|

|

|

| more images |

Sleeve Notes

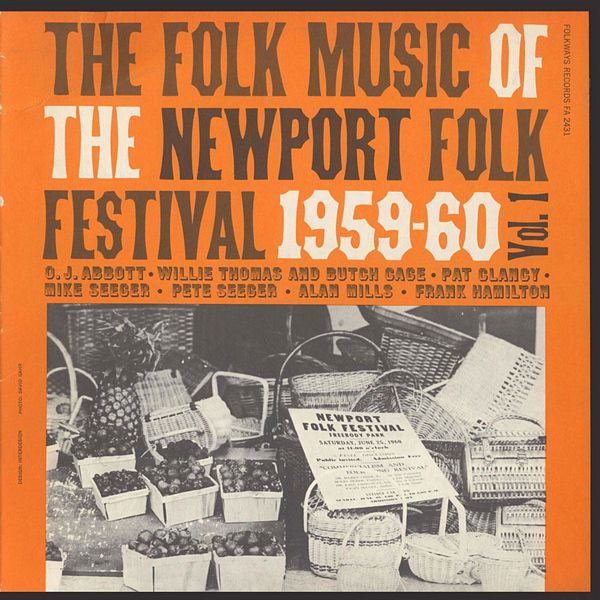

The Folk Music of The Newport Folk Festival: 1959-1960

by Irwin Silber

The city of Newport in Rhode Island has become the site, in recent years, for a vast conclave of jazz aficionados. Once the private sporting grounds for American millionaires and visiting royalty, Newport has become a name of international renown as the result of its annual Newport Jazz Festival, (In the summer of 1960, Newport's fame was transformed into notoriety — the result of a clash between local police and overenthusiastic college youngsters unable to purchase tickets to the sold-out concert.)

Enthused over their success, the Directors of the Newport Jazz Festival (incorporated as a nonprofit group) sometime early in 1959 decided to try their hands at an annual Folk Festival. In the early summer of 1959, and again in 1960, the First and Second Annual Newport Folk Festivals were presented at Freebody Park. As of this writing, with the future of the Newport Jazz Festival in doubt, there are no plans for any future Folk Festivals at Newport.

Both Festivals, of course, were recorded on tape from beginning to end. After the 1959 program, Vanguard issued a three-record album of highlights of the Festival. From the 1960 Festival, Vanguard issued another pair of discs and Elektra Records issued an LP of various Elektra recording artists at Newport. And now Folkways is releasing two records of "The Folk Music at The Newport Folk Festival."

Having attended both Festivals and listened to all of the recordings issued, I confess that I now despair that any but those who actually sat through all those hours in the wind and rain (1959) and cool breezes (1960) of the two Newport Folk Festivals will ever know what happened on those two weekends. This, of course, is not the fault well be called "The Crowd-Pleasers" of Newport, for the able editors there have carefully culled the tapes for those performances which won the greatest audience response. (They were limited, of course, by the fact that some of the most popular performing artists were under exclusive contract to other record companies. Thus, the Kingston Trio, the Brothers Four, Sabicas, The Gateway Singers and others, many of them show-stoppers, do not appear on any of these recordings.)

Elektra's version of the Newport Folk Festival 1960 consists of Theodore Bikel, Oscar Brand, Will Holt, and the Oranim Zabar Israeli Troupe.

After eliminating from the tapes the Vanguard selections, the Elektra exclusives, and the non-recordable artists of other labels, Moses Asch of Folkways went through what might be called "The Rest of Newport" and has put together a fascinating set of records. It too, of course, is not representative of the Newport Folk Festival in its entirety. But there is a thread running through these two discs which Moses Asch has pursued with the doggedness of a bloodhound. The thread is folk music, and while there was not too much of it at the Newport Folk Festivals, it appears in abundance on these two recordings.

The first side of this set (FA 2431-A) is devoted to folk singing. 0. J. Abbott, whose performance at the Festival was one of the high moments of drama for me, is a genuine folk singer who learned his ballads in the oral tradition. In his seventies, Abbott has a strong, clear voice and his songs are as moving as truth. "On The Banks of the Don" and "John Barleycorn" are both rich in folk humor, that wry Anglo-Saxon understatement which grows with repeated listening.

Willie Thomas and Butch Cage, two louisiana Negro blues singers, were brought to the Festival by folklorist Harry Oster. That their old country blues were lost in the vast arena of Freebody Park is, of course, no reflection on their art. They were in the wrong place at the wrong time — vainly trying to communicate to an audience that had no basis for understanding their music. Thomas and Cage are, quite obviously "primitives." An age of slick arrangements are amplified instruments has left them behind. There axe only a few places in the South today where an old-time blues fiddle can still be heard. The title of their first song, "I'm A Stranger Here," sums it up best.

Patrick Clancy, not so many years off the boat from Ireland, is keeping alive the wonderful tradition of Irish folk music. His unaccompanied rendition of the haunting Napoleonic ballad, "Bonnie Bunch O' Roses-O' is left over from the 1959 Festival — and a gem it is!

Mike Seeger winds up the first side of this set. Mike, if not a singer directly from the folk tradition. His songs and singing style are all second hand. But he has learned his songs and his style from folk singers — and he believes in keeping their tradition alive. His rendition of this American descendant of one of the great old British Ballads (Child #295) is a fine example of the ballad tradition. If there are some who feel that a point has been stretched by placing this cut with the authentic folk singing, they may view this selection as the best possible transition to Side Two.

Side Two of this set (FA 2431-B) is a fine representation of the current trend to keeping alive the authentic traditions of folk song by singers who are not themselves of the folk. Pete Seeger, a member of one of America's most illustrious musicological families, has earned a well-deserved reputation for devotion to the beauties of folk music and the ability to communicate the underlying emotional excitement of the folk heritage. In this song, "Cumberland Mountain Bear Chase," one catches a glimmer of the boundless enthusiasm and artistic sympathy which Pete Seeger brings to folk music.

To 17 million people north of the United States, Alan Mills is the voice of Canadian folk music. A trained singer with a deep, rich voice, Mills has devoted himself to the folk heritage of Canada. As performer, as editor, as radio and television personality, as song-writer, Mills' constant theme is Canadians. His interests and repertoire include both French and English songs of Canada and it is safe to say that no one has become more identified in the public mind with Canadian folk song than Alan Mills.

Frank Hamilton is the kind of creative musician whom other folk singers flock to listen to whenever the opportunity arises. His remarkable musical gifts, frequently on display at The Gate of Horn in Chicago, have almost gone unrecorded. (One LP, Folkways' "Nonesuch" — FA 2439, recorded with Pete Seeger, is a dazzling display of instrumental pyrotechnics on folk themes.) It is interesting to compare Frank Hamilton's version of "I'm A Stranger Here" with the one performed by Willie Thomas and Butch Cage. Aside from a similarity in theme and the same title, the two songs are completely different — and yet, they had a common origin.

Side Three in this set (FA 2432-A) might be subtitled "The South." Here are three distinct but related folk music traditions — all with their roots in that great storehouse of folk expression, the American South.

In their two songs, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry represent the work song and blues tradition of the Southern Negro. Themselves decades removed from the origin of these songs, McGhee and Terry still retain bonds of musical empathy and understanding with their roots. By a strange quirk of recording techniques at "live" programs, we have had preserved for us a most unusual recording of the famous Negro prisoner's song, "Midnight Special." What we hear "on mike" is Brownie McGhee's harmony with Sonny Terry's melody in the background. Students of "Folk harmony" should find this particularly instructive.

The New Lost City Ramblers, whose musical love affair with their own particular brand of old-time music has been going on some four or five years now, have been responsible for a remarkable revolution in the style and content of city folksinging. The Ramblers — Mike Seeger, John Cohen and Tom Paley — found that they had a common interest in the Southern commercially recorded folk music of the 1920's and early 1930's. It is a music peculiarly transitionary in character. In the period shortly after World War I, a combination of economic pressures and population growth plus the impact of expanding 20th Century civilization produced a remarkable migration in in the South. Families of hill folk whose ancestors had settled in the mountains of the western Carolinas, eastern Tennessee and Kentucky, West Virginia, etc. began to pour forth from the mountains, seeking a new way of life and ready cash in the new factories and mills of the South.

As they came down from the hills, they fought with them a rich heritage of traditional song and a wonderful gift for music-making. Many of their ballads dated back more than 200 years. Others had been preserved from memories of Civil War days and fragments of popular songs which had slipped into the mountains. With the impact of a different kind of living, the songs began to change — taking on those characteristics which the performers and record companies considered more "commercial."

From these roots developed "hillbilly" music, the music or The Carter Family and Jimmy Rodgers, and contemporary "Bluegrass." (Less directly, and as a result of the impact of Negro music, it also contributed to modern-day rock-and-roll.)

The music of this transition period then vanished — preserved only on some Library of Congress discs the old 78 rpm records, most of them rare collectors' items. The New Lost City Ramblers discovered (or re-discovered) this music and have popularized it throughout the country among city folk-singers who have taken it to their hearts (and guitars) with a marvelous enthusiasm.

Frank Warner is southern-born himself, first seeing the light of this world in 1903 in Selma, Alabama. Grown and raised in the South, Frank has devoted himself for many years to developing intimate relationships with various folk-singers. He has made good friends and learned many fine songs — and he has set out to preserve these songs as close to the way he learned them as possible. The result may be heard on these three selections.

Side Four (FA 2432-B) is a small sampling of recent trends in the singing of folk songs. Fleming Brown, a talented young folk singer from Chicago, is much caught up in folk styles and is manfully trying to establish an individual expression with the context of authentic tradition.

John Greenway is the college professor turned semi-professional guitar-picker. Greenway, unlike most of the other performers in these recordings, comes to folk music from the academic side of the tracks. His book, "American Folksongs of Protest," is an important and useful study of a much-neglected area of folk music tradition. A great admirer of Woody Guthrie, Greenway frequently performs Woody's songs. "Talking Dust Bowl," one of Woody's greatest from the Dust Bowl era, is Greenway's selection here. I believe that the academic background is strikingly evident.

Guy Carawan is the city folk-singer turned crusader. Over the past few years, Carawan has devoted himself to singing on behalf of the movement for integration in the South. He has performed for sit-in demonstrations, integration rallies, etc. throughout the South. Here he sings what has become the theme song of the Negro movement in the south, "We Shall Overcome."

This then is "The Folk Music of the Newport Folk Festival." It is a far cry from the total programmatic impact of those two folk-singing weekends. But on these two discs you will find reflected, in microcosm, most of the significant elements of the American folk song scene today.

Irwin Silber is the editor of SING OUT magazine. He also edited the official program for the 1960 Newport Folk Festival.