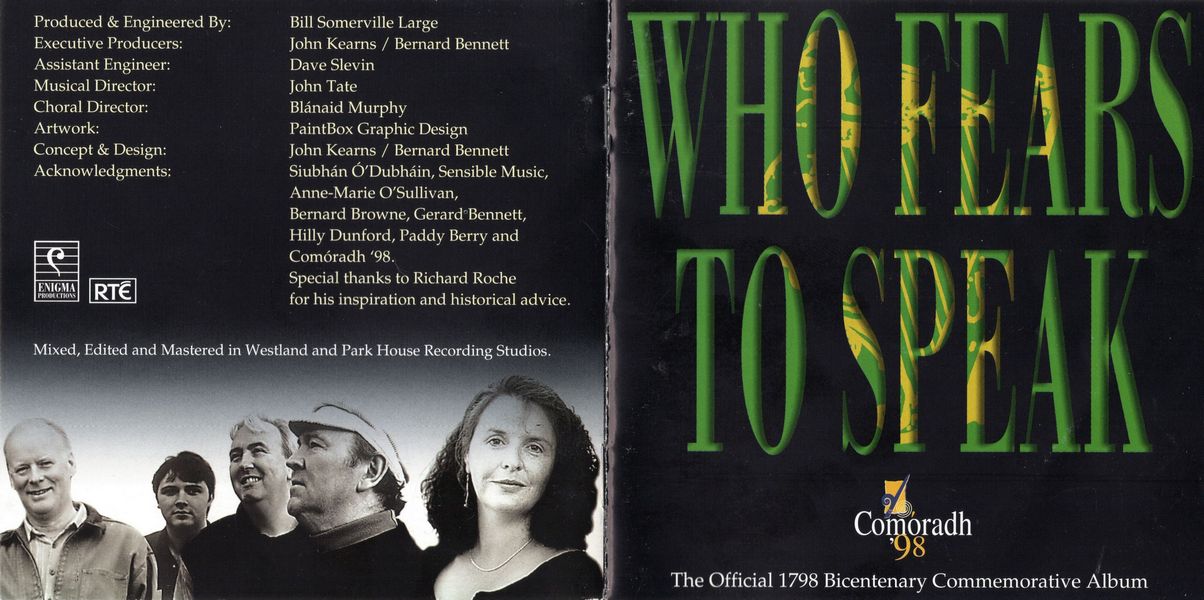

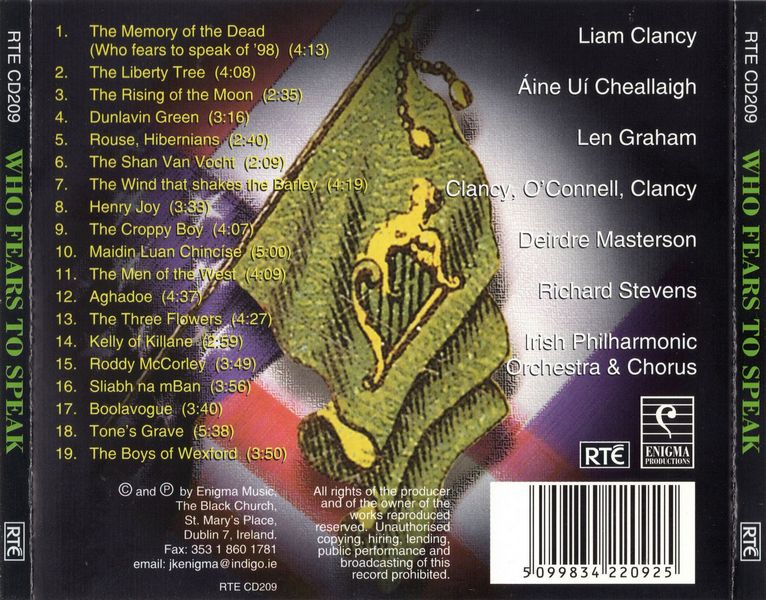

Sleeve Notes

"There exists in this Kingdom a traitorous conspiracy by persons calling themselves United Irishmen."

Lord Camden 1797

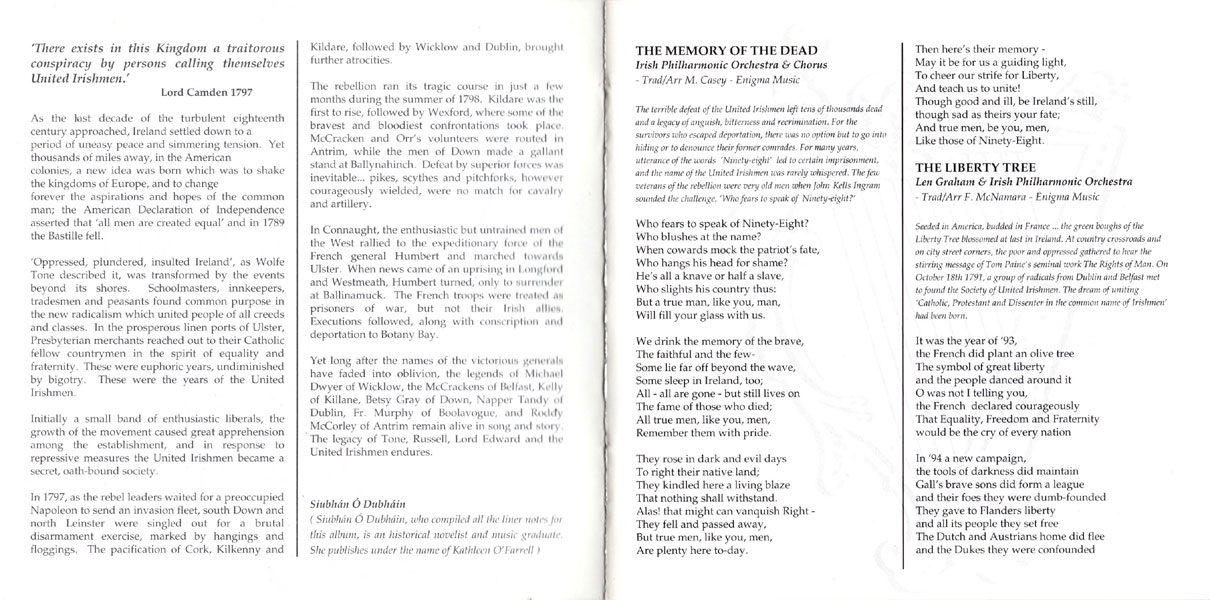

As the last decade of the turbulent eighteenth century approached, Ireland settled down to a period of uneasy peace and simmering tension. Yet thousands of miles away, in the American colonies, a new idea was born which was to shake the kingdoms of Europe, and to change forever the aspirations and hopes of the common man; the American Declaration of Independence asserted that 'all men are created equal' and in 1789 the Bastille fell.

'Oppressed, plundered, insulted Ireland', as Wolfe Tone described it, was transformed by the events beyond its shores. Schoolmasters, innkeepers, tradesmen and peasants found common purpose in the new radicalism which united people of all creeds and classes. In the prosperous linen ports of Ulster, Presbyterian merchants reached out to their Catholic fellow countrymen in the spirit of equality and fraternity. These were euphoric years, undiminished by bigotry. These were the years of the United Irishmen.

Initially a small band of enthusiastic liberals, the growth of the movement caused great apprehension among the establishment, and in response to repressive measures the United Irishmen became a secret, oath-bound society.

In 1797, as the rebel leaders waited for a preoccupied Napoleon to send an invasion fleet, south Down and north Leinster were singled out for a brutal disarmament exercise, marked by hangings and floggings. The pacification of Cork, Kilkenny and

Kildare, followed by Wicklow and Dublin, brought further atrocities.

The rebellion ran its tragic course in just a few months during the summer of 1798. Kildare was the first to rise, followed by Wexford, where some of the bravest and bloodiest confrontations took place. McCracken and Orr's volunteers were routed in Antrim, while the men of Down made a gallant stand at Ballynahinch. Defeat by superior forces was inevitable... pikes, scythes and pitchforks, however courageously wielded, were no match for cavalry and artillery.

In Connaught, the enthusiastic but untrained men of the West rallied to the expeditionary force of the French general Humbert and marched towards Ulster. When news came of an uprising in Longlord and Westmeath, Humbert turned, only to surrender at Ballinamuck. The French troops were treated as prisoners of war, but not their Irish allies Executions followed, along with conscription and deportation to Botany Bay.

Yet long after the names of the victorious generals have faded into oblivion, the legends of Michael Dwyer of Wicklow, the McCrackens of Belfast, Kelly of Killane, Betsy Gray of Down, Napper Tandy of Dublin, Fr. Murphy of Boolavogue, and Noddy McCorley of Antrim remain alive in song and story. The legacy of Tone, Russell, Lord Edward and the United Irishmen endures.

Siubhán Ó Dubháin

(Siubhán Ó Dubháin, who compiled all the liner notes for this album, is an historical novelist and music graduate. She publishes under the name of Kathleen O'Farrell)

The Memory of The Dead — The terrible defeat of the United Irishmen left tens of thousands dead and a legacy of anguish, bitterness and recrimination. For the survivors who escaped deportation, there was no option but to go into hiding or to denounce their former comrades. For many years, utterance of the words 'Ninety-eight' led to certain imprisonment, and the name of the United Irishmen was rarely whispered. The few veterans of the rebellion were very old men when John Kells Ingram sounded the challenge, 'Who fears to speak of Ninety-eight?'

The Liberty Tree — Seeded in America, budded in France … the green boughs of the Liberty Tree blossomed at last in Ireland. At country crossroads and on city street corners, the poor and oppressed gathered to hear the stirring message of Tom Paine's seminal work The Rights of Man. On October 18th 1791, a group of radicals from Dublin and Belfast met to found the Society of United Irishmen. The dream of uniting 'Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter in the common name of Irishmen' had been born.

The Shan Van Vocht — This title comes from the Irish "poor old woman" (Seán Bhean Bhocht), an allegorical name for Ireland. For centuries Irish eyes turned toward the sea in expectation of a French sailing fleet. France, the final destination of Ireland's bravest exiles, the Wild Geese, was the last hope of those, like the poor old woman, who had lost all hope for themselves. In December 1796 a French fleet carrying fourteen thousand men sailed for Ireland, under the command of General Hoche. His ship became separated from the others, but as the fleet waited in Bantry Bay it was dispersed by a storm. The bitterly disappointed United Irishmen waited for years for the French to sail again.

The Wind That Shakes The Barley — Leaving the grave of his true love, who was shot by the enemy, a young rebel seeks vengeance. Written by Robert Dwyer Joyce, author of 'The Boys of Wexford', and set to an old Jacobite tune, 'Welcome Royal Charlie'.

Henry Joy — In the prosperous port of Belfast a group of young radicals met in the home of Henry Joy McCracken and his feisty sister, Mary Anne. It was there that Tone, Russell, Nielson, and their companions pledged themselves anew to the cause of the United Irishmen. On June 6th 1798, McCracken led the men of Antrim in rebellion. Sectarian divisions had weakened the rebels, and although Randalstown and Ballymena were captured, they were routed at Antrim town. Henry Joy McCracken was hanged in Belfast.

The Croppy Boy — The cropped hairstyle favoured by the revolutionaries of France soon became fashionable in Belfast, and from hence to other parts of Ireland. It became synonymous with the rebel cause, and led to the derogatory term 'Croppy'. As so often happens, the term of insult became a label of pride, and of the several songs which commemorate the 'Croppy Boy', this is one of the finest.

Maidin Luan Chincíse — A long established poetic custom is employed in this song, 'Whit Monday Morning'. Full of allegory and metaphor, it describes the enemy as a malevolent 'mist' which befalls the small rural community. As in other such songs in the Irish language, one has to peer beneath the surface to find the true meaning.

The Men Of The West — When General Humbert sailed with eleven hundred men from La Rochelle he was met at Killala by an army of Connacht men, strong in courage and enthusiasm, but poorly armed and trained. They took Ballina and moved on to Castlebar, where General Lake's forces had gathered. As the French and their allies charged, the enemy retreated with extraordinary haste… hence, the 'Races of Castlebar.'

Aghadoe — Aghadoe, by John Todhunter is one of the many tales of betrayal and treachery. For money, Shaun Dhum betrays his sister, who was hiding her rebel lover in the glen of Aghadoe in County Cork. The song also refers to the practice of exhibiting the severed heads of executed rebels on the spikes of the prison gates, as a deterrent to others.

The Three Flowers — Three of the most enduring heroes are remembered in this song: the 'father' of Irish republicanism, Theobald Wolfe Tone; Michael Dwyer, who held out for five years in the Wicklow Mountains; and Robert Emmet, younger brother of Thomas Addis Emmet, who led one last valiant rebellion in Dublin in 1803. One feature of 'The Three Flowers' is the aisling tradition of the 'Seán bhean bhocht' (the poor old woman), but this lime, Ireland is personified as a young girl.

Kelly Of Killane — John Kelly led the men of the barony of Bantry. The Shelmaliers were trained from boyhood to shoot seabirds and were thus valued by their comrades as keen marksmen. Kelly was twenty five years old when wounded at the siege of Ross and he was cared for by his sister until his arrest and immediate execution. Tall and golden haired, he was every inch the Celtic hero, and his valour gained the respect even of his enemies.

Roddy MacCorley — One of the many folk heroes who barely merits a mention in the history books, Roddy McCorley's proud march to the scaffold has become legendary in Ulster folklore. He was hanged on Toome Bridge Country Antrim, despite a desperate attempt by the local people to save his life.

Sliabh na mBan — The title of this hauntingly beautiful melody, which inspired O' Riada to include it in Mise éire, is often confused with verses by Charles Kickham, the 19th century patriot. The Irish verses express the heroic courage and pathos of the battle fought on the slopes of Sliabh na mBan (the Mountain of the Women), near Clonmel, County Tipperary, when the poorly armed peasants were defeated.

Boolavogue — The inspiring imagery of blazing heather and billowing flag form a striking background to this account of Fr. John Murphy's campaign In Wexford. The green standard, embroidered with the words 'Liberty or death', was first raised at Boolavogue. After defeating the garrison at Enniscorthy, the jubilant rebel army set up camp on Vinegar Hill where, on June 21st they were surrounded by an army of between fourteen and twenty thousand, supported by artillery. The flag which had flown proudly for four weeks was lowered and the rebellion was all but broken. Fr. Murphy was later arrested at Tullow and executed.

Tone's Grave — On October 12th 1798, a French fleet under General Hardy was intercepted off Tory Island. Among the defeated prisoners was Wolfe Tone, who was captured and taken in chains to Dublin. When charged with treason, he made no denial saying 'The great object of my life has been independence of my country; for that I have sacrificed everything most dear to man.' When his request to meet his death as a soldier, by firing squad, was refused, Tone slashed his throat with a razor, and died on November 19th. He is buried in Bodenstown Churchyard.

The Boys Of Wexford — The greatest threat to the Government undoubtedly came from Wexford and the intensity of the fighting was unequalled anywhere else in Ireland. The stirring marching tune of "The Boys of Wexford" in many ways masks the tragedy of a rebellion, which began with so much hope and ended in a sea of carnage. The aftermath resulted in the Act of Union and a century of political isolation for Ireland. Yet the dream of a nation remained alive in the villages and the countryside, around firesides and in the places where people gathered who dared to speak of ninety-eight …