|

|

|

Sleeve Notes

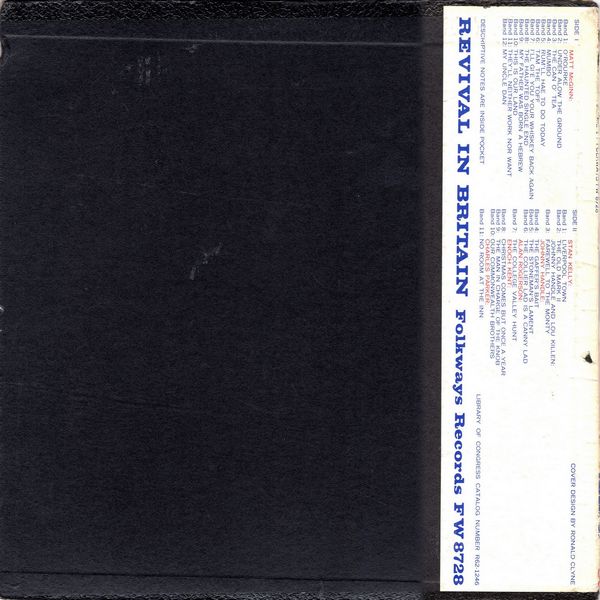

BRITISH FOLKSONG REVIVAL

sung by Mattt McGinn, Alan Rogerson, Enoch Kent, Johnny Handle, Stan Kelly, Charles Parker

(in which are presented some of the new writers who have appeared on the scene of the British Folksong Revival.)

The British popular revival of interest in folk-music dates roughly from 1950. Prior to that date there existed the English Folk Dance and Song Society but this organization was more concerned with the collect ing and preservation of folksongs than with their popularization. Their existed also a handful of enthusiasts scattered throughout the country and it is to them that the popular revival owes most of its direction and encouragement. A good deal of this direction has been exerted through the media of BBC radio programmes and the occasional television series

The skiffle movement, which in 1953 burst onto the British musical scene with explosive violence, marked the first stage of the popular revival and it was during that period that the basic of the 'folk club' idea was laid. The musical diet of the skiffle movement was, at first, exclusively American and, to a large extent, limited to the songs of Leadbelly and Guthrie. Later, Scots and English songs began to filter into the skiffle repertoire but only after they had undergone considerable rhythmical adaptation and had been translated into the Anglo-American idiom. To hear the 'Barnyards of Delgaty1 sung by young cocknies in the carefully acquired accents of Arkansas and Brooklyn was an experience, that none of us who were fortunate enough to be on the scene during that period will easily forget.

The skiffle movement was not an isolated phenomenon but a stage of the folk revival and its decline coincided with the growth of the urban folk clubs.

At first the clubs differed little from their skiffle forebears, the accent was still predominantly trans-Atlantic, the repertoire, though somewhat extended, was still American, as was the prevailing guitar-type accompaniment. The only notable change was one of emphasis, for whereas skiffle had relied on the ensemble performance, the folk clubs tended to rely on the solo, self-accompanied singer.

Changes were, however, taking place and by 1956 an increasingly large number of new young singers were turning to the domestic repertoire. The majority of them, it is true, were imitators of established British singers rather than performers in their own right, but they were, nevertheless, beginning to grapple valiantly with the English, Scots and Irish repertory and, more important, they were beginning to explore the mysteries of native singing styles.

Not all the young singers who were attracted to the folk revival in that period have continued to follow their original path, some have found it simpler to revert to the hybrid skiffle-folk style of the immediate past, others have found their way into those border regions where 'pop' and folk music carry on a somewhat embarrassing courtship. In spite of everything, a surprisingly large number have managed to come to terms with the traditional material without reducing it to the level of cute slop. That number is constantly growing and the newest recruits appear to have no difficulty whatsoever in accepting their traditional music. As recently as five years ago any young singer able to sing a traditional ballad was considered something of a freak; today they are as common as were Leadbelly imitators in the mid-fifties.

The change in repertoire has been accompanied by a change in singing style, the synthetic-American accents of the days of skiffle are now definitely passe; they are still heard in some of the clubs but the more discriminating members of the new generation of folksong enthusiasts tend to regard them as 'squares'. Another important change which has taken place during the last two or three years is the matter of accompaniments; some of the most talented among the revival singers have begun to abandon the guitar as an accompanying instrument and have turned to the concertina, melodeon and fiddle, while still others have returned to the indigenous unaccompanied singing style.

On the purely creative side, the development of the revival has been no less spectacular. New songs and new writers have been forthcoming at every stage of progress.

At first, as was to be expected, the new 'folksongs' were, with a few notable exceptions, either parodies of American folksongs and blues or, alternatively, songs and ballads conceived (for skiffle performance) in the Guthrie pattern. The second stage produced a number of songs patterned on the Irish come-all-ye's. These for the most part were uneasily self-conscious pieces, mechanical in form and didactic in intention. The stimulus which gave impetus to their production was the desire to prove that the new 'folksongs', like the old ones, were true reflections of the contemporary scene. Almost without exception, the themes of the songs of this period appear to have been chosen exclusively on the basis of their topicality rather than as a result of a deep human response to events or ideas. They deal with disasters like the aeroplane crash in which several members of an English football team met their deaths, with the fire at Smithfield market where a number of firemen died in the course of their duty, with the 'good stories' of the popular press. There is, of course, no reason, why such 'good stories' should not provide the raw material for good songs. In this case they did not, the competent journalism of the newspapers was reduced to doggerel verse and the whole effect was one of bathos.

Scores of new songs have made their appearance since then, their themes cover a wide range of human activities and concepts. Love, death, politics, capital punishment, "the bomb", nationalist aspirations, economic conditions, religious attitudes and ideas, etc., are subjects dear to the hearts of the new generation of "makers". It would seem that the best songs being made are the work of authors who can best be described as 'committed' men and women — committed in the sense that they are conscious of their roles in contemporary society and identify themselves with a specific social, political or religious ideal.

The editors do not claim that this collection of 'songs of the emerging tradition* is a definitive one or that it covers the best work of all the best new writers. It is a personal choice and, like any personal choice, reflects the likes and the dislikes of the choosers. They do say, however, that everyone represented here is seriously involved in attempting to create an image which will be a truthful reflection of the time in which they live.

Peggy Seeger & Ewen MacColl

Writers Of The British Folksong Revival

Matt McGinn — Born 1928 in the Gallowgate district of Glasgow; father a labourer in the meat market, mother a gut-scraper, both parents of Irish descent.

MacGinn, one of nine children, was evacuated during the war to Newton-Mearns and returned to the Gallowgate during a peak period of juvenile delinquency." "The Gallowgate had always been a rough, tough district but now all Hell was let loose. There was very little real reason for us who lived in the Gallowgate to be respectful of authority. Of sixteen of us in my age group, nine of us were put into approved schools. I myself had two convictions for housebreaking. I was in the school for eighteen months … it was run by Catholic brothers. It didn't have a good effect on me. Most of us like a little respect of some kind and you're not given a great deal of respect in a place like that. I was very religious at the time and I prayed every night;

I prayed for my da (father), my ma … I prayed for everybody and I always finished up with a prayer for myself: God, get me out of this bloody place. God, however, didn't intervene before my time was up."

McGinn returned to the Gallowgate at the age of 14, and worked as a labourer in an iron foundry, as a messenger in a flower-shop, in a lemonade factory, in a soap works, in a banana warehouse, as a bartender in a railway refreshment-room, as a tailor's presser and as a building-labourer. At the age of 18 he was called-up to serve his period of military-service in the army.

During this period he began to study anarchist writers and, later, Darwin and Marx. He confesses to having spent the greater part of his military-service In the guard-room for various acts of insubordination. He was finally discharged on medical grounds and for the next six years worked at various jobs, navvying (pick-and-shovel work), working as a porter in a whiskey bond (warehouse):

"I worked there with a bloke called Big Charlie.

He was a labourer but he'd read a Hell of a lot.

I learned a lot from Charlie."

Round about this time McGinn got married and he and his wife moved into a single-end (a one-roomed house) in Rutherglen. McGinn dates his trade-union activities from this time. He worked as a labourer in various ship-yards but his brand of militant trade-unionism made him unpopular with his employers and he was constantly forced to change his job. While working as a machine-operator in an engineering shop he won a trade-union scholarship to Ruskin College, Oxford where he studied and took a degree in economics; he later enrolled at a teachers' training-college where he won his teaching diploma. He recalls his Oxford experiences with a great deal of pleasure but it is evident that the 'mother of universities' proved unequal to the task of taming this 'gallus chiel'. That he has benefited from the discipline of university training cannot be denied but it is the Gallowgate which provides the main stimulus for his muse. He has been writing stories and poems about the Gallowgate for the last ten years; his songwriting activities, however, only began some four years ago.

McGinn's songs fall into two categories: (a) songs written in the folk-idiom. (b) songs inspired by the Glasgow music-hall tradition. He appears to work with equal facility in both genres. The themes of his songs cover a wide range of subjects -racial intolerance, Scottish Nationalism, the 'bomb', economic struggles, etc., are all grist to MacGinn's mill but his favourite theme is the uncompromising class outlook of Glasgow working folk and it is in the songs which deal with this that McGinn is at his most brilliant. For one who has had little or no exposure to folk-music his ability to make traditional-sounding tunes is extraordinary while his knack of crystallising, in a single phrase, the social attitudes of a community is almost uncanny. His epic ballad of 'O'Rourke' was awarded first place in the recent National Song Writing Competition sponsored by Reynold's News, one of Britain's oldest Sunday newspapers. In the opinion of the editors of this album it is the most perfect song of its type to come out of the revival.

The humour and irony which run through all of McGinn's songs belong to the Gallowgate as does the smouldering anger which underlies them but the love, which serves as a base for the anger, belongs to McGinn. It is his contribution to the class and the place which formed him.

Alan Rogerson — Born Near Wooler, Northumberland., 1915. Parents, farmers. Rogerson, a sheep farmer, lives and works at Commonbum Farm in that part of Northumberland which was once termed 'the debatable land'. Like most fell farmers he is kept busy with his sheep and his border-collies but, once in a while, takes time off to visit the pub in Wooler where he will sometimes sing a couple of songs. His 'College Valley Hunt' is based on a Cumberland hunting song 'The Elterwater Hounds' and is a great improvement on the original.

Enoch Kent — Born 1912 in the City of Glasgow. Father, for many years, worked as a municipal tram-driver but now works in a Glasgow ship-yard. Enoch won a scholarship to the Glasgow Art School and there studied design. He began singing folk-songs when he was 19 years old. "Of course, I did a bit of singing before that but it was mostly rubbish that I sang. I only began singing seriously when I was 19."

Kent was 'discovered' during the skiffle period of the revival and was signed up by one of the main British recording companies. In the process of being groomed for the hit-parade, he discovered that he was expected to sing with a 'heavenly choir' and a 'front-line combo of six guitars'. "The money was good but the work was lousy," he says, "so I packed it in and came to London." He earns his living by working as a designer for an advertising-agency in London's West-end. In the evenings and at week-ends he can be found singing at one or another of the London folk-clubs. He is regarded as one of the best singers of the British revival and a magnificent repertoire of traditional ballads, country songs, Glasgow street songs and contemporary pieces which he himself writes.

Of his song-writing activities he says: "I just take the notion every so often." There is, however, nothing of the dilettante in his attitude to work for he is a careful craftsman and discards a good fifty-per-cent of the songs he writes. Like the majority of revival song-writers be is solidly anti-establishment. His most successful songs are those in which he gives full reign to his keenly-developed sense of satire. His humour is not the kind which produces belly-laughs, it is too savage for that, too loaded with the sense of outrage. He uses it with the same deadly effect that some of his fellow citizens achieve with a razor.

His songs, though nearly always 'topical', are never of the pastiche 'Come All Ye' type, they are carefully considered pieces and even his most light-hearted creations are built around a core of tough logic. In the opinion of the editors of this album he ranks as one of the three or four most important contemporary British songwriters.

Johnny Handle (Johnny Pandrich) — Born 1935 in Wallsend, Northumberland. Father a schoolmaster. From the time he was a child, Pandrich was fascinated by rocks and minerals and spent a good deal of his spare time 'prospecting' in Northumberland and on the Westmoreland fells. It was this odd preoccupation with "things that come out of the earth" that earned him the nickname of 'Panhandle'.

A formal education at a local grammar school did not succeed in blurring the edges of his geological dream. When faced, however, with the problems of earning a living, it soon became apparent to him that the labour market had few demands for prospectors, so he did the next best thing and went to work in the pit. After serving a period of training at a National Coal Board center he began his mining career as an apprentice at the North Wall-Bottle pit, and embarked on a course of study which was eventually to make him a fully qualified mining surveyor.

During this period he became interested in jazz and was soon playing guitar and piano in a small 'jazz combo' which toured miners' clubs in the Tyneside area. As a result of this excursion into the world of art his nickname lost its prefix and he became Johnny Handle (a pun on the name of the composer of oratorios).

His experiences in the pit made a profound impression on him and his original passion for geology was extended to include both the pits and the colliers who worked in them. It was not, however, until a copy of 'Come All Ye Bold Miners', A.L. Lloyd's collection of mining songs, came into his hands that he determined to become the bard of the Northumberland coalfield. With songs like "Farewell to the Monty" and "The Gaffer's Bait" he has made a brilliant start.

Handle is a pit-bard in the great tradition of Tommy Armstrong and George Ridley; like them he is fascinated by the coal-mining community and, again like them, uses the vocabulary of the colliers themselves. To acquire the dialect and vocabulary of the Northumbrian colliers is something which has called for a conscious effort on Handle's part, it was something that he could never have got at grammar school. Having mastered it he has made it the language of his creative life.

With the emergence of regionalist songwriters like Johnny Handle, the British folksong revival can be said to have entered a new and important phrase.

Stan Kelly — Born 1919 in the city of Liverpool. Father "the best plumber on Merseyside". Attended a local council school until evacuated to Cheshire in 1940 … "which we stuck for only six weeks". The family returned to Liverpool in time to be bombed out of their home in one of the first Luftwaffe raids on Merseyside.

In 1942, Kelly won a scholarship to a grammar school and after studying there for five years won a further scholarship, this time to Cambridge University. His entry into the halls of higher learning was, however, delayed for two years by the military authorities who staked a priority claim on his services. His induction into H.M. Army was not without compensations and when the young warrior received his first week's wage of eleven shillings, he celebrated by getting married.

In the course of time he left the army and proceeded to Cambridge where, for the next five years, he studied mathematics and did research in electronic computers. Leaving Cambridge with a degree, a wife and four children, he began earning a living by consulting, planning and selling data processing systems.

Although he had always been fairly interested in folksongs, it was not until the period of his Cambridge sojourn that he became seriously involved. During that time he helped to found the St. Lawrence Folksong Society, organized a university skiffle group and began writing songs.

The main musical influences which inform his songwriting activities are (a) Anglo-Irish rebel songs and Come-all-ye's; (b) those 19th-century sailors' songs which have, of late, come to be inaccurately called 'Liverpool material'. when the Come-all-ye influence is uppermost, Kelly is led inevitably into the cul-de-sac of parody, that area where anger becomes flabby and satire is turned into burlesque. With the 'forebitter'-inspired songs, on the other hand, one is conscious of the fact that the author is making a real attempt to communicate his thoughts and feelings about 'his city'. The attempt is not always successful, often because the author, in trying to recapture his pre-Cambridge vision of Merseyside, allows his imagination to overshoot the mark with the consequence that he evokes a Merseyside which ceased to exist after 1920. When the attempt is successful, however, and the aim just right, the effect is very good indeed.

Charles Parker — Born 1919 in Bournemouth, a resort town on England's south coast. Father a railway-traffic clerk who later sold kerosene from a handcart on the Bournemouth streets. After a period spent at a secondary school, Parker entered a government laboratory as a would-be metallurgical research worker, but two years' application to this work finally convinced him of his unshakeably unscientific bent. During the war he served in the Royal Navy as a submarine commander and won the Distinguished Service Cross. After the war he entered Queens College, Cambridge, on a government ex-service grant and there studied history. In 1948, he joined the BBC as a feature-writer/producer, first in the European Service, then in the North American section of the Overseas Service. In 1954, he became senior feature producer of the Midland Region of the BBC. In 1958, he began, with Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger, to develop the actuality-radio-ballad and the success of works like "The Ballad of John Axon", "Song of a Road", "Singing the Fishing", and "The Big Hewer" have been largely responsible for shifting the emphasis from the interpretative to the creative aspects of the folkmusic revival in Britain.

Parker, who is a profoundly religious man, is deeply concerned with the rootlessness of modern urban life and is constantly preoccupied with the search for weapons with which to combat this. He believes that in the common search for weapons with which to combat this. He believes that in the common people there is to be found a great reserve of creative power the most vigorous expression of which is to be found in folk music and folk utterance. "No Room at the Inn" was written for a Nativity play which he composed and produced in his parish church in 1960.

Notes on the Songs

O'Rourke — In the early days of Time-and Motion-Study, a number of employers went to the length of having timing gadgets fitted to the doors of factory toilets. This attempt to play Canute to natural functions was not popular with the workers and their response to it was often unorthodox.

Under Alow The Ground — During the period when coal production was a decisive factor in Britain's war-effort, young men were given the choice of entering the coal-mining industry or the fighting service. The hero of this fine song chose the mines and lived to regret it.

The Can O' Tea — It has long been the practice for Britain's workers to interrupt their labours with a ten-minute morning-and-afternoon tea-break. Among the white-collar workers 'the break' is written into the charter of employment but for most manual workers it is something to be surreptitiously enjoyed. Employers generally turn a blind eye to the practice but, on occasion, use it as an excuse to fire a troublesome worker. In the winter of 196l, workers in a number of industries struck to legitimatize the tea break.

Mumbo — The hero of this song was a student friend of the author's Oxford days who was denied entrance to an English 'pub'.

Rum'll Hae To Do Today — McGinn, like most Scotsmen, is 'fond of a glass' and this excellent drinking song bears testimony to his fondness.

Tam The Toff — The Glasgow working-class have a heart dislike of those who pose as their 'betters'. With them the word 'toff' has a somewhat contemptuous ring. McGinn wrote this piece for his children.

I'll Gi'e You Your Whiskey Back Again — The Scots sabbath with its closed hostelries is, perhaps the most depressing feature of the Caledonian scene; for the 'hung-over' it is a form of torture. The hero of this song is a composite picture of all those poor souls who have wandered through interminable sabbaths with their tongues hanging out.

The Haunted Single-End — In the summer of 1961 Scottish newspapers carried the story of a Glasgow family who were so bothered by the attentions of a ghost that they were forced to vacate their apartment.

My Father Was Born A Hebrew — Fascists in West-Germany celebrated the Christmas season of 1960 by defacing the walls of synagogues and Jewish cemetories. It was these activities which prompted MacGinn to write this song.

This Is Our Land — The presence of American atomic-submarines in Scotland's Holy-Loch has been the object of much popular resentment. More than a score of songs, most of them fiercely nationalistic, have been born out of this situation. The piece given here is based upon a mawkishly patriotic parlour-ballad.

They'll Neither Work Nor Want — The catch-phrase which forms the burden of this witty song is one which, in Scotland, is usually applied to work-shy members of the lumpenproletariat. McGinn neatly turns the tables by making it fit the representatives of the so called 'upper-class'. The reference to the English Royal Family in verse 3 is calculated to endear the song to all Scots' republicans.

My Uncle Dan — McGinn's uncle Dan disgraced the family by becoming a foreman but Matt's song has done much towards removing this blot on the family escutcheon.

Liverpool Town — This somewhat raffish exercise in the style of a 'forebitter' is one of the authour's most successful songs.

The Old Mark II — The enlisted man undergoing his period of national-service is subject to many trials and tribulations, not least of which is his reluctant possession of a rifle which appears to have been issued to him with the express purpose of making his life intolerable. Stan Kelly's valedictory salute to the soldier's instrument of torture is one that will find an immediate echo in the hearts of all who have ever exchanged their names for numbers.

Farewell To The Monty — When the British coal mines were nationalized in 1945, the nationalization authority inherited many pits that were worked out. In the streamlining process which has gone on during the last few years it has sometimes been found necessary to abandon uneconomical pits. The Montague, or 'Monty', is one such pit. Handle's text combined with Lou Killen's beautiful tune, makes an extremely moving lament.

The Gaffer's Bait — The food which a collier takes down the pit is regarded as sacred; it is not only his most important link with the outside world and home but, in times of pit disaster, may be his link with life itself.

The Stoneman's Lament — This admirable description of a stoneman's working day is worthy of inclusion in any collection of coal-mining songs.

The Collier Lad Is A Canny Lad — The majority of Handle's songs are modelled upon the work of Tyneside Music-Hall writers such as Thomas Armstrong and George Ridley; The Collier Lad, however, is much closer, in idiom, to traditional Tyneside songs.

The College Valley Hunt — In the North of England, particularly in the English border counties of Cumberland, Westmoreland and Northumberland, fox-hunting is a sport of hardworking farmers, quarrymen, gypsum miners and the like. It is fox-hunters such as these, rather than the county gentry of the southern and midland counties, who have produced the best of Britain's hunting songs. Alan Rogerson's spirited piece is in the great tradition that produced 'John Peel'.

Christmas Comes But Once A Year — Kent is one of the few song-writers working in Britain today who can write a parody without it sounding like an undergraduate joke. To take a sugar-coated 'pop' of yesteryear and give it guts and a spine is no mean task but it is well within the range of Kent's sardonic talent.

The Man In Charge Of The Knob — During the season of goodwill, Christmas 1961, British TV audiences were given a glimpse of American neuclear preparedness via a short documentary dealing with the lads and lasses 'who keep a watchful eye on the free peoples of the world'. That short film provided the inspiration for this song.

Our Commonwealth Brothers — The British Tory Governments decision to restrict immigration from Commonwealth countries has shocked millions of people throughout the world. Kent's song was written on the eve of the government debate on the new act.

No Room At The Inn — Most of Parker's songs axe written as narration for radio programmes or as part of church performances. This one featured in a nativity play which he wrote for the Harborn parish church in 1960.