|

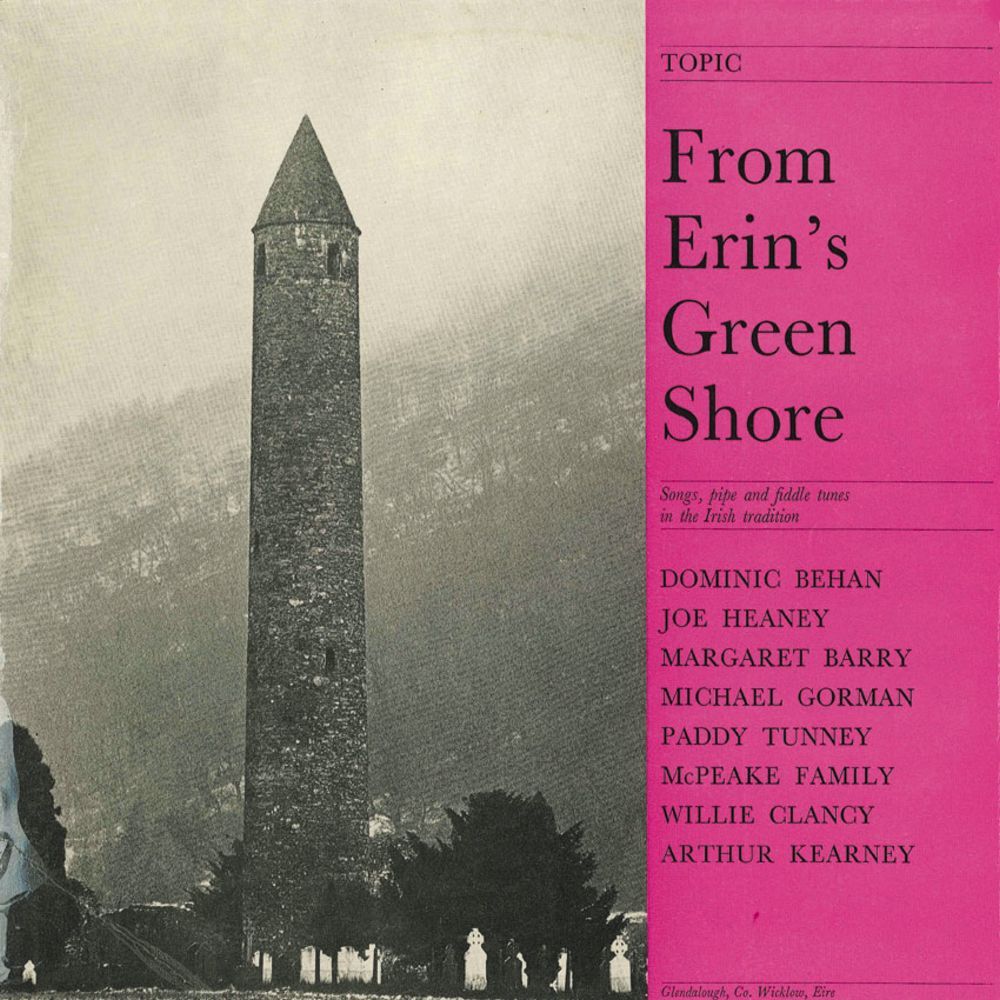

Sleeve Notes

Icham of Irlaunde

ant of the holy lande of irlaunde.

gode sir ant pray ich ye

for of saynte charite

come ant daunce wyt me

in irlaunde.

This blarneying invitation to the dance dates from around 1300; already, the Irish were a musical nation but their troubles were only just beginning.

Some seven hundred blood-stained years later, the republic of Eire has finally and for good turned its back on Great Britain and sets its face resolutely towards America. Hopefully, Granuaile prepares her economic miracle which might at last provide enough work at home to keep her sons on their native shore instead of wandering the world.

The Ireland of the jaunting car, the Galway shawl, the white cabin nestling on the green hillside—this Ireland is fast disappearing as industry, including that specifically twentieth century industry, tourism, pulls the country's standard of living up to the level of the rest of Western Europe.

With the old ways, inevitably, die the old songs and dances except where there is enough love and enthusiasm to keep them alive. That is the way of the world. One deplores the death of so much grace and charm but the Twentieth Century is an inexorable goddess and she is also called Change. Changes everywhere. At a St. Patrick's Day concert, a showband tops the bill; they don stetsons to sing a Country and Western medley, homage to a cowboy songster. A plump youth cavorts, blowing down his saxophone; and could he dance a hornpipe, do you think, that marvellous display of casual agility? The lights dim; a blonde in a sparkly dress stands in a blue spotlight and sings The Dying Rebel to a thumping three/four beat. Her voice is broad enough or sweet enough to sing Her Mantle So Green or the stirring ballad of Willie Fieilly but later she twists as the band plays a Monkees hit. From the stalls, a disgruntled ticket-holder cries: "Why don't you play some of the good old Irish tunes?"

So maybe change will not take everything away; maybe the beauty of the old music will be its claim for survival. For, meanwhile, in Connemara, where the little fields are paved with rocks and the donkeys still pick their way over the bog on delicate hooves, perhaps gnarled hands are tuning a fiddle or an old man throws back his head and closes his eyes and begins to sing an ancient song in the Irish language in the dignified, complicated, old fashioned way. And change stands still and the passage and alterations of time cease to matter.

Wherever the Irish go, they take their music with them, and the Irish go everywhere. You can hear great Irish singing and music in Camden Town. In Birmingham. In Liverpool. In any town where there is a substantial Irish community. A Chicago policeman put together one of the best of all Irish tune books from the playing of Irish American musicians.

"Of all the countries in the world," wrote the late Sir Arnold Bax, "Ireland possesses the most varied and beautiful folk music". The music of this country is as inexpressibly various as the landscape, as stark as the Western shores, as lushly romantic as the green hills of Donegal. And as cheerfully convivial as the smoky interior of a Dublin pub. This record is a musical patchwork quilt of the beauties of Ireland, that most beautiful country.

Here is music of all kinds. For example, the voice of Dominic Behan, poet, playwright, controversy rouser, entertainer extraordinary, with a Dublin street song, The Zoological Gardens, a real echo of that handsome, Guinness soaked city on the Liffey, and also The Castle of Drumboe, commemorating the tragic rising against the English in 1916. This the tough, jaunty, irrepressible voice of the streets of Dublin; and the noble and ornate unaccompanied singing of Joe Heaney is the expression of the Western coast, the essential core of the Irish tradition.

Here the barren landscape of bog and stone provides little enough sustenance for the poor farmers and fishermen who eke out a precarious livelihood there and who still speak Irish Gaelic as their first language. Here, the classical repertory of Irish song has survived from the remote past to the present day. Joe Heaney, native of County Galway, sings a light-hearted love song in the beautiful but fast dying Irish tongue. Little work and less money drove Joe Heaney from Galway; the song Margaret Barry sings, Our Ship is Ready, has words aching with the sadness of the exile who must leave home and loved ones for the sake of bread. The magnificent, roving tune intensifies the heartbreak of the words, "Farewell, my love, and remember me".

Break for music. Michael Gorman and Margaret Barry also live far from home, in London. Michael Gorman is one of the finest of all Irish fiddlers; Margaret Barry is a particularly fine singer but here she accompanies Michael Gorman with her distinctive banjo style while he plays a favourite hornpipe. The Boys of Blue Hill. More music—the virtuoso uillean piper, Willie Clancy, playing the old march, The Chanter's Song. The uilleann (elbow) pipes, are so called because one doesn't play them with the mouth like Scottish bagpipes; instead, the flow of air is maintained by a small bellows strapped under the arm and pressed by the elbow. Unlike the Scottish instrument, the Irish bagpipe is a discreet-toned indoor instrument lending itself to delicate treatment. To round off this selection there is a collection of polkas, where Michael Gorman and Margaret Barry are joined by a group of expatriate musicians to create something of the joyous atmosphere of a ceili band.

And Margaret Barry herself sings My Lagan Love with all the flamboyant sweetness that is the essence of her style. This song she learned from a record of the celebrated Irish tenor, John McCormack; it is a literary production, a poem written by Seosamh McCathmhaiol (Joseph McCall) which the composer. Herbert Hughes, set to an old Gaelic tune. Margaret Barry's voice and style irradiate the florid Victorian diction, turning all to grace.

Another notable singer, standing up for Donegal, is Paddy Tunney, poet and patriot, a fighting son of Erin, giving us a charming jig song notable for its wealth of references to the literary and political idols of nineteenth century Ireland, The Rollicking Boys Around Tandaragee. A fellow rebel of Paddy's, Art Kearney, sings The Song of the Dawn, written by Brian O'Higgins, who fought in the rising of 1916. The song signifies the revival of a nation.

In the capital of the debated six counties, Belfast, in British Ireland, live the multi-instrumental McPeake family, whose sweet harmonies accompanied by the plangent tones of harp and uillean pipe, have become internationally famed. Here, they sing a patriotic Irish song, An Durd Fainne, in the Irish language, and the nostalgic ballad they have made entirely their own. Will Ye Go, Lassie, Go. The picture of a hillside full of flowers is a charming place to end.